Category: Political Science

Against Transcendence

Deirdre McCloskey gave the inaugural James M. Buchanan Lecture last week, The Hobbes Problem: From Machiavelli to Buchanan. It was a good start to the series, eloquent, learned, and heartfelt. McCloskey argued that the Hobbesian programme of building the polis on prudence alone, a program to which the moderns, Rawls, Buchanan, Gauthier and others have contributed is barren. A good polis must be built upon all 7 virtues, both the pagan and transcendent, these being courage, justice, temperance, and prudence but also faith, hope and love (agape).

In the lecture, McCloskey elided the difficult problems of the transcendent virtues especially as they apply to politics (I expect a more complete analysis in the forthcoming book). Faith, hope, and love sound pleasant in theory but in practice there is little agreement on how these virtues are instantiated. It was love for their eternal souls that motivated the inquisitors to torture their victims. President Bush wants to save Iran…with nuclear bombs. Faith in the absurd is absurd. Thanks but no thanks.

Since we can’t agree on the transcendent virtues injecting them into politics means intolerance and division. Personally, I’d be happy to see the transcendent virtues fade away but I know that’s

unrealistic. The next best thing, therefore, is to insist that the transcendent virtues be reserved for civil society and at all costs be kept out of politics. The pagan virtues alone provide room for agreement in a cosmpolitan society, a society of the hetereogeneous.

Of course, in all this I follow Voltaire:

Take a view of the Royal Exchange in London, a place more venerable

than many courts of justice, where the representatives of all nations

meet for the benefit of mankind. There the Jew, the Mahometan, and the

Christian transact together, as though they all professed the same

religion, and give the name of infidel to none but bankrupts. There

the Presbyterian confides in the Anabaptist, and the Churchman depends

on the Quaker’s word. At the breaking up of this pacific and free

assembly, some withdraw to the synagogue, and others to take a glass.

This man goes and is baptized in a great tub, in the name of the

Father, Son, and Holy Ghost: that man has his son’s foreskin cut off,

whilst a set of Hebrew words (quite unintelligible to him) are mumbled

over his child. Others retire to their churches, and there wait for the

inspiration of heaven with their hats on, and all are satisfied.If one religion only were allowed in England, the Government would

very possibly become arbitrary; if there were but two, the people would

cut one another’s throats; but as there are such a multitude, they all

live happy and in peace.

Inconvenient questions about immigration

MR readers will know I hold a relatively cosmopolitan stance, sympathetic to immigration, including the immigration of low-skilled labor. But notice the tension with Milton Friedman’s classic stance that businesses should maximize profit only, without regard for broader social concerns. If businesses have this liberty to behave selfishly, why do not governments? Similarly, cannot a mother give priority to her child, rather than selling it to save ten babies in Haiti? Why should governments be the unique carrier of cosmopolitan obligations?

I see a few possible stances:

1. Randall Parker thinks Western governments should be be elitist, nationally selfish, and determined to maximize national average IQ.

2. Perhaps government holds special obligations. Robert Goodin argued that government should be utilitarian while other institutions pursue selfish concerns. But where does this dichotomy come from, and still, why should the concerns of a government stretch past its citizenry?

3. Peter Singer and Shelley Kagan believe that all entities, whether collective or individual, should take the most cosmopolitan view possible. For Singer this includes the consideration of other species. Few people are willing to live the implications of this.

4. We have not (yet?) found a universally correct perspective from all vantage points. We have public obligations, private obligations, and no clear algorithm for squaring the two. We nonetheless can find local improvements consistent with both, or which do not greatly damage our private interests. Freer immigration, even when costly, is one of the cheapest and most liberty-consistent ways of addressing our (admittedly ill-defined) obligations to others. But surely those obligations are not zero. This implies, by the way, that Friedman’s maxim is not strictly accurate.

Note that libertarians are often extreme nationalists when it comes to foreign policy ("Darfur is no concern of ours") but extreme cosmopolitans when it comes to immigration.

My views are closest to #4. Our inability to fully embrace cosmopolitanism is a central reason why the case for open borders is not more persuasive. Many people hear the cosmopolitan call and sense, instinctively, that something is wrong. But when we view the argument in explicitly economic terms — what is the best way of satisfying marginal obligations which are surely not zero? — the case for a liberal immigration policy is stronger.

The Tullock paradox: why is there so little lobbying?

