Category: Law

If you have the right to die, you should have the right to try!

Ruxandra Teslo asks a good question:

I have a curiosity: why is it the case that it is easier to get MAID in Canada than it is to access experimental treatments which carry a higher risk? In the past, I used to think ppl do not like “deaths caused by the medical system”, but for MAID the prob of death is 100%…

The Canadians may be somewhat inconsistent on this point. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has been consistent and has rejected medical self-defense arguments for physician assisted suicide and let stand an appeals court ruling that patients do not have a right to access drugs which have not yet been permitted for sale by the FDA (fyi, I was part of an Amici Curiae brief for this case).

Hat tip for the post title to Jason Crawford.

Think through the situation one step further

Many of you got upset when I mentioned the possibility that parents use smart phone software to control the social media usage of their kids. There was an outcry about how badly those systems work (is that endogenous?). But that is missing the point.

If you wish to limit social media usage, mandate that the phone companies install such software and make it more effective. Or better yet commission or produce a public sector app to do the same, a “public option” so to speak. Parents can then download such an app on the phone of their children, or purchase the phone with the app, and manipulate it as they see fit.

If you do not think government is capable of doing that, why think they are capable of running an effective ban for users under the age of sixteen? Maybe those apps can be hacked but we all know the “no fifteen year olds” solution can be hacked too, for instance by VPNs or by having older friends set up the account.

My proposal has several big advantages:

1. It keeps social media policy in the hands of the parents and away from the government.

2. It does not run the risk of requiring age verification for all users, thus possibly banishing anonymous writing from the internet.

3. The government does not have to decide what constitutes a “social media site.”

Just have the government commission a software app that can give parents the control they really might want to have. I am not myself convinced by the market failure charges here, but I am very willing to allow a public option to enter the market.

The fact that this option occasions so little interest from the banners I find highly indicative.

“Tough on crime” is good for young men

Using data from hundreds of closely contested partisan elections from 2010 to 2019 and a vote share regression discontinuity design, we find that narrow election of a Republican prosecutor reduces all-cause mortality rates among young men ages 20 to 29 by 6.6%. This decline is driven predominantly by reductions in firearm-related deaths, including a large reduction in firearm homicide among Black men and a smaller reduction in firearm suicides and accidents primarily among White men. Mechanism analyses indicate that increased prison-based incapactation explains about one third of the effect among Black men and none of the effect among White men. Instead, the primary channel appears to be substantial increases in criminal conviction rates across racial groups and crime types, which then reduce firearm access through legal restrictions on gun ownership for the convicted.

That is from a new paper by Panka Bencsik and Tyler Giles. Via M.

I guess Mexico is solving for the equilibrium?

For some while I have wondered what would happen if the U.S. military sought to assist Mexico in taking out one of the top drug lords. I suppose now we are finding out. A few points:

1. There is a good chance a few more drug lords will be hit. It makes no sense to get involved just to take out one guy (supply is elastic!). Sheinbaum is doing this, so it is not just the oddities of Trumpland at work here. Presumaby the goal is to shift the entire equilibrium.

2. The cartels would do better to lay low for a while, rather than making this a big public issue. The virulence of their response indicates they are probably pretty scared. Of course the actual decisions here are being taken by (threatened) individuals, not by the (persisting) “cartels.”

3. “Cartels” is an overused word here. They are more like loose syndicates, and by no means are they always colluding with each other.

4. Perhaps there is a new “Trump doctrine,” namely to focus on going after lead individuals, rather than governments or institutional structures. We already did that in Venezuela, and there is talk of that being the approach in Iran. If so, that is a change in the nature of warfare, and of course others may copy it too, including against us. Is there a chance they have tried already?

5. With this action, which seems to have U.S: involvement at least on the intelligence side (possibly more), we are also sending a message to Iran.

6. I believe my post from this morning is holding up pretty well. What the U.S. is supplying here is “more decisive action,” rather than some new, detailed understanding of the Mexican dilemma. See also my Free Press Latin America column from October.

