Month: January 2023

Alas, Bennett McCallum has passed away

He was a great monetary and macro economist, and among his many achievements he was a pioneer of ngdp targeting ideas…RIP…

Does Angi Recommend Occupational Licensing?

Peter Blair and Mischa Fisher have a clever new paper on occupational licensing that uses data on millions of leads generated by Angi’s HomeAdivsor. Consumers on HomeAdvisor search for services, the platform knows whether the service requires a license in the consumer’s state and attempts to match the consumer with an appropriate local provider, the local provider can then choose whether to accept or reject the lead. If a lead is accepted, the consumer and provider then negotiate on the price and services–as the negotiation is mostly handled offline, the main measure of interest is the probability a lead is accepted.

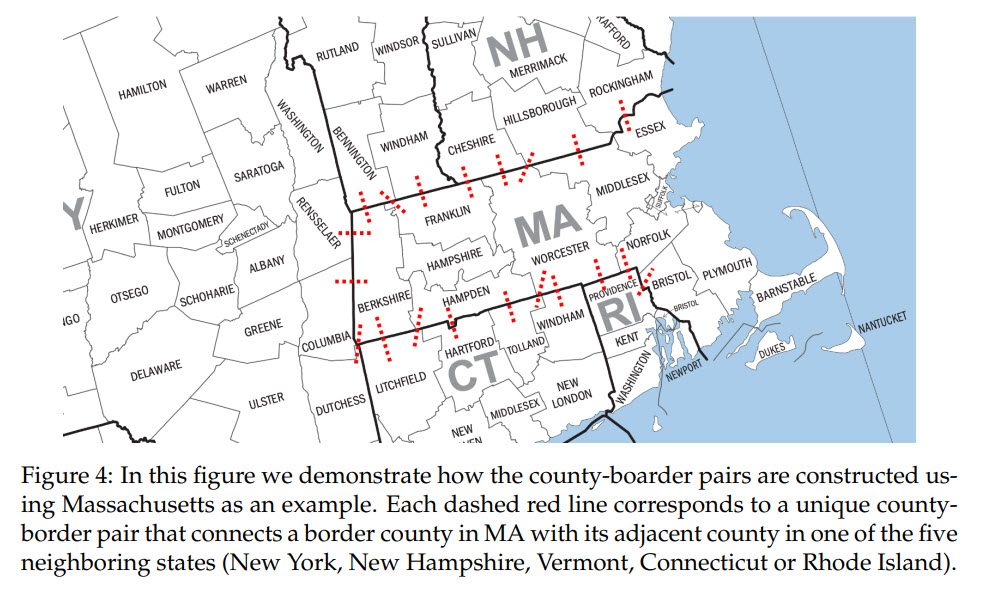

Many occupations are licensed in one state but not in another (as I pointed out in my talk on occupational licensing to the Heritage Foundation this is odd if you think there are strong arguments for occupational licensing on safety or quality grounds). Thus the authors compare the accepted lead rate in states that require a license to complete a task to the rate in states where the same task is unlicensed. To better control for other factors, the authors only compare the accepted lead rate in counties that border different states, as shown below. The authors also control for state, month and task fixed effects.

The bottom line is that the accepted lead rate is 12.3 percentage points or 21% lower in a county/state that license an occupation/task compared to a similar county/state where the task is unlicensed. In other words, if you live in a state that requires a license to complete a task it’s considerable more difficult to find a contractor than if you lived in nearby state that does not license the task.

Not surprisingly, the authors find that the accept rate declines not because there is a surge in demand for the licensed service but because supply declines when there are fewer licensed providers. In the long run, we also know that prices rise in licensed industries (e.g. my paper with Pizzola on licensing in the funeral services industry).

The authors combine their cross-sectional study with an event study that shows that after New Jersey required a license for pool contractors it become more difficult to find a pool contractor in New Jersey relative to other states.

The authors conclude:

The existing literature on licensing on digital platforms, which consists of three other papers, has carefully measured the impact of licensing on consumer satisfaction and safety by demonstrating that customer self-reports of service quality and objective platform measures of service provider safety do not increase in the presence of licensed service providers, despite the positive impact of licensing on prices (Hall et al., 2019; Farronato et al., 2020; Deyo, 2022).