…the economist Thomas Stratmann has estimated that just $192,000 of contributions from the American sugar industry in 1985 made the difference between winning and losing a crucial House vote that delivered more than $5 billion of subsidies over the five subsequent years.

That is one example of many. Our government controls trillions, but lobbying expenditures are a small fraction of gdp. One explanation, which Tim cites, is that our government is not for sale. This is true for most major programs, such as social security. Voters have the dominant say.

But how about the details of smaller policies? Why aren’t the benefits of those redistributions exhausted by lobbying expenditures? My preferred explanation involves competition. In principle, more than one coalition is capable of winning a political game. If your winning coalition demands too high a bribe from interest groups, you will be undercut by another coalition able to deliver the policy for less. Government is not a unitary agent. This also helps explain, by the way, why democracy is stable rather than wracked by intransitive cycling. If you just write down different voting profiles, it appears any winning coalition can be outdone by another (at least for a multi-dimensional policy space). But if you add differential costs of organization to the mix, and make collecting the votes part of an explicit but imperfectly contestable market, you are much closer to getting a unique or near-unique outcome.

Ideas in this post are drawn from a paper by Roger Congleton and Bob Tollison. Here is a recent paper on the same topic.

Does Nation Building Work?

Nation-building Military Occupations by the

United States and Great Britain, 1850-2000

Payne, James. 2006. Does Nation Building Work? The Independent Review. 10 (4).

U.S. Occupations

Austria 1945-1955 success

Cuba 1898-1902 failure

Cuba 1906-1909 failure

Cuba 1917-1922 failure

Dominican Republic 1911-1924 failure

Dominican Republic 1965-1967 success

Grenada 1983-1985 success

Haiti 1915-1934 failure

Haiti 1994-1996 failure

Honduras 1924 failure

Italy 1943-1945 success

Japan 1945-1952 success

Lebanon 1958 failure

Lebanon 1982-1984 failure

Mexico 1914-1917 failure

Nicaragua 1909-1910 failure

Nicaragua 1912-1925 failure

Nicaragua 1926-1933 failure

Panama 1903-1933 failure

Panama 1989-1995 success

Philippines 1898-1946 success

Somalia 1992-1994 failure

South Korea 1945-1961 failure

West Germany 1945-1952 success

British Occupations

Botswana 1886-1966 success

Brunei 1888-1984 failure

Burma (Myanmar) 1885-1948 failure

Cyprus 1914-1960 failure

Egypt 1882-1922 failure

Fiji 1874-1970 success

Ghana 1886-1957 failure

Iraq 1917-1932 failure

Iraq 1941-1947 failure

Jordan 1921-1956 failure

Kenya 1894-1963 failure

Lesotho 1884-1966 failure

Malawi (Nyasaland) 1891-1964 failure

Malaysia 1909-1957 success

Maldives 1887-1976 success

Nigeria 1861-1960 failure

Palestine 1917-1948 failure

Sierra Leone 1885-1961 failure

Solomon Islands 1893-1978 success

South Yemen (Aden) 1934-1967 failure

Sudan 1899-1956 failure

Swaziland 1903-1968 failure

Tanzania 1920-1963 failure

Tonga 1900-1970 success

Uganda 1894-1962 failure

Zambia (N. Rhodesia) 1891-1964 failure

Zimbabwe (S. Rhodesia) 1888-1980 failure

How to fight corruption

Football referees in Nigeria can

take bribes from clubs but should not allow them to influence

their decisions on the pitch, a football official said on

Friday.Fanny Amun, acting Secretary-General of the Nigerian

Football Association, said bribery was common in the Nigerian

game."We know match officials are offered money or anything to

influence matches and they can accept it," Amun told Reuters on

Friday…"Referees should only pretend to fall for the bait, but make

sure the result doesn’t favour those offering the bribe," Amun

said.

Here is the full story, and thanks to David (not Tom) Williamson for the pointer.

An underlying tension in libertarianism

On the one hand, [Charles] Murray says he wants to liberate citizens

from the welfare state so they can live life however they choose.

On the other hand, by liberating citizens from the welfare state,

he hopes to force them back into lives of traditional bourgeois

virtue.

Read more here. Many Swedes, of course, consider themselves highly individualistic, precisely for this reason.

Thanks to www.politicaltheory.info for the pointer.

