Category: Medicine

An RCT on AI and mental health

Young adults today face unprecedented mental health challenges, yet many hesitate to seek support due to barriers such as accessibility, stigma, and time constraints. Bite-sized well-being interventions offer a promising solution to preventing mental distress before it escalates to clinical levels, but have not yet been delivered through personalized, interactive, and scalable technology. We conducted the first multi-institutional, longitudinal, preregistered randomized controlled trial of a generative AI-powered mobile app (“Flourish”) designed to address this gap. Over six weeks in Fall 2024, 486 undergraduate students from three U.S. institutions were randomized to receive app access or waitlist control. Participants in the treatment condition reported significantly greater positive affect, resilience, and social well-being (i.e., increased belonging, closeness to community, and reduced loneliness) and were buffered against declines in mindfulness and flourishing. These findings suggest that, with purposeful and ethical design, generative AI can deliver proactive, population-level well-being interventions that produce measurable benefits.

That is from a new paper by Julie Y.A. Cachia, et.al. A single paper or study is hardly dispositive, even when it is an RCT. But you should beware of those, such as Jon Haidt and Jean Twenge, who are conducting an evidence-less jihad against AI for younger people.

Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Is involuntary hospitalization working?

From Natalia Emanuel, Valentin Bolotnyy, and Pim Welle:

The involuntary hospitalization of people experiencing a mental health crisis is a widespread practice, as common in the US as incarceration in state and federal prisons and 2.4 times as common as death from cancer. The intent of involuntary hospitalization is to prevent individuals from harming themselves or others through incapacitation, stabilization and medical treatment over a short period of time. Does involuntary hospitalization achieve its goals? We leverage quasi-random assignment of the evaluating physician and administrative data from Allegheny County, Pennsylvania to estimate the causal effects of involuntary hospitalization on harm to self (proxied by death by suicide or overdose) and harm to others (proxied by violent crime charges). For individuals whom some physicians would hospitalize but others would not, we find that hospitalization nearly doubles the probability of being charged with a violent crime and more than doubles the probability of dying by suicide or overdose in the three months after evaluation. We provide evidence of housing and earnings disruptions as potential mechanisms. Our results suggest that on the margin, the system we study is not achieving the intended effects of the policy.

Here is the abstract online at the AEA site. I am looking forward to seeing more of this work.

GDPR is worse than you had thought

We examine how data privacy regulation affects healthcare innovation and research collaboration. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) aims to enhance data security and individual privacy, but may also impose costs to data collection and sharing critical to clinical research. Focusing on the pharmaceutical sector, where timely access and the ability to share patient-level data plays an important role drug development, we use a difference-in-differences design exploiting variation in firms’ pre-GDPR reliance on EU trial sites. We find that GDPR led to a significant decline in clinical trial activity: affected firms initiated fewer trials, enrolled fewer patients, and operated at fewer trial sites. Overall collaborative clinical trials also declined, driven by a reduction in new partnerships, while collaborations with existing partners modestly increased. The decline in collaborations was driven among younger firms, with little variation by firm size. Our findings highlight a trade- off between stronger privacy protections and the efficiency of healthcare innovation, with implications for how regulation shapes the rate and composition of subsequent R&D.

That is from Jennifer Kao and Sukhun Kang, here is the online abstract for the AEA meetings.

Crime and the Welfare State

Several recent papers claim that expanding programs like Medicaid reduces crime (e.g. here). I’ve been skeptical, not because of weaknesses in any particular paper, but just because the results feel a bit too aligned with social-desirability bias and we know that the underlying research designs can be fragile. As a result, my priors haven’t moved much. The first paper using a genuine randomized controlled trial now reports no effect of Medicaid expansion on crime.

Those involved with the criminal justice system have disproportionately high rates of mental illness and substance-use disorders, prompting speculation that health insurance, by improving treatment of these conditions, could reduce crime. Using the 2008 Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, which randomly made some low-income adults eligible to apply for Medicaid, we find no statistically significant impact of Medicaid coverage on criminal charges or convictions. These null effects persist for high-risk subgroups, such as those with prior criminal cases and convictions or mental health conditions. In the full sample, our confidence intervals can rule out most quasi-experimental estimates of Medicaid’s crime-reducing impact.