7. In its most extreme instantiation, today’s action represents a willingness of the U.S. to get involved in a Mexican civil war of sorts. I do not expect matters to take that path, as the last time U.S. troops had direct involvement in Mexico was 1916-1919. “Convergence to some warning shots” is a more likely equilibrium outcome here. Nonetheless such an escalatory scenario is not off the table, do note that American foreign policy has been returning to much earlier eras in a number of regards.

8. This story is not over.

Why the “Lesser Included Action” Argument for IEEPA Tariffs Fails

The Supreme Court yesterday struck down Trump’s IEEPA tariffs, holding that the statute’s authorization to “regulate… importation” doesn’t include the power to impose tariffs. The majority’s strongest argument is simple: every time Congress actually delegates tariff authority, it uses the word “duty,” caps the rate, sets a time limit, and requires procedural prerequisites. IEEPA has none of these.

The dissent pushes back with an intuitively appealing argument: IEEPA authorizes the President to prohibit imports entirely, so surely it authorizes the lesser action of merely taxing them. If Congress handed over the nuclear option, why would it withhold the conventional weapon? Indeed in his press conference Trump, in his rambling manner, made exactly this argument:

“I am allowed to cut off any and all trade…I can destroy the trade, I can destroy the country, I’m even allowed to impose a foreign country destroying embargo…I can do anything I want to do to them…I’m allowed to destroy the country, but I can’t charge a little fee.”

The argument is superficially appealing but it fails due to a standard result in principal-agent theory.

Congress wants the President to move fast in a real emergency, but it doesn’t want to hand over routine control of trade policy. The right delegation design is therefore a screening device: give the President authority he will exercise only when the situation is truly an emergency.

An import ban works as a screening device precisely because it is very disruptive. A ban creates immediate and substantial harm. It is a “costly signal.” A President who invokes it is credibly saying: this is serious enough that I am willing to absorb a large cost. Tariffs, in contrast, are cheaper–especially to the President. Tariffs raise revenue, which offsets political pain. Tariff incidence is diffuse and easy to misattribute—prices creep, intermediaries take blame, consumers don’t observe the policy lever directly. Most importantly tariffs are adjustable, which makes them a weapon useful for bargaining, exemptions, and targeted favors. Tariffs under executive authority implicitly carry the message–I am the king; give me a gold bar and I will reduce your tariffs. Tariff flexibility is more politically appealing than a ban and thus a less credible signal of an emergency. The “lesser-included” argument gets the logic backwards. The asymmetry is the point.

Not surprisingly, the same structure appears in real emergency services. A fire chief may have the authority to close roads during an emergency but that doesn’t imply that the fire chief has the authority to impose road tolls. Road closure is costly and self-limiting — it disrupts traffic, generates immediate complaints, and the chief has every incentive to lift it as soon as possible. Tolls are cheap, adjustable, and once in place tend to persist; they generate revenue that can fund the agency and create constituencies for their continuation. Nobody thinks granting a fire chief emergency closure authority implicitly grants them taxing authority, even if the latter is a lesser authority. The closure and toll instruments have completely different political economy properties despite operating on the same roads.

The majority reaches the right conclusion by noting that tariffs are a tax over which Congress, not the President, has authority. That is constitutionally correct but the deeper question is why the Framers lodged the taxing power in Congress — and the answer is political economy. Revenue instruments are especially easy for an executive to exploit because they can be targeted. The constitutional rule exists to solve that incentive problem.

Once you see that, the dissent’s “greater includes the lesser” inference collapses on its own terms. A principal can rationally authorize an agent to take a dramatic emergency action while withholding the cheaper, revenue-lever not despite the fact that it seems milder, but because of it. The blunt instrument is self-limiting. The revenue instrument is not. That asymmetry is what the Constitution’s categorical division of powers preserves — and what an open-ended emergency delegation would destroy.

