Category: History

Markets in everything, American Indian edition

I’m mystified by Joel Waldfogel’s claim — and Nike’s claim — that, until now, there have been no markets in shoes just for American Indians.

American Indian shoes have been produced and traded for centuries. Most of all they have been produced by American Indians. Some of them are called moccasins. Here is a bibliography of writings on American Indian footware. Here are native American clothing stores, which also sell shoes. Here is a craft manual for how to make American Indian footwear.

And of course plenty of companies make extra-wide and extra-large shoes, though of course not for American Indians exclusively. There is the Mexican market as well, which caters to many "indigenous shapes," although admittedly on the shorter side.

I like Joel’s book but I think he is far too pessimistic about the prospects for diversity in the modern world. It’s also worth noting that if any group has been victimized and robbed by government, and driven into partial isolation, it is the American Indian.

The Coldest Winter

…this is my first visit to Thomas Keller’s temple of haute cuisine in Yountville, California, and I can’t wait to see whether it lives up to its reputation. More importantly, however, my dining companions are three outstanding chefs from Sichuan province, a heartland of Chinese gastronomy…None of them has ever been to the West before, or had any real encounters with what is known in China as "Western food," and I am as much interested in their reactions to the meal as my own.

Driving down HIghway 29 to the restaurant, I had prepared my guests by casually remarking, "You’re very lucky, because we are going to visit one of the best restaurants in the world."

In the world? asked Lan Guijun. "According to whom?"

..as I warm up to the pleasures of this utterly satisfying dinner, I can’t help noticing that my companions are having a rather different experience. Yu Bo, the most adventurous of the three, is intent of savoring every mouthful and studying the composition of our meal. He is solemn in his concentration. But the other two are simply soldiering on. And for all three of them, I realize with devastating clarity, this is a most difficult, a most alien, a most challenging experience.

They find the creaminess of the sabayon offputting, the rareness of the lamb unhealthy, and the olives to taste like Chinese medicine. Don’t ask about the cheese, and they are amazed that "a bowl of soupy rice" [risotto] could cost so much. A few days of dining later, they find eating salad to be barbaric (it is raw), and sourdough bread to be tough and chewy.

Yu Bo, to my great satisfaction, is pleasantly impressed with the first raw oyster of his life, and even ventures to take a second. When I ask him how they taste, he nods furiously in approval. "Not bad, not bad; a bit like jellyfish."

That is from Gourmet magazine, August 2005 issue. Here is my previous post on inaccessibility and large cultures.

Happiness advice from my wife

My wife, a PhD microbiologist, told me once that when she was at work she felt guilty about not being at home with the kids and when she was at home with the kids she felt guilty about not being at work.

This problem may explain a surprising finding from Betsey Stevenson and one of your leading candidates for "most wanted economist blogger," Justin Wolfers. Stevenson and Wolfers have a new paper showing that happiness is up for men but down for women. They write:

By most objective measures the lives of women in the United States have improved over the

past 35 years, yet we show that measures of subjective well-being indicate that women’s happiness

has declined both absolutely and relative to male happiness. The paradox of women’s declining

relative well-being is found examining multiple countries, datasets, and measures of subjective wellbeing,

and is pervasive across demographic groups. Relative declines in female happiness have eroded

a gender gap in happiness in which women in the 1970s typically reported higher subjective wellbeing

than did men. These declines have continued and a new gender gap is emerging–one with

higher subjective well-being for men.

One reason is suggested by Stevenson in a NYTimes article on her research with Wolfers and similar independent research from Alan Krueger.

Ms. Stevenson was recently having drinks with a business school

graduate who came up with a nice way of summarizing the problem. Her

mother’s goals in life, the student said, were to have a beautiful

garden, a well-kept house and well-adjusted children who did well in

school. “I sort of want all those things, too,” the student said, as

Ms. Stevenson recalled, “but I also want to have a great career and

have an impact on the broader world.”

Opportunity brings opportunity cost.

In the NYTimes article David Leonhardt correctly notes that "Although women have flooded into the work force, American society hasn’t fully come to grips with the change." Alas, all he has to offer as solution is the usual platitudes about subsidized daycare and how men should do more of the housework – peculiar solutions to women’s unhappiness with increased opportunities. Leonhardt should instead have talked to my wife.

As I wrote this post, I asked my wife about her feeling guilty at home and at work but she told me she no longer feels this way. "Really?" I asked, "Why not?"

"I decided to act more like a man and get over it," she responded.

