Category: History

The economics of dueling

Ron Chernow, in his biography of Alexander Hamilton, writes:

Duels were also elaborate forms of conflict resolution, which is why duelists did not automatically try to kill their opponents. The mere threat of gunplay concentrated the minds of antagonists, forcing them and their seconds into extensive renegotiations that often ended with apologies instead of bullets.

Put that into plain English: We have a Rubinstein bargaining game where players fail to reach an agreement, thereby eating up more and more of the pie. Each individual plays "chicken" and hopes the other will give in. But when you approach the precipice…ah…chicken becomes an increasingly dangerous strategy. The time horizon is truncated, "hold out" behavior becomes riskier, and perhaps the negative wealth effect brings individuals to the bargaining table. (It is complicated; rising costs may simply make you keener to wait out your opponent. A mutual increase in risk, however, can boost the likelihood of a bargain.) Then the Coase theorem kicks in and players reach a deal.

Of course to enforce this meeting of the minds, the the probability has to be real that an actual duel will result.

I used to think of duels as an inefficient form of signaling, typically with honor at stake. In contrast, this hypothesis may suggest that pre-duel risk generation is set privately at too low a level. The riskier you make things seem with your potential opponent, the more that subsequent would-be duelers will be scared into an agreement.

The hypothesis also suggests why duels have (mostly) vanished, namely because trading and contract technologies have improved (except in ghettos). The signaling hypothesis can predict either an increase or decrease in duels, depending on whether the demand for honor or life rises more rapidly with income.

Democracy’s Soldiers

In a review of Armageddon, a book on WWII by Max Hastings, James Sheehan makes the following bizarre remark.

Hastings recognizes that the generals’ failure to knock Germany out of

the war in late 1944 reflected the kind of armies they led as much as

their own deficiencies as leaders. The British and American armies were

composed of citizen soldiers, who were usually prepared to do their

duty but were also eager to survive.

The corollary being that citizens of non-democracies were not eager to survive and therefore made better warriors. Uh huh. I could go on but Brad DeLong has a great smackdown.

Was there an Industrial Revolution?

…the best estimates now available suggest no acceleration in the rate of growth of national product per head in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and that one of the implications of this revision of the previous orthodoxy is that the English economy…was much more productive in the middle of the eighteenth century than was once supposed…it is unlikely that England enjoyed any advantage over her neighbours in this regard in the sixteenth century. It would be a major surprise, therefore, if the revised view of the situation c.1750 did not imply that the rate of growth of national product per head for a century or more before 1750 was as high as, or higher than, it was in the century next following.

This turns the spotlight on agriculture, whose centrality to all organic economies is clear by definition. It must figure prominently in any quest for the industrial revolution, despite its apparent exclusion by the oddities of nomenclature.

There are more shocks. Between 1600 and 1800 English per capita income rose by no more than 0.35 percent a year. (At the same time population was roughly doubling, from about 4.2 to 8.7 million.) Such a measured growth rate may sound low but by the standards of the time it was miraculously high. Other economies tended to hold steady or shrink in per capita income, especially in light of growing population.

Could it be that England’s ability to manage per capita growth above zero percent, for an extended period of time, is what give birth to the modern world? Was the Netherlands, with its earlier period of growth and urbanization, in fact the true leader?

On all these issues, and many others, read the new and fascinating collection of essays by E.A. Wrigley, Poverty, Progress, and Population.

Brad DeLong defends Adam Smith

My favorite part:

In The Wealth of Nations, at least, Smith believes that he has

an extraordinarily penetrating and largely new insight: that the market

economy–the "system of natural liberty," he calls it–as an immensely

powerful and benevolent social mechanism for promoting general

prosperity. This is, Smith believes, cause for a revolution in how we

should think about Political Oeconomy. The power and benevolence of the

market is not the only important consideration to take into account in

thinking about questions of Political Oeconomy, but it is the most

important consideration–as important, relatively speaking, as is the

gravity of the sun in calculating the motions of the planets. Just as

you cannot ignore the influence of Jupiter or even the Earth when

calculating the orbit of Mars, so you cannot ignore considerations of

civic humanism or employer collusion or monopoly in thinking about

Political Oeconomy. But to not give pride of place to Smith’s love of

the "system of natural liberty" is to be false to Smith’s thought. And

the guy deserves more respect than that.