Finkelstein, Miller, and Baicker (WP).

It could still be the case that very targeted interventions–say making sure that released criminals get access to mental health care–could do some good but there’s unlikely to be any general positive effect.

A similar story is found in Finland where a large RCT on a guaranteed basic income found zero effect on crime

This paper provides the first experimental evidence on the impact of providing a guaranteed basic income on criminal perpetration and victimization. We analyze a nationwide randomized controlled trial that provided 2,000 unemployed individuals in Finland with an unconditional monthly payment of 560 Euros for two years (2017-2018), while 173,222 comparable individuals remained under the existing social safety net. Using comprehensive administrative data on police reports and district court trials, we estimate precise zero effects on criminal perpetration and victimization. Point estimates are small and statistically insignificant across all crime categories. Our confidence intervals rule out reductions in perpetration of 5 percent or more for crime reports and 10 percent or more for criminal charges.

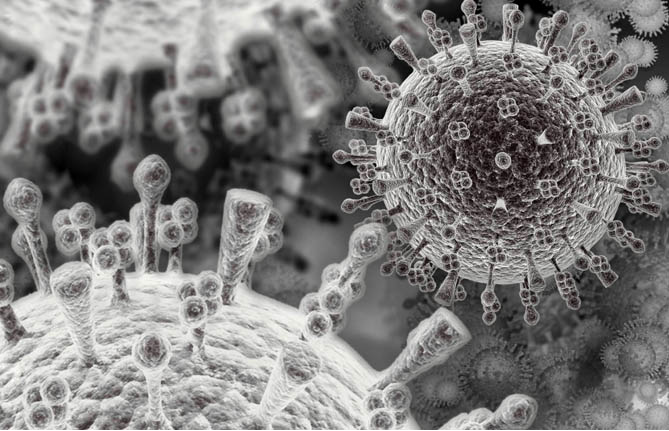

My 2011 Review of Contagion

I happened to come across my 2011 review of the Steven Soderberg movie, Contagion and was surprised at how much I was thinking about pandemics prior to COVID. In the review, I was too optimistic about the CDC but got the sequencing gains right. I continue to like the conclusion even if it is a bit too clever by half. Here’s the review (no indent):

Contagion, the Steven Soderberg film about a lethal virus that goes pandemic, succeeds well as a movie and very well as a warning. The movie is particularly good at explaining the science of contagion: how a virus can spread from hand to cup to lip, from Kowloon to Minneapolis to Calcutta, within a matter of days.

One of the few silver linings from the 9/11 and anthrax attacks is that we have invested some $50 billion in preparing for bio-terrorism. The headline project, Project Bioshield, was supposed to produce vaccines and treatments for anthrax, botulinum toxin, Ebola, and plague but that has not gone well. An unintended consequence of greater fear of bio-terrorism, however, has been a significant improvement in our ability to deal with natural attacks. In Contagion a U.S. general asks Dr. Ellis Cheever (Laurence Fishburne) of the CDC whether they could be looking at a weaponized agent. Cheever responds:

Someone doesn’t has to weaponize the bird flu. The birds are doing that.

That is exactly right. Fortunately, under the umbrella of bio-terrorism, we have invested in the public health system by building more bio-safety level 3 and 4 laboratories including the latest BSL3 at George Mason University, we have expanded the CDC and built up epidemic centers at the WHO and elsewhere and we have improved some local public health centers. Most importantly, a network of experts at the department of defense, the CDC, universities and private firms has been created. All of this has increased the speed at which we can respond to a natural or unnatural pandemic.

In 2009, as H1N1 was spreading rapidly, the Pentagon’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency asked Professor Ian Lipkin, the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, to sequence the virus. Working non-stop and updating other geneticists hourly, Lipkin and his team were able to sequence the virus in 31 hours. (Professor Ian Sussman, played in the movie by Elliott Gould, is based on Lipkin.) As the movie explains, however, sequencing a virus is only the first step to developing a drug or vaccine and the latter steps are more difficult and more filled with paperwork and delay. In the case of H1N1 it took months to even get going on animal studies, in part because of the massive amount of paperwork that is required to work on animals. (Contagion also hints at the problems of bureaucracy which are notably solved in the movie by bravely ignoring the law.)