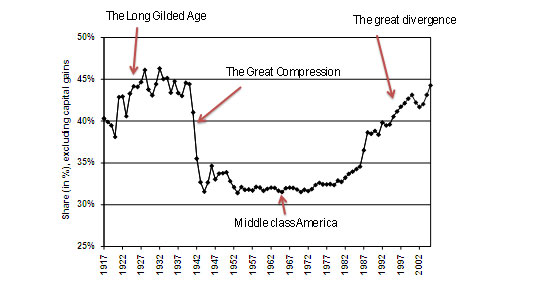

The Great Compression

Paul Krugman recently blogged:

The middle-class society I grew up in didn’t evolve gradually or automatically. It was created,

in a remarkably short period of time, by FDR and the New Deal. As the

chart shows, income inequality declined drastically from the late 1930s

to the mid 1940s, with the rich losing ground while working Americans

saw unprecedented gains.

As you can see, the share of the top ten percent (not counting capital gains) falls steeply at about 1937 and flattens out by about 1942-43, with a slight uptick just afterwards. But I am puzzled by Krugman’s description of the process. A few points:

1. 1937-38 were disastrous years for the American economy and also for the middle class, mostly because of bad contractionary monetary policy. This can be considered a second Great Depression and it aborted a recovery in process. Robert Higgs has shown convincingly that World War II was an economic disaster, look at the figures at consumption don’t be fooled by aggregate gdp which is inflated by production for the war.

2. Therefore I am not sure when the "unprecedented gains" came during this period. Yes 1940 was a year of recovery (and part of 1939) but is the claim that the middle class was created in that year? Surely not but then I am confused.

3. Krugman cites "strong unions, a high minimum wage, and a progressive tax system" as driving the Great Compression — did these factors change so notably in 1937-44?

4. In real terms, relative to the time, the new federal minimum wage of 1938 was not especially high, even compared to the minimum wage today. And the data are for pre-tax incomes, which means that progressive taxation is unlikely the major part of the story about the distribution of pre-tax income (noting the Yglesias caveat that the rate of tax will influence pre-tax incomes through labor supply).

5. Here are some data on U.S. unionization. The history does broadly track Krugman’s time frame, as long as one does not obsess over 1937-43 as being special. Note that optimistic estimates of the union wage premium today run about 15 percent, so it is hard to see unionization as the dominant factor in the change in the distribution of income.

6. The wartime economy, and the scarcity of labor, bid up wages for black workers, women, and many remaining non-drafted male laborers (due to forced saving, however, consumption was low).

7. My explanation of the break in the chart emphasizes a combination of events: top incomes were crushed by the depression of 1937-8, the war economy put a further lid on top of high incomes (for reasons of law and norms; surely the phrase "wartime wage and price controls" deserves to be uttered at least once), and the war economy bid up wages for many people near the bottom and middle of the distribution. The wealthy classes financed a disproportionate chunk of World War II, it seems.

8. Krugman mentions none of the factors listed in #7. Admittedly I may be wrong, but are not those factors obvious candidates for an explanation?

9. It is a vitally interesting question why postwar America stayed at this new percentile distribution of income (more or less), even after recovery from the war. It may be possible to defend a version of Krugman’s broader hypothesis — policy matters for income distribution — in this setting, but the story then puts greater stress on both the equalizing effects of catastrophes and also on path-dependence. That story might also suggest that strongly negative real shocks would be needed once again to make income distribution much more egalitarian.

10. How about this for an alternative story: "Crush the incomes at the top and then make the fat cats pay much higher wages to protect the world and become a superpower. Impose wage and price controls as well. See how long it takes before these distributional effects — which don’t exactly match the distribution of economic talent– reverse themselves in the aggregate." I’m not sure that’s right but at least it seems to match more of the history.

I am sensitive to the claim that many people misinterpret the words of Paul Krugman, so please do read his whole post. If he addresses these matters in more detail in his forthcoming book, I will let you know.

The New York Times: gems from the archives

The Ku Klux Klan

Here is the abstract from the new Roland Fryer and Steve Levitt paper:

The Ku Klux Klan reached its heyday in the mid-1920s, claiming millions

of members. In this paper, we analyze the 1920s Klan, those who joined

it, and the social and political impact that it had. We utilize a wide

range of newly discovered data sources including information from Klan

membership roles, applications, robe-order forms, an internal audit of

the Klan by Ernst and Ernst, and a census that the Klan conducted after

an internal scandal. Combining these sources with data from the 1920

and 1930 U.S. Censuses, we find that individuals who joined the Klan

were better educated and more likely to hold professional jobs than the

typical American. Surprisingly, we find few tangible social or

political impacts of the Klan. There is little evidence that the Klan

had an effect on black or foreign born residential mobility, or on

lynching patterns. Historians have argued that the Klan was successful

in getting candidates they favored elected. Statistical analysis,

however, suggests that any direct impact of the Klan was likely to be

small. Furthermore, those who were elected had little discernible

effect on legislation passed. Rather than a terrorist organization, the

1920s Klan is best described as a social organization built through a

wildly successful pyramid scheme fueled by an army of

highly-incentivized sales agents selling hatred, religious intolerance,

and fraternity in a time and place where there was tremendous demand.