Read more here.

Communicating stock prices, circa 1830

In the 1830s a man, every business day, would climb to the top of the dome of the Merchant’s Exchange on Wall Street, where the New York Stock and Exchange Board then held its auctions. There he would signal the opening prices to a man in Jersey City, across the Hudson. That man would signal them in turn to a man at the next steeple or hill, and the prices could reach Philadelphia in about thirty minutes.

That is from John Steele Gordon’s excellent An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power. Here is my previous post on the book.

The ice trade

By the 1830s ice had become a very profitable American export. In 1833 American ice was being shipped as far as Calcutta, when the Tuscany, which had sailed from Boston on May 12, reached the mouth of the Ganges on September 5. Calcutta, one of the hottest and most humid cities on earth, and then the capital of British India, was ninety miles up the Hooghly River, and the population awaited the ice with breathless anticipation. The India Gazette demanded that the ice be admitted duty free and that permission be granted to unload the ice in the cool of the evening. Authorities quickly granted the demands. Frederic Tudor managed to get about a hundred tons of ice to Calcutta, and the British there gratefully bought it all at a profit for the American investors of about $10,000.

By the 1850s American ice was being exported regularly to nearly all tropical ports, including Rio de Janeiro, Bombay, Madras, Hong Kong, and Batavia (now Jakarta). In 1847 about twenty-three thousand tons of ice was shipped out of Boston to foreign ports on ninety-five ships, while nearly fifty-two thousand tons was shipped to southern American ports.

That is from John Steele Gordon’s An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Power. This new book is the best single volume treatment of American economic history I have read, highly recommended. Here is a review, and note that the book’s perspective is Hamiltonian, not Jeffersonian.

And here is more on the ice trade. Here are good photos of the Norwegian ice trade, and yes they were exporters not importers.

A Thanksgiving Lesson

It’s one of the ironies of American history that when the Pilgrims first arrived at Plymouth rock they promptly set about creating a communist society. Of course, they were soon starving to death.

Fortunately, "after much debate of things," Governor William Bradford ended corn collectivism, decreeing that each family should keep the corn that it produced. In one of the most insightful statements of political economy ever penned, Bradford described the results of the new and old systems.

[Ending corn collectivism] had very good success, for it made all hands very industrious,

so as much more corn was planted than otherwise

would have been by any means the Governor or any other

could use, and saved him a great deal of trouble, and gave

far better content. The women now went willingly into the

field, and took their little ones with them to set corn;

which before would allege weakness and inability; whom

to have compelled would have been thought great tyranny

and oppression.The experience that was had in this common course and

condition, tried sundry years and that amongst godly and

sober men, may well evince the vanity of that conceit of

Plato’s and other ancients applauded by some of later

times; that the taking away of property and bringing in

community into a commonwealth would make them happy

and flourishing; as if they were wiser than God. For this

community (so far as it was) was found to breed much confusion

and discontent and retard much employment that

would have been to their benefit and comfort. For the

young men, that were most able and fit for labour and

service, did repine that they should spend their time and

strength to work for other men’s wives and children without

any recompense. The strong, or man of parts, had no

more in division of victuals and clothes than he that was

weak and not able to do a quarter the other could; this

was thought injustice. The aged and graver men to be

ranked and equalized in labours and victuals, clothes, etc.,

with the meaner and younger sort, thought it some indignity

and disrespect unto them. And for men’s wives to be

commanded to do service for other men, as dressing their

meat, washing their clothes, etc., they deemed it a kind of

slavery, neither could many husbands well brook it. Upon

the point all being to have alike, and all to do alike, they

thought themselves in the like condition, and one as good

as another; and so, if it did not cut off those relations that

God hath set amongst men, yet it did at least much diminish

and take off the mutual respects that should be preserved

amongst them. And would have been worse if they

had been men of another condition. Let none object this

is men’s corruption, and nothing to the course itself. I answer,

seeing all men have this corruption in them, God in

His wisdom saw another course fitter for them.

