What Worked in 1918-1919?

The influenza pandemic of 1918 was the most contagious calamity in human history. Approximately 40 million individuals died worldwide, including 550 000 individuals in the United States...[C]an lessons from the 1918-1919 pandemic be applied to contemporary pandemic planning efforts to maximize public health benefit while minimizing the disruptive social consequences of the pandemic as well as those accompanying public health response measures?

That’s the question Markel et al. analyzed in 2007 by gathering historical data on outcomes and what 43 US cities, covering about 20% of the US population, did to combat influenza in 1918-1919.

Nonpharmaceutical interventions were considered either activated (“on”) or deactivated (“off”), according to data culled from the historical record and daily newspaper accounts. Specifically, these nonpharmaceutical interventions were legally enforced and affected large segments of the city’s population. [1] Isolation of ill persons and quarantine of those suspected of having contact with ill persons refers only to mandatory orders as opposed to voluntary quarantines being discussed in our present era. [2] School closure was considered activated when the city officials closed public schools (grade school through high school); in most, but not all cases, private and parochial schools followed suit. [3] Public gathering bans typically meant the closure of saloons, public entertainment venues, sporting events, and indoor gatherings were banned or moved outdoors; outdoor gatherings were not always canceled during this period (eg, Liberty bond parades); there were no recorded bans on shopping in grocery and drug stores.

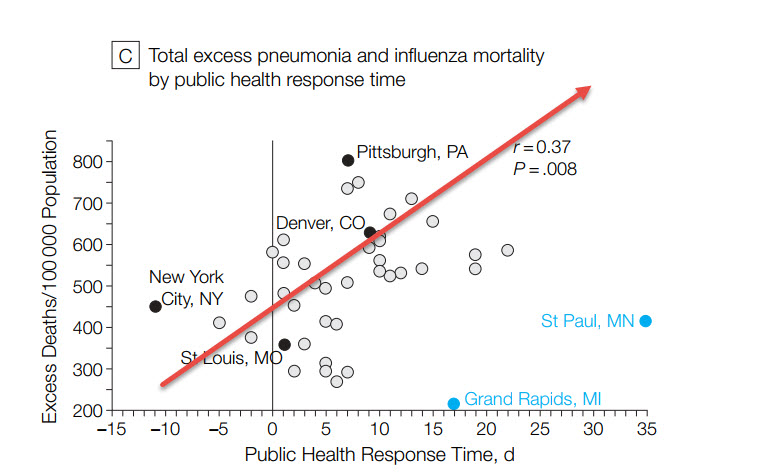

The authors define “public health response time” as the number of days from the day the excess death rate was double baseline to the day that at least one of their three key public health measures was implemented. Cities that responded very early have a negative public health response time. The basic result is shown in the figure below. The longer the public health response time the greater the total excess deaths (the arrow is my least squares eyeball).

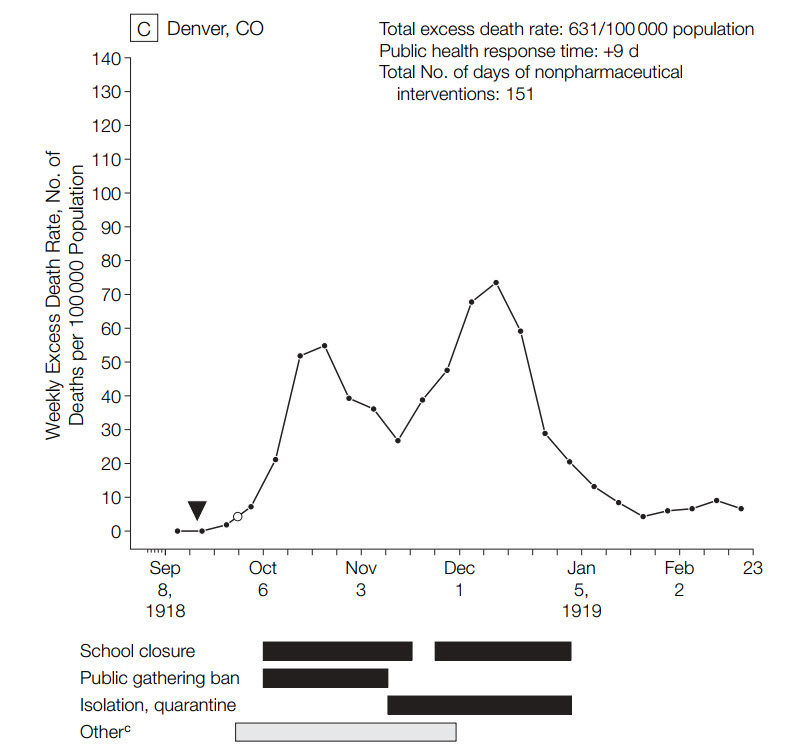

Moreover, although it’s difficult to control for other factors, cities that combined school closures, isolation and quarantining, and public gathering bans tended to do better. Some cities let up on their public health interventions and these cities seem to correlate well with bi-modal distributions in excess death rates, i.e. the death rate increased. Denver was an example where the public gathering ban was dropped and the school ban was lifted temporarily and the excess death rate rose after having fallen.

The authors conclude:

…the US urban experience with nonpharmaceutical interventions during the 1918-1919 pandemic constitutes one of the largest data sets of its kind ever assembled in the modern, post germ theory era.

…Although these urban communities had neither effective vaccines nor antivirals, cities that were able to organize and execute a suite of classic public health interventions before the pandemic swept fully through the city appeared to have an associated mitigated epidemic experience. Our study suggests that nonpharmaceutical interventions can play a critical role in mitigating the consequences of future severe influenza pandemics (category 4 and 5) and should be considered for inclusion in contemporary planning efforts as companion measures to developing effective vaccines and medications for prophylaxis and treatment. The history of US epidemics also cautions that the public’s acceptance of these health measures is enhanced when guided by ethical and humane principles.

Addendum: Another way of putting this is that China has largely followed the US model. Can the US do the same?