A Republic, if you can keep it

The conclusion of Justice Gorsuch’s concurrence in the tariff case:

For those who think it important for the Nation to impose more tariffs, I understand that today’s decision will be disappointing. All I can offer them is that most major decisions affecting the rights and responsibilities of the American people (including the duty to pay taxes and tariffs) are funneled through the legislative process for a reason. Yes, legislating can be hard and take time. And, yes, it can be tempting to bypass Congress when some pressing problem

arises. But the deliberative nature of the legislative process was the whole point of its design. Through that process, the Nation can tap the combined wisdom of the people’s elected representatives, not just that of one faction or man. There, deliberation tempers impulse, and compromise hammers

disagreements into workable solutions. And because laws must earn such broad support to survive the legislative process, they tend to endure, allowing ordinary people to plan their lives in ways they cannot when the rules shift from day to day. In all, the legislative process helps ensure each of us has a stake in the laws that govern us and in the Nation’s future. For some today, the weight of those virtues is apparent. For others, it may not seem so obvious. But if history is any guide, the tables will turn and the day will come when those disappointed by today’s result will appreciate the legislative process for the bulwark of liberty it is.

The Cassidy Report on the FDA

Senator Bill Cassidy (R-La.) released a new report on how to modernize the FDA. It has some good material.

… FDA’s process for reviewing new products can be an unpredictable “black box.” FDA teams can differ greatly in the extent to which they require testing or impose standards that are not calibrated to the relevant risks. The perceived disconnect between the forward leaning rhetoric and thought leadership of senior FDA officials and cautious reviewer practice creates further unpredictability. This uncertainty dampens investment and increases the time it takes for patients to receive new therapies.

Companies report that they face a “reviewer lottery,” where critical questions hinge on the approach of a small number of individuals at FDA. Some FDA review teams are creative and forward-leaning, helping developers design programs and overcome obstacles to get needed products to patients, without cutting corners. FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE), for example, is repeatedly identified as a model for providing predictable yet flexible options for bringing new drugs to cancer patients. OCE is now a dialogue-based regulatory paradigm that has facilitated efforts by academia, industry, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and others to develop new cancer therapies and launch innovative programs and pilots like Project Orbis, RealTime Oncology Review.

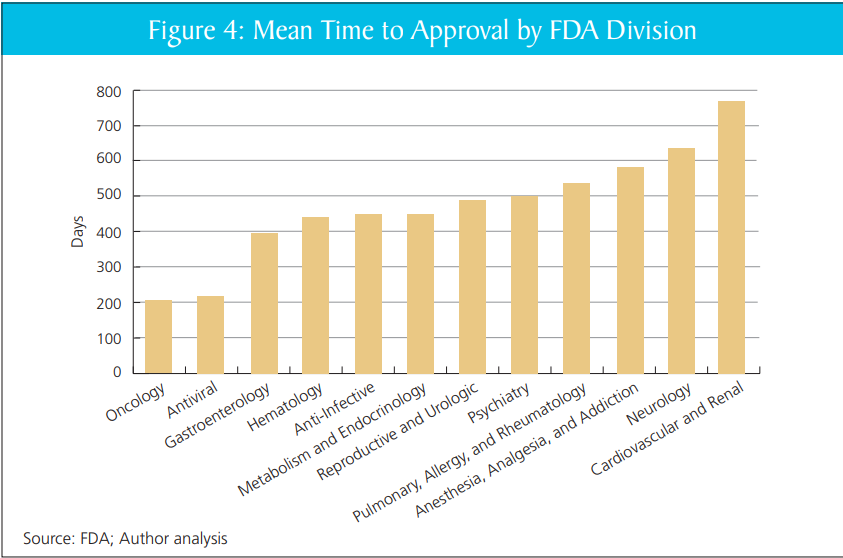

That’s quite right. In my report with DiMasi and Milne, we show that review times vary markedly within the FDA, across divisions, without clear cause. Put aside the big questions of FDA or no FDA–scaling the practices of the better-performing divisions would likely yield large gains.

Mike Doherty further asks the AI what Alex Tabarrok would think of the Cassidy report. It replies:

Strongest features: It correctly diagnoses FDA as a bottleneck to innovation, emphasizes “least burdensome” evidence, calls for streamlined pathways (505(b)(2)-style for biologics, biosimilar simplification), and worries about U.S. losing early-phase trials to other countries. This is very much in Tabarrok’s wheelhouse: regulation as a hidden tax on innovation and growth.

