Category: History

It is time to back off from Greenland

I do hope it falls eventually into U.S. hands, as I explain in my latest Free Press piece. But now is not the time and furthermore that should happen voluntarily, not coercively. Here is an excerpt:

The better approach is to let the Greenlanders choose independence on their own. They may be ready to do so. In a survey last year, 56 percent of Greenlanders favored independence from Denmark, with just 28 percent opposed. This should not be a tremendous surprise. The Danes have not always treated Greenland well; the legacy of Denmark taking away the children of Greenlanders 75 years ago still remains—and similar issues crop up to this day.

If and when Greenlanders do choose independence, the U.S. should, when conditions feel right, make a generous offer to Greenland. If they do not take the offer, we might try again later on, but we should not intimidate or coerce them. We should respect their right of independence throughout the process. That would increase the likelihood that the future partnership will be a cooperative and fruitful one.

The courtship could take 20 or 30 years, but I am pretty sure that eventually Greenlanders will see the benefits of a stronger U.S. affiliation.

I do not think that simply trying to “buy” Greenland is going to work. I am reminded of my own fieldwork, roughly 20 years ago, in a small Mexican village in the state of Guerrero. General Motors wanted to buy most of the land in and around the village, for the purpose of building a racetrack to test GM cars. It had a lot of money to offer, and at the time a family of seven in the village might have earned no more than $1,500 a year. But the negotiations never got very far. The villagers felt they were not being respected, they did not trust the terms of any deal, and they feared their ways of life would change irrevocably. The promise of better roads, schools, and doctors—in addition to whatever payments they might have negotiated—simply fell flat.

These are very important issues, so we need to get them right.

The puzzle of Pakistan’s poverty?

Until 2009, India was poorer than Pakistan on a per capita basis. India truly became richer than Pakistan after 2009 and since then it hasn’t looked back. If trends continue for a decade, India will be more than twice as rich as Pakistan soon…

So why has India pulled ahead in GDP per capita? The reason is simple. Pakistan’s high fertility has driven population growth faster than India’s. In 1952 Pakistan had about one-tenth of India’s population; by 2025 it had grown to nearly one-seventh.

In other words, many of the added Pakistanis have not started working yet, but they are on the books to lower the per capita esstimate. There is much in this Rohit Shinde essay I disagree with, but it is a useful corrective to those who simply wish to sing “policy, policy, policy.” Putting aside its per capita lag, Pakistan has done a better job keeping up with India than you might think at first.

In any case, I am not predicting that trend will continue in the future, I do not think so. So someday this essay might look especially “off,” nonetheless it is worth a moment of ponder.

U.S. interventions in the New World, with leader removal

I can think of a few. I am not thinking of ongoing struggles, such as the funding of opposition to the Sandinistas, rather I wish to focus on cases where the key leaders actually were removed. After all, we know that is the case in Venezuela today. Maybe these efforts were rights violations, or unconstitutional, and yes that matters. But how did they fare in utilitarian terms?

Puerto Rico: 1898, a big success.

Mexican-American War: Removed Mexican leaders from what today is the American Southwest. Big utilitarian success, including for the many Mexicans who live there now.

Chile, and the coup against Allende: A utilitarian success, Chile is one of the wealthiest places in Latin America and a stable democracy today.

Grenada: Under Reagan, better than Marxism, not a huge success, but certainly an improvement.

Panama, under the first Bush, or for that matter much earlier to get the Canal built: Both times a big success.

Haiti, under Clinton, and also 1915-1934: Unclear what the counterfactuals should be, still this case has to be considered a terrible failure.

Cuba, 1906-1909: Unclear? Nor do I know enough to assess the counterfactual.

Dominican Republic, 1961-1954, starting with Trujillo. A success, as today the DR is one of the wealthiest countries in Latin America. But the positive developments took a long time.

I do not know enough about the U.S. occupation of the DR 1916-1924 to judge that instance. But not an obvious success?

Can we count the American Revolution itself? The Civil War? Both I would say were successes.

We played partial but perhaps non-decisive roles in regime changes in Ecuador 1963 and Brazil 1964, in any case I consider those results to be unclear. Maybe Nicaragua 1909-1933 counts here as well.

So the utilitarian in you, at least, should be happy about Venezuela, whether or not you should be happy on net.