Among Bradford’s many insights it’s amazing that he saw so clearly how collectivism failed not only as an economic system but that even among godly men "it did at least much diminish and take off the mutual respects that should be preserved amongst them." And it shocks me to my core when he writes that to make the collectivist system work would have required "great tyranny

and oppression." Can you imagine how much pain the twentieth century could have avoided if Bradford’s insights been more widely recognized?

New economic history project

This sounds wonderful:

EH.Net Encyclopedia of Economic and Business History is designed to provide students and laymen with high quality reference articles in the field. Articles for the Online Encyclopedia are written by experts, screened by a group of authorities, and carefully edited.

Here is the prestigious advisory board.

Thanks to Brad DeLong for the pointer.

Venerable British traditions

“The Cost of This Building was 495,544 Rupees”

Carved into Prince Albert Hall, erected in Jaipur, India in 1886. It is also known as Ram Niwas Garden Central Museum.

Michael Grant passes away at 89

Here is the obituary, here is a New York Times account.

Do you ever find the history of the ancient world baffling? Grant’s books have been the place to go. Here is his book on the ancient Mediterranean, but read the whole lot.

My favorite things Indian

Being here is number one at the moment, but here are a few specifics:

1. My favorite Indian musician – I have to go with Zakir Hussain; yes the CDs are wonderful but they do not compare with seeing him live. Honorary mentions go to Ali Akhbar Khan (sarod) and L. Subramaniam (violin).

2. My favorite Indian movie – Bollywood stands or falls as a whole, but if I had to pick one film, it is the classic Mother India; this 1957 movie is arguably the defining moment of Indian cinema.

3. My favorite Indian novel – Rushdie is the obvious favorite, but I will opt for Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy. Better than any Dickens but Bleak House. And did you know that he was an errant economics Ph.d. student at Stanford when he wrote the manuscript?

4. My favorite Indian artist – Indian miniatures are a favorite, but we must go with named artists for this category. How about Nandalal Bose, the Bengali painter from the early twentieth century? Here are more nice pictures by him.

5. Favorite Indian chess player – Vishwanathan Anand is a no-brainer. India has a history of supercalculators, so how about this guy? You give him two and a half hours on his clock and he still uses only thirty minutes, and that is against world class competition. He used to be ranked number two in the world, though he has slipped in the last few years.

The man who killed the draft

The influence of Milton Friedman in ending conscription is well-known. But an economist named William Meckling arguably played a larger role, read the story. Many of you will know that Meckling, working with Michael Jensen, made seminal contributions to the theory of the debt-equity ratio. Here’s hoping that Congress meant its recent vote.

And consider these words from David Henderson:

Many of you who have made or are now making your fortunes would not have done so if the draft had been in the way. Consider Bill Gates, who in 1975 dropped out of Harvard to start Microsoft: during the draft years, young men like him who left college risked being certified as prime military meat. Computer programmers and other IT workers, who often do their best work relatively early in life, regularly drop out of college now because high-paying, interesting jobs beckon. If we still had the draft — even a peacetime draft — many wouldn’t have that chance.

People often wonder why today’s 20-somethings have such entrepreneurial spirit. One reason, I believe, is that a whole generation has grown up without the draft looming over its head.

Thanks to Bryan Caplan for the pointer.

If only it were true

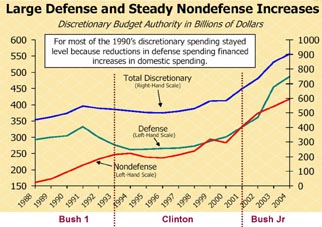

George Bush during the second debate:

Non-homeland, non-defense discretionary spending was raising at 15 percent a year when I got into office. And today it’s less than 1 percent, because we’re working together to try to bring this deficit under control.

