Category: History

East Germany, circa 1985

Chris Bertram writes in the comments of MR:

As it happens I spent some time in East Germany in 1984. As I

recall, it was then claimed that the per capita GDP was comparable to

that of the UK. It was immediately obvious to me that the standard of

living for most people was far far lower. But real problem with East

Germany was not its comparative level of economic development or the

level of health care its citizens could receive (rather good,

actually). It was the fact that it was a police state where people were

denied the basic liberties.Given them those liberties and I think you’ve achieved most of

what’s morally important. If they then choose a policy of more leisure

and lower growth or the opposite … that’s up to them. I don’t think

it matters, morally speaking, that they are poorer than Americans are.

I am genuinely puzzled by this. I visited East Berlin — supposedly the showcase of the country – in 1985. Let me try to sound as superficial as possible, in light of the extreme poverty in Africa.

The food was terrible. The cars were a joke, if you even had one. There were hardly shops to be found. I had to spend 40 or so "Ostmarks" and literally could not find a single thing I wanted. I bought a Stendahl book and left the rest of the money on a bench. Few people had the means to travel, even if politics had permitted it. I am skeptical about the health care though I will admit I am not informed. Had the relatively productive people been free to leave, this all would have been much worse. It should also be noted that the country was neither donating much to Africa, nor taking in many immigrants, and again that is not just because of the politics.

Chris and I have a very different notion of what is morally important. I don’t wish to force anyone to be richer than East Berlin circa 1985, but if you give them liberty, almost everyone will try to exceed that level, and not just by a little bit.

What is so great about social democracy anyway?

Andrew Smith, a loyal MR reader, writes:

You said in one of your

recent MR posts that although you did not find the European model

sustainable over the long run, frequent trips to Europe revealed much

in the model that delighted you. I believe you singled out Stockholm…as being a particularly vivid illustration of all that

social democracy could do right.

I, too, am a free-market enthusiast who is delighted by

European cities, but when I think carefully about what delights me I

find that it is less anything developed since World War II and more the

remnants of the Europe that existed before the First World War.

First, there is the dense urban development that created

incredible communities from the rise of Venice in the Middle Ages to

the Paris that Haussmann created in the mid-19th century. I cannot

think of a single community built mostly after World War I that has

much charm and those built mostly after WWII — like the tower

communities that ring Paris — are downright depressing, worse than any

of the strip malls and sprawl American capitalism has produced since

the war.

The regional cuisines, the sidewalk cafes, the specialty merchants, the distinctive aspects of each area’s art and music — it all came about before WWI and now lingers as

a slowly fading twilight of Europe’s high noon. (True, farm subsidies and merchant regulations do help maintain the beautiful countryside and the small shops, but I think Europeans have enough passion for local that both things would mostly survive in a free market.)

What part of the Europe that you enjoy so much owes its existence to social democracy? Just curious.

Excellent points. My answer is twofold. First, social democracy has kept Europe, its high standard of living, and its historical wonders, more or less intact. Through much of 1914-194? this outcome was by no means obvious. I am willing, at times, to resort to crude historicism.

Second, European social democracy offers its citizens the most wonderful vacations elsewhere. I just don’t see how most Americans tolerate only two weeks’ vacation.

(Mind you, I am not lazy; my vacations, done my way, are more strenuous than any work day. In fact I consider a work day my source of relaxatoin. If I have to relax, at least I want to be getting lots done.)

As an aside, I do find contemporary Finland visually attractive, and I believe Lille would please me also, from the photos I have seen.

In any case, Smith’s points should cause us to downgrade that "aesthetic halo of achievement" which social democracy has around many of our heads.