Weakest features: It rarely quantifies tradeoffs, almost never confronts the “invisible graveyard” of patients who never see therapies because of delay, and treats reforms as marginal tweaks rather than testing fundamentally different regulatory models (e.g., insurance-based approval, private certification, or sunset/experimentation with parallel regimes).

If you imagine this as a draft memo handed to Tabarrok, he’d likely say: “Good directionally; now add 50% more economics, 50% more quantification, and 100% more willingness to experiment with institutional competition.”

Yeah, pretty good.

Addendum: In other FDA news see also Adam Kroetsch on Will Bayesian Statistics Transform Trials?

Addendum 2: FDA has now agreed to review Moderna’s flu vaccine which is good although the course reversal obviously speaks to the unpredictability of the FDA.

Minimum Wages for Gig Workers Can’t Work

In 2017, I analyzed the Uber Tipping Equilibrium:

What is the effect of tipping on the take-home pay of Uber drivers? Economic theory offers a clear answer. Tipping has no effect on take home pay. The supply of Uber driver-hours is very elastic. Drivers can easily work more hours when the payment per ride increases and since every person with a decent car is a potential Uber driver it’s also easy for the number of drivers to expand when payments increase. As a good approximation, we can think of the supply of driver-hours as being perfectly elastic at a fixed market wage. What this means is that take home pay must stay constant even when tipping increases.

…If Uber holds fares constant, the higher net wage (tips plus fares) will attract more drivers but as the number of drivers increases their probability of finding a rider will fall. The drivers will earn more when driving but spend less time driving and more time idling. In other words, tipping will increase the “driving wage,” but reduce paid driving-time until the net hourly wage is pushed back down to the market wage.

A paper by Hall, Horton and Knoepfle showed that’s exactly what happened.

More recently, in 2024, Seattle implemented “PayUp”, a pay package for gig workers like DoorDash workers that required a minimum wage based on the time worked and miles travelled for each offer. Note that this is not a minimum wage for all workers but for one type of worker in a large market. For this reason, we can use the same analysis as with Uber tipping. The supply of workers is very elastic and essentially fixed at the market wage for workers of similar skill. Thus, we would expect a zero effect on net pay.

Here is a recent NBER paper by An, Garin and Kovak looking at the effects of the Seattle law:

We find that the minimum pay law raised delivery pay per task….At the same time, the policy led to a reduction in the number of tasks completed by highly attached incumbent drivers (but not an increase in exit from delivery work), completely offsetting increased pay per task and leading to zero effect on monthly earnings. We find evidence that drivers experienced more unpaid idle time and longer distances driven between tasks…Using a simple model of the labor market for platform delivery drivers, we show that our evidence is consistent with free entry of drivers into the delivery market driving down the task-finding rate until expected earnings return to their pre-reform level.

All of this is a general result of the Happy Meal Fallacy.

India’s AI wedding buffet

Shruti Rajagopalan surveys much of the AI policy debate in India. Excerpt:

If there is a single domain where India’s AI ambitions will succeed or fail, it is energy. And energy in India is not a technology problem. It is a political economy problem, arguably the most intractable one the country faces.

India’s peak electricity demand hit 250 GW in May 2024, up from 143 GW a decade earlier. The IEA forecasts 6.3 percent annual growth through 2027, faster than any major economy. Cooling demand alone could reach 140 GW of peak load by 2030. One number captures the trajectory. For each incremental degree in daily average temperature, peak demand now rises by more than 7 GW. In 2019 the figure was half that. India is getting hotter, richer, and more electricity-hungry simultaneously.

State-controlled distribution companies have accumulated $83.7 billion in debt because energy prices have been politically distorted for decades. Over 50 GW of renewable capacity sits underutilized. About 60 GW is stranded behind inadequate transmission. The shortage is financial and infrastructural, not resource-based. Without reforming distribution pricing, governance, and grid investment ($50 billion estimated by 2035), new renewable capacity will not become reliable electricity. It will become another line item on a DISCOM balance sheet no one wants to read.

