Category: Political Science

Would Kerry be more fiscally irresponsible than Bush?

Virginia Postrel says yes; read more here. Paul Krugman suggests Kerry will repeal the tax cut [tax shift, more accurately] to spend more on health care, rather than trying to restore a balanced budget (my words, not his). Can these two luminaries, not always in total agreement, be wrong?

No doubt, if you look at what Kerry says, it sounds like he will spend more than Bush. But the ever-perceptive Jane Galt reminds us that, well…politicians are liars! (Just don’t let on you heard it here…)

I look less at what politicians say, and more at what kind of coalition they would have to build to rule. The high domestic spending of Bush I take as a sign of perceived political weakness (“we need to buy more allies”), rather than a reflection of Bush’s ideology. So in part it depends on what a Kerry victory would look like. But here are a few reasons to think Kerry might be more fiscally responsible:

1. The Republicans will still probably control the House and maybe the Senate too, check out the odds. The political benefits from spending are less, the less you control the content of that spending.

2. The Republicans become more fiscally conservative in opposition.

3. Kerry’s supporters hate Bush, most of all, for what is perceived to be his “Texan-evangelical-grammatically challenged-frat boy” symbolism [just for the record, I don’t buy this picture]. Kerry can appease his base on these symbols fairly easily, just by showing up for work. I doubt if many Kerry supporters are expecting or requiring that a Kerry candidacy would bring a significant movement toward the left on economic policy, above and beyond repealing some of the tax cuts. The left hates Bush so much they would become captives of the center, if Kerry held the presidency. The left would have nowhere else to go (advice to the left: be careful how much Bush hatred you show!)

4. Kerry would be under constant pressure to show that he is “tough” on foreign policy. This will limit his ability to make domestic spending commitments. And if he does well on foreign policy, and appears suitably in charge, he could get reelected without much using spending to buy domestic support. If he is weak on foreign policy, will lots of spending really help him?

5. If Bush is re-elected, it affirms that a Republican can get away with jacking up domestic spending. Such a precedent is worrying for the longer run, not just for Bush’s second term.

6. Have many Presidents moved closer toward their original ideological base in their second terms?

That’s enough raw unfounded speculation for one day. But no, it is not obvious to me that Kerry would be less fiscally responsible than Bush. It’s a judgment call, but let’s not obsess over what candidates say when campaigning. Don’t forget, it was Bush who campaigned on a platform of fiscal responsibility and no nation-building.

Weak arguments against privatization

Italy is planning to privatize many of its historic museums and buildings:

A portmanteau law affecting all aspects of the Italian artistic, built and environmental heritage was enacted last month. It is the product of three political tendencies. The first dates back to the late 1990s, when a Socialist government wanted to allow the private sector to become involved in a part of Italian life that for 50 years had been dominated by the State, in order to bring greater efficiency and better services to it. The second is the partial devolution of power to regional and local government as result of the electoral reforms of the 1990s, and the third proceeds from a 2001 Finance Act of the current, right wing government that aimed to raise money by the sale of public assets, including historic buildings and State-owned land.

This is a difficult policy issue, as national heritage can be a genuine public good. But the major argument being used against these privatizations is hardly convincing:

The proposal to sell State-owned buildings has been contentious, largely because the State does not know in detail what it owns [emphasis added], and the architectural protection lobbies are afraid that masterpieces may be sold to unsuitable owners.

Here is the full story.

Has Bush cut back government bureaucracy?

The following table lists how many of the major agencies or departments had their budgets cut in a given Presidential term:

President and Term, Number of Budget Cuts [see the last link in this post for further explanation of the data. I’ve done minor editing and added the boldface]

Johnson, 4 out 15

Nixon, 3 out 15

Carter, 5 out 15

Reagan 1, 8 out 15

Reagan 2, 10 out 15

Bush, George H., 2 out 15

Clinton 1, 9 out 15

Clinton 2, 0 out 15

Bush, George W., 0 out 15

Obviously Reagan II made real efforts in this direction. George W. comes in tied for last with Clinton II. This is a highly imperfect proxy, but when you are 0 for 15 it is hard to blame measurement error alone.

Here is one unnoticed achievement of Ronald Reagan:

President Reagan is the only president to have cut the budget of the Department of Housing and Urban Development in one of his terms (a total of 40.1 percent during his second term).