You should note two things. First, the Latin interventions on the whole have gone much better than the Middle East interventions. Perhaps that is because the region has stronger ties to democracy, and also is closer to the United States, both geographically and culturally. Second, looking only at the successes, often they took a long time and/or were not exactly the exact kinds of successes the intervenors may have sought.

Absher, Grier, and Grier consider CIA activism in Latin America and find poor results. I think much of that is springing from cases where we failed to remove the actual leaders, such as Nicaragua and Cuba. Simply funding a conflict does seem to yield poor returns.

Why Some US Indian Reservations Prosper While Others Struggle

Our colleague Thomas Stratmann writes about the political economy of Indian reservations in his excellent Substack Rules and Results.

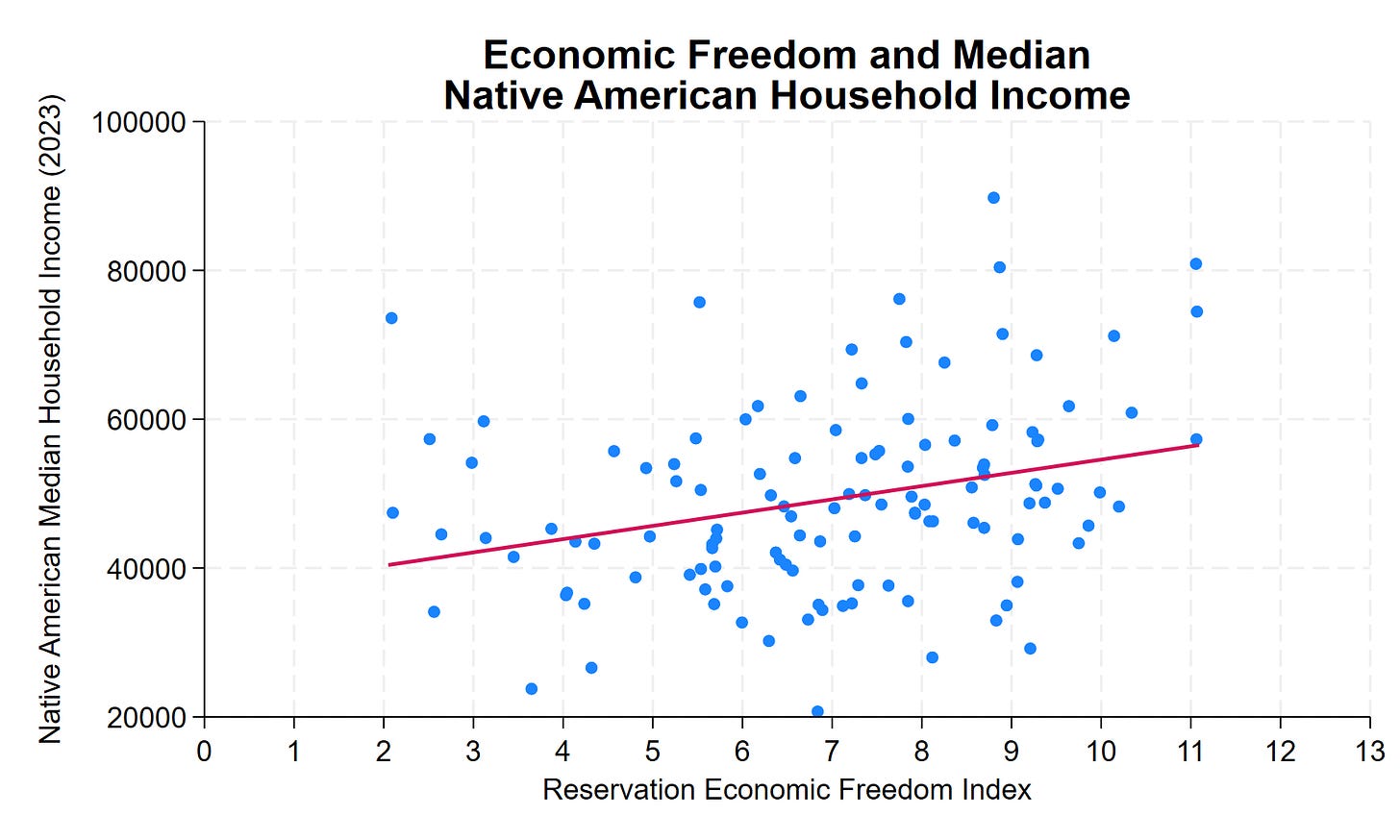

Across 123 tribal nations in the lower 48 states, median household income for Native American residents ranges from roughly $20,000 to over $130,000—a sixfold difference. Some reservations have household incomes comparable to middle-class America. Others face persistent poverty.

