Category: Political Science

U.S. interventions in the New World, with leader removal

I can think of a few. I am not thinking of ongoing struggles, such as the funding of opposition to the Sandinistas, rather I wish to focus on cases where the key leaders actually were removed. After all, we know that is the case in Venezuela today. Maybe these efforts were rights violations, or unconstitutional, and yes that matters. But how did they fare in utilitarian terms?

Puerto Rico: 1898, a big success.

Mexican-American War: Removed Mexican leaders from what today is the American Southwest. Big utilitarian success, including for the many Mexicans who live there now.

Chile, and the coup against Allende: A utilitarian success, Chile is one of the wealthiest places in Latin America and a stable democracy today.

Grenada: Under Reagan, better than Marxism, not a huge success, but certainly an improvement.

Panama, under the first Bush, or for that matter much earlier to get the Canal built: Both times a big success.

Haiti, under Clinton, and also 1915-1934: Unclear what the counterfactuals should be, still this case has to be considered a terrible failure.

Cuba, 1906-1909: Unclear? Nor do I know enough to assess the counterfactual.

Dominican Republic, 1961-1954, starting with Trujillo. A success, as today the DR is one of the wealthiest countries in Latin America. But the positive developments took a long time.

I do not know enough about the U.S. occupation of the DR 1916-1924 to judge that instance. But not an obvious success?

Can we count the American Revolution itself? The Civil War? Both I would say were successes.

We played partial but perhaps non-decisive roles in regime changes in Ecuador 1963 and Brazil 1964, in any case I consider those results to be unclear. Maybe Nicaragua 1909-1933 counts here as well.

So the utilitarian in you, at least, should be happy about Venezuela, whether or not you should be happy on net.

You should note two things. First, the Latin interventions on the whole have gone much better than the Middle East interventions. Perhaps that is because the region has stronger ties to democracy, and also is closer to the United States, both geographically and culturally. Second, looking only at the successes, often they took a long time and/or were not exactly the exact kinds of successes the intervenors may have sought.

Absher, Grier, and Grier consider CIA activism in Latin America and find poor results. I think much of that is springing from cases where we failed to remove the actual leaders, such as Nicaragua and Cuba. Simply funding a conflict does seem to yield poor returns.

Why Some US Indian Reservations Prosper While Others Struggle

Our colleague Thomas Stratmann writes about the political economy of Indian reservations in his excellent Substack Rules and Results.