Here is the full and sad story on Bush’s fiscal policy for the agencies and departments. Here are the underlying data.

Why are people conservatives or liberals?

I’ve long suspected that many political debates boil down to a relatively small number dimensions or core value judgments. And I believe these values often are rooted in basic personality.

George Lakoff tries to put some meat on these bones. In a nutshell, he sees conservatives as siding with a “Strict Father” model, and liberals as siding with a “Nurturant Mother” model.

Lakoff writes:

My findings indicate that the family and morality are central to both worldviews…What we have here are two different forms of family-based morality. What links them to politics is a common understanding of the nation as a family, with the government as parent. Thus, it is natural for liberals to see it as the function of the government to help people in need and hence to support social programs, while it is equally natural for conservatives to see the function of the government as requiring citizens to be self-disciplined and self-reliant and, therefore, to help themselves.

The linked essay presents the hypothesis in more detail. For more detail, buy Lakoff’s fascinating book, Moral Politics. Note, however, that he definitely sides with the liberal point of view. I would argue, in contrast, that liberals misapply what is good family policy to larger polities, where a stricter and more impersonal approach is appropriate.

My take: I’ve never met an intelligent person who couldn’t come up at least five good objections to Lakoff’s thesis. But Lakoff’s writings make more progress on a difficult topic than anything else I have read to date. They also explain, in my view, why libertarianism, in practice usually ends up closer to the right wing than to the left. “Individual responsibility” is a core moral intuition for most libertarians, and this puts them closer to conservatives, despite the considerable differences.

That all being said, let’s say you realized that your political views followed from your core personality. Let’s say also that personality is something that, in large part, you do not choose. Either you are born with it, or your upbringing shapes you from an early age. Shouldn’t that make you less rather than more confident of your political views? After all, it would be a mere genetic accident that conservative or liberal politics should feel as right to you as they do.

Christians discover Tiebout

Would you like to live in a Christian nation with government similar to the early United States?

No, it’s not Colonial House (much inferior to Victorian House, by the way) but Christian Exodus

ChristianExodus.org has been established to coordinate the move of 50,000 or more Christians to a single conservative state in the U.S. for the express purpose of reestablishing constitutional governance….ChristianExodus.org is orchestrating the move of 50,000 or more Christians to one of three States for the express purpose of dissolving that State’s bond with the union. The three States under consideration are Alabama, Mississippi and South Carolina. The exact destination will be chosen by vote of our membership. Our move will commence when the federal government forces sodomite marriages on our local communities or once we reach the 50,000-member mark, whichever comes first.

If this sounds kinda familiar you may recall the libertarian Free State Project “an effort to recruit 20,000 liberty-loving people to move to New Hampshire.”

Cognitive Liberty

Freedom of thought is the most fundamental right. Fortunately, it has been nearly impossible to invade the mind. New technologies, however, do threaten freedom of thought, raising many difficult problems. Should children diagnosed with ADHD who refuse to take Ritalin be refused an education? Should a mentally-ill person be drugged so that they can stand trial? Is hypersonic advertising an invasion of mental privacy?

Here’s an interesting interview on these and related issues with Richard Glen Boire co-founder of the Center for Cognitive Liberty and Ethics.

Indian voters reject high-tech

India appears to take a turn for the worse:

The government in Andhra Pradesh state, headed by the coalition’s second-largest member and a leading proponent of India’s technology revolution, was routed by the Congress party, which is also the main opposition on the national stage.

Besides signalling that high-tech prowess had not impressed the millions of rural poor, the result suggested the national election could end in a hung parliament and likely political turmoil as parties searched for new allies.

Votes from the marathon national election will be counted on Thursday but financial markets have already tumbled on fears that India’s crucial economic reforms could be delayed if a weak government comes to power.

Here is the full story.

Let us not forget that India remains a badly messed-up economy. I found the following passage, from William Lewis’s The Power of Productivity, illuminating:

…India has a special problem. It is not clear who owns land in India. Over 90 percent of land titles are unclear…Unclear land titles most affect industries which use a lot of land. These industries are housing construction and retailing. The result is that there is huge demand for the very little land with clear titles. Not surprisingly, the ratio of land costs to per capita income in New Delhi and Bombay is ten times that ratio in the other major cities of Asia…Also not surprisingly, India has very few supermarkets and large-scale single-family housing developments.

