Category: Books

The greatest poet of the twentieth century?

I don’t think it is crazy to pick the late Pablo Neruda, whose one hundredth birthday is today. (Yeats or Wallace Stevens are serious competition, however. Not to mention Rilke, who is probably my first choice…) Read this appreciation. Here are three poems in English, but no most poetry doesn’t translate well. Here is a (much better) concordance of poems in Spanish.

But why did so many artists love Stalin?

Neruda had become an ardent communist. Over the years he wrote a lot of sincerely felt, but otherwise weak, didactic poems denouncing Western imperialism. His strident praise for the Communist Party seems at best naive, and his admiration for Stalin, whom he never disavowed, can be hard to stomach. Such figures as Octavio Paz and Czeslaw Milosz broke with him over communism. In his Memoirs, completed just a few days before his death, he called himself “an anarchoid,” and that seems closer to the truth. “I do whatever I like,” he said.

Nonetheless, Neruda’s social and political commitments were crucial to his life and work. He was elected senator for the Communist Party in Chile in 1945. He campaigned for Gabriel González Videla, who became president the next year — and whose government then outlawed the Communist Party. Neruda denounced him, and in 1948 he was accused of disloyalty and declared a dangerous agitator. After a warrant for his arrest was issued, he went into hiding in Chile, then fled to Argentina and traveled to Italy, France, the Soviet Union and Asia. (His brief stay on the island of Capri during his exile was fictionalized in the touching film “Il Postino.”)

If I could have the answers to five questions in political science/sociology, the appeal of Stalinism to intellectuals would be one of them.

Addendum: Tom Myers notes that it is also the hundredth birthday of Deng Xao-Ping, here is a full list of famous July 12 babies.

What are the most popular library books?

65 percent of Americans use the nation’s 16,000 libraries, and those libraries spend almost $2 billion on books each year, about a fifth of the total market.

So which library books are most popular? And does it mirror the bestseller lists?

Here is the list of the top fifteen, an Adobe reader is required. Number one is The South Beach Diet, followed by some of the usual political books and Eats, Shoots and Leaves. The first book I enjoyed comes at number six with Brian Greene’s The Fabric of the Cosmos, here is my earlier summary.

My question is whether people are more likely to buy books and never read them, or take books out of the library and then never read them. The naive economist might think that you get more phoney-baloney behavior when the books are free. I suspect the opposite is true. If the book costs nothing, bringing it home involves little signaling or self-signaling. It might impress your neighbor to see a weighty tome on your bookshelves, but only if you had to spend money. So the good news would be that those people actually wanted to read the Greene book.

Here is the full story.

How to read difficult books

Yes, today is the hundredth anniversary of “Bloomsday,” June 16, 1904, the day on which the adventures of Leopold Bloom (Ulysses) start. The book, long a favorite of mine, is not nearly as difficult as it is sometimes thought to be.

Here are a few tips for reading otherwise difficult works of fiction:

1. Try reading the last chapter first. Don’t obsess over the sequential.

2. Read through the first time, following each voice or character, skipping passages as you need to. Then reread the book as a whole in order. This works especially well for Faulkner.

3. Try reading the first fifty pages three times in a row before proceeding.

4. Don’t be afraid to skip over material and return to it later. This is necessary for the first fifty pages of Nostromo.

5. Read through without stopping, and then try the book again, but with some idea of where things are headed.

6. Read some of the secondary literature first. I don’t like CliffNotes, but in general don’t be afraid to go low when looking for help.

7. Read the book out loud to yourself or to others.

8. Simply give up.

I’ve found that some combination of these tricks almost always works.

By the way, here are some recent writings on Ulysses and the centenary.

Crowds are wiser than you think

I’m reading James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds – so far, it’s very good! Steve Sailer posted the following comment on the book:

…he doesn’t really explain why pseudo-markets like the Iowa Election Market tend to be more accurate than traditional predictive tools like the Gallup Poll, although the answer is obvious: because they piggyback off traditional sources of information like Gallup. For example, participants in the IEM look at not just the Gallup Poll but a dozen others. Without these pollsters spending large amounts of money to generate information, however, the market players would be pretty clueless. Similarly, if the crowd takes the average of the 11pm weather forecasts of the weatherguys on Channels 2, 4, and 7, they may well beat the best individual forecast, but that doesn’t mean the crowd could beat the professional weathermen — unless the pros first tell them what they think the weather is going to be.

