Category: Education

Outsourcing for everything

Why not grade exam papers in India? Brad DeLong offers the link. The obvious question is what we really need professors for anyway — are we simply magnets of personality to keep students interested?

Speaking of Brad, he and Jacqueline Passey have unknowingly combined forces to make me mighty curious about Firefly. The Amazon ratings are in the stratosphere. My TV education continues. But if I ever felt obliged to watch the medium, my already overbooked life would simply fall apart…

Politically Incorrect Paper of the Month v.4

This month’s Journal of Law and Economics has several superb papers. Today, I discuss a shocker from Nobelist James Heckman and colleagues, Labor Market Discrimination and Racial Differences in Premarket Factors (subs. required, free version).

A 1996 paper by Neal and Johnson (jstor) showed that most of the black-white wage differential could be explained by AFQT scores. IQ scores, however, can be influenced by schooling and on average blacks receive worse schooling than whites so Heckman et al. control for schooling and look for even earlier measures of ability (Neal and Johnson use teenage scores). The results are not encouraging. After throwing all kinds of factors into the analysis they are able to increase the unexplained wage gap somewhat but no matter how far back they go they still find big ability differences, even in children as young as 1-2 years of age.

The real shock, however, does not come until near the end of the paper where Heckman et al. compare blacks and Hispanics. I will let the authors speak:

Minority deficits in cognitive and noncognitive skills emerge early and then widen. Unequal schooling, neighborhoods, and peers may account for this differential growth in skills, but the main story in the data is not about growth rates but rather about the size of early deficits. Hispanic children start with cognitive and noncognitive deficits similar to those of black children. They also grow up in similarly disadvantaged environments and are likely to attend schools of similar quality. Hispanics complete much less schooling than blacks. Nevertheless, the ability growth by years of schooling is much higher for Hispanics than for blacks. By the time they reach adulthood, Hispanics have significantly higher test scores than do blacks. Conditional on test scores, there is no evidence of an important Hispanic-white wage gap. Our analysis of the Hispanic data illuminates the traditional study of black-white differences and casts doubt on many conventional explanations of these differences since they do not apply to Hispanics, who also suffer from many of the same disadvantages. The failure of the Hispanic-white gap to widen with schooling or age casts doubt on the claim that poor schools and bad neighborhoods are the reasons for the slow growth rate of black test scores.

TV and the Flynn Effect

Ever notice that old tv shows and movies are boring? Why should this be? Were people more easily entertained thirty years ago? Were they dumber? Why yes, they were.

IQ test scores have been increasing over time, a fact known as the Flynn effect. No one knows exactly why but some ascribe the effect to the greater cognitive demands of modern life. Writing in the NYTimes Magazine Steven Johnson provides some interesting evidence from television. He argues, I think correctly, that the plot structure of television dramas from a generation ago are much simpler than modern equivalents.

The following graph illustrates a typical Starsky and Hutch episode:

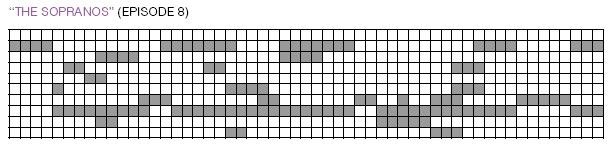

The x axis indicates time and the y axis different plot-threads – the opening and closing points are the little "aha" that brings the story full circle with a little comedic twist.

Compare with the Sopranos in which plot-threads and characters interweave across many different episodes:

Is it any wonder that modern viewers are bored by older television?

Johnson wants to argue that the changes in television are part of what is causing the Flynn effect (he doesn’t say this explicitly in the NYTimes article for that you have to read his piece in the April Wired (not yet online) – very meta.) Of course, it’s difficult to say what is cause and what is effect – probably both are involved. (See Dickens and Flynn for more on that theme.)

I liked Johnson’s argument for a new system of tv ratings. Don’t focus on the content focus on the complexity of the content’s presentation.

Instead of a show’s violent or tawdry content, instead of

wardrobe malfunctions or the F-word, the true test should be whether a

given show engages or sedates the mind. Is it a single thread strung

together with predictable punch lines every 30 seconds? Or does it map

a complex social network? Is your on-screen character running around

shooting everything in sight, or is she trying to solve problems and

manage resources? If your kids want to watch reality TV, encourage them

to watch ”Survivor” over ”Fear Factor.” If they want to watch a

mystery show, encourage ”24” over ”Law and Order.” If they want to

play a violent game, encourage Grand Theft Auto over Quake.

Addendum: Ted Frank points out that cable television has added to the phenomena, by fragmenting viewers it has allowed higher quality (less common denominator) content to filter through.