The European Economy Since 1945

An excellent book appeared on my doorstep yesterday, by Barry Eichengreen:

Thus Europe, which had relied on extensive growth in the 1950s and 1960s, had no choice but to switch to intensive growth from the 1970s on. The problem was that institutions tailored to the needs of extensive growth were less suited to the challenges of intensive growth. Bank-based financial systems had been singularly effective at mobilizing resources for investment by existing enterprises using known technologies, but they were less conducive to growth in a period of heightened technological uncertainty. Now the role of finance was to take bets on competing technologies, something for which financial markets were better adapted. The generous employment protections and heavy welfare-state charges that had given labor the security to accept the installation of mass-production technologies now became an obstacle to growth as new firms seeking to explore the viability of unfamiliar technologies became the agents of job creation and productivity improvement. Systems of worker co-determination, in which union representatives occupied seats on big firms’ supervisory boards, had been ideal for helping labor to verify that owners were investing the profits resulting from its wage restraint but now discouraged bosses from taking the tough measures needed to restructure in preparation for the adoption of radical new technologies. State holding companies that had been engines of investment and technical progress were no longer efficient mechanisms for allocating resources in this new era of heightened technological uncertainty. They were increasingly captured by special interests and used to bail out loss-making firms and prop up declining industries.

I have never read a better paragraph on what the European economies have done right and subsequently did wrong. Note that Eichengreen is, broadly, a social democrat. Eichengreen (who is more optimistic about Europe than I am) believes that Europe can turn things around, without chucking the basic model, but he doesn’t for a moment deny that Europe faces an economic crisis relative to the American model.

I am still shocked by the response of the CrookedTimber commentators to my short essay on social democracy over there. It is not just a question of how one reads the productivity and growth numbers, but also there is a commonly accepted narrative of what is wrong with the major European economies. Eichengreen is the one doing service to the social democratic cause.

Hail Robert Fagles

There is a new translation of Virgil’s Aeneid:

There are twin Gates of Sleep.

One, they say, is called the Gate of Horn

and it offers easy passage to all true shades,

The other glistens with ivory, radiant, flawless,

but through it the dead send false dreams up toward the sky.

And here Anchises, his vision told in full, escorts

his son and Sibly both and shows them out now

through the Ivory Gate.Aeneas cuts his way

to the waiting ships to see his crews again,

then sets a course straight on to Caieta’s harbor.

Anchors run from prows, the sterns line the shore.

I don’t know all of the Aeneid translations, but I prefer this to Mandelbaum (my previous first choice), West, or Fitzgerald. The overall approach strikes me as a more accurate Fitzgerald. Highly recommended.

What makes a nation wealthy?

Economists typically explain the wealth of a nation by pointing to good policies and the quality of a country’s institutions. But why do these differences exist in the first place?

Professor Greg Clark of UC Davis, in his new book-length manuscript, resurrects Malthus, counters Jared Diamond (only recently has the European standard of living surpassed that of hunter-gatherer societies), shows the Industrial Revolution came only slowly, and argues that economists overrate the importance of good policy. We can separate out the influence of policy by looking at the differential productivity on the factory floor, across regions. The sheer quality of labor matters more than we used to think. Quality labor attracts capital, which in turn supports good institutions.

Here is the conclusion to my column:

Professor Clark’s idea-rich book may just prove to be the next blockbuster in economics. He offers us a daring story of the economic foundations of good institutions and the climb out of recurring poverty. We may not have cracked the mystery of human progress, but “A Farewell to Alms” brings us closer than before.

Clark also argues that sub-Saharan Africa is poorer than ever before, and that foreign aid worsens a zero-sum Malthusian trap. He makes the startling claim that gains in health are the worst thing we can bring to modern Africa. Here is the full column (by the way, I don’t write the titles or subtitles), which includes a link to Clark’s manuscript.

The book is not yet out, but it is the best of its kind since Guns, Germs, and Steel.

What’s a small recent blip in the data?

…unskilled male wages in England have risen more since the Industrial Revolution than skilled wages, and this result holds for all advanced economies. The wage premium for skilled building workers has declined from about 100 percent in the thirteenth century to 25 percent now.

That is from Gregory Clark’s A Farewell to Alms, p.298.

How much does the past matter?

A lot, according to Comin, Easterly, and Gong:

We assemble a dataset on technology adoption in 1000 B.C., 0 A.D., and

1500 A.D. for the predecessors to today’s nation states. We find that

this very old history of technology adoption is surprisingly

significant for today’s national development outcomes. Although our

strongest results are for 1500 A.D., we find that even technology as

old as 1000 BC matters in some plausible specifications.