But it gets worse: Stamp taxes on land sales run at least ten percent. Furthermore you are often expected to pay real estate taxes, even if you will never be granted title to the actual land. It is said that the money is accepted “without prejudice.” Here is a short article on how to make things better.

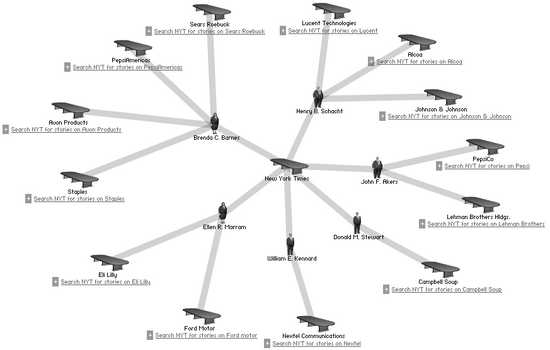

Map the Power Elite

They Rule is a very cool website that uses flash player as a front-end to a database on corporate boards. Find out who is on the board of any of the largest publicly held corporations, choose two firms and find the connections between their boards (ala six degrees of separation), map the power-elites. The map below (click to expand) gives an idea of what the site is all about.

The author, Josh On, is an odd-mix of old-style lefty and cutting edge technologist. When he’s not putting together websites like this what does he do?

Twice a week I stand outside on a street corner and try to engage strangers in conversations about politics. This would be much harder without a copy of Socialist Worker in my hand.

Hat tip to Boing Boing Blog.

Secession

Recently Killington voted to secede from Vermont and join New Hampshire. Some people find this desire quixotic since Killington is smack dab in the middle of Vermont. The classic Tiebout argument says that voting with one’s feet helps to discipline government and provide a better match between government and citizen preferences. But why should the dissidents have to pack their bags? It’s the Vermont taxes that the residents of Killington want to escape not the skiing. Wouldn’t it be less costly to switch governance rather than citizens?

Does such a system sound crazy? Perhaps, but it is essentially the same supra-competitive federalism that has worked well for corporate law, so maybe we ought to give it a try.

And remember, if at first you don’t secede, try, try again.

Why isn’t Brazil a first-world country?

I love Brazil, and there are few places where I feel more at home. That being said, the place can be a mess. Here is one reason why:

Unlike the United States, Brazil has chosen to collect most of its taxes through corporations. Thus today, taxes paid by corporations in Brazil are almost twice as high as in the United States. However, that’s not the right comparison. We should be making a comparison with the United States in 1913. That’s when the United States had the same GDP per capita as Brazil today. In 1913 the U.S. government spent only 8 percent of GDP. Thus, as a percentage of GDP, the corporate tax burden in Brazil today is seven times that of U.S. Corporations when the United States was at Brazil’s current GDP per capita.

Here are formal details on Brazilian corporate taxation. But the document does not stress the reality that half the firms shirk their burden and the more efficient firms must pay far more than they ought to.

It gets worse:

Brazil’s government spends about 11 percent of GDP on the government-run pension system compared with 5 percent in the United States today and close to zero in 1913. The government contribution to the pensions of Brazil’s government employees is 4.7 percent of GDP compared with 1.8 in the United States today….Brazil clearly has government employment it can’t afford.

Here is an article on Lula’s partial success in reforming Brazilian pensions, here is more detail.

The quotations are taken from William Lewis’s interesting The Power of Productivity.

To be continued…

What makes for media bias?

Economists are taking a greater interest in the media. Here is an interesting new paper by Andrei Shleifer and Sendhil Mullainathan, The Market for News .

Abstract: We investigate the market for news under two assumptions: that readers hold beliefs that they like to see confirmed, and that newspapers can slant stories toward these beliefs. We show that, on the topics where readers share common beliefs, one should not expect accuracy even from competitive media: competition results in lower prices, but common slanting toward reader biases. However, on topics where reader beliefs diverge (such as politically divisive issues), newspapers segment the market and slant toward the biases of their own audiences, yet in the aggregate a conscientious reader could get an unbiased perspective. Generally speaking, reader heterogeneity is more important for accuracy in media than competition per se.

Also read Alex’s earlier post, Surprise! Fox News is Fair and Balanced!.