Views I hold without much evidence

1. China will someday just get up and attack Taiwan. Recent progress aside, how many rational decisions have Chinese governments made in the last six hundred years? And its inability to get over the idea of conquering Taiwan will stop China from democratizing anytime soon. I am not in general a "China hawk," but I view Taiwan as, sadly, a goner. I remain amazed by how many "liberal" Chinese simply think Taiwan is "theirs."

2. High-quality American high school students study too much and have too many extracurricular activities. Yes, I am thinking zero-sum game. It would be better for most of them to go out and get jobs bagging groceries. They would learn more about the real world.

3. Shaquille O’Neal is the greatest NBA player ever, bar none. (Well, OK, there is some evidence for this.)

4. The first two Star Wars installments (yes, that includes the one with Jar Jar Binks) were excellent, and will someday be recognized as such. Maybe you view those films as engaged in excessive pandering. I see them as a Bildungsroman (Anakin/Darth) which makes few concessions to popular taste and also presents public choice theory in sophisticated fashion. Lucas simply doesn’t care if the films make no sense in stand-alone fashion, nor should he. By the way, in the interests of personal safety, I’ve decided to limit my number of car trips before May 19.

5. High-quality barbecue (alas, not available here in Virginia) is better than most expensive French restaurants. And I love most expensive French restaurants, especially when someone else is paying.

6. Aesthetic judgments are, in principle, objective rather than arbitrary.

Bryan Caplan on me

Aside: Tyler Cowen said it [my, Bryan’s, paper] was unpublishable. I told him he was wrong after Social Science Quarterly took it, but he replied that I was being "too essentialist"!

Here is Bryan’s full post. Here is some background.

Does prekindergarten help kids?

…early education does increase reading and mathematics skills at school entry, but it also boosts children’s classroom behavioral problems and reduces their self-control. Further, for most children the positive effects of pre-kindergarten on skills largely dissipate by the spring of first grade, although the negative behavioral effects continue. In the study, the authors take account of many factors affecting a child, including family background and neighborhood characteristics. These factors include race/ethnicity, age, health status at birth, height, weight, and gender, family income related to need, language spoken in the home, and so on.

In other words, you learn both how to read and how to raise hell, but a head start is useful only for the latter talent. Here is the link to the summary and study.

Markets in Everything: Nein!

Markets in Everything usually deals with unusual items but today’s post is about a German website where buyers and sellers bid on labor contracts. Here’s the idea:

The

concept of jobdumping.de is simple. An employer posts a job that needs

doing, along with the maximum wage he or she is willing to pay.

Interested job seekers then compete with each other for the job by

underbidding, meaning the employer ends up with the person willing to

do the job for the least amount of money.

The system can also

work the other way, with workers entering their skills in the auction

at the minimum price they’re willing to work for, and interested

employers then push the wage up as they outbid each other.

Nothing unusual about that – freelancers as well as firms bid on contracts like this all the time. And yet in Germany, where unemployment is at a record high, this website has generated a furious response:

…some German labor market experts have had harsh words for the Internet site. Dirk Niebel of the Liberal Democratic party even went so far as to call the premise "immoral" in an interview printed in the Berliner Zeitung on Tuesday.

"I find it strange," he said. "It smacks of a slave market."

Freedom is slavery. Amazing.

Thanks to Mike Jackmin for the pointer.

Are economic graduate students conservative?

Economists are often thought of as conservative, but that was not the case in the previous study [1985] nor in this one. In this study, 47 percent of the students classified themselves as liberal, 24 percent as moderate, 16 percent as conservative and 6 percent as radical. (Six percent stated that politics were unimportant to them.) These percentages are very similar to the last study, although the share of those identifying themselves as radicals declined (from 12 percent). The students perceived their views as slightly more liberal than those of their parents, 40 percent of whom they classified as liberal, 36 percent as moderate, 16 percent as conservative and 3 percent as radical.

By the way, Chicago graduate students are now less conservative than those at Stanford; Chicago is rapidly losing its uniqueness.

Do note that "liberal" economists are often fairly conservative, at least relative to the left as a broader political class. Economics gives plenty of reasons (whether you agree with them or not) to defend government intervention. At the same time the ideas of cost and constraint remain prominent.

I view most Ivy League economics graduate students as highly peer conscious. They want to fit into the views of the intelligentsia surrounding them, and above all they would find membership in the Republican party a source of great social embarrassment. They are fiscally conservative Democrats who are liberals on social issues, but don’t really much toy with the idea of becoming libertarian. They prefer to put themselves in the class of "good-thinking people," without always engaging in or welcoming the necessary debates.

The above quotation is taken from David Colander’s article in the Winter 2005 Journal of Economic Perspectives.

The definitive work on the policy views of social scientists is being done by Daniel Klein and Charlotta Stern, read more here. And I am pleased to announce that Dan will be joining us at George Mason next year as a new member of the faculty.