Transparency vs. generality

The cause of classical liberalism as a really existing possibility for

political reform has been harmed by bundling free markets with a ban on

transfers. This package deal has influenced people who think justice

requires transfers to eschew free markets. If we had spent the last

forty years hammering away at liberal fundamentals like transparency

and generality instead of the natural right to not be taxed, our

society would now be closer to the free market, limited government

ideal.

That is from Will Wilkinson, commenting on Asymmetrical Information. I am personally a bigger fan of transparency than generality, noting that the two often conflict. What if only some people need helping? The best policy response won’t be perfectly general, nor should we force it to be.

Many fiscal conservatives argue that Medicare should be a welfare program and not for all old people. If you wish to argue that it must be universal to be adequately funded, you are giving up on transparency but holding on to generality.

Will’s paragraph makes me wonder whether value of transparency is, or ever can be, transparent.

Economic costs and benefits of the Iraq War

I’ve read through the new Davis, Murphy, and Topel paper on the Iraq War. They conclude that if you account for the future dangers of a Saddam-led Iraq, the war might make sense in cost-benefit terms, and yes that does count dead Iraqis. Most of all, this paper takes seriously the costs of future containment efforts that might have been needed against Saddam.

This is serious work and it deserves more attention than it will likely receive at this point. On one side, I very much doubt their assumption that a Saddam-led Iraq "raises the probability of a major terrorist attack by 4 percentage points in any given year…" On the other side, perhaps the current civil war might have occurred, sooner or later, if we had stayed out. It is also hard to estimate the costs from skepticism about U.S. WMD intelligence the next time around. As you might expect, the most important variables are the most difficult to quantify. File this one under The Policy Will be Judged by its Absolute, Not Relative, Consequences.

Line-item vetoes won’t cut spending

Bush is asking for this authority, but it is unlikely to constrain spending. Read this (JSTOR) paper "Line-Item Veto: Where Is Thy Sting?". Excerpt: "Curiously, there exists little empirical support for the presumption that item-veto authority is important."

Or here is Robert Reischauer:

The crux of my message is that the item veto would have little effect on total spending and the deficit. I will buttress this conclusion by making three points. First, since the veto would apply only to discretionary spending, its potential usefulness in reducing the deficit or controlling spending is necessarily limited. Second, evidence from studies of the states’ use of the item veto indicates that it has not resulted in decreased spending; state governors have instead used it to shift states’ spending priorities. Third, a Presidential item veto would probably have little or no effect on overall discretionary spending, but it could substitute Presidential priorities for Congressional ones [TC: Hmm…].

Reischauer cites work by Douglas Holtz-Eakin:

Governors in 43 states [circa 1992] have the power to remove or reduce particular items that are enacted by state legislatures. The evidence from studies of the use of the item veto by the states, however, indicates no support for the assertion that it has been used to reduce state spending.

I have one simple model in mind: the legislature comes up with more individual pieces of pork in the first place. Can you think of others?

Rwandan killers, again

There were two kinds of rapists. Some took the girls and used them as wives until the end, even on the flight to Congo; they took advantage of the situation to sleep with prettified Tutsis and in exchange showed them a little bit of consideration. Others caught them just to fool around with, for having sex and drinking; they raped for a little while and then handed them over to be killed right afterward. There were no orders from the authorities. The two kinds were free to do as they pleased.

Of course a great number didn’t do that, had no taste for it or respect for such misbehaving. Most said it was not proper, to mix together fooling around and killing.

That is from Jean Hatzfeld’s Machete Season: The Killers in Rwanda Speak. Here is my previous post about the book.

Rwandan killers speak

During that killing season we rose earlier than usual to eat lots of meat, and we went up to the soccer field at around nine or ten o’clock. The leaders would grumble about latecomers, and we would go off on the attack. Rule number one was to kill. There was no rule number two. It was an organization without complications.

That is from Jean Hatzfeld’s Machete Season: The Killers in Rwanda Speak. I will post more about this remarkable book soon. Here is one good review of the book.

Are stationary bandits better?

I once wrote:

Some time ago, [Mancur] Olson started work on the fruitful distinction between a stationary and a roving bandit. A stationary bandit has some incentive to invest in improvements, because he will reap some return from those improvements. A roving bandit will confiscate wealth with little regard for the future. Olson then used this distinction to help explain the evolution of dictatorship in the twentieth century, and going back some bit in time, the rise of Western capitalism.

