Category: Science

Beautiful People are Mean

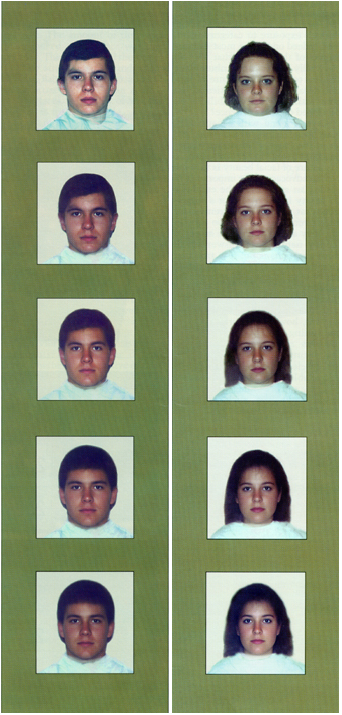

Several year ago, I read about the experiment showing that average faces are judged more beautiful than non-average faces. In Judith Rich Harris’s No Two Alike there is an arresting figure which demonstrates. With a little search on the web I was able to duplicate the figure, which is based on the original research. The top two pictures are the averages of two faces, the next two are averages of 4, 8, and 16 faces and the final picture is an average of 32 faces.

Wow, now I will no longer be upset when people say I have average looks.

Where does talent come from?

Here is Dubner and Levitt, from the Sunday New York Times:

[Anders] Ericsson and his colleagues have thus taken to studying expert

performers in a wide range of pursuits, including soccer, golf,

surgery, piano playing, Scrabble, writing, chess, software design,

stock picking and darts. They gather all the data they can, not just

performance statistics and biographical details but also the results of

their own laboratory experiments with high achievers.Their

work, compiled in the "Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert

Performance," a 900-page academic book that will be published next

month, makes a rather startling assertion: the trait we commonly call

talent is highly overrated. Or, put another way, expert performers –

whether in memory or surgery, ballet or computer programming – are

nearly always made, not born. And yes, practice does make perfect.

These may be the sort of clichés that parents are fond of whispering to

their children. But these particular clichés just happen to be true.

Here is the link. Here is The Economist on Ericsson. Here is Ericsson’s home page. Here is more from Dubner and Levitt, including further links to papers.

Addendum: Here is an archive link to the Sunday article.

von Neumann’s poker-playing machine

Here is Tim Harford’s article on poker and game theory, from today’s Financial Times. Excerpt:

…he admits that it is only a matter of time before anyone will be able

to download a free poker robot that will outplay the world champion. At

that point, people may not care to risk money online against

unidentified opponents.

But does Natasha like my books?

Despite the strong positive feelings that characterize newlyweds, many marriages end in disappointment. To understand this shift, the authors argue that although newlyweds’ global relationship evaluations may be uniformly positive, not all spouses base their global adoration on an accurate perception of their partner’s specific qualities. Two longitudinal studies confirmed that whereas most newlyweds enhanced their partners at the level of their global perceptions, spouses varied significantly in their perceptions of their partners’ specific qualities. For wives, but not for husbands, more accurate specific perceptions were associated with their supportive behaviors, feelings of control in the marriage, and whether or not the marriage ended in divorce. Thus, love grounded in specific accuracy appears to be stronger than love absent accuracy.

Here is the paper, and thanks to Robin Hanson for the pointer.

Testable predictions about dancing

There will be no society anywhere on Earth where all dancing is done

in secret. Dancing will be a public phenomenon everywhere. Whereas a

man or woman might practice alone, the end product will always involve

witnesses.There will be no society on Earth where all the dancing done by men is away from the eyes of women.

Women, far more than men, will find the skill with which a potential

mate can dance far more of a factor which influences their choices of

mate. This will be true of all societies.Women will get the most pleasure from dancing (except perhaps when

taking the contraceptive pill) when they are at the fertile peak of

their menstrual cycle.

There is much more, and thanks to Newmark’s Door for the pointer.

Addendum: Here is a working link.

Who needs self-awareness?

Self-awareness, regarded as a key element of being human, is

switched off when the brain needs to concentrate hard on a tricky task,

found the neurobiologists from the Weizmann Institute of Science in

Rehovot, Israel.The

team conducted a series of experiments to pinpoint the brain activity

associated with introspection and that linked to sensory function. They

found that the brain assumes a robotic functionality when it has to

concentrate all its efforts on a difficult, timed task – only becoming

"human" again when it has the luxury of time.

Here is the full story.

The Gender Imbalance Disequilibrium

China’s gender imbalance is now 117 boys for every 100 girls and for second and third children (when allowed) the imbalance can be as high as 151 boys for every 100 girls. Millions of men, perhaps 15% of the population, may not be able to find wives.

"The world has never before seen the likes of the

bride shortage that will be unfolding in China in the decades ahead," says AEI demographer Nicholas Eberstadt.

The Chinese government has responded by making selective abortion illegal and by giving significant bonuses to parents of girls. Yet blackmarket ultrasound is available and, according to 60 Minutes, in demand. Some reports suggest that the gender imbalance is increasing.

Yet from the perspective of evolutionary fitness having a girl in China is now much better than having a boy. Boys who can’t find mates won’t be giving their parents any grandchildren. Will it take a generation of parents without grandchildren for evolutionary incentives to kick in? Why hasn’t this happened already? How hard is it to figure out that having a boy, especially if you are poor, means the end of your lineage?