My idea of how to clean up the house

Take one of the many large piles of papers and books lying around the house, and start reading the material. By the time all the material is read, the pile is gone.

Markets in everything

[some University of Michigan students] are getting $100 cash payments for keeping their dorm rooms presentable and opening their doors so prospective students and their parents can take a look during campus visits…

Participants must let tour groups see their room in the middle of the day, and have to be out of bed and dressed [imagine that!], said Randi Johnson, the university’s housing outreach coordinator. Display of anything illegal, offensive or banned is forbidden.

Here is the story, and thanks to Michael Rizzo for the pointer.

Is HOPE a virtue?

In response to middle-class anxiety about college costs, states have dramatically increased funding for "merit-based" scholarships. Georgia’s HOPE program (Helping Outstanding Pupils Educationally), begun in 1993, is the model. HOPE covers tuition, fees and book expenses for any high-school graduate earning a B average.

David Mustard, who spoke here last week, and co-authors have written a series of papers asking in effect, Is HOPE a virtue? Predictably, high-school GPAs increased markedly after 1993 with a pronounced spike at B. SAT scores, however, did not increase so grade inflation, not academic improvement, appears to be the cause. Once in college students must maintain a B average to keep their scholarship – the program is rather lax on how many or what courses must be taken however. The result is that scholarship students take fewer classes, take easier classes and when the going gets tough they withdraw more often. Apparently HOPE comes at the expense of fortitude.

HOPE increases the number of students enrolled in GA colleges only modestly and the bulk of the increase comes from students who are induced by the cash to stay in GA, instead of going to school in another state, rather than from students who, without HOPE, would never have gone to college. What do the students do with the cash they save on tuition? Cornwell and Mustard (2002) find that car registrations increase significantly with county scholarships!

Bottom line: HOPE is neither charitable nor prudent. The bullk of the money is a simple transfer to students and their parents. To the extent that HOPE has incentive effects these appear to reduce not increase educational effort and achievement.

What do economic indicators mean?

This book, The Secrets of Economic Indicators, appears to be a handy reference work, here is a review. Thanks to www.politicaltheory.info for the pointer.

Why I worry about essays for the new SAT

An essay that does little more than restate the question gets a 1. An

essay that compares humans to squirrels — if a squirrel told other

squirrels about its food store, it would die, therefore secrecy is

necessary for survival — merits a 5 [a good score]. Brian A. Bremen, an English

professor at the University of Texas at Austin, notes that the writer

provides only one real example. Nevertheless, he says, the writer

displays "a clear chain of thought" and should be rewarded, "despite

his Republican tendencies."

Read more here.

My Law and Literature class today

Today I start my Law and Literature class, my reading list is here. If you are wondering what I am excerpting, from the Bible we are doing Exodus, Deutoronomy, and Job,

from Melville we are doing "Bartleby," and from Kafka we are doing "In

the Penal Colony." All are favorites of mine. Check out the list for

the rest plus five films.

By the way did you know the following?

Students asked to watch five seconds of soundless videotape of a

teacher in the classroom came up with evaluations of the teacher’s

effectiveness that matched those given by his own students after a full

semester of classes.

The link is here, already supplied by Alex immediately below.

Does academia discriminate against right-wingers?

Jonathan Klick — a smart economist, not unsympathetic to markets, writes me the following:

I’ve been thinking a bit about all the stuff regarding the small number of folks on the right in academics in the mainstream press and on blogs, and I think people have missed an important point regarding cross sectional variation — I think the fact that you also see relatively few people on the right in the arts supports the supply side view of the empirical regularity more than the discrimination view. That is, there’s not really any differential barrier to entry into music, visual arts, writing, etc. for right wingers and yet those fields look at lot like academics in terms of personnel make-up. To my mind, this supports the view that, by and large, relatively fewer of the right’s brightest want to go into academics than is the case with the left.

I agree, but with one caveat. Many academic entrants are initially undecided in their political outlook, but social pressures sway them to the left. That being said, so many academic leftists have held their views from an early age. Academic life and discourse have, if anything, moderated their stances toward the center.

Both academic life and left-wing attitudes are correlated with the same basic status markers. Whether or not Democrats and academics are in fact more tolerant of others, at the very least they pretend to be. They also are, or at least pretend to be, more thoughtful, nuanced, intellectual, and internationalist [TC: This doesn’t stop them from being wrong about many things.] Most importantly, they take pride in identifying with these values. This will put most academics into the Democratic camp. Those that cannot become Democrats — such as myself — will often be libertarian or "independent" rather than registered or self-identifying Republicans. The Republican "pride markers" are, for many academic tastes, too nationalistic, religious, and involve too much "tough talk."

So the market-oriented or "right-wing" anthropologists will, ex post, experience negative bias in academia. Minority points of view are not always treated fairly. But that bias is not the initial reason why they are so outnumbered in the first place.