I have never found this approach fully convincing. Is the stationary bandit really so much better than the roving bandit? Much of Olson’s argument assumes that the stationary bandit is akin to a profit-maximizer. In reality, stationary bandits, such as Stalin and Mao, may have been maximizing personal power or perhaps something even more idiosyncratic. Second, the stationary bandit might be keener to keep control over the population, given how much is at stake. He may oppose liberalization more vehemently, for fear that a wealthier and freer society will overthrow him.

Here is more. I had forgotten I had written that review, so I must thank Arnold Kling for the pointer.

Who will guard the guardians?

From Cory Doctorow at Boing Boing Blog:

A CBS undercover reporting team went into 38 police stations in Miami-Dade and

Broward Counties in Florida, asking for a set of forms they could use to

complain about inappropriate police behavior. In all but three of the stations,

the police refused to give them forms. Some of the cops threatened them (on

hidden camera, no less) — one of them even touched his gun.officer: Where do you live? Where do you live? You have to tell me

where you live, what your name is, or anything like that.tester: For a complaint? I mean, like, if I have —

officer: Are you on medications?

tester: Why would you ask me something like that?

officer: Because you’re not answering any of my questions.

tester: Am I on medications?

officer: I asked you. It’s a free country. I can ask you that.

tester: Okay, you’re right.

officer: So you’re not going to tell me who you are, you’re not going to tell

me what the problem is.You’re not going to identify yourself.tester: All I asked you was, like, how do I contact —

officer: You said you have a complaint. You say my officers are acting in an

inappropriate manner.officer: So leave now. Leave now. Leave now.

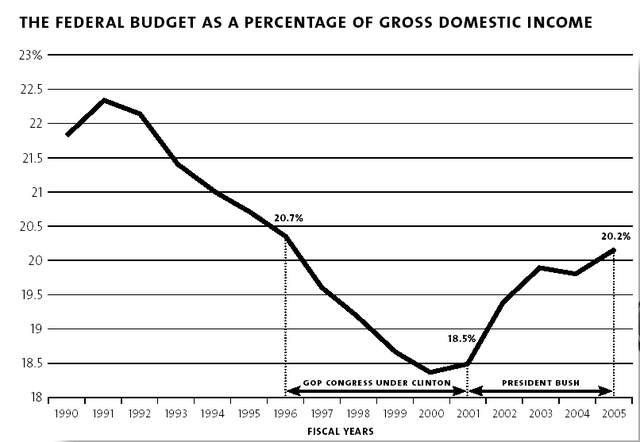

Bush the Impostor

George W. Bush is widely considered one of the most conservative

presidents in history. His invasion of Iraq, his huge tax cuts, and his

intervention in the Terri Schiavo case are among the issues on which

people on the left view him as being to the right of Attila the Hun.

But those on the right have a different perspective–mostly discussed

among themselves or in forums that fly below the major media’s radar.

They know that Bush has never really been one of them the way Ronald

Reagan was. Bush is more like Richard Nixon–a man who used the right to

pursue his agenda but was never really part of it. In short, he is an

impostor…

That’s Bruce Bartlett making his case in a Cato Policy Report and don’t miss his book, Impostor. See also Stephen Slivinski’s report How Republicans became defenders of Big Government in the Milken Review.

Finally in related news, the leading contender for Bush’s Presidential library, Southern Methodist University, seized the needed land using eminent domain.

Addendum: Donald Coffin and Marty O’Brien point out that the article in the New York Sun linked above is misleading, there is a lawsuit contending that SMU is using nefarious shenanigans to get some land for the library but, since SMU is a private entity, eminent domain is not involved. Virginia Postrel has a better write-up on the situation.

Do competitive House seats make for ideologues?

It has been suggested that congressional polarization is exacerbated by new districting arrangements that make each House seat safe for either a Democratic or a Republican incumbent. If only these seats were truly competitive, it is said, more centrist legislators would be elected. That seems plausible, but David C. King of Harvard has shown that it is wrong: in the House, the more competitive the district, the more extreme the views of the winner. This odd finding is apparently the consequence of a nomination process dominated by party activists. In primary races, where turnout is low (and seems to be getting lower), the ideologically motivated tend to exercise a preponderance of influence.

Thanks to Eric Rasmusen for the pointer, comments are open. The implication, of course, is that electoral competition is overrated. If we think of more moderate outcomes as better on average (debatable, admittedly), we can view the problem of politics in a new way. Do aggregation mechanisms produce better decisions when individuals feel that less is on the line? Is this the opposite of everything we learned from Anthony Downs?