AI and the FDA

Dean Ball has an excellent survey of the AI landscape and policy that includes this:

The speed of drug development will increase within a few years, and we will see headlines along the lines of “10 New Computationally Validated Drugs Discovered by One Company This Week,” probably toward the last quarter of the decade. But no American will feel those benefits, because the Food and Drug Administration’s approval backlog will be at record highs. A prominent, Silicon Valley-based pharmaceutical startup will threaten to move to a friendlier jurisdiction such as the United Arab Emirates, and they may in fact do it.

Eventually, I expect the FDA and other regulators to do something to break the logjam. It is likely to perceived as reckless by many, including virtually everyone in the opposite party of whomever holds the White House at the time it happens. What medicines you consume could take on a techno-political valence.

Agreed—but the nearer-term upside is repurposing. Once a drug has been FDA approved for one use, physicians can prescribe it for any use. New uses for old drugs are often discovered, so the off-label market is large. The key advantage of off-label prescribing is speed: a new use can be described in the medical literature and physicians can start applying that knowledge immediately, without the cost and delay of new FDA trials. When the RECOVERY trial provided evidence that an already-approved drug, dexamethasone, was effective against some stages of COVID, for example, physicians started prescribing it within hours. If dexamethasone had had to go through new FDA-efficacy trials a million people would likely have died in the interim. With thousands of already approved drugs there is a significant opportunity for AI to discover new uses for old drugs. Remember, every side-effect is potentially a main effect for a different condition.

On Ball’s main point, I agree: there is considerable room for AI-discovered drugs, and this will strain the current FDA system. The challenge is threefold.

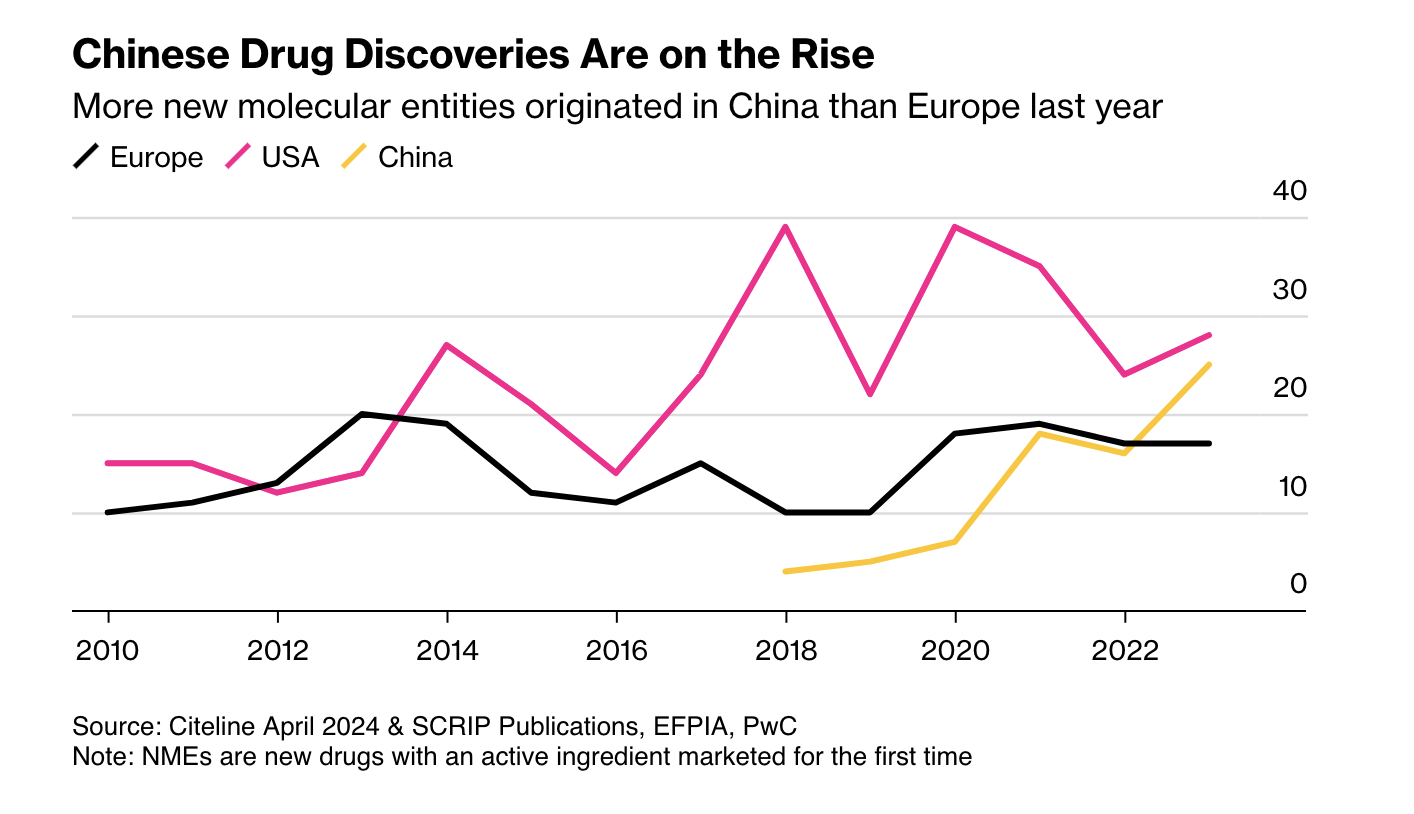

First, as Ball notes, more candidate drugs at lower cost means other regulators may become competitive with the FDA. China is the obvious case: it is now large and wealthy enough to be an independent market, and its regulators have streamlined approvals and improved clinical trials. More new drugs now emerge from China than from Europe.

Second, AI pushes us toward rational drug design. RCTs were a major advance, but they are in some sense primitive. Once a mechanic has diagnosed a problem, the mechanic doesn’t run a RCT to determine the solution. The mechanic fixes the problem! As our knowledge of the body grows, medicine should look more like car repair: precise, targeted, and not reliant on averages.

Closely related is the rise of personalized medicine. As I wrote in A New FDA for the Age of Personalized, Molecular Medicine:

Each patient is a unique, dynamic system and at the molecular level diseases are heterogeneous even when symptoms are not. In just the last few years we have expanded breast cancer into first four and now ten different types of cancer and the subdivision is likely to continue as knowledge expands. Match heterogeneous patients against heterogeneous diseases and the result is a high dimension system that cannot be well navigated with expensive, randomized controlled trials. As a result, the FDA ends up throwing out many drugs that could do good.

RCTs tell us about average treatment effects, but the more we treat patients as unique, the less relevant those averages become.

AI holds a lot of promise for more effective, better targeted drugs but the full promise will only be unlocked if the FDA also adapts.