It’s common to hear today that the dangers of avian flu were exaggerated. I think that is a mistake. Keep in mind that H1N1 infected 15 to 30 percent of the U.S. population (including one of my sons). Fortunately, the death rate for H1N1 was much lower than feared. In contrast, H5N1 has killed more than half the people who have contracted it. Fortunately, the transmission rate for H5N1 was much lower than feared. In other words, we have been lucky not virtuous.

We are not wired to rationally prepare for small probability events, even when such events can be devastating on a world-wide scale. Contagion reminds us, visually and emotionally, that the most dangerous bird may be the black swan.

Innovations in Health Care

The latest issue of the journal Innovations focuses on health care and is excellent. It’s a very special issue–a double Tabarrok issue!

My paper, Operation Warp Speed: Negative and Positive Lessons for New Industrial Policy, asks what can learn from the tremendous success of OWS about an OWS for X? What are the opportunities and the dangers?

My son Maxwell Tabarrok’s paper is Peptide-DB: A Million-Peptide Database to Accelerate Science. Max’s paper combines economics and science policy. Open databases are a public good and so are underprovided. A case in point is that there is no big database for anti-microbial peptides despite the evident utility of such a database for using ML techniques to create new antibiotics. The NIH and other organizations have successfully filled this gap with databases in the past such as PubChem, the HGP, and ProteinDB. A million-peptide database is well within their reach:

The existing data infrastructure for antimicrobial peptides is tiny and scattered: a few thousand sequences with a couple of useful biological assays are scattered across dozens of data providers. No one in science today has the incentives to create this data. Pharma companies can’t make money from it and researchers can’t produce any splashy publications. This means that researchers are duplicating the expensive legwork of collating and cleaning all of this

data and are not getting optimal results, as this is simply not enough information to take full advantage of the ML approach. Scientific funding organizations, including the NIH and the NSF, can fix this problem. The scientific knowledge required to massively scale the data we have on antimicrobial peptides is well established and ready to go. It wouldn’t be too expensive or take too long to get a clean dataset of a million peptides or more, and to have detailed information on their activity against the most important resistant pathogens as well as its toxicity to human cells. This is well within the scale of the successful projects these organizations have funded in the past, including PubChem, the HGP, and ProteinDB.

Naturally, I am biased towards Tabarrok-articles but another important paper is Reorganizing the CDC for Effective Public Health Emergency Response by Gowda, Ranasinghe, and Phan. As Michael Lewis wrote in The Premonition by the time of COVID the CDC had became more akin to an academic department than a virus fighting agency:

The CDC did many things. It published learned papers on health crises, after the fact. It managed, very carefully, public perception of itself. But when the shooting started, it leapt into the nearest hole, while others took fire.

Gowda, Ranasinghe, and Phan agree.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed significant weaknesses in the CDC’s response system. Its traditional strengths in testing, pathogen dentification, and disease investigation and tracking faltered. The legacy of Alexander Langmuir, a pioneering epidemiologist who infused the CDC with epidemiological principles in the 1950s, now seems a distant memory. Tasks as basic as collecting and providing timely COVID-19 data, along with data analysis and epidemiological modeling—both of which should have been the core capability of the CDC—became alarmingly difficult and had to be handled by nongovernmental organizations, such as the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center.

A closer examination of the CDC’s workforce composition reveals the root cause: a mere fraction of its employees are epidemiologists and data scientists. The agency has seen an increasing emphasis on academic exploration at the expense of on the-ground action and support for frontline health departments. (Armstrong & Griffin, 2022).

The authors propose to reinvigorate the CDC by integrating it with the more practical and active U.S. Public Health Service. This is a very good suggestion.

For one more check out Bai, Hyman and Silver as a primer on Improving Health Care. The entire issue is excellent.

Pharma supply is elastic

The crux of the problem is that the IRA imposes price caps that shorten the effective life of a patent and applies those price controls even to later-approved uses. Thirteen years after FDA approval, biologics, which are typically infused or injected, become subject to price controls. For small-molecule drugs, typically pills or tablets, the window is only nine years. The clock starts at a drug’s first approval, leaving a follow-on or alternative use, approved years later, an insufficient period to make up the cost of research.

