The time needed to fill jobs

You can see a tightening labor market, and some of this you might interpret in terms of a growing skills gap:

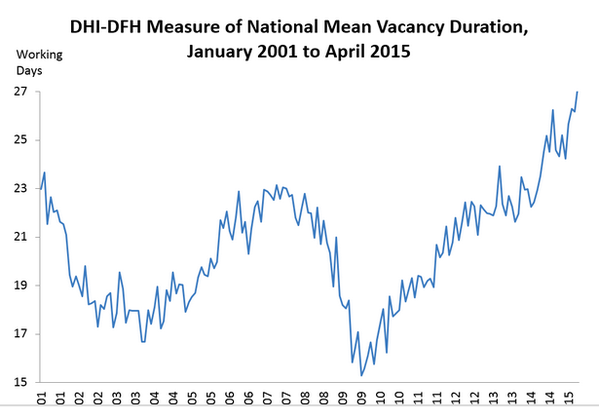

The national time-to-fill average rose in February to the highest level in 15 years.

Sponsored by the career sites publisher Dice Holdings, the Dice-DFH Vacancy Duration Measure says it took an average of 26.8 working days to fill jobs in February. In January, according to the report, the average (as revised) was 25.7 working days.

“We are continuing to see signs of a tightening labor market,” said Michael Durney, president and CEO of Dice Holdings. “Unemployment rates are declining across several core industries, such as tech and healthcare, and the time-to-fill-open positions has hit an all-time high in the 15 years the data has been tracked.”

Jobs in the financial services sector took the longest to fill, averaging 43.1 days. Healthcare jobs averaged 42.6 days to fill. Both are historic highs for their respective industry sectors.

The full article, by John Zappe, is here, via David Wessel.

By the way, the skills mismatch hypothesis (not a substitute for AD hypotheses, let me stress) is stronger than you think. Catherine Rampell writes:

Companies themselves are indeed reporting difficulty acquiring talent. Nearly half of small and medium-size businesses with recent vacancies say they could find few or no “qualified applicants,” according to the latest monthly survey of the National Federation of Independent Business. Over the past couple of years, firms have also become increasingly likely to say that “quality of labor” is the “single most important problem” facing their businesses.

I have generally been skeptical of the “skills mismatch” story, mostly because wage growth has been so pitiful during this recovery. If qualified applicants were really so scarce, businesses should be bidding up the salaries of the few hot commodities available. But Steven J. Davis , an economics professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and one of the creators of the vacancy duration metric, says it’s unclear how a widespread skills mismatch, if one exists, would actually affect wages. Maybe a shortage of some highly desirable skill would lead employers to bid up the price of that qualification, he says, but that same scarcity might also lead firms to instead settle “for workers who have less of [or] lower-quality versions of the desired skills.” That could, in theory, cause hourly wages to fall overall. Robust research on the connection between skills mismatch and wages is in short supply.

This point from Davis is appreciated only rarely.