…Taken together, our findings and those from the three others papers studying licensing in digital labor markets indicate that the traditional view of licensing espoused in Friedman (1962) about licensing in offline markets, i.e, licensing is a labor market restriction with limited benefits, also holds in digital labor markets (Hall et al., 2019; Farronato et al., 2020; Deyo, 2022). Our work provides a clear example where labor market regulations developed to govern the analogy economy work against the efficiency gains that technological innovation promises to bring in a digital economy (Goldfarb et al., 2015).

Lead and violence: all the evidence

Kevin Drum offers a response to a recent meta-study on the link between lead and violence, blogged by me here.

I’ll take this moment to explain why the lead-violence connection never has sat that well with me.

Let’s say we are trying to explain why 2022 America is richer than the Stone Age. We could cite “incentives, policy, and culture,” noting that any accumulated stock of wealth also came from these (and possibly other) factors. You might disagree about which policies, or which cultural features of modernity, and so on, but the answer to the question pretty clearly lies in that direction.

Now let us say we are trying to explain why America today is richer than Albania today. You would do just fine to start with “incentives, policy, and culture.” You could add in some additional factors, such as superior natural resources, but you would be on the same track as with the Stone Age comparison. You would not have to summon up an entirely new theory.

Why is Nashville richer than Chattanooga? Again, start with “incentives, policy, and culture,” noting you might need again supplementary factors.

Broadly the same theory is applying to all of these different comparisons. Across time, across space, across countries, and across cities. There is something about this broad unity that is methodologically satisfying, and it helps confirm our view that we are on the right track in our inquiries.

Now consider the lead-crime connection. Insofar as you elevate the connection as very strong, you are tossing out the chance of achieving that kind of unity.

Why was violent crime so often more frequent in earlier periods of human history? It wasn’t lead, at least not for most periods, perhaps not for any of the much earlier periods.

Why was there more peace in Ethiopia five years ago than in the last few years? Again, whatever the reasons it wasn’t a change in lead exposure.

Why is the murder rate in Haiti today much higher than during the Duvaliers? Again, no one thinks the answer has much to do with changes in lead exposure. Mainly it is because political order has collapsed, and the country is ruled by gangs rather than by an autocratic tyranny.

How about the violence rate in the very peaceful parts of Africa compared to the very violent parts? Again, lead is rarely if ever going to be the answer to that one.

So we know in the true, overall model big changes in violence can happen without lead exposure being the driving force. Very big changes. In fact those big changes in violence rates, without lead being a major factor, happen all the time.

And many of those big changes are mysterious in their causes. It really isn’t so simple to explain why different parts of Africa have different murder rates, often by very significant amounts. You can hack away at the problem (e.g, Kenya and Tanzania have very different histories), but there is no simple “go to” theory. Furthermore, since both violence and peace often feed upon themselves, in a “broken windows” increasing returns sort of way, the initial causes behind big differences in violence outcomes might sometimes be fairly slight and hard to find.

That to my mind makes “the true model” somewhat biased against lead being a major factor in changes in violence rates. In the broader scheme of things, lead exposure seems to be a supplementary factor rather than a major factor. It doesn’t rule out lead as a major factor, either logically or statistically, if you wish to explain why U.S. violence fell from the 1960s to today. But the true model has a lot of non-lead, major shifts in violence, often unexplained or hard to explain.

Addendum: I am also surprised by Kevin’s comment that there isn’t likely to be much publication bias in lead-violence studies. I take publication bias to be a default assumption, namely the desire to show a positive result to get published. That hardly seems unlikely to me at all. And in this particular case there is even a particular political reason to wish to pin a lot of the blame on lead exposure. Correctly or not, people on the Left are much more likely to elevate lead exposure as a cause of social problems.

And to repeat myself, just to be perfectly clear, it strikes me as unlikely that the effect of lead exposure on violence in zero is the last seventy years of the United States.