Why?

The common assumption: casino revenue. The data show otherwise. Gaming, natural resources, and location explain some variation. But they don’t explain most of it. What does? Institutional quality.

The Reservation Economic Freedom Index 2.0 measures how property rights, regulatory clarity, governance, and economic freedom vary across tribal nations. The correlation with prosperity is clear, consistent, and statistically significant. A 1-point improvement in REFI—on a 0-to-13 scale—correlates with approximately $1,800 higher median household income. A 10-point improvement? Nearly $18,000 more per household.

Many low-REFI features aren’t tribal choices—they’re federal impositions. Trust status prevents land from being used as collateral. Overlapping federal-state-tribal jurisdiction creates regulatory uncertainty. BIA approval requirements add months or years to routine transactions. Complex jurisdictional frameworks can deter investment when the rules governing business activity, dispute resolution, and enforcement remain unclear.

This is an important research program. In addition to potentially improving the lives of native Americans, the 123 tribal nations are a new and interesting dataset to study institutions.

See the post for more details amd discussion of causality. A longer paper is here.

What should I ask Henry Oliver?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with him. We will focus on our mutual readings of Shakespearer’s Measure for Measure, with Henry taking the lead. But I also will ask him about the value of literature, Jane Austen, Adam Smith, Bleak House, his book on late bloomers, and more.

Here is Henry’s (free) Substack. Here is Henry on Twitter.

So what should I ask him?

J. M. W. Turner, financial arbitrageur

Abstract. J. M. W. Turner is famous for his achievements in graphic arts. What is not known is that he engaged in some pioneering market arbitrage, a profitable and risk-free swapping of British government securities. His activities lead to interesting insights into British markets of the 19th century. Financial innovation frequently created profitable arbitrage opportunities. However, among regular investors it seems that it was mostly mavericks like Turner who took advantage of them. Apparently there were strong cultural factors that inhibited most people from imitating him, which allowed obvious pricing anomalies to persist for extended periods.

That is from a recent paper by Andrew Odlyzko. Via Colin.

What should I ask Kim Bowes?

Yes, I will be doing a Conversation with her. Here is Wikipedia:

Kimberly D. Bowes (born 1970) is an American archaeologist who is a professor of Classical Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. She specializes in archeology, material culture and economics of the Roman and the later Roman world. She was the Director of the American Academy in Rome from 2014–2017.[2] She is the author of three monographs…

While she is continuously focused on the archaeology and material culture of the Roman and later Roman worlds, her research interests have shifted from late antiquity and the archeologies of religion and elite space to historical economies with a distinct focus on poverty and the lived experience of the poor. Her forthcoming study on Roman peasants in Italy reflects a greater attention to non-elites in the studies of Roman archaeology and economic history and a shift in her methodology, integrating archaeological and scientific data, anthropological theory and historical economics become.

I am a big fan of her new book Surviving Rome: The Economic Lives of the Ninety Percent. So what should I ask her?

Three that Made a Revolution

Another excellent post from Samir Varma, this time on the 1991 reforms in India that launched India’s second freedom movement:

Three men you’ve probably never heard of—P.V. Narasimha Rao, Manmohan Singh, Montek Singh Ahluwalia—may be the three most important people of the late 20th century.

Bold claim. Audacious, even. Let me defend it.

Here are the numbers. In 1991, over 45% of Indians lived below the poverty line—roughly 400 million people. By 2024, extreme poverty in India had fallen to under 3%.

That’s 400 to 500 million people lifted out of poverty.

The largest democratic poverty alleviation in human history.

….So there they stood.

The precipice was visible. A Hindu politician from a dusty village in Telangana who spoke 17 languages and wrote novels nobody wanted to read. A Sikh economist from a village that no longer existed, who took cold showers at Cambridge and kept dried fruits in his pockets. Another Sikh economist who’d been the youngest division chief in World Bank history and wrote a memo that would change a country.