Two weeks ago, a study I conducted with colleagues at the University of Chicago appeared in Health Affairs. It reveals how much these provisions harm cancer research. In reviewing every Food and Drug Administration-approved cancer drug between 2000 and 2024, we found a large part of innovation in cancer treatment takes place after a therapy is first approved. About 42% of the 184 cancer therapies that were initially approved during that period had follow-on approvals—involving new uses or “indications” for an existing drug—such as treating additional cancer types or being used earlier in the disease, when treatment outcomes tend to be better.

This cumulative progress through follow-on discoveries is a big driver of new cancer treatments, the largest drug class making up about 35% of the overall FDA pipeline. Cancer drugs are generally first tested in patients with late-stage disease, after which the drug is studied for use in earlier stages of that cancer and for new uses, including treating other cancers. Our study found that 60% of follow-on drugs treated earlier stages than the initial drugs. This is important because treating earlier stages is often more successful than when a cancer has spread more.

But that cumulative progress depends on incentives for sustained research well after the first FDA approval—often years of additional trials and investments. And those incentives were killed by the IRA.

Make Africa Healthy Again

In the late 1990s, South Africa’s President Thabo Mbeki decided that mainstream science had AIDS wrong. A small circle of “truth-tellers” convinced him that AIDS came from poverty and malnutrition, not a virus. He warned that anti-retroviral therapy (ART) was toxic and that pharmaceutical companies were poisoning Africans for profit.

His government stalled the rollout of ART. Health Minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang pushed garlic, beetroot, and lemon as medicine. “Nutrition is the basis for good health,” she said, insisting that exercise and diet, not Western drugs, were the real treatment. She warned that antiretrovirals had side effects, including cancer, that the establishment was hiding. When scientists showed data, she waved it off: “No churning of figures after figures will deter me from telling the truth to the people of the country.”

The result was a public health disaster: hundreds of thousand of preventable deaths (see also here and here).

A reminder of what happens when authority trades evidence for ideology.

Big, Fat, Rich Insurance Companies

In my post, Horseshoe Theory: Trump and the Progressive Left, I said:

Trump’s political coalition isn’t policy-driven. It’s built on anger, grievance, and zero-sum thinking. With minor tweaks, there is no reason why such a coalition could not become even more leftist. Consider the grotesque canonization of Luigi Mangione, the (alleged) murderer of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. We already have a proposed CA ballot initiative named the Luigi Mangione Access to Health Care Act, a Luigi Mangione musical and comparisons of Mangione to Jesus. The anger is very Trumpian.

In that light, consider one of Trump’s recent postings:

THE ONLY HEALTHCARE I WILL SUPPORT OR APPROVE IS SENDING THE MONEY DIRECTLY BACK TO THE PEOPLE, WITH NOTHING GOING TO THE BIG, FAT, RICH INSURANCE COMPANIES, WHO HAVE MADE $TRILLIONS, AND RIPPED OFF AMERICA LONG ENOUGH.

Why are US Clinical Trials so Expensive?

Dave Ricks, CEO of Eli Lilly, speaking on the excellent Cheeky Pint Podcast (hosted by John Collison, sometimes joined by Patrick as in this episode) had the clearest discussion of why US clinical trial costs are so expensive that I have read.

One point is obvious once you hear it: Sponsors must provide high-end care to trial participants–thus because U.S. health care is expensive, US clinical trials are expensive. Clinical trial costs are lower in other countries because health care costs are lower in other countries but a surprising consequence is that it’s also easier to recruit patients in other countries because sponsors can offer them care that’s clearly better than what they normally receive. In the US, baseline care is already so good, at least at major hospital centers where you want to run clinical trials, that it’s more difficult to recruit patients. Add in IRB friction and other recruitment problems, and U.S. trial costs climb fast.