India’s electricity reaches consumers through 72 distribution companies, 44 of them state-owned, collectively the most financially distressed utilities in the world. Accumulated losses stood at ₹6.92 trillion ($76.89 billion) as of March 2024, rising every year despite five government bailouts since 2002.

Substantive throughout.

Taxing Beta, Exempting Alpha: A Benchmark-Based Inheritance Regime

This paper proposes a generational benchmark inheritance regime as a structural replacement for the federal estate tax. By distinguishing between systemic market returns (Beta) and active value creation (Alpha), the regime captures the passive growth of capital at generational boundaries while fully exempting idiosyncratic surplus. Using a Pareto tail interpolation (α ≈ 1.163) calibrated to Federal Reserve wealth data, we estimate baseline annual revenue of approximately $295 billion under conservative assumptions. This revenue is sufficient to finance a 2.1 percentage point reduction in the OASDI payroll tax, shifting the fiscal burden from labor to underperforming dynastic capital. Unlike continuous wealth taxes, the regime requires no new valuation machinery, relying exclusively on existing estate and gift tax procedures. We situate the proposal within the Jeffersonian principle of usufruct and the modern literature on optimal inheritance taxation.

The cocaine problem seems to be getting worse again

Colombian coca cultivation fell dramatically between 2000 and 2015, a period that saw intense U.S.-backed eradication and interdiction efforts. That progress reversed in 2015, when peace talks and legal rulings in Colombia opened enforcement gaps. Coca plantation has since increased to record levels, which coincided with a sharp rise in cocaine-related overdose deaths in the U.S. We estimate how much of that rise can be causally attributed to Colombia’s new coca boom. Leveraging the unforeseen coca supply shock and cross-county differences in pre-shock cocaine exposure, we find that the surge in supply caused an immediate rise in overdose mortality in the U.S. Our analysis estimates on the order of 1,000–1,500 additional U.S. deaths per year in the late 2010s can be attributed to Colombia’s cocaine boom. Implicit annual loss in American statistical life values about $48,000 per hectare of cultivation in Colombia. If left untamed, the current level of coca cultivation (over 230,000 ha in 2022) may impose on the order of $10 billion per year in costs via overdose fatalities.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Xinming Du, Benjamin Hansen, Shan Zhang, and Eric Zou.

I Regret to Inform You that the FDA is FDAing Again

I had high hopes and low expectations that the FDA under the new administration would be less paternalistic and more open to medical freedom. Instead, what we are getting is paternalism with different preferences. In particular, the FDA now appears to have a bizarre anti-vaccine fixation, particularly of the mRNA variety (disappointing but not surprising given the leadership of RFK Jr.).

The latest is that the FDA has issued a Refusal-to-File (RTF) letter to Moderna for their mRNA influenza vaccine, mRNA-1010. An RTF means the FDA has determined that the application is so deficient it doesn’t even warrant a review. RTF letters are not unheard of, but they’re rare—especially given that Moderna spent hundreds of millions of dollars running Phase 3 trials enrolling over 43,000 participants based on FDA guidance, and is now being told the (apparently) agreed-upon design was inadequate.

Moderna compared the efficacy of their vaccine to a standard flu vaccine widely used in the United States. The FDA’s stated rationale is that the control arm did not reflect the “best-available standard of care.” In plain English, that appears to mean the comparator should have been one of the ACIP-preferred “enhanced” flu vaccines for adults 65+ (e.g., high-dose/adjuvanted) rather than a standard-dose product.

Out of context, that’s not crazy but it’s also not necessarily wise. There is nothing wrong with having multiple drugs and vaccines, some of which are less effective on average than others. We want a medical armamentarium: different platforms, different supply chains, different side-effect profiles, and more options when one product isn’t available or isn’t a good fit. The mRNA vaccines, for example, can be updated faster than standard vaccines, so having an mRNA option available may produce superior real-world effectiveness even if it were less efficacious in a head-to-head trial.