Here is the NBER version, here is a free version.

Which British authors were most popular in late nineteenth century India?

A sample of fourteen library catalogs, from across India, revealed that only two authors were in all fourteen: Edward Bulwer-Lytton and Sir Walter Scott. Apparently the embellished novel was popular.

In thirteen of the catalogs were Dickens, Disraeli, and Thackeray.

In twelve of the catalogs were Marie Corelli, F. Marion Crawford, Dumas, George Eliot, Charles Kingsley, Captain Frederick Marryat, G.W.M. Reynolds, and Philip Meadows Taylor.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was in eleven.

The figures are from the new and noteworthy, The Novel: Volume 1, History, Geography, and Culture, edited by Franco Moretti; this volume is a treasure trove of information about the history and early economics of the novel.

How did the British occupy India?

…today’s colonials fight back. Britain occupied India with a tiny force

because the Indians mostly let them, and on the rare occasions when

they rebelled the British (like all the other European colonial powers)

felt free to crush them in the most brutal manner imaginable.

No matter how we compare American and British brutalities (we dropped many bombs on Vietnam), I place greater stock in the railroad (later the car and bus) and the radio. In the early days of British control, most Indians couldn’t get within shouting distance of a fight if they wanted to. The Brits had only to control some key garrisoned cities and some trade routes. Local rulers did the rest. Radio, which spread in the 1920s, told people what was going on and cemented national consciousness. Those technologies heralded the later end of colonialism, with WWII hurrying along the new equilibrium.

Might some future technology might render colonialism more likely (NB: I am not saying "more desirable")? Extreme surveillance is one possiiblity, but this appears far off for poorer locales. More likely is simply that rich countries buy the loyalty of some (smaller) poor countries, as the French seem to have done with Martinique.

If the world’s very poor countries stay in Malthusian traps, how long will it be before wealthy philanthropists can try to "adopt a country"? Measured Haitian gdp, for instance, is only a few billion dollars a year (TC: don’t ask about the storms!). Yes many countries have laws against foreign investment and land ownership, but at some point a correct strategy can put the money to good use. Can an entire corrupt government simply be bought out? Just how much money, and what kind of plan, would a private philanthropist need each year to turn Haiti around, or at least bring it to the standards of Martinique?

Sir Henry Neville

I’ve been reading The Truth Will Out: Unmasking the Real Shakespeare, by Brenda James and William Rubinstein. The book’s major claim is that Sir Henry Neville wrote the works of William Shakespeare. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve never been one for conspiracy theories. I even believe that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone assassin. And I’ve never bought into the attribution of Shakespeare’s works to de Vere; the guy died too soon for the chronology to make sense.

But I found this book — no, "convincing" is too strong a word — but difficult to dismiss. It has the first good arguments I’ve read that Shakespeare, were he the real guy, would have a very different paper trail than what we find. Some of the plays appear to show detailed knowledge of the Continent that Shakespeare did not seem to have. The topics of the plays match Neville’s life and experience closely, right down to the timing. Some scenes from the plays match incidents from Neville’s life, down to some very particular numbers.

To be sure, there is no smoking gun. It is all circumstancial evidence. And we should remain skeptical toward speculative theses which captivate the giddy minds of scholars. But — if this book were a blog post I would link to it.

Here is one brief summary of the argument. Here is a short piece by Rubinstein. Here is a CrookedTimber post. Here is a Times story. Here are links to critiques.

Sentence of wisdom

Optimistically, we find that adjustments to imbalances in the past have generally been smooth, even under a regime as hard as the gold standard.

Here is the full paper (non-gated here), which looks at international adjustments throughout history. Here is a version of the slides. On the more pessimistic side, return differentials across countries do not seem to persist.