I find this interpretation plausible; for many (evil) people, evil is downright fun, especially if you are bored in the first place. Both Donnie Brasco and The Sopranos capture aspects of this equation.

Google does not generate a non-gated version, let us know in the comments if I missed one.

Why did the Industrial Revolution come to England?

Michael H. Hart’s Understanding Human History is an objectionable book in a variety of regards, but it is another attempt to explain the broad sweep of human history using the concept of IQ. Let’s see what Hart says (pp.365-6) about why the Industrial Revolution came to England:

1. England had a high average IQ

2. England had a relatively high population (compared say to the Nordic countries)

3. England did not have slavery

4. England had intellectual ferment

5. Colonies added to the intellectual ferment of England

6. Unlike Germany or Italy, England was not politically fragmented

7. England had abundant iron ore and coal

8. England had relatively secure property rights

Hart stresses that in Europe only England had all these factors operating in its favor. For our purposes, Hart’s more pluralistic explanation is testament to how large a role the Malthusian model plays in Greg Clark’s book.

Hopeless ideas to which I retain an irrational attachment

Historic India, before Partition, is an idea which appeals greatly to me. Not the colonial version, but the idea of an independent and tolerant India of larger scope.

I don’t pretend to have any good arguments for this idea, and I understand (to some degree) how and why it fell apart. I also understand that historic India was itself not very unified. That is in part what makes my attachment irrational, and perhaps the irrationality is part of the attachment itself.

What is your hopeless idea to which you retain an irrational attachment?

Did industrial policy drive Asian economic growth?

…there is considerable evidence that industrial policy has influenced the sectoral composition of output and trade in Japan. However, rather than being the forward-looking driver that proponents of selective promotion envision, at least in terms of measurable interventions, the evidence suggests that such policy was aimed overwhelmingly at internationally noncompetitive natural-resource-based sectors. Indeed, once general equilibrium considerations are taken into account, in all likelihood the manufacturing sector as a whole experienced negative net resource transfers.

That is from the very interesting Industrial Policy in an Era of Globalization: Lessons from Asia, by Marcus Noland and Howard Pack. This book is a good rebuttal to the claim that Asian economic success was fundamentally driven by industrial policy. I thank a loyal MR reader who sent me this book, as a supplement to exchanges with Dani Rodrik.

Addendum: Do see Rodrik’s response in the comments…

India historical fact of the day

In a mere two years, 500 autonomous and sometimes ancient chiefdoms had been dissolved into fourteen new administrative units of India.

That is from India After Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy, a truly excellent book by Ramachandra Guha, well over 800 pages and yes it will be finished.

By the way, if you live in India, come from India, or have strong ties to India, please keep a special watch on MR over the next few days. I’ll explain more soon.

Water transport and economic development

The French economic historian Maurice Aymard has estimated that the Dutch Republic was the only country in Europe where water transport was appreciably greater than land transport, in terms of tonnage carried. In England it was about 50-50; in Germany the ratio was 1:5, but in France it was 1:10.

That is from Tim Blanning’s The Pursuit of Glory, Europe 1648-1815; here is my previous post on the book.

The World We Have Lost

Four or six draught animals were needed to pull a coach and they had to be changed every 6 to 12 miles, depending on the condition of the roads. In England it was calculated that one horse was needed for every mile of a journey on a well-maintained turnpike road. So, for the 185 miles from Manchester to London, 185 horses had to be kept stabled and fed to deal with the seventeen changes required by the stagecoaches which traveled the route. Those horses in turn required an army of coachmen, postillions, guards, grooms, ostlers and stable-boys to keep them running. As a coach could carry no more than ten passengers, fares were correspondingly high and out of reach of the mass of the population. A journey from Augsburg to Innsbruck by stagecoach, although little more than 60 miles as the crow flies, would have cost an unskilled laborer more than a month’s wages just for the fare.

That is from new and excellent The Pursuit of Glory, Europe 1648-1815, by historian Tim Blanning. The best parts of this book — which are very good indeed — are the early sections on the economic history of transportation.