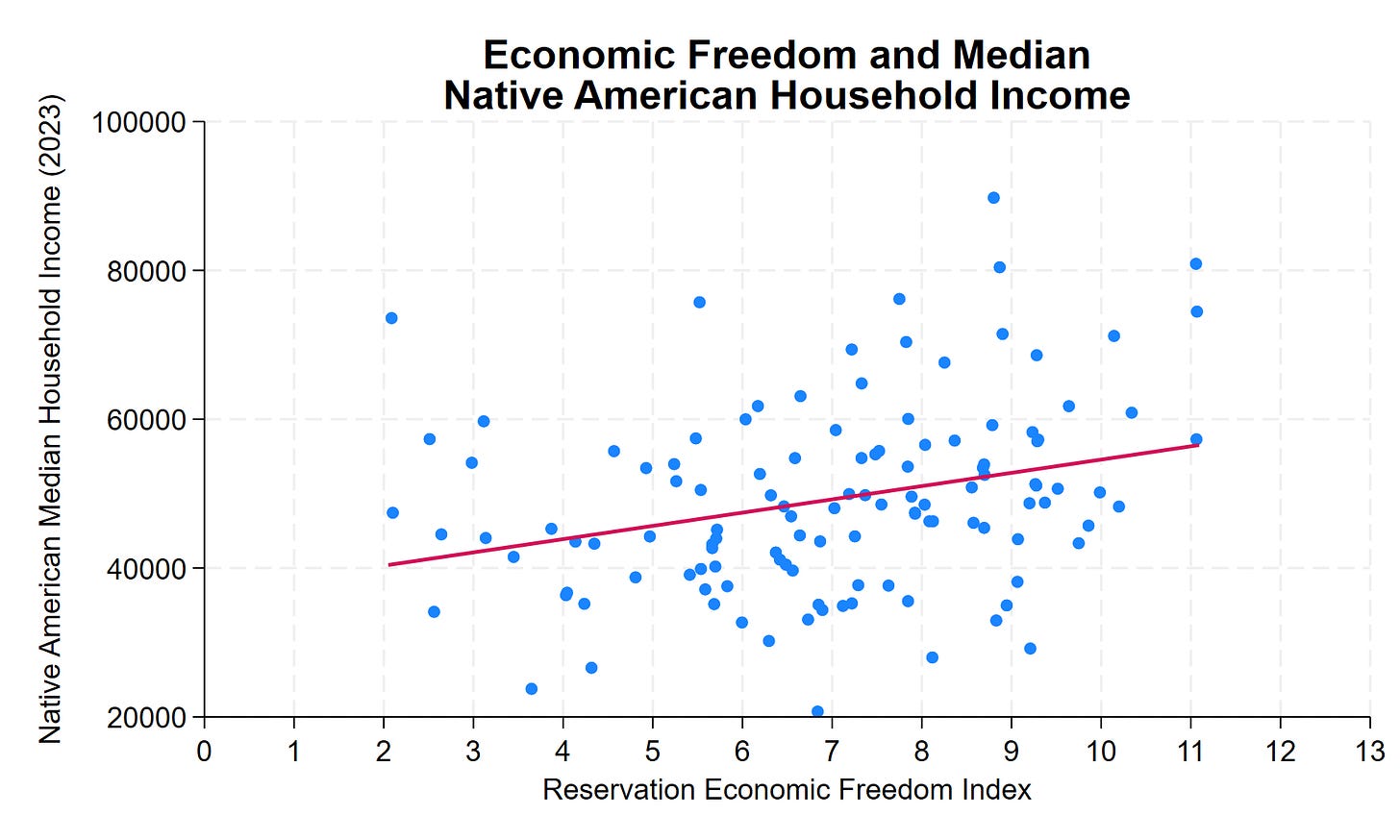

Across 123 tribal nations in the lower 48 states, median household income for Native American residents ranges from roughly $20,000 to over $130,000—a sixfold difference. Some reservations have household incomes comparable to middle-class America. Others face persistent poverty.

Why?

The common assumption: casino revenue. The data show otherwise. Gaming, natural resources, and location explain some variation. But they don’t explain most of it. What does? Institutional quality.

The Reservation Economic Freedom Index 2.0 measures how property rights, regulatory clarity, governance, and economic freedom vary across tribal nations. The correlation with prosperity is clear, consistent, and statistically significant. A 1-point improvement in REFI—on a 0-to-13 scale—correlates with approximately $1,800 higher median household income. A 10-point improvement? Nearly $18,000 more per household.

Many low-REFI features aren’t tribal choices—they’re federal impositions. Trust status prevents land from being used as collateral. Overlapping federal-state-tribal jurisdiction creates regulatory uncertainty. BIA approval requirements add months or years to routine transactions. Complex jurisdictional frameworks can deter investment when the rules governing business activity, dispute resolution, and enforcement remain unclear.

This is an important research program. In addition to potentially improving the lives of native Americans, the 123 tribal nations are a new and interesting dataset to study institutions.

See the post for more details amd discussion of causality. A longer paper is here.

California facts of the day

At Berkeley, as recently as 2015, white male hires were 52.7 percent of new tenure-track faculty; in 2023, they were 21.5 percent. UC Irvine has hired 64 tenure-track assistant professors in the humanities and social sciences since 2020. Just three (4.7 percent) are white men. Of the 59 Assistant Professors in Arts, Humanities and Social Science appointed at UC Santa Cruz between 2020-2024, only two were white men (3 percent).

Here is the essay by Jacob Savage that everyone is talking about.

What should I ask Joanne Paul?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with her. From the Google internet:

Joanne Paul is a writer, broadcaster, consultant, and Honorary Senior Lecturer in Intellectual History at the University of Sussex. A BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinker, her research focuses on the intellectual and cultural history of the Renaissance and Early Modern periods…

She has a new book out Thomas More: A Life.