Three men. All products of a civilization that absorbs contradictions—that somehow fits Hindus and Sikhs and Muslims and Christians and Jains and Buddhists and Parsis into one impossibly diverse democracy. A civilization where, as I’ve written before, any statement you make is true, AS IS its opposite.

India was bankrupt. The gold was gone. The Soviet model they’d followed for forty years was collapsing in real time. Every assumption that had guided Indian economic policy since independence was being revealed as catastrophically wrong.

The intelligentsia still believed in socialism. The party cadres still worshipped Nehru’s memory. The opposition would scream about selling out to foreign powers. The bureaucracy would resist losing its control. The protected industries would fight to keep their monopolies.

But the three men had something their opponents didn’t: a plan. The M Document—the years of thinking—the technocratic expertise accumulated across decades. They had political cover—Rao’s tactical genius, his willingness to let Singh take the heat while he worked the back channels. They had credibility—Singh’s Cambridge pedigree, Ahluwalia’s World Bank experience, Rao’s decades of political survival.

And they had something else: the crisis itself. The one thing that could break through forty years of socialist inertia. The emergency that made the previously impossible suddenly necessary.

Varma tells the story well. For the full history consult the indispensable The 1991 Project, full of documents, oral histories and interviews.

Hat tip: Naveen Nvn.

*38 Londres Street*

The author is Philippe Sands and the subtitle is

So recommended, and added to my own list. And yes I did buy another book by Philippe Sands, the acid test of whether I really liked something.

Bring Back the Privateers!

Senator Mike Lee has a new bill that encourages the President to authorize letters of marque and reprisal against drug cartels:

The President of the United States is authorized and requested to commission, under officially issued letters of marque and reprisal, so many of privately armed and equipped persons and entities as, in the judgment of the President, the service may require, with suitable instructions to the leaders thereof, to employ all means reasonably necessary to seize outside the geographic boundaries of the United States and its territories the person and property of any individual who the President determines is a member of a cartel, a member of a cartel-linked organization, or a conspirator associated with a cartel or a cartel-linked organization, who is responsible for an act of aggression against the United States.

SECURITY BONDS.—No letter of marque and reprisal shall be issued by the President without requiring the posting of a security bond in such amount as the President shall determine is sufficient to ensure that the letter be executed according to the terms and conditions thereof.

My paper on privateers explains how privateers were historically very successful. During the War of 1812, roughly 500 privateers operated alongside a tiny U.S. Navy. The market responded swiftly—privateers like the Comet were commissioned within days of war’s declaration and began capturing prizes within weeks. Sophisticated institutional design combined combined profit incentives with regulatory constraints:

- Security bonds ensured compliance with license terms

- Detailed instructions protected neutral vessels and required civilized conduct

- Prize courts adjudicated captures and distinguished privateers from pirates

- Share-based compensation created good incentives for crews

- Markets emerged where crew could sell shares forward (with limits to maintain work incentives)

Privateers cost the government essentially nothing compared to building and maintaining a navy. Private investors financed vessels , bore the risks, and operated on profit-seeking principles. Moreover, privateers unlike Navy vessels had incentives to capture enemy ships, particularly merchant ships, not just blow them and their occupants out of the water. Of course, capturing the drugs isn’t very useful but it’s quite possible to go after the money on the return journey–privateers as hackers–which is just as good.

Here is my paper on privateering, here is the time I went bounty hunting in Baltimore, here is work on the closely related issue of whistleblowing rewards and here is the excellent historian Mark Knopfler on privateering:

*Central Asia*, by Adeeb Khalid

An excellent book, the best I know of on this region. Here is one bit:

The first printing press in Central Asia was established in Tashkent in 1870…

I had not understood how much Xinjiang (“East Turkestan”), prior to its absorption into newly communist China, fell under the sway of Soviet influence.

I had not known how much the central Asian republics had explicit “let’s slow down rural migration into the cities” policies during Soviet times.

The book is interesting throughout, recommended.

What should I ask Joanne Paul?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with her. From the Google internet:

Joanne Paul is a writer, broadcaster, consultant, and Honorary Senior Lecturer in Intellectual History at the University of Sussex. A BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinker, her research focuses on the intellectual and cultural history of the Renaissance and Early Modern periods…

She has a new book out Thomas More: A Life.