In context, this looks like the regulatory rules of the game are being changed retroactively—a textbook example of regulatory uncertainty destroying option value. STAT News reports that Vinay Prasad personally handled the letter and overrode staff who were prepared to proceed with review. Moderna took the unusual step of publicly releasing Prasad’s letter—companies almost never do this, suggesting they’ve calculated the reputational risk of publicly fighting the FDA is lower than the cost of acquiescing.

Moreover, the comparator issue was discussed—and seemingly settled—beforehand. Moderna says the FDA agreed with the trial design in April 2024, and as recently as August 2025 suggested it would file the application and address comparator issues during the review process.

Finally, Moderna also provided immunogenicity and safety data from a separate Phase 3 study in adults 65+ comparing mRNA-1010 against a licensed high-dose flu vaccine, just as FDA had requested—yet the application was still refused.

What is most disturbing is not the specifics of this case but the arbitrariness and capriciousness of the process. The EU, Canada, and Australia have all accepted Moderna’s application for review. We may soon see an mRNA flu vaccine available across the developed world but not in the United States—not because it failed on safety or efficacy, but because FDA political leadership decided, after the fact, that the comparator choice they inherited was now unacceptable.

The irony is staggering. Moderna is an American company. Its mRNA platform was developed at record speed with billions in U.S. taxpayer support through Operation Warp Speed — the signature public health achievement of the first Trump administration. The same government that funded the creation of this technology is now dismantling it. In August, HHS canceled $500 million in BARDA contracts for mRNA vaccine development and terminated a separate $590 million contract with Moderna for an avian flu vaccine. Several states have introduced legislation to ban mRNA vaccines. Insanity.

The consequences are already visible. In January, Moderna’s CEO announced the company will no longer invest in new Phase 3 vaccine trials for infectious diseases: “You cannot make a return on investment if you don’t have access to the U.S. market.” Vaccines for Epstein-Barr virus, herpes, and shingles have been shelved. That’s what regulatory roulette buys you: a shrinking pipeline of medical innovation.

An administration that promised medical freedom is delivering medical nationalism: fewer options, less innovation, and a clear signal to every company considering pharmaceutical investment that the rules can change after the game is played. And this isn’t a one-product story. mRNA is a general-purpose platform with spillovers across infectious disease and vaccines for cancer; if the U.S. turns mRNA into a political third rail, the investment, talent, and manufacturing will migrate elsewhere. America built this capability, and we’re now choosing to export it—along with the health benefits.

Immigration and health for elderly Americans

We measure the impact of increased immigration on mortality among elderly Americans, who rely on the immigrant-intensive health and long-term care sectors. Using a shift-share approach we find a strong impact of immigration on the size of the immigrant care workforce: admitting 1,000 new immigrants would lead to 142 new foreign healthcare workers, without evidence of crowd out of native health care workers. We also find striking effects on mortality: a 25% increase in the steady state flow of immigrants to the US would result in 5,000 fewer deaths nationwide. We identify reduced use of nursing homes as a key mechanism driving this result.

That is from a new NBER working paper by

Why is Singapore no longer “cool”?

To be clear, I am not blaming Singapore on this one. But it is striking to me how much Americans do not talk about Singapore any more. They are much, much more likely to talk about Europe or England, for instance. I see several reasons for this:

1. Much of the Singapore fascination came from the right-wing, as the country offered (according to some) a right-wing version of what a technocracy could look like. Yet today’s American political right is not very interested in technocracy.

2. Singapore willingly takes in large numbers of immigrants (in percentage terms), and tries to make that recipe work through a careful balancing act. That approach still is popular with segments of the right-wing intelligentsia, but it is hardly on the agenda today. For the time being, it is viewed as something “better not to talk about.” Especially in light of some of the burgeoning anti-Asian sentiment, for instance from Helen Andrews and some others. It is much more common that Americans talk about foreign countries mismanaging their immigration policies, for instance the UK and Sweden.

3. Singaporean government looks and feels a bit like a “deep state.” I consider that terminology misleading as applied to Singapore, but still it makes it harder for many people to praise the place.