Patrick

I looked at the numbers. So, apparently the median clinical trial enrollee now costs $40,000. The median US wage is $60,000, so we’re talking two thirds. Why and why couldn’t it be a 10th or a hundredth of what it is?David (00:10:50):

Yeah, brilliant question and one we’ve spent a lot of time working on…“Why does a trial cost so much?” Well, we’re taking the sickest slice of the healthcare system that are costing the most. And we’re ingesting them. We’re taking them out of the healthcare system and putting them in a clinical trial. Typically we pay for all care. So we are literally running the healthcare system for those individuals and that is in some ways for control, because you want to have the best standard of care so your experiment is properly conducted and it’s not just left to the whims of hundreds of individual doctors and people in Ireland versus the US getting different background therapies. So you standardize that, that costs money because sort of leveling up a lot of things, but then also in some ways you’re paying a premium to both get the treating physicians and have great care to get the patient. We don’t offer them remuneration, but they get great care and inducement to be in the study because you’re subjecting yourself quite often, not all the case, but to something other than the standard of care, either placebo or this. Or, in more specialized care, often it’s standard care plus X where X could actually be doing harm, not good. So people have to go into that in a blinded way and I guess the consideration is you’ll get the best care.Patrick (00:12:51):

Of the $40,000. How much of that should I look at as inducement and encouragement for the patient and how much should I look at it as the cost of doing things given the regulatory apparatus that exists?David (00:13:02):

The patient part is the level up part and I would say 20, 30% of the cost of studies typically would be this. So you’re buying the best standard of care, you’re not getting something less. That’s medicine costs, you’re getting more testing, you’re getting more visits, and then there is a premium that goes to institutions, not usually to the physician, the institution to pay for the time of everybody involved in it plus something. We read a lot about it in the NIH cuts, the 60% Harvard markup or whatever. There’s something like that in all clinical trials too. Overhead coverage, whatnot. But it’s paying for things that aren’t in the trial.Patrick (00:13:40):

US healthcare is famously the most expensive in the world. Yes. Do you run trials outside the US?David (00:13:44):

Yeah, actually most. I mean we want to actually do more in the US. This is a problem I think for our country. Take cancer care where you think, okay, what’s the one thing the US system’s really good at? If I had cancer, I’d come to the US, that’s definitely true. But only 4% of patients who have cancer in the US are in clinical trials. Whereas in Spain and Australia it’s over 25%.And some of that is because they’ve optimized the system so it’s easier to run and then enroll, which I’d like to get to, people in the trials. But some of it is also that the background of care isn’t as good. So that level up inducement is better for the patient and the physician. Here, the standard’s pretty good, so people are like, “Do I want to do something where there’s extra visits and travel time?” There’s another problem in the US which is, we have really good standards of care but also quite different performing systems and we often want to place our trials in the best performing systems that are famous, like MD Anderson or the Brigham. And those are the most congested with trials and therefore they’re the slowest and most expensive. So there’s a bit of a competition for place that goes on as well.

But overall, I would say in our diabetes and cardiovascular trials, many, many more patients are in our trials outside the US than in and that really shouldn’t be other than cost of the system. And to some degree the tuning of the system, like I mentioned with Spain and Australia toward doing more clinical trials. For instance, here in the US, everywhere you get ethics clearance, we call it IRB. The US has a decentralized system, so you have to go to every system you’re doing a study in. Some countries like Australia have a single system, so you just have one stop and then the whole country is available to recruit those types of things.

Patrick (00:15:31):

You said you want to talk about enrollment?David (00:15:32):

Yeah, yeah. It’s fascinating. So drug development time in the industry is about 10 years in the clinic, a little less right now. We’re running a little less than seven at Lilly, so that’s the optimization I spoke about. But actually, half of that seven is we have a protocol open, that means it’s an experiment we want to run. We have sites trained, they’re waiting for patients to walk in their door and to propose, “Would you like to be in the study?” But we don’t have enough people in the study. So you’re in the serial process, diffuse serial process, waiting for people to show up. You think, “Wow, that seems like we could do better than that. If Taylor Swift can sell at a concert in a few seconds, why can’t I fill an Alzheimer’s study? There seem to be lots of patients.” But that’s healthcare. It’s very tough. We’ve done some interesting things recently to work around that. One thing that’s an idea that partially works now is culling existing databases and contacting patients.Patrick (00:16:27):

Proactive outreach.

See also Chertman and Teslo at IFP who have a lot of excellent material on clinical trial abundance.

Lots of other interesting material in this episode including how Eli Lilly Direct—driven largely by Zepbound—has quickly become a huge pharmacy. The direct-to-consumer model it represents could be highly productive as more drugs for preventing disease are developed. I am not as anti-PBM as Ricks and almost everyone in the industry are but I will leave that for another day.