Here is her home page. Here is Joanne on Twitter. She has many videos on the Tudor period, some with over one million views.

So what should I ask her?

Art as Data in Political History

From Valentine Figuroa of MIT:

Ongoing advances in machine learning are expanding opportunities to analyze large-scale visual data. In historical political economy, paintings from museums and private collections represent an untapped source of information. Before computational methods can be applied, however, it is essential to establish a framework for assessing what information paintings encode and under what assumptions it can be interpreted. This article develops such a framework, drawing on the enduring concerns of the traditional humanities. I describe three applications using a database of 25,000 European paintings from 1000CE to the First World War. Each application targets a distinct type of information conveyed in paintings (depicted content, communicative intent, and incidental information) and a cultural transformation of the early-modern period. The first revisits the notion of a European “civilizing process”—the internalization of stricter norms of behavior that occurred in tandem with the growth of state power—by examining whether paintings of meals show increasingly complex etiquette. The second analyzes portraits to study how political elites shaped their public image, highlighting a long-term shift from chivalric to more rational-bureaucratic representations of men. The third documents a long-term process of secularization, measured by the share of religious paintings, which began prior to the Reformation and accelerated afterward.

Here is the link, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Building a cohesive Indonesia

Building a cohesive nation-state amid deep ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity is a central challenge for many governments. This paper examines the process of nation building, drawing lessons from the remarkable experience of Indonesia over the past century. I discuss conceptual perspectives on nation building and review Indonesia’s historical nation-building trajectory. I then synthesize insights from four studies exploring distinct policy interventions in Indonesia—population resettlement, administrative unit proliferation, land reform, and mass schooling—to understand their effects on social cohesion and national integration. Together, these cases underscore the promise and pitfalls of nation-building efforts in diverse societies, offering guidance for future research and policymaking to support these endeavors in Indonesia and beyond.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Samuel Bazzi. As I have noted in the past, Indonesia remains a remarkably understudied and also undervisited country (Bali aside), so efforts in this direction should be appreciated.

Origins and persistence of the Mafia in the United States

This paper provides evidence of the institutional continuity between the “old world” Sicilian mafia and the mafia in America. We examine the migration to the United States of mafiosi expelled from Sicily in the 1920s following Fascist repression lead by Cesare Mori, the so-called “Iron Prefect”. Using historical US administrative records and FBI reports from decades later, we provide evidence that expelled mafiosi settled in pre-existing Sicilian immigrant enclaves, contributing to the rise of the American La Cosa Nostra (LCN). Our analysis reveals that a significant share of future mafia leaders in the US originated from neighborhoods that had hosted immigrant communities originating in the 32 Sicilian municipalities targeted by anti-mafia Fascist raids decades earlier. Future mafia activity is also disproportionately concentrated in these same neighborhoods. We then explore the socio-economic impact of organized crime on these communities. In the short term, we observe increased violence in adjacent neighborhoods, heightened incarceration rates, and redlining practices that restricted access to the formal financial sector. However, in the long run, these same neighborhoods exhibited higher levels of education, employment, and social mobility, challenging prevailing narratives about the purely detrimental effects of organized crime. Our findings contribute to debates on the persistence of criminal organizations and their broader economic and social consequences.

That is a new paper in the works by Zachary Porreca, Paolo Pinotti, and Masismo Anelli, here is the abstract online.

Does studying economics and business make students more conservative?

College education is a key determinant of political attitudes in the United States and other countries. This paper highlights an important source of variation among college graduates: studying different academic fields has sizable effects on their political attitudes. Using surveys of about 300,000 students across 500 U.S. colleges, we find several results. First, relative to natural sciences, studying social sciences and humanities makes students more left-leaning, whereas studying economics and business makes them more right-leaning. Second, the rightward effects of economics and business are driven by positions on economic issues, whereas the leftward effects of humanities and social sciences are driven by cultural ones. Third, these effects extend to behavior: humanities and social sciences increase activism, while economics and business increase the emphasis on financial success. Fourth, the effects operate through academic content and teaching rather than socialization or earnings expectations. Finally, the implications are substantial. If all students majored in economics or business, the college–noncollege ideological gap would shrink by about one-third. A uniform-major scenario, in which everyone studies the same field, would reduce ideological variance and the gender gap. Together, the results show that academic fields shape students’ attitudes and that field specialization contributes to political fragmentation.