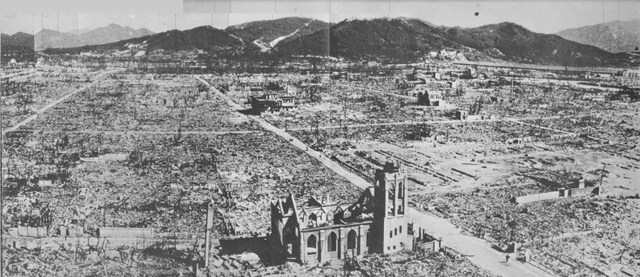

Hiroshima

In case you had forgotten. The Japanese haven’t. Here is the pointer. Here is Thomas Schelling on nuclear weapons. Kim Jong’s favorite movies? "Friday the 13th and Hong Kong action films. He is a big fan of Rambo and James Bond."

Public choice and the Nazis

On average, family members of German soldiers had 72.8 percent of peacetime household income at their disposal. That is nearly double what families of American (36.7) and British soldiers (38.1) received.

Götz Aly’s new and noteworthy Hitler’s Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State tells us how. The sad answer is that the Nazi regime lived off the resources it stole from conquered nations, forced labor, Jews, and refugees.

The magnitude of the theft was much larger than I had thought. In the fiscal year 1938-9, "Aryanization" increased government revenue by 9 percent. At its peak, Nazi theft was able to finance 70 percent of war revenues, noting that "war revenues" is a flow but the concept does not measure the real resource costs of fighting the war. See the book’s appendix for a response to some not totally unjustified criticisms of the author and his methods (the author’s claims seem to be correct as worded but the wording has narrower meaning than might strike an ordinary reader at first glance).

The good news, if you could call it that, is simply that the wartime Nazi regime was less stable than believed and it would have encountered very serious economic and military difficulties once the full plunder was extracted from abroad. If you are looking for a context where the long-run Laffer Curve holds, you’ll find it here.

Race and Culture

The NYTimes reports that in Queens the median income for blacks is above the median income for whites, the only large county in the nation for which that is true. The median income for blacks in Queens, $51,836, is also well above the national median income ($46,000).

What makes the statistics especially interesting is that many of the blacks in Queens are recent immigrants from the West Indies. Malcolm Gladwell, whose own genealogy traces to the West Indies, recognizes the implication:

The implication of West Indian success is that racism does not really

exist at all–at least, not in the form that we have assumed it does.

The implication is that the key factor in understanding racial

prejudice is not the behavior and attitudes of whites but the behavior

and attitudes of blacks–not white discrimination but black culture. It

implies that when the conservatives in Congress say the responsibility

for ending urban poverty lies not with collective action but with the

poor themselves they are right.

but ultimately he can’t accept the implication and offers instead a strained interpretation. West Indian blacks are successful only because, according to Gladwell, they provide a convenient way for whites to distinguish "good" and "bad" blacks allowing themselves to pat themselves on the back for not being racist while at the same time continuing to practice racism against the majority black class.

Gladwell offers scant evidence for his hypothesis, the most interesting point being his claim that Jamaican blacks are perceived as bad citizens in Toronto where they are dominant but as good in New York where they can define themselves in opposition to American blacks. Gladwell’s argument is weak, however, because West Indian blacks distinguish themselves not just in dress or accent but in just those behaviors that also increase income for whites and other successful minorities: they get married and stay married, pursue education, work hard and are entrepreneurial. Gladwell himself notes:

When the first wave of Caribbean immigrants came to New York and

Boston, in the early nineteen-hundreds, other blacks dubbed them

Jewmaicans, in derisive reference to the emphasis they placed on hard

work and education.

The title of the post refers of course to Thomas Sowell’s classic.

Moscow 1941

When the storm broke, people turned to Tolstoy: "During the war," wrote the critic Lidia Ginzburg, "people devoured War and Peace as a way of measuring their own behavior (about Tolstoy they had no doubt: his response to life was wholly adequate). The reader would say to himself: Well then, so what I am feeling is right: that’s just how it should be." War and Peace was the only book the writer Vasili Grossman had time to read while he was a frontline correspondent, and he read it twice. It was broadcast on Moscow Radio, complete, over thirty episodes.

That is from new and noteworthy Moscow 1941: A City and its People at War, by Rodric Braithwaite, recommended.