Here is the Cheeky Pint Podcast main page.

More From Less: Optimizing Vaccine Doses

During COVID, I argued strongly that we should cut the Moderna dose in order to expand supply. In a paper co-authored with Witold Więcek, Michael Kremer and others, we showed that a half dose of Moderna was more effective than a full dose of AstraZenecs and that doubling the effective Moderna supply could have saved many lives.

It’s not just about COVID. My co-author on the COVID paper, Witold Więcek, has found other examples where a failure to run dose optimization trials cost lives:

Take the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. For years after its introduction, countries administered it as a three-dose series. Then additional evidence emerged; eventually, a single dose proved to be non-inferior. This policy shift, driven by updated World Health Organization (WHO) guidance, has been a game-changer—massively reducing delivery costs while expanding coverage in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). But it took 16 years from regulatory approval to WHO recommendation. Had this change been implemented just five years earlier, the paper estimates that 150,000 lives could have been saved.

Knowing the potential for dose optimization should encourage us to take a closer look at what we can do now. Więcek points to two high-opportunity projects:

- The pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) is already Gavi’s top cost driver, consuming $1 billion of its 2026–2030 budget. But new WHO SAGE guidance, from March 2025, suggests that in countries with consistently high coverage (≥80–90 percent over five years), either one of three shots could be dropped, or each of the three doses can be lowered to 40 percent of the standard dose. While implementation requires sufficient epidemiological surveillance, its cost would be offset by significant savings in vaccine costs: a retrospective analysis suggests that for the 2020–25 period this approach could have led to as much as $250 million in savings.

- New tuberculosis vaccines, currently in phase 2–3 trials, are another high-impact example. Given initial promising results, a future vaccine could prove highly effective, but may also become a significant cost driver for countries and/or Gavi—and optimization may prove highly beneficial both in terms of health and economic value.

Witold’s new paper is here and here is excellent summary blog post from which I have drawn.

Addendum: See also my paper on Bayesian Dose Optimization Trials and from Mike Doherty Particles that enhance mRNA delivery could reduce vaccine dosage and costs.

Incentives matter, and supply is elastic

Now we read that in a Harvard job market paper, by Olivia Zhao with co-author Edward Kong:

Pharmaceutical firms’ incentives to develop new drugs stem from expected profitability. We explore how market exclusivity, a policy that shapes these expectations, influences pharmaceutical innovation. First, we estimate the effects of extending market exclusivity for antibiotics, a drug class where private returns to development historically had not internalized the high social value of new innovation. Using a difference-in-differences approach, we find that a policy that approximately doubled the market exclusivity period for certain antibiotics increased innovative activity. Patent f ilings for antibiotics increased by 47%, and we find suggestive evidence that preclinical studies and phase 3 trial initiations also increased under the policy. Building on these empirical findings, we estimate a structural model of firms’ drug development decisions to predict how market exclusivity extensions of varying lengths would affect innovation in antibiotics and other therapeutic areas. Our reduced form and structural findings suggest that market exclusivity—especially if targeted to high-social-value, low-market-return areas—can be an effective tool for realigning incentives and stimulating innovation, but stress that baseline market size and interactions between market and patent exclusivities affect this policy lever’s impacts.

Here is the paper, I guess for such work, intended for such an audience, one does not refer to history’s greatest villain? And here is their paper on market incentives and antibiotics. Via Nicholas Decker.

“Gender without Children”

What would the lives of women look like if they knew from an early age that they would not have children? Would they make different choices about human capital or early career investments? Would they behave differently in the marriage market? Would they fare better in the labor market? In this paper, we follow 152 women diagnosed with the Mayer-Rokitanski-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) type I syndrome. This congenital condition, diagnosed at puberty, is characterised by the absence of the uterus in otherwise phenotypically normal 46, XX females. Using granular health registries matched with administrative data from Sweden, we confirm that MRKH is not associated with worse health, nor with differential pre-diagnosis characteristics, and that it has a large negative impact on the probability to ever live with a child. Relative to women from the general population, women with the condition have better educational outcomes, tend to marry and divorce at the same rate, but mate with older men, and hold significantly more progressive beliefs regarding gender roles. The condition has also very large positive effects on earnings and employment. Dynamics reveal that most of this positive effect emerges around the arrival of children in women in the general population, with little difference before. We also find that women with MRKH perform as well as men in the labor market in the long run. Results confirm that “child penalties” on the labor market trajectories of women are large and persistent and that they explain the bulk of the remaining gender gap.