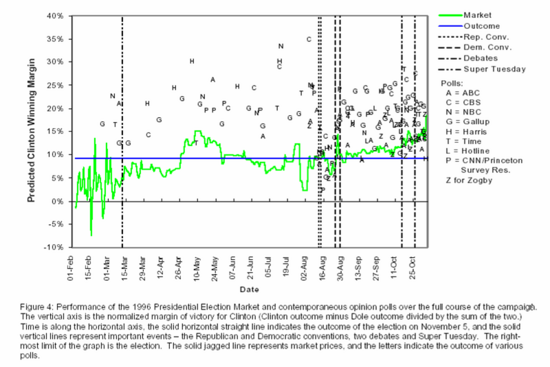

Clearly, there is some truth to this – Hayek said markets are “marvelous” he didn’t say “miraculous.” But a lot more goes on in information markets than averaging. The green line in the figure below (click to expand) shows the Iowa market prediction for the 1996 Presidential election. The blue line is what actually occured. The spots are various polls. Now notice that from February through August every single poll overpredicted Clinton’s victory and every single poll, with but one exception, was above the market prediction. This means that the market prediction could not possibly be an average of the polls.

Surowiecki gives a number of other examples where the wisdom of the crowds cannot be explained by averaging of expert opinion even though averaging is an important reason why crowds can be wise.

Econometrics and New Yorker fiction

What kind of stories get published?

Ms. [Katherine] Milkman, who has a minor in American studies, read 442 stories printed in The New Yorker from Oct. 5, 1992, to Sept. 17, 2001, and built a substantial database. She then constructed a series of rococo mathematical tests to discern, among other things, whether certain fiction editors at the magazine had a specific impact on the type of fiction that was published, the sex of authors and the race of characters. The study was long on statistics…the thesis segues to the “Kolmogorov-Smirnov Two-Sample Goodness of Fit Test” and the “Pearson Correlation Coefficient Test.”

And what is the main conclusion?

…male editors generally publish male authors who write about male characters who are supported by female characters

More generally:

Under both [fiction] editors the fiction in the magazine took as its major preoccupations sex, relationships, death, family and travel.

Are you surprised? And what does the magazine say?

“I was personally riveted by the whole thing,” said Roger Angell, a writer at The New Yorker who worked as a fiction editor during part of the period scrutinized by Ms. Milkman. He spent a significant amount of time talking to Ms. Milkman and helped connect her with other people at the magazine. He was charmed by the results but worries they may sow confusion.

“Some unpublished writers are going to read this and say, `I now know what I have to do to get published in The New Yorker,’ and it’s not helpful in that way,” he said. “In the end we published what we liked.”

Here is the New York Times story.

The bottom line: Expect to see more of this kind of analysis in the future. In the longer run I expect all of the humanities disciplines to have a quantitative branch.

The power of cinema

The Iliad is now number 106 on the Amazon list. Of course this number probably will be revised by the time you read this…

How well do art books sell?

The answer is simple, art books do not sell many copies. Not counting photography books and “how to” books, the bestselling art book of 2003 was Ross King’s Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling, which sold 55,693 copies. In the U.S. only four other art books sold over ten thousand copies, again excluding photography and how to books. The amazing fact, from my point of view, is just how many art books you will find in your average Borders or Barnes & Noble. Of course many end up returned to the publisher. The copies get you in the door to buy The da Vinci Code there rather than in Wal-Mart.

Despite having a much smaller population, the British show a greater interest in art books. The bestselling art book in the U.K., a Titian catalog, topped the 60,000 mark.

From the April 2004 issue of The Art Newspaper, “Big Market but Few Books Bought,” not yet on-line.

China fact of the day

I remain disappointed by how our media underreport the news from China. Here is one possibly major development:

China will kick off reform of its publishing system by transforming the country’s publishing houses from public service institutions into business-oriented enterprises, an official from the Regulations Bureau of China’s Press and Publication Administration (CPPA), who wished to remain anonymous, told Interfax in an interview.