That is a recent paper from Yoav Goldstein and Matan Kolerman. Here is a thread on the paper.

Political Organization in Pre-Colonial Africa

We provide an overview of the explanations for the relative lack of state formation historically in Africa. In doing so we systematically document for the first time the extent to which Africa was politically decentralized, calculating that in 1880 there were probably 45,000 independent polities which were rarely organized on ethnic lines. At most 2% of these could be classified as states. [emphasis added by TC] We advance a new argument for this extreme political decentralization positing that African societies were deliberately organized to stop centralization emerging. In this they were successful. We point out some key aspects of African societies that helped them to manage this equilibrium. We also emphasize how the organization of the economy was subservient to these political goals.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Soeren J. Henn and James A. Robinson.

The EU production function

The central puzzle of the EU is its extraordinary productivity. Grand coalitions, like the government recently formed in Germany, typically produce paralysis. The EU’s governing coalition is even grander, spanning the center-right EPP, the Socialists, the Liberals, and often the Greens, yet between 2019 and 2024, the EU passed around 13,000 acts, about seven per day. The U.S. Congress, over the same period, produced roughly 3,500 pieces of legislation and 2,000 resolutions.1

Not only is the coalition broad, but encompasses huge national and regional diversity. In Brussels, the Parliament has 705 members from roughly 200 national parties. The Council represents 27 sovereign governments with conflicting interests. A law faces a double hurdle, where a qualified majority of member states and of members of parliament must support it. The system should produce gridlock, more still than the paralysis commonly associated with the American federal government. Yet it works fast and produces a lot, both good and bad. The reason lies in the incentives: every actor in the system is rewarded for producing legislation, and not for exercising their vetoes…

Formally, the EU is a multi-actor system with many veto points (Commission, Parliament, Council, national governments, etc.), which should require broad agreement and hence slow decision making. In practice, consensus is manufactured in advance rather than reached through deliberation.

By the time any proposal comes up for an official vote, most alternatives have been eliminated behind closed doors. A small team of rapporteurs agrees among themselves; the committee endorses their bargain; the plenary, in turn, ratifies the committee deal; and the Council Presidency, pressed for time, accepts the compromise (with both Council and Parliament influenced along the way by the Commission’s mediation and drafting). Each actor can thus claim a victory and no one’s incentive is to apply the brakes.

That is from an excellent piece by Luis Garicano. What would Buchanan and Tullock say?

Welcome to the Crazy CAFE

To let Americans buy smaller cars, Trump had to weaken fuel-efficiency standards. Does that sound crazy? Small cars, of course, have much higher fuel efficiency. Yet this is exactly how the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards work.

Since 2011, fuel-economy targets scale with a vehicle’s “footprint” (wheelbase × track width). Big vehicles get lenient targets; small vehicles face demanding ones. A microcar that gets 40 MPG might be judged against a target of 50-60 MPG, while a full-size truck doing 20 MPG can satisfy a 22 MPG requirement.. The small car is clearly more efficient, yet it fails the rule that the truck passes.

The policy was meant to be fair to producers of large vehicles, but it rewards bloat. Make a car bigger and compliance gets easier. Add crash standards built around heavier vehicles and it’s obvious why the US market produces crossovers and trucks while smaller and much less expensive city-cars, familiar in Europe and Asia, never show up. At a press conference rolling back CAFE standards, Trump noted he’d seen small “kei” cars on his Asia trip—”very small, really cute”—and directed the Transportation Secretary to clear regulatory barriers so they could be built and sold in America.