That is from recent work by Tatiana Pazem, with co-authors Camille Landais, Peter Lundberg, Erik Plug & Johan Vikstrom. Tatiana is on the job market from LSE, with her main job market paper being “Pension Reforms and Consumption in Retirement: Evidence from French Transactions and Bank Data.”

The microfoundations of the baby boom?

Between 1936 and 1957, fertility rates in the U.S. increased 62 percent and the maternal mortality rate declined by 93 percent. We explore the effects of changes in maternal mortality rates on white and nonwhite fertility rates during this period, exploiting contemporaneous or lagged changes in maternal mortality at the state-by-year level. We estimate that declines in maternal mortality explain 47-73 percent of the increase in fertility between 1939 and 1957 among white women and 64-88 percent of the increase in fertility among nonwhite women during our sample period.

Here is the full article by Christopher Handy and Katharine Shester, via the excellent Kevin Lewis. Overall, I take this as a negative for the prospect of another, future baby boom? We just cannot make maternity all that much safer, starting from current margins.

Privatizing Law Enforcement: The Economics of Whistleblowing

The False Claims Act lets whistleblowers sue private firms on behalf of the federal government. In exchange for uncovering fraud and bringing the case, whistleblowers can receive up to 30% of any recovered funds. My work on bounty hunters made me appreciate the idea of private incentives in the service of public goals but a recent paper by Jetson Leder-Luis quantifies the value of the False Claims Act.

Leder-Luis looks at Medicare fraud. Because the government depends heavily on medical providers to accurately report the services they deliver, Medicare is vulnerable to misbilling. It helps, therefore, to have an insider willing to spill the beans. Moreover, the amounts involved are very large giving whistleblowers strong incentives. One notable case, for example, involved manipulating cost reports in order to receive extra payments for “outliers,” unusually expensive patients.

On November 4, 2002, Tenet Healthcare, a large investor-owned hospital company, was sued under the False Claims Act for manipulating its cost reports in order to illicitly receive additional outlier payments. This lawsuit was settled in June 2006, with Tenet paying $788 million to resolve these allegations without admission of guilt.

The savings from the defendants alone were significant but Leder-Luis looks for the deterrent effect—the reduction in fraud beyond the firms directly penalized. He finds that after the Tenet case, outlier payments fell sharply relative to comparable categories, even at hospitals that were never sued.

Tenet settled the outlier case for $788 million, but outlier payments were around $500 million per month at the time of the lawsuit and declined by more than half following litigation. This indicates that outlier payment manipulation was widespread… for controls, I consider the other broad types of payments made by Medicare that are of comparable scale, including durable medical equipment, home health care, hospice care, nursing care, and disproportionate share payments for hospitals that serve many low-income patients.

…the five-year discounted deterrence measurement for the outlier payments computed is $17.46 billion, which is roughly nineten times the total settlement value of the outlier whistleblowing lawsuits of $923 million.

[Overall]…I analyze four case studies for which whistleblowers recovered $1.9 billion in federal funds. I estimate that these lawsuits generated $18.9 billion in specific deterrence effects. In contrast, public costs for all lawsuits filed in 2018 amounted to less than $108.5 million, and total whistleblower payouts for all cases since 1986 have totaled $4.29 billion. Just the few large whistleblowing cases I analyze have more than paid for the public costs of the entire whistleblowing program over its life span, indicating a very high return on investment to the FCA.

As an aside, Leder-Luis uses synthetic control but allows the controls to come from different time periods. I’m less enthused by the method because it introduces another free parameter but given the large gains at small cost from the False Claims Act, I don’t doubt the conclusion:

The results of this analysis suggest that privatization is a highly effective way to combat fraud. Whistleblowing and private enforcement have strong deterrence effects and relatively low costs, overcoming the limited incentives for government-conducted antifraud enforcement. A major benefit of the False Claims Act is not just the information provided by the whistleblower but also the profit motive it provides for whistleblowers to root out fraud.