All publishing houses in China, except for the People’s Publishing House, will undergo this reform. The People’s Publishing House, meanwhile, will remain a public service institution. China currently has approximately 527 publishing houses, of which 20 to 30 are private enterprises. Most of these private publishers are engaged in publishing books.

“An experimental batch of publishing houses has been selected and their reshuffling and reform will be finished by the end of 2004,” the CPPA official explained. “Related information will not be publicized before the publishing system reforms are completed.”

Here is yet some further good news:

According to China’s WTO obligations, the retail book market will be open to foreign investment without any restriction after December 1, 2004. Foreign investors will have the final say in investment proportion, business fields and sales locations. Private investment will also be encouraged.

Here is the full (albeit brief) story. No, I don’t expect Chinese censorship to go away, but many restrictions are easing:

In 2003, the Party ordered reform for the whole cultural system. Some magazines and newspapers were no longer offered government and Party support to aid in distribution and revenue earning. As a result, over 600 newspapers and magazines folded, with some 400 more still facing challenges.

Here is more on opening up the Chinese publishing market. Milton Friedman, of course, was right to point out the strong connection between economic and political freedom. Here is a previous installment of “China Fact of the Day.”

Future Imperfect

Economist David D. Friedman has posted a draft of his manuscript, Future Imperfect, and he welcomes your comments.

This book is about technological change, its consequences and how to deal with them.

. . .

Much of the book grew out of a seminar I teach at the law school of Santa Clara University. Each Thursday we discuss a technology that I am willing to argue, at least for a week, will revolutionize the world. On Sunday students email me legal issues that revolution will raise, to be put on the class web page for other students to read. Tuesday we discuss the issues and how to deal with them. Next Thursday a new technology and a new revolution. Nanotech has just turned the world into gray goo; it must be March.

Since the book was conceived in a law school, many of my examples deal with the problem of adapting legal institutions to new technology. But that is accident, not essence. The technologies that require changes in our legal rules will affect not only law but marriage, parenting, political institutions, businesses, life, death and much else.

Markets in everything, the continuing saga

Leading British authors have auctioned off the names of characters in their new books to raise funds for charity.

Successful bidders at the third charity auction for victims of torture included a man who paid £1,000 to see his mother’s name appear in the next novel by the Irish writer Maeve Binchy. Another secured a role in books by two authors, bidding £950 for the children’s writer Philip Pullman and £240 for Sue Townsend, the creator of Adrian Mole.

And one author was also a bidder. Martina Cole, whose own work raised £220, paid £1,000 for her name to appear in the next book by Sarah Waters, who wrote Tipping the Velvet. Tracy Chevalier, whose novel Girl With A Pearl Earring, was adapted into a film, raised £300.

Adi McGowan, a City trader, paid for his mother, Muriel, to appear in the next Binchy book as a surprise birthday present. He said his mother was a fan of the author, whose novel Circle of Friends was adapted into a Hollywood film.

“I usually give a book as a birthday present,” he said. “Maeve’s a favourite. My mother has been waiting eagerly for her next book – now she’s actually going to be in it.”

Here is the full story. Here is a blog post about buying personalized romance novels more generally. Here is a related story of a couple who tried to auction off the naming rights for their baby. No company was willing to pay $500,000, so they named him Zane.

My take: To get mentioned on this blog, all you have to do is send us a useful link, failing that try $100 or more.

How to market culture, Italian style

When all else fails, offer a discount:

The cover of the current issue of Poesia, an Italian poetry magazine, shows a caricature of Eugenio Montale, a Nobel laureate in literature, standing on a cloud next to a tall stack of books. The headline reads, “One million volumes.”

It is a reference to the special edition of Montale’s poetry distributed during February with some copies of the Milan newspaper Corriere della Sera, which has a daily circulation of 686,000. Though the book reached that number in part because it was a giveaway, experts were nonetheless impressed, as well as by the book offered as an option along with the newspaper the following Monday: poems by Pablo Neruda. That book cost readers 5.90 euros, or about $7.20, and it sold more than 250,000 copies. There’s more poetry where that came from. Corriere della Sera plans a series of 30 books featuring the works of great poets, one each Monday, and at a relatively low price…

The strategy has been so successful that today nearly every Italian paper on the newsstand sells at least one discounted product – a book, DVD, CD or videotape – at least one day a week. The sales have helped raise circulation modestly and have given an unexpected infusion of cash to newspapers.