Trump’s rollback—cutting the projected 2031 fleet average from roughly 50.4 MPG to 34.5 MPG—relaxes the math enough that microcars could comply again. Only Kafka would appreciate a fuel-economy system that makes small fuel-efficient cars hard to sell and giant trucks easy. Yet the looser rules remove a barrier to greener vehicles while also handing a windfall to big truck makers. A little less Kafka, a little more Tullock.

Political pressure on the Fed

From a forthcoming paper by Thomas Drechsel:

This paper combines new data and a narrative approach to identify variation in political pressure on the Federal Reserve. From archival records, I build a data set of personal interactions between U.S. Presidents and Fed officials between 1933 and 2016. Since personal interactions do not necessarily reflect political pressure, I develop a narrative identification strategy based on President Nixon’s pressure on Fed Chair Burns. I exploit this narrative through restrictions on a structural vector autoregression that includes the President-Fed interaction data. I find that political pressure to ease monetary policy (i) increases the price level strongly and persistently, (ii) does not lead to positive effects on real economic activity, (iii) contributed to inflationary episodes outside of the Nixon era, and (iv) transmits differently from a typical monetary policy easing, by having a stronger effect on inflation expectations. Quantitatively, increasing political pressure by half as much as Nixon, for six months, raises the price level by about 7% over the following decade.

That is not entirely a positive omen for the current day.

My Conversation with the excellent Dan Wang

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Tyler and Dan debate whether American infrastructure is actually broken or just differently optimized, why health care spending should reach 35% of GDP, how lawyerly influences shaped East Asian development differently than China, China’s lack of a liberal tradition and why it won’t democratize like South Korea or Taiwan did, its economic dysfunction despite its manufacturing superstars, Chinese pragmatism and bureaucratic incentives, a 10-day itinerary for Yunnan, James C. Scott’s work on Zomia, whether Beijing or Shanghai is the better city, Liu Cixin and why volume one of The Three-Body Problem is the best, why contemporary Chinese music and film have declined under Xi, Chinese marriage markets and what it’s like to be elderly in China, the Dan Wang production function, why Stendhal is his favorite novelist and Rossini’s Comte Ory moves him, what Dan wants to learn next, whether LLMs will make Tyler’s hyper-specific podcast questions obsolete, what flavor of drama their conversation turned out to be, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: When will Chinese suburbs be really attractive?

WANG: What are Chinese suburbs? You use this term, Tyler, and I’m not sure what exactly they mean.

COWEN: You have a yard and a dog and a car, right?

WANG: Yes.

COWEN: You control your school district with the other parents. That’s a suburb.

WANG: How about never? I’m not expecting that China will have American-style suburbs anytime soon, in part because of the social engineering projects that are pretty extensive in China. I think there is a sense in which Chinese cities are not especially dense. Indian cities are much, much more dense. I think that Chinese cities, the streets are not necessarily terribly full of people all the time. They just sprawl quite extensively.

They sprawl in ways that I think the edges of the city still look somewhat like the center of the city, which there’s too many high-rises. There’s probably fewer parks. There’s probably fewer restaurants. Almost nobody has a yard and a dog in their home. That’s in part because the Communist Party has organized most people to live in apartment compounds in which it is much easier to control them.

We saw this really extensively in the pandemic, in which people were unable to leave their Shanghai apartment compounds for anything other than getting their noses and mouths swabbed. I write a little bit about how, if you take the rail outside of major cities like Beijing and Shanghai, you hit farmland really, really quickly. That is in part because the Communist Party assesses governors as well as mayors on their degree of food self-sufficiency.

Cities like Shanghai and Beijing have to produce a lot of their own crops, both grains as well as vegetables, as well as fruits, as well as livestock, within a certain radius so that in case there’s ever a major devastating war, they don’t have to rely on strawberries from Mexico or strawberries from Cambodia, or Thailand. There’s a lot of farmland allocated outside of major cities. I think that will prevent suburban sprawl. You can’t control people if they all have a yard as well as a dog. I think the Communist Party will not allow it.