Sunday assorted links

1. Adam Tooze worrying about the UK. I wonder: what would comparable income data on “British-Americans” look like?

2. The Hydraulis of Dion. And more, including a demo.

4. How men rate women, and how women rate men.

5. New O’Shaughnessy fellowships, appears to be a very promising opportunity.

A new paper on the Industrial Revolution

I have not yet read it, but surely it seems of importance:

Although there are many competing explanations for the Industrial Revolution, there has been no effort to evaluate them econometrically. This paper analyzes how the very different patterns of growth across the counties of England between the 1760s and 1830s can be explained by a wide range of potential variables. We find that industrialization occurred in areas that began with low wages but high mechanical skills, whereas other variables, such as literacy, banks, and proximity to coal, have little explanatory power. Against the view that living standards were stagnant during the Industrial Revolution, we find that real wages rose sharply in the industrializing north and declined in the previously prosperous south.

That is by Morgan Kelly, Joel Mokyr, and Cormac Ó Gráda, forthcoming in the JPE. Here are earlier versions of the paper.

What I’ve been reading

1. Greg Berman and Aubrey Fox, Gradual: The Case for Incremental Change in a Radical Era. A good book for sane centrists, and they claim to have been partly inspired by our subheading “Small Steps Toward a Much Better World.” Did you know that putting in the “much” was Alex’s idea? At first I resisted but clearly he was correct.

2. Jerry Saltz, Art is Life: Icons and Iconoclasts, Visionaries and Vigilantes, and Flashes of Hope in the Night. Art reviews from the New York magazine guy. Fun to read, mostly sane, and helps the reader understand the ascent of Wokeism in the art world. It is not that so many art buyers or curators are racist. Rather, art is super-hierarchical in the first place (try telling the market that a great textile should go for as much as a famous painting), and that, in unintended cross-cutting fashion, that tends to produce apparent biases across both gender and race. Black and women artists really have been undervalued, and many still are, though this is changing (yes Kara Walker sketches are overpriced right now). A lot of people are just blind on this one, sorry people but I mean you. As a side note, Saltz enjoys Rauschenberg more than I do, though I would not dispute the historical importance of his work.

3. Geoff Emerick, Here, There, and Everywhere: My Life Spent Recording the Music of the Beatles. If you want a book sympathizing with Paul McCartney as the guy who made the Beatles tick, and portraying George Harrison as a suspicious, less than grateful whiner, this is for you. And so it is. By the way, contrary to some very recent accounts, Emerick affirms that “Yellow Submarine” is basically a McCartney composition. He even notes that Lennon cut some demos of it, which has led some recent commentators to conclude it was Lennon’s composition. The demos are quite raw, so maybe the song is joint?

4. Deborah E. Harkness, The Jewel House: Elizabethan London and the Scientific Revolution. A big and neglected piece of the puzzle for the breakthrough of the West, focusing on Elizabethan times, skill in symbolic manipulation, and the origins of the scientific revolution. Recommended.

Philip Kitcher, On John Stuart Mill, is a nice short introduction.

And John T. Cunningham, This is New Jersey, from High Point to Cape May, dates from 1953 and thus is intrinsically interesting. Hudson County really is remarkably densely populated, and back then it was a big deal that baseball was invented in Hoboken.

I appear on the Jolly Swagman podcast

From the Jolly Swagman himself:

“Hey Tyler – we’ve just published our podcast on Talent – thanks again for a fun chat.

Link here in case you want to share it on Marginal Revolution:

https://josephnoelwalker.com/142-talent-is-that-which-is-scarce-tyler-cowen/

Topics / questions we discussed include:

- whether you would have backed a 20-something year old John Keats

- why putting ellipses in emails signals high status

- your most irrational belief

- what biographers can teach us about talent identification

- what made the Henry George seminar you ran with Peter Thiel so good

- how Sarah Ruden furnishes herself with massive context to gain an edge over other translators

- What should Obi-Wan have told Anakin Skywalker before he became Darth Vader

- the Sumerian bar joke

- whether countries can be both highly capable of solving collective action problems and extremely innovative

- your view of Australian talent and what makes it unique

Thanks and happy new year!”

Happy New Year everyone!