Results for “piketty” 176 found

“We all know that wealth inequality has gone up”

That is a response to the Piketty criticisms from Paul Krugman, and also mentioned by Matt Yglesias. Phiip Pilkington also has a useful treatment. This point however doesn’t do the trick as a defense. Keep in mind that the “new and improved numbers,” as produced by Chris Giles, are showing doubts about the course of measured wealth inequality in the UK. Maybe wealth inequality hasn’t gone up.

Now maybe that does “have to be wrong.” But if the “new and improved” numbers are wrong, it is hard to then argue Piketty’s wealth inequality numbers can be trusted. In which case we are back to knowing that income inequality has gone up, but not knowing so much concrete about wealth inequality. (That is one reason why my own Average is Over focuses on income, and on labor income in particular, because that is where the main action has been.) The data section of Piketty’s book, which has gathered so much praise, then is not so useful, though by no fault of Piketty’s. We might think it likely that wealth inequality has gone up, but if we are going to do these selective overrides of the best available data, we cannot trust the data so much period or otherwise cite it with authority. We also could not map wealth inequality into particular measures of the r vs. g gap at various periods of time.

If there is one big lesson of the FT/Piketty dust-up, it is that we don’t have reliable numbers on wealth inequality.

Now do we in fact “know” that wealth inequality has gone up? See this piece by Allison Schrager. Intuitions about wealth vs. income inequality are trickier than you might think. And on what we actually do and do not know, here is a very good comment on Mian and Sufi’s blog (for U.S. data):

Assorted links

1. The fox and the hedgehog, literally.

2. Are today’s teenagers the best-behaved of all time?

3. Gordon Tullock on the economics of slavery.

4. James Hamilton on Piketty (self-recommending).

5. The gadget that makes sure you never lose anything again (there is no great stagnation, perhaps this time for real).

The inequality that matters

Brenda Cronin reports:

Recent hand-wringing about income inequality has focused on the gap between the top 1% and everyone else. A new paper argues that the more telling inequities exist among the 99%, primarily driven by education.

“The single-minded focus on the top 1% can be counterproductive given that the changes to the other 99% have been more economically significant,” says David Autor, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist and author of the study.

His paper, “Skills, Education and the Rise of Earnings Inequality Among the ‘Other 99 Percent’,” comes as something of riposte to French economist Thomas Piketty, whose bestselling “Capital in the 21st Century” has ignited sales and conversation around the world with its historical look at the fortunes of the top 1%.

Mr. Autor estimates that since the early 1980s, the earnings gap between workers with a high school degree and those with a college education has become four times greater than the shift in income during the same period to the very top from the 99%.

Between 1979 and 2012, the gap in median annual earnings between households of high-school educated workers and households with college-educated ones expanded from $30,298 to $58,249, or by roughly $28,000, Mr. Autor says. During the same period, he argues, 99% of households would have gained about $7,000 each, had they realized the amount of income that shifted during that time to the top 1%.

There is more here, including good graphs.

Assorted links

1. Will you hire someone to do your grocery shopping for you?

2. New DSGE blog.

3. The Philadelphia Eagles are now targeting college graduates. Educational signaling comes to NFL football.

4. Can conservatives be funny?

5. Bill Gates on Jeffrey Sachs.

The other new French book on inequality

It is The Society of Equals, by , and it is a transatlantic look at how the notion of inequality has changed over the last three centuries. It strikes me as the sort of book Crooked Timber would have a symposium on. Here is one good bit:

Thus there is a global rejection of society as it presently exists together with acceptance of the mechanisms that produce that society. De facto inequalities are rejected, but the mechanisms that generate inequality in general are implicitly recognized. I propose to call this situation, in which people deplore in general what they consent to in particular, the Bossuet paradox. This paradox is the source of our contemporary schizophrenia. It is not simply the result of a guilty error but has an epistemological dimension. When we condemn global situations, we look at objective social facts, but we tend to relate particular situations to individual behaviors and choices. The paradox is also related to the fact that moral and social judgments are based on the most visible and extreme situation (such as the gap between rich and poor), into which individuals project themselves abstract, whereas their personal behavior is concretely determined by narrower forms of justification.