COWEN: Whether the variable of engineers matters, I went and I looked at the history of other East Asian economies, which have done very well in manufacturing, built out generally excellent infrastructure. None of these problems with the Second Avenue line in New York. Taiwan, like the presidents, at least if we believe GPT-5, three of them were lawyers and none of them were engineers. South Korea, you have actually some economists, a lot of bureaucrats.

WANG: Wow. Imagine that. Economists in charge, Tyler.

COWEN: I wouldn’t think it could work. A few lawyers, one engineer. Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, he’s a lawyer. He thinks in a very lawyerly manner. Singapore has arguably done the best of all those countries. Much richer than China, inspired China. Why should I think engineers rather than just East Asia, and a bunch of other accompanying facts about these places are what matter?

WANG: Japan, a lot of lawyers in the top leadership. What exactly was the leadership of Hong Kong? A bunch of British civil servants.

COWEN: Some of whom are probably lawyers or legal-type minds, right? Not in general engineers.

WANG: PPE grads. I think that we can understand the engineering variable mostly because of how much more China has done relative to Japan and South Korea and Taiwan.

COWEN: It’s much, much poorer. Per capita manufacturing output is gone much better in these other countries.

And:

WANG: Tyler, what does it say about us that you and I have generally a lot of similar interests in terms of, let’s call it books, music, all sorts of things, but when it comes to particular categories of things, we oppose each other diametrically. I much prefer Anna Karenina to War and Peace. I prefer Buddenbrooks to Magic Mountain. Here again, you oppose me. What’s the deal?

COWEN: I don’t think the differences are that big. For instance, if we ask ourselves, what’s the relative ranking of Chengdu plus Chongqing compared to the rest of the world? We’re 98.5% in agreement compared to almost anyone else. When you get to the micro level, the so-called narcissism of petty differences, obviously, you’re born in China. I grew up in New Jersey. It’s going to shape our perspectives.

Anything in China, you have been there in a much more full-time way, and you speak and read Chinese, and none of that applies to me. I’m popping in and out as a tourist. Then, I think the differences make much more sense. It’s possible I would prefer to live in Shanghai for essentially the reasons you mentioned. If I’m somewhere for a week, I’m definitely going to pick Beijing. I’ll go around to the galleries. The things that are terrible about the city just don’t bother me that much, because I know I’ll be gone.

WANG: 98.5% agreement. I’ll take that, Tyler. It’s you and me against the rest of the world, but then we’ll save our best disagreements for each other.

COWEN: Let’s see if you can pass an intellectual Turing test. Why is it that I think Yunnan is the single best place in the world to visit? Just flat out the best if you had to pick one region. Not why you think it is, but why I think it is.

Strongly recommended, Dan and I had so much fun we kept going for about an hour and forty minutes. And of course you should buy and read Dan’s bestselling book Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future.

Congressional leadership is corrupt

Using transaction-level data on US congressional stock trades, we find that lawmakers who later ascend to leadership positions perform similarly to matched peers beforehand but outperform them by 47 percentage points annually after ascension. Leaders’ superior performance arises through two mechanisms. The political influence channel is reflected in higher returns when their party controls the chamber, sales of stocks preceding regulatory actions, and purchase of stocks whose firms receiving more government contracts and favorable party support on bills. The corporate access channel is reflected in stock trades that predict subsequent corporate news and greater returns on donor-owned or home-state firms.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Shang-Jin Wei and Yifan Zhou. Of course Alex T. has been on this issue for a long time now.

*Liberal Worlds: James Bryce and the Democratic Intellect*

By H.S. Jones, an excellent book. For all the resurgence of interest in government and its problems, Bryce has received remarkably little attention. But his theory of low-quality, careerist politcians, combined with imperfectly informed voters, seems highly relevant to our current day. Public opinion is slow, and largely reactive, but potent once mobilized. Leadership can truly matter, and he stresses national character and civic education. In other words, Bryce’s The American Commonwealth is a book still worth reading.

I had not known that Bryce was born in Belfast, or that he was so opposed to women’s suffrage. Or that he was so interested in Armenia, climbed Mount Ararat, and was fascinated by the inevitability of interracial marriage and its consequences (no, not in the usual racist way). He was an expert on Roman law.

Recommended, and also very well written.