Politically Incorrect Paper of the Day: The United Fruit Company was Good!

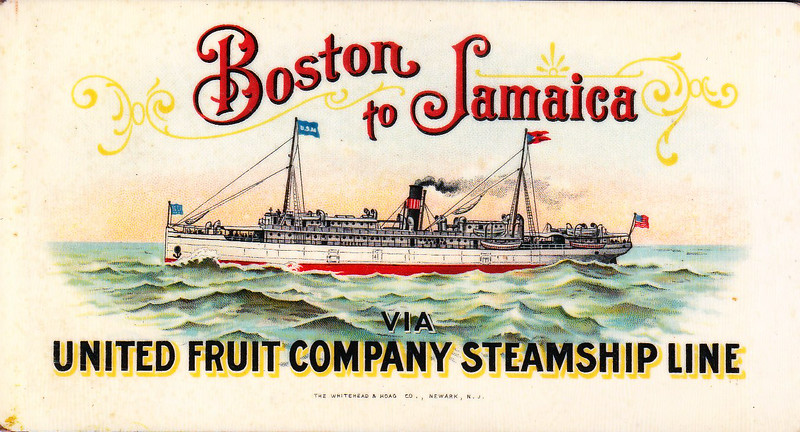

The United Fruit Company is the bogeyman of Latin America, the very apotheosis of neo-colonialism. And to be sure in the UFC history there is wrongdoing and plenty of fodder for conspiracy theories but the UFC also brought bananas (as export crop), tourism, and in many cases good governance to parts of Latin America. Much, however, depends on the institutional constraints within which the company operated. Esteban Mendez-Chacon and Diana Van Patten (on the job market) look at the UFC in Costa Rica.

The UFC needed to bring workers to remote locations and thus it invested heavily in worker welfare:

…the UFC invested in sanitation infrastructure, launched health programs, and provided medical attention to its employees. Infrastructure investments included pipes, drinking water systems, sewage system, street lighting, macadamized roads, a dike (Sanou and Quesada, 1998), and by 1942 the company operated three hospitals in the country.

… Given the remoteness the plantations and to reduce transportation costs, the UFC provided the majority of its workers with free housing within the company’s land. This was partially motivated by concerns with diseases like malaria and yellow fever, which spread easily if the population is constantly commuting from outside the plantation. By 1958 the majority of laborers lived in barracks-type structures… [which] exceeded the standards of many surrounding communities (Wiley, 2008).

The UFC wasn’t just interested in healthy workers, they also needed to attract workers with stable families:

The UFC wasn’t just interested in healthy workers, they also needed to attract workers with stable families:

… One of the services that the company provided within its camps was primary education to the children of its employees. The curriculum in the schools included vocational training and before the 1940s, was taught mostly in English. The emphasis on primary education was significant, and child labor became uncommon in the banana regions (Viales, 1998). By 1955, the company had constructed 62 primary schools within its landholdings in Costa Rica (May and Lasso, 1958). As shown in Figure 6a,spending per student in schools operated by the UFC was consistently higher than public spending in primary education between 1947 and 1963.21 On average, the company’s yearly spending was 23% higher than the government’s spending during this period.

…The UFC did not provide directly secondary education although offered some incentives. If the parents could afford the first two years of secondary education of their children in the United States, the UFC paid for the last two years and provided free transportation to and from the United States.

A key driver of UFC investment was that although the UFC was the sole employer within the regions in which it operated, it had to compete to obtain labor from other regions. Thus a 1925 UFC report writes:

We recommend a greater investment in corporate welfare beyond medical measures. An endeavor should be made to stabilize the population…we must not only build and maintain attractive and comfortable camps, but we must also provide measures for taking care of families of married men, by furnishing them with garden facilities, schools, and some forms of entertainment. In other words, we must take an interest in our people if we might hope to retain their services indefinitely.

This is exactly the dynamic which drove the provision of services and infrastructure in unjustly maligned US company towns. It’s also exactly what Rajagopalan and I found in the Indian company town of Jamshedpur, built by Jamshetji Nusserwanji Tata.

The UFC ended in Costa Rica in 1984 but the authors find that it had a long-term positive impact. Using historical records, the authors discover a plausibly randomly-determined boundary line between UFC and non-UFC areas and comparing living standards just inside and just outside the boundary they find that households within the boundary today have better housing, sanitary conditions, education and consumption than households just outside the boundary. Overall:

We find that the firm had a positive and persistent effect on living standards. Regions within the UFC were 26% less likely to be poor in 1973 than nearby counterfactual locations, with only 63% of the gap closing over the following 3 decades.

The paper has appendixes A-J. In one appendix (!), they show using satellite data that regions within the boundary are more luminous at night than those just outside the region. The collection of data is especially notable:

For a better understanding of living standards and investments during UFC’s tenure, we collected and digitized UFC reports with data on wages, number of employees, production, and investments in areas such as education, housing, and health from collections held by Cornell University, University of Kansas, and the Center for Central American Historical Studies. We also use annual reports from the Medical Department of the UFC describing the sanitation and health programs and spending per patient in company-run hospitals from 1912 to 1931. We also collected data from Costa Rican Statistic Yearbooks, which from 1907 to 1917 contain details on the number of patients and health expenses carried out by hospitals in Costa Rica, including the ones ran by the UFC. Export data was also collected from these yearbooks, and from Export Bulletins. 19 agricultural censuses taken between 1900 and 1984 provide information on land use, and we use data from Costa Rican censuses between 1864-1963 to analyze aggregated population patterns, such as migration before and during the UFC apogee, or the size and occupation of the country’s labor force.

Overall, a tremendous paper.