Here is her home page. Here is Joanne on Twitter. She has many videos on the Tudor period, some with over one million views.

So what should I ask her?

How harmful is the decline in long-form reading?

That is the theme of my latest Free Press column, here is one excerpt:

Oral culture, in contrast, tends to be more fluid, harder to evaluate and verify, more prone to rumor, and it has fewer gatekeepers. Those features have their advantages, as a good stand-up comedian will get louder laughs than a witty author. Or an explanation from YouTube, with moving visuals, may stick in our minds more than a turgid passage from a textbook. We also just love talking, and listening, as those modes of communication reach back into human history much further than reading and writing do. Speech is part of how we bond with each other. Still, if any gross generalization can be made, it is that oral culture makes objectivity and analytic thought harder to establish and maintain.

Given this background, both the good and the bad news is that the dominance of print culture has been in decline for a long time. Radio and cinema both became major communications media in the 1920s, and television spread in the 1950s. Those major technological advances have commanded the regular attention of billions, and still do so. Earlier in the 20th century, it suddenly became a question whether you take your ideas from a book or from the radio. And this was not always a welcome development, as Hitler’s radio speeches persuaded more Germans than did his poorly constructed, unreadable Mein Kampf.

The fact that books, newspapers, and reading still are so important reflects just how powerful print has been. How many other institutions can be in relative decline for over a hundred years, and still have such a hold over our hearts and minds?

The optimistic interpretation of our situation is that reading longer works has been in decline for a long time, and overall our civilization has managed the transition fairly well. Across history we have had various balances of written and oral cultures, and if some further rebalancing is required in the direction of the oral, we should be able to make that work, just as we have done in the past. The rise of television, whatever you may think of it, did not do us in.

A second and more pessimistic diagnosis is that print and reading culture has been hanging by a thread, and current and pending technological advances are about to give that thread its final cut. The intellectual and cultural apocalypse is near. Even if your family thinks of itself as well-educated, your kids will grow up unable to work their way through a classic novel. They will watch the Lord of the Rings movies, but never pick up the books. As a result, they are likely to have less scientific and analytic objectivity, and they will embody some of the worst and most volatile aspects of TikTok culture. They will, however, be able to sample large numbers of small bits of information, or sometimes misinformation, in a short period of time.

There is much more at the link.

Art as Data in Political History

From Valentine Figuroa of MIT:

Ongoing advances in machine learning are expanding opportunities to analyze large-scale visual data. In historical political economy, paintings from museums and private collections represent an untapped source of information. Before computational methods can be applied, however, it is essential to establish a framework for assessing what information paintings encode and under what assumptions it can be interpreted. This article develops such a framework, drawing on the enduring concerns of the traditional humanities. I describe three applications using a database of 25,000 European paintings from 1000CE to the First World War. Each application targets a distinct type of information conveyed in paintings (depicted content, communicative intent, and incidental information) and a cultural transformation of the early-modern period. The first revisits the notion of a European “civilizing process”—the internalization of stricter norms of behavior that occurred in tandem with the growth of state power—by examining whether paintings of meals show increasingly complex etiquette. The second analyzes portraits to study how political elites shaped their public image, highlighting a long-term shift from chivalric to more rational-bureaucratic representations of men. The third documents a long-term process of secularization, measured by the share of religious paintings, which began prior to the Reformation and accelerated afterward.

Here is the link, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Building a cohesive Indonesia

Building a cohesive nation-state amid deep ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity is a central challenge for many governments. This paper examines the process of nation building, drawing lessons from the remarkable experience of Indonesia over the past century. I discuss conceptual perspectives on nation building and review Indonesia’s historical nation-building trajectory. I then synthesize insights from four studies exploring distinct policy interventions in Indonesia—population resettlement, administrative unit proliferation, land reform, and mass schooling—to understand their effects on social cohesion and national integration. Together, these cases underscore the promise and pitfalls of nation-building efforts in diverse societies, offering guidance for future research and policymaking to support these endeavors in Indonesia and beyond.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Samuel Bazzi. As I have noted in the past, Indonesia remains a remarkably understudied and also undervisited country (Bali aside), so efforts in this direction should be appreciated.