In other words, give newspapers a high prestige gloss, to mobilize eyeballs for advertisers. Note that cheap advertising than subsidizes quality poetry. Here is some more on the economics:

Gruppo Editoriale L’Espresso, which publishes La Repubblica and the weekly L’Espresso, last month cited the editorial initiatives as a reason that its net profit rose 47 percent last year, to 67.8 million euros, or about $82.9 million. In 2003, the two newspapers sold 34 million books, 2 million DVD’s and 1.6 million compact disks at prices ranging from 4.90 to 12.90 euros. La Repubblica itself costs 1.20 euros at the newsstand; L’Espresso costs 2.80 euros. Cost-cutting and improvements in online operations also helped raise profit, the company said.

“We thought we were going to appeal to a niche market because Italians aren’t known as being great readers,” said a spokesman for Gruppo Editoriale L’Espresso, who said company policy required anonymity.

He said the publisher expected to break even by selling 50,000 copies in the first series, but that around 500,000 copies of each of 50 volumes of 20th-century masterpieces were sold.

“It was instead an incredible success,” he said, “and created a new phenomenon for the Italian market.”

La Repubblica is now selling a six-volume set of Italian poetry from the 13th century to the present. The paper has sold about 120,000 copies of each volume at 7.90 euros a book.

If the numbers are good for newspapers’ bottom lines, they have book publishers worried. Almost half of the 100 million books sold in Italy in both 2002 and 2003 were sold with newspapers and magazines at newspaper kiosks, according to the Italian Publishers Association.

“Newspapers are no longer just vehicles for information – they’ve become a distribution system,” said Federico Motta, president of the publishers association.

Newspapers have several advantages over traditional book publishers, he said, starting with a distribution network of around 40,000 newsstands throughout Italy.

Click here for the full story. Americans, in contrast, sell books at discount superstores, such as Wal-Mart. Or now you can buy digital music at Starbucks. Not to mention those Picassos

The bottom line: The sale of culture is increasingly about the best way to mobilize notice and attention. Over the next century, expect traditional cultural intermediaries to disappear or be radically transformed. When you buy art from a traditional gallery, sales and certification are bundled together in the same institution. As the division of labor increases, we should expect sales and certification to become separate functions, performed by separate groups of people. The reality is that coffee shops, newspaper stands, Wal-Marts, or whatever are now the institutions that hold our attention. They will become our new cultural suppliers.

How bestsellers have changed

Here are some basic facts:

The popularity of religious titles has soared. Books such as Left Behind by Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins, the first in a popular series and No. 61 for the decade, used to be sold primarily in Christian bookstores. Now they’re stacked thigh-high at discount stores such as Wal-Mart.

Self-help, always a fixture of best-seller lists, is shifting the focus from improving people’s lives to improving their health as many baby boomers pass 50. [Diet books, most of all Atkins-related, have become especially popular.]

Brand-name series grabbed a growing share of the list. Chicken Soup for the Soul begat Chicken Soup for the Woman’s Soul, which begat Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul. All were among the decade’s 100 most popular titles.

With 12 novels on the list of 100, John Grisham staked out a nearly permanent spot on the weekly best-seller list. Only the titles changed. But if the familiar was popular, there were a few surprises. Previously unknown novelists such as Dan Brown (The Da Vinci Code) and Alice Sebold (The Lovely Bones) ended up among the decade’s best sellers.

Fiction, led by thrillers, staged a comeback, accounting for 72% of last year’s weekly best sellers, compared with 59% in 1998.

Here are other facts of import:

1. Never have so many books been published: in the U.S. more than 1,000 new titles a week, nearly double the rate in 1993.

2. Aggregate book sales are flat.

3. “last year the average American spent more time on the Internet (about three hours a week) than reading books (about two hours a