War Politics

In 1995 the most prestigious journal in economics, the American Economic Review, published one of the most controversial papers in its long history, War Politics: An Economic, Rational-Voter Framework (JSTOR). Gregory Hess and Athanasios Orphanides modeled voters as caring about two presidential abilities, the ability to make war and the ability to manage the economy. To get reelected an incumbent President must convince voters that his combined abilities make him better than a challenger.

This simple model has some profound implications. If the economy is doing well, the President is up on one score and without evidence can be assumed to be as good as the challenger in war-making ability. Thus, the President gets reelected. But if the economy is doing badly then an incumbent who cannot present evidence that he is of superior war-making ability will lose for certain. Crucially, an incumbent can’t demonstrate war-making ability without a war – thus when the economy is doing poorly and the President is up for reelection the model predicts more wars.

Hess and Orphanides define a war as “an international crisis in which the United States is involved in direct military activity that results in violence.” Using data from the International Crisis Behavior Project they compare the onset of wars in first terms when there is a recession with the onset of wars in first terms with no recession and second terms. If wars are random these probabilities ought to be the same. Stunningly, however, they find that in the 1953-1988 period wars are about twice as likely in first terms with a recession than in first terms with no recession and second terms (60 percent to 30 percent). The probability of this result occurring by chance is about 5%. Various extensions and modifications produce similar results.

Need I mention that the Hess and Orphanides model has proven to have predictive power?

The stock market prices presidential candidates

…[political] platforms are capitalized into equity prices: under a Bush administration, relative to a counterfactual Gore administration, Bush-favored firms are worth 3-8 percent more and Gore-favored firms are worth 6-10 percent less. The most sensitive sectors include tobacco, worth 13-25 percent more under a favorable Bush administration, Microsoft competitors, worth 15 percent less under a favorable Bush administration, and alternative energy companies, worth 16-27 percent less under an unfavorable Bush administration.

This result was generated by correlating firm-specific equity returns with the Iowa Electronic [Presidential] Market forecasts. In other words, when Bush’s electoral fortunes went up, “Bush stocks” rose as well.

Here is the full paper. Here is the home page of the researcher, Brian Knight.

The bottom lines: 1) Overall the market did regard Bush as “better for business” than Gore. 2) Equity markets moved more rapidly than did the Iowa markets. 3) If the outcome of a Presidential election truly matters to you, your position can be hedged fairly easily. 4) Presumably there are “John Kerry stocks” right now.

Thanks to Eric Crampton for the pointer.

Phrase of the day

“The non-governmental sector.” At yesterday’s UNESCO meetings, I heard it at least fifteen times.

Yes I know the term has a (supposedly) legitimate use, but you will never hear it from my lips. How about a sentence like this?:

…non-governmental organizations have made and are increasingly making important contributions to both population and development activities at all levels. In many areas of population and development activities, non-governmental groups are already rightly recognized for their comparative advantage in relation to government agencies.

It’s nice to know that we are good for something!

The bottom line: Tomorrow I fly home.

Electronic voting

Many people fear electronic voting. What if there is an error? Don’t we need a paper trial? How can we be sure that the election won’t be stolen? My response is simple. Ever buy gas? When you buy gas do you pay cash or use a credit card? And when the terminal offers to print you a receipt do you take it, save it, and check it against your monthly Visa bill? Or do you press “no receipt” and drive away?

I have never once checked a gas receipt against my monthly credit card bill and I suspect most people don’t either. The credit card companies have big incentives to record transactions quickly and accurately. The system isn’t perfect but it’s good enough so that I don’t worry about being ripped off and, the key point, the electronic system is certainly more accurate than the primitive process of counting out paper and metallic tokens and handing them over to a minimum-wage cashier who repeats the process by counting out change. I see no reason why electronic voting should not be far superior to punch cards or other manual machine.

Obviously, we need to be careful, which brings me to a suggestion. How about open-source software for voting machines? Opening the source makes life easier for outsider hackers but harder for inside-hackers and open source is less-susceptible to bugs. Open-source would also be well, open – as in an open society.

I would say turn this project over to Linus Torvalds but he’s a Finn and we have to be careful about them but surely there are some skilled programmers who would like to lay the core for voting in the twenty-first century?

Addendum: Yup, here is an open-source voting project.