4. Singapore is a much more democratic country than most outsiders realize, though they do have an extreme form of gerrymandering. Whatever you think of their system, these days it no longer feels transgressive, compared to alternatives being put into practice or at least being discussed. Those alternatives range from more gerrymandering (USA) to various abrogations of democracy (potentially all over). In this regard Singapore, without budging much on its own terms, seems like much more of a mainstream country than before. That means there is less to talk about.

4b. Singapore’s free speech restrictions, whatever you think of them, no longer seem so far outside the box. Trump is suing plenty of people. The UK is sending police to knock on people’s doors for social media posts, and so on. That too makes Singapore more of a “normal country,” for better or worse (I would say worse).

5. The notion of an FDI-driven, MNE-driven growth strategy seems less exciting in an era of major tech advances, most of all AI. Singapore seems further from the frontier than a few years ago. People are wishing to talk about pending changes, not predictability, with predictability being a central feature of many Singaporean service exports.

6. If you want to talk about unusual, well-run small countries, UAE is these days a more novel case to consider, with more new news coming out of it.

Sorry Singapore, we are just not talking about you so much right now! But perhaps, in some significant ways, that is a blessing in disguise. At least temporarily. I wrote this post in part because I realize I have not much blogged about Singapore for some years, and I was trying to figure out why.

Addendum, from Ricardo in the comments:

Bryan Caplan on immigration backlash

Tyler tries to cure my immigration backlash confusion, but not to my satisfaction. The overarching flaw: He equivocates between two different versions of “backlash to immigration.”

Version 1: Letting in more immigrants leads to more resistance to immigration.

Version 2: Letting in more immigrants leads to so much resistance to immigration that the total stock of immigration ultimately ends ups lower than it would have been.

Backlash in the first sense is common, but no reason for immigration advocates to moderate. Backlash in the second sense is a solid reason for immigration advocates to moderate, but Tyler provides little evidence that backlash in this sense is a real phenomenon.

Do read the whole thing, but I feel I am obviously right here. Bryan should read newspapers more! If I did not provide much evidence that backlash is a significant phenomenon, it is because I thought it was pretty obvious. A few points:

1. I (and Bryan all the more so) want more immigration than most voters want. But I recognize that if you strongly deny voters their preferences, they will turn to bad politicians to limit migration. So politics should respect voter preferences to a reasonable degree, even though at the margin people such as myself will prefer more immigration, and also better immigration rules and systems.

2. The anti-immigrant politicians who get elected are very often toxic. And across a wide variety of issues. The backlash costs range far wider than just immigration policies. (I do recognize this does not apply in every case, for instance Meloni in Italy seems OK enough and is not a destructive force. She also has not succeeded in limiting migration, and probably cannot do so without becoming toxic. So maybe that story is not over yet. In any case, consider how many of the other populist right groups have a significant pro-Russia element, Russia being right now probably the most evil country in the world.)

3. If immigration runs “out of control” (as voters perceive it) in your country, there will be anti-immigrant backlash in other countries too. For instance in Japan and Poland. Bryan considers only backlash in the single country of origin. In Japan, for instance, voters just handed their PM a new and powerful mandate, in large part because of the immigration issue. The message was “what is happening in other countries, we do not want that happening here.” The globalization of communications and debate increases the scope and power of the backlash effect considerably.

Most of all, it is simply a mistake to let populist right parties become the dominant force in Europe, and sometimes elsewhere as well. You might think it is not a mistake because we need them to limit migration. Well, that is not my view, but I am arguing it is a mistake to get to that margin to begin with.

In short, we need to limit migration to prevent various democracies from going askew. Nothing in that argument contradicts the usual economic (and other) arguments for a lot of immigration being a good thing. And still it is a good thing to try to sell one’s fellow citizens on the case for more immigration. Nonetheless we are optimizing subject to a constraint, namely voter opinion. Why start off an intertemporal bargaining game by trying to seize as much surplus (immigration) as possible? That to me is obvious, more obvious every day I might add.