Directed Innovation in the Artificial Limb Industry

Innovation responds to both demand and supply. New scientific discoveries can arise exogenously and lower the cost of some types of innovation. Innovation, however, also responds to demand. The patenting of new energy devices increases as the price of oil increases. Similarly, new pharmaceuticals to treat diseases of old age increase as the number of elderly increase.

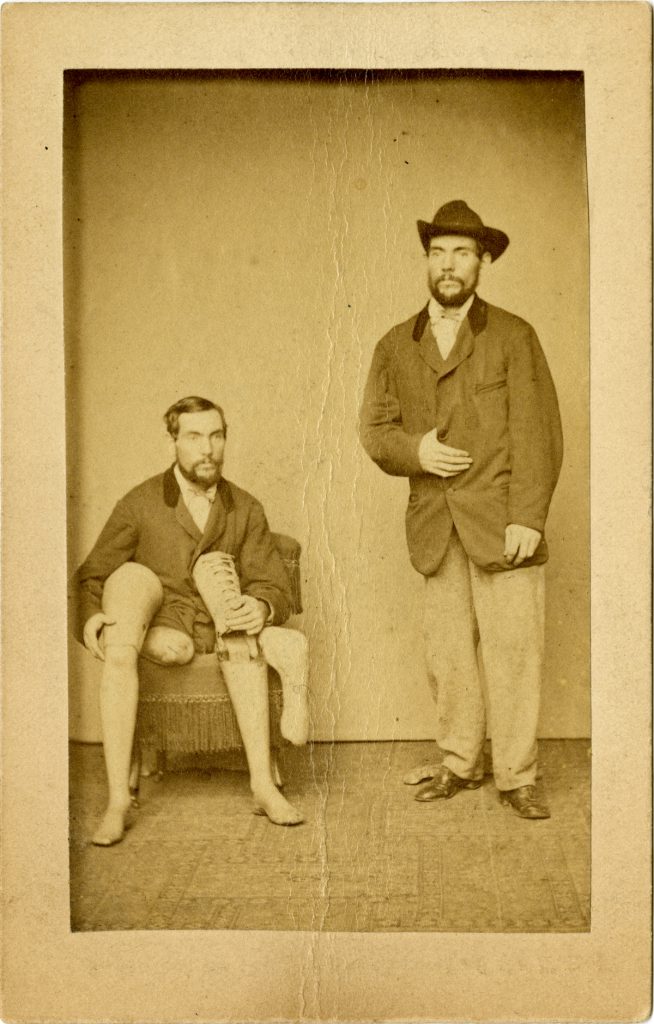

Similarly, the Civil War and World War I created a boom in the demand for artificial limbs and that in turn created a boom in innovation that led to better artificial limbs. The demand for new prosthetics was in some cases personal, as MacRae writes:

…the person who launched the era of modern prosthetics was also the first documented amputee of the Civil War–Confederate soldier James Edward Hanger. Hanger, who lost his leg above the knee to a cannon ball, was first fitted with a wooden peg leg by Yankee surgeons. Unhappy with the cumbersome appendage, Hanger eventually designed and built a new, lightweight leg from whittled barrel staves. Hanger’s innovative leg had hinges at the knee and foot, which helped him to sit more comfortably and to walk with a more natural gait. Hangar won the contract to make limbs for Confederate veterans. The company he founded–Hanger, Inc.–remains a key player in prosthetics and orthotics today.

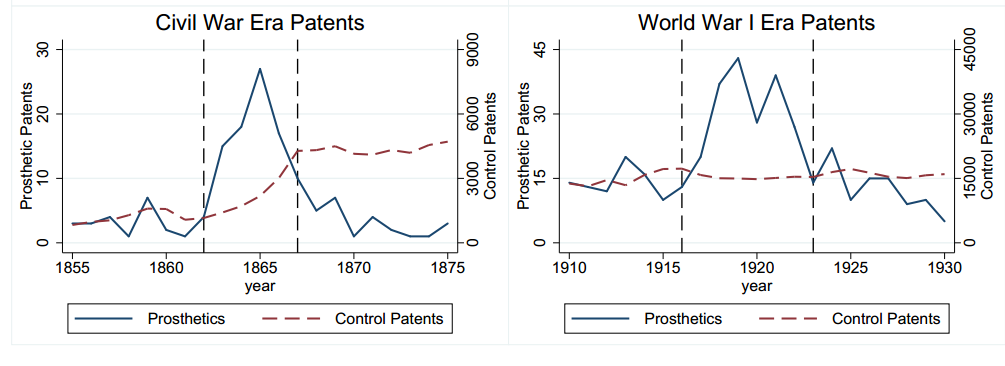

In a highly original paper, Jeffrey Clemens and Parker Rogers document the increase in patents during the war eras but they also show that the type of innovation not just the quantity also responded to economic incentives.

In the Civil War era, the quantity of limbs demanded increased but the government was quite stingy in paying for artificial limbs. As a result, innovators focused on process innovations that enabled the production of more limbs at lower cost. In contrast, WWI payments were more generous and the government emphasized reintegrated soldiers into society which made appearance a more dominant feature in limb patenting.

In the Civil War era, the quantity of limbs demanded increased but the government was quite stingy in paying for artificial limbs. As a result, innovators focused on process innovations that enabled the production of more limbs at lower cost. In contrast, WWI payments were more generous and the government emphasized reintegrated soldiers into society which made appearance a more dominant feature in limb patenting.

More generally, Clemens and Rogers show how the type of procurement contracts directs not just the quantity but the form of innovation. The lessons are relevant for modern health care costs. Many people, for example, have wondered why innovation tends to lower costs in most fields but raise costs in health care. Clemens and Rogers point to the nature of procurement contracts as a possible important influence.