Hat tip to Paul Rubin for pointing out this puzzle to me.

The benefits, and costs, of anxiety

I don’t worry much, so it is good I survived my 20s:

Using the survey to follow the fortunes of 5,362 people born in 1946,

the researchers found that those individuals who had higher anxiety –

as determined by the opinion of their school teacher when they were 13

– were significantly less likely to die in accidental circumstances

before they were 25 (only 0.1 per cent of them did) than were

non-anxious people (0.72 per cent of them did). Similar trends were

observed when anxiety was measured using the teachers’ anxiety

judgments when the sample were 15-years-old, or using the sample’s own

completion of a neuroticism questionnaire when they were 16. By

contrast, anxiety had no association with the number of non-accidental

(e.g. illness-related) deaths before 25. “Our findings show, for the

first time in a representative sample of humans, a relatively strong

protective effect of trait anxiety”, the researchers said.It’s

not all good news for anxious people though. After the age of 25 they

started to show higher mortality rates than calmer types thanks to

increased illness-related deaths.

Here is the link and also the paper. Elsewhere on BPS Digest, the language you speak influences your personality.

Charlie and the Missing Link

From Boing Boing Blog. Related story here.

The gap gets smaller

Prayer doesn’t reduce mortality and neither does alcohol. In both cases, more evidence that there is no god.

Are You Boring Me?

Frankly, I could give a few of these out as Christmas presents.

MIT Media Lab researchers are building a device to help autistic people

determine if they’re boring or annoying the person they’re talking to. The

"emotional social intelligence prosthetic device" is a camera that clips on

eyeglasses and feeds images to a small computer that uses image recognition

software to characterize emotions. If the listener doesn’t seem to be engaged,

the device vibrates to alert the wearer.

From David Pescowitz at Boing Boing Blog.

The future of science

If all this happens, or even half of it, I won’t count as an economist any more. Thanks to kottke.org for the pointer.

AI, Consciousness and Robot Outsourcing

One of my "absurd views" is that the first computer to become conscious was Deep Blue playing against Gary Kasparov in 1997. It only happened for a moment but in one spectacular move Deep Blue performed like no computer ever had before. After the game, Kasparov said he felt a presence behind the machine. He looked frightened.

Ken Rogoff, a top-flight economist and chess prodigy, wonders whether we don’t all have a little something to fear.

But the level that computers have reached already is scary enough.

What’s next? I certainly don’t feel safe as an economics professor! I have no doubt that sometime later this century, one will be able to

buy pocket professors – perhaps with holographic images – as easily as

one can buy a pocket Kasparov chess computer today.

Rogoff thinks that the upheavals caused by cheap AI will be far more important than those caused by low-wage labor from India and China.

…will

artificial intelligence replace the mantra of outsourcing and

manufacturing migration? Chess players already know the answer.

Philosophical implications of inflationary cosmology

Recent developments in cosmology indicate that every history having a nonzero probability is realized in infinitely many distinct regions of spacetime. Thus, it appears that the universe contains infinitely many civilizations exactly like our own, as well as infinitely many civilizations that differ from our own in any way permitted by physical laws. We explore the implications of this conclusion for ethical theory and for the doomsday argument. In the infinite universe, we find that the doomsday argument applies only to effects which change the average lifetime of all civilizations, and not those which affect our civilization alone.

Got that? Here is the paper. Here is brief background.

It seems if you count all possible universes (or call them parts of our multiverse, whatever) as normatively relevant, none of your actions matter in consequentialist terms.

As to how our world, and our decisions, matter at the margin, we delve into the murky waters of infinite expected values. With an infinity of alternatives out there, our little add-on doesn’t seem to make any difference for the grand total. Why should even you raise the average outcome across universes? (TC yesterday: "No, Bryan, we are not leaping up Cantorian levels of infinity, it is just one version of you getting another Klondike bar.")

One option is that only our universe, or some other "in-group," matters. The other universes cannot count for less, rather they must count for nothing. I recoil at such a thought, but it does avoid the mess of infinities. Alternatively, we might embrace some version of Buddhism.

On the bright side, philosophic talk about modality is no longer so problematic but rather refers to facts about other existing universes. Since that problem threatened to bring morality to its knees anyway ("what do you mean, you "could" have done something different? You did what you had to do."), maybe I don’t feel so bad after all. And who should care if I do feel bad? The other me feels fine. Infinity has its benefits, and there are many worse problems.

You should lower your probability that God exists, since the Anthropic Argument will dispense with the Argument from Design. Only the ordered pockets of the multiverse can wonder about why we are here and why things seem to run so smoothly.

That’s a lot to swallow in one day, but it seems the probability of all those propositions just went up.

Addendum: Have I mentioned that inflationary cosmology and its implications fit my crude, pathetic intuitions? Since we have a universe, I feel it must somehow be a kind of cosmic "free lunch." And once you open the door for free lunches, why stop at just one? There is no good reason to rely on our locally-evolved common sense intuitions when doing philosophic cosmology.

Fluctuating inflation field

This is cosmology, not monetary policy. Guth’s theory of inflation has just received a big boost from the data. Here is Andrei Linde’s portrayal of how an inflationary field fluctuates. Here is a slower version with higher resolution. Here is Linde’s home page, which has many other time wasters.

Addendum: Best sentence I read today: "Galaxies are nothing but quantum mechanics writ large across the sky," by Brian Greene.