Roger Berkowitz has a very good review here, excerpt:

As does Piketty, Rosanvallon employs philosophy and history to characterize the return of inequality in the late 20th and now 21st centuries. And Rosanvallon, again like Piketty, worries about the return of inequality. But Rosanvallon, unlike Piketty, argues that we need to understand how inequality and equality now are different than they used to be. As a result, Rosanvallon is much more sanguine about economic inequality and optimistic about the possibilities for meaningful equality in the future.

And:

…inequality absent misery may not be the real problem of political justice. The reason so much inequality is greeted with resentment but acceptance, is that our current imagination of justice concerns visibility and singularity more than it does equality of income.

Recommended.

Assorted links

Assorted links

1. Martin Feldstein on Piketty. And Wojciech Kopczuk and Allison Schrager on wealth taxes. Piketty and survivorship bias.

2. Poland will institute biometric ATMs.

3. The new Peter Thiel book (self-recommending).

4. The record of Andrew Cuomo — worth a ponder.

5. Why don’t octopus arms stick together?

6. Is falling household consumption behind secular stagnation?

From the comments

Here is Brett on Piketty:

I’m surprised to see so few critiques of Piketty on the grounds that higher wealth and income inequality won’t necessarily lead to oligarchical politics and the capture of the economy by rentiers. I’m a bit skeptical myself of his interpretation of 19th century politics – at the same time we had the Belle Epoque, there was increasing working class political power in the UK (particularly with reforms in the 1830s and 1860s), the lead-up to the near-complete loss of political power in the House of Lords in 1911, the rise of income taxes in both the UK and France, greater social mobility, broader modernization and consumer culture, and so forth. You see some pushback from Larry Bartels and the like pointing to research showing policymaking following the preferences of the rich and organized, but they don’t provide much information about whether this has changed with increasing income and wealth inequality – the rich and organized interest groups may have just always had a disproportionate interest on policymaking, even during the Postwar Period.

Morgan Kelly, in his review (via John O’Brien), serves up a related point:

If Piketty’s story about slow growth leading inevitably to rising inequality and the power of the rich is true, then we expect that inequality would have risen sharply during the 19th century when growth in industrialised economies was less than 1 per cent per year. In fact the longstanding research of Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson on English inequality (which Piketty, incredibly, fails to cite) finds inequality was fairly constant, albeit high, until about 1870, and then appears to have fallen somewhat until 1913.

Wednesday assorted links

1. The new empirical economics of management.

2. Is entering adulthood in a recession linked to lower narcissism later in life? (speculative)

3. Talk of inequality is not a political winner for Democrats.

4. Felix Salmon’s inaugural money podcast for Slate, iTunes subscription here.

5. The robot car of tomorrow will be programmed to hit you.

The wisdom of Larry Summers

Already there are more American men on disability insurance than doing production work in manufacturing.

There is also this:

The determinants of levels of consumer spending have been much studied by macroeconomists. The general conclusion of the research is that an increase of $1 in wealth leads to an additional $.05 in spending. This is just enough to offset the accumulation of returns that is central to Piketty’s analysis.

That is from this very good Summers review of Piketty.

Assorted links

Two Surefire Solutions to Inequality

Here is a surefire solution to inequality–Increase fertility among the rich. If the rich had more children, capital would grow more slowly across the generations and perhaps not at all. If r=4 and g=2 then capital doubles as a share of the economy in 35 years (using the rule of 70). That figure is actually too low as it assumes that the wealthy save all of their capital income but let’s stick with 35 years and call that a generation. Wealth per rich person, however, only doubles if every wealthy family has just 2 children. If every wealthy family has 4 children, wealth per person doesn’t increase and so inequality does not increase even when r>g. If the wealthy consume about 20% of their capital income (still a very high savings rate) and have just 3 children then again we have approximate balance and no increase in inequality over the generations. With a more reasonable figure on r-g or with more children, wealth per person actually declines.

Thus, Piketty’s “patrimonial capital” contains its own internal contradiction. The more patrimony the less capital.

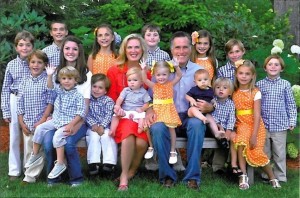

So how can we increase fertility among the rich? Mormon fertility is higher than average so capital inequality could decline if more rich people will be or become Mormons. Had we elected a President Romney (5 children and some 22 grandchildren! Or is it 23? Romney has lost count), perhaps that would have encouraged greater fertility among the rich.