Kevin Drum makes it simple.

Here’s the truth about non-defense discretionary spending over the past six administrations:

Nixon/Ford: 6.8% per year

Carter: 2.0% per year

Reagan: -1.3% per year

Bush 1: 4.0% per year

Clinton: 2.5% per year

Bush Jr: 8.2% per year

All percentages are adjusted for inflation. The chart on the right shows raw figures for the past three administrations (from the Congressional Budget Office).

The origins of Monopoly

The board game that is, not the economic phenomenon. It appears to have sprung from the Henry George movement. George, of course, was obsessed with land monopoly and its unproductive rents. It is no accident that the board game assigns such extortionary power to landholders:

On January 5, 1904, Lizzie J. Magie, a Quaker woman from Virginia, received a patent (view patent) for a board game. Lizzie Magie belonged to a tax movement led by Philadelphia-born Henry George; the movement supported the theory that the renting of land and real estate produced an unearned increase in land values that profited a few individuals (landlords) rather than the majority of the people (tenants). Henry George proposed a single federal tax based on land ownership believing a single tax would discourage speculation and encourage equal opportunity.

Lizzie Magie wanted to use her game, which she called “The Landlord’s Game” as a teaching device for George’s ideas. The Landlord’s Game and Monopoly are very similar, except all the properties in Magie’s game are rented not acquired as in Monopoly and instead of names like “Park Place” and “Marvin Gardens” one finds “Poverty Place”, “Easy Street” and “Lord Blueblood’s Estate”. The objectives of each game are also very different. In Monopoly the idea of the game is to buy and rent or sell property so profitably that one becomes the wealthiest player and eventually monopolist. In The Landlord’s Game, the object was to illustrate how (under the system of land tenure) the landlord had an advantage over other enterprisers and to show how the single tax could discourage speculation.

When I was young I had a counterproductive obsession with owning the yellow properties.

Here is the full story. Here is an NPR account of the origins of monopoly. I am indebted to an email from Lauren Landsburg and Russ Roberts for the initial historical reference.

More Lost Nukes

Concerning yesterday’s post on missing nuclear weapons Gerald Hanner wrote to say:

I once flew with one of the people involved in that lost nuke in South Carolina. It was being carried by a B-47, and they were on their way to a forward-deployed base in England to pull alert. For takeoff the weapon (no one in the business calls them “bombs”) is not pinned into the release mechanism so that it could be released if there was an aircraft emergency after takeoff. Since the “pit” was not installed in the weapon there was no chance of a nuclear detonation. In any case, after a safe takeoff the copilot went back to the bomb bay to place a safety pin in the release mechanism; the pin would not go into the slot it was designed for. After calling back to their departure base to discuss the problem, someone on the ground suggested jiggling the release mechanism a bit to properly align the parts. The copilot did. The next transmission from the aircraft was, “Shit! We dropped it!” The weapon released and went right through the closed bomb bay door; those were heavy dudes back then. You’ve read the rest of the story.

Dave Walker of Lockjaw’s Lair wrote to report on a still-missing nuclear weapon in North Carolina.

It was just after midnight on January 24, 1961. A B52G Stratofortress (one of the greatest airplanes ever to cast a shadow on this fine Earth, IMHO) suffered structural failure in its right wing near Faro, NC. The plane carried two MK39 hydrogen bombs.

The two weapons were jettisoned from the plane. One parachuted safely to the ground, receiving minimal damage. The other plummetted to Earth, partially breaking up on impact. Part of the weapon, however, was never found. The lost portion was the uranium-containing part, as well. Crews dug to a depth of 50 feet in the boggy field, but could never retrieve the warhead. To this day, the lost weapon continues to lie in this field.

Radioactivity tests have come up negative, and the Air Force has purchased an easement on the property to prevent anyone digging. If you’d like to read further on the case of the lost warhead, check out this link.