Here is a previous installment of The World We Have Lost.

History lesson

The Aztecs were soon dominating Central Mexico, and overawed others as they built and extended their empire. While the capital city housed over 200,000, the valley and its surroundings held an addition million people. Thousands of public buildings, canals, and causeways impressed everyone who came, including the Spanish.

Here, or try Charles Mann’s 1491, one of my favorite books. Try reading him on the selective breeding of corn, still one of mankind’s most impressive scientific feats. Or:

The Maya, Inca, and Aztec empires [were] greatly advanced in the topics agriculture, writing, and engineering and astronomy.

You might think that some kind of dysgenic breeding has kicked in since, but a) there is zero evidence for that, and b) it is more plausible to cite a few negative supply shocks. You know, like the pandemic that wiped out 90 percent of the Aztecs or more, their virtual enslavement by the Spanish, the move from trade-based cities to the isolated hacienda system, and the subsequent malnutrition and demoralization and cultural devastation, all of which amounted to perhaps the most extreme destruction of a civilization ever seen.

James Heckman, Nobel Laureate writes:

This paper develops a model of skill formation that explains a variety of findings established in the child development and child intervention literatures. At its core is a technology that is stage-specific and that features self productivity, dynamic complementarity and skill multipliers. Lessons are drawn for the design of new policies to alleviate the consequences of the accident of birth that is a major source of human inequality.

Try these papers too, plus previous MR posts on the Flynn Effect. IQ is worth talking about, but compare Heckman’s models and data to much of the IQ literature — those models are not very well specified, nor given our current state of knowledge about either growth or IQ can they be — and you’ll see I do mean what I am saying.

If you do wish to try a "genetic argument," there is much more evidence for the "predisposition to debilitating alcoholism" claim. I’d estimate that half of the adult males of Oapan — the village I cite and direct descendants of the Aztec empire I might add — are debilitated alcoholics.

Please leave your comments on the already-active previous thread.

China and Industrial Policy

Brad DeLong’s post on China and industrial policy combines a deep knowledge of history, politics and economics. It’s a superb post, one of Brad’s best ever so do read the whole thing then come back here for some minor quibbles.

Brad goes over the top for Deng Xiaoping ("quite possibly the greatest human hero of the twentieth century.") Without denying Deng’s importance, I would say that China’s great leap forward came with the death of Mao Zedong. Once Mao – quite possibly the greatest human killer of the twentieth century – was dead, China could almost not help but improve.

Second, the Chinese people, especially the peasant farmers, deserve a huge amount of credit. Here’s a couple of paragraphs I wrote recently:

The Great Leap Forward was a great leap backward – agricultural land was less productive in 1978 than it had been in 1949 when the communists took over. In 1978, however, farmers in the village of Xiaogang held a secret meeting. The farmers agreed to divide the communal land and assign it to individuals – each farmer had to produce a quota for the government but anything he or she produced in excess of the quota they would keep. The agreement violated government policy and as a result the farmers also pledged that if any of them were to be jailed the others would raise their children.

The change from collective property rights to something closer to private property rights had an immediate effect, investment, work effort and productivity increased. “You can’t be lazy when you work for your family and yourself,” said one of the farmers.

Word of the secret agreement leaked out and local bureaucrats cut off Xiaogang from fertilizer, seeds and pesticides. But amazingly, before Xiaogang could be stopped, farmers in other villages also began to abandon collective property.

Deng and others in the central leadership are to be credited with recognizing a good thing when they saw it but it was the farmers in villages like Xiaogang that began China’s second revolution.

Addendum: For the story of Xiaogang I draw on John McMillan’s very good book, Reinventing the Bazaar.

The Pirates’ Code

James Surowiecki writes:

…pirate ships limited the power of captains and guaranteed crew members a say in the ship’s affairs. The surprising thing is that, even with this untraditional power structure, pirates were, in [Peter] Leeson’s words, among “the most sophisticated and successful criminal organizations in history.”

There is more:

Leeson is fascinated by pirates because they flourished outside the state–and, therefore, outside the law. They could not count on higher authorities to insure that people would live up to promises or obey rules. Unlike the Mafia, pirates were not bound by ethnic or family ties; crews were as remarkably diverse as in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” films. Nor were they held together primarily by violence; while pirates did conscript some crew members, many volunteered. More strikingly, pirate ships were governed by what amounted to simple constitutions that, in greater or lesser detail, laid out the rights and duties of crewmen, rules for the handling of disputes, and incentive and insurance payments to insure that crewmen would act bravely in battle.

Read the whole thing.