So how can we increase fertility among the rich? Mormon fertility is higher than average so capital inequality could decline if more rich people will be or become Mormons. Had we elected a President Romney (5 children and some 22 grandchildren! Or is it 23? Romney has lost count), perhaps that would have encouraged greater fertility among the rich.

It’s an evolutionary puzzle why the rich don’t have more children as the costs to them are low and at very high levels of wealth there is no quantity-quality tradeoff. Perhaps this is a temporary response to the shock of birth control. If so, the effect of the shock is likely to fade over time as evolution works its logic.

In Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids Bryan Caplan notes that we overestimate the effect of parental investment on children and we underestimate the pleasures of grandchildren, in both cases choosing too few children. The rich should read Bryan’s book.

In these calculations I have assumed that primogeniture won’t make a comeback, that seems solid. Assortative mating, however, will slow wealth dispersion. I have also assumed that savings and fertility are independent which is unlikely to be the case. Becker and Barro (1988) suggest that more children will increase savings but less than proportionally so the logic continues to hold. Note also that this works both ways, wealthy people with fewer children will save less. Bill Gates has three children but has already given away a substantial fraction of his fortune and he has pledged to give away much more. Even parental altruism has its limits and Bill Gates has decided that on the margin he would rather give money to poor children in Africa than to his own children. Bill Gates’s shadow will not eat our future.

So what is the second surefire method to reduce capital inequality? Reduce fertility among the rich! If the rich as a class have fewer than 2 children then it follows inexorably that their time is numbered, albeit without first creating a small number of very rich people.

The logic of r-g turns out to be highly dependent on savings behavior, fertility decisions and the nature of altruistic bequests.

19th century inequality and the arts

Here is a well-written piece by Epicurean Dealmaker (ED) on the arts and economic inequality. Another response is here from Salon, also see the pieces that ED links to, such as Henry Farrell (and more here and Matt here). Unfortunately, ED cannot get beyond his preferred framing of the problem in terms of inequality and inequality alone. He has “inequality on the brain.”

Here is the nub of the critique:

Cowen takes a detour to praise the cultural dynamism and productivity of 19th Century France, which he claims results from the substantial socioeconomic inequality of the period. This is a pivot too far.

ED fails to note that:

1. Much of the artistic creativity of the 19th century stemmed from its wealth creation, not from its inequality per se. He specifies a setting where a robber baron stole from a working man, and supposes I am defending the theft by arguing it brought us some good art. That is an imaginary creation of ED. The very passage from me he cites refers to the virtues of wealth but does not refer to inequality.

2. For much of the latter three-quarters of the 19th century, consumption inequality appears to have declined. Oops.

3. Many of his intemperate statements about the history of art are wrong or doubtful or exaggerated and have been answered or at least contested, including in the five books I have written on the economics of the arts, including In Praise of Commercial Culture.

4. Let’s not talk about “the arts.” Reproducible and non-reproducible art forms will respond very differently to income inequality, as Alex and I argued in the SEJ. Cooking is yet another story, if we are going to call that art.

5. Piketty himself neglects the “wealth can generate additional TFP” possibility, and that remains a significant hole in his argument.

Overall this ED post is a good example of how easily and quickly one can go awry by an obsession with framing everything in terms of inequality. It also shows the drawbacks of a relative unfamiliarity with the basic literature, including for that matter the recent book by Piketty.

Assorted links

1. Data on blockbuster movies.

2. Can China use its capital in a time of crisis?

3. My Piketty NYT column from July: “If you’d like to know where American political debates are headed, the data suggest a simple answer. The next major struggle — in economic terms at least — will be over whether taxes on personal wealth should rise — and by how much.” I believe this was the first coverage of Piketty in a major media outlet.

4. The prices of Qatari license plates.

5. First Bay area sex truck (what does this imply about living quarters?)

Assorted links

1. Good interview with Michael Strain.

2. Raw data from Piketty, lots of it. And confronting the Texas police with Bayesian reasoning. And how Paul Krugman views his own endeavors.

3. When do men not want a pretty face? (speculative)

4. My 2005 post on whether or not we should tax capital. And the bad rentier?

5. Very good Edward Luce FT piece on Modi.

6. Andrew Gelman on Seth Roberts, great piece.

7. Al Roth predicts 98 years out (seems more like thirty years out to me, or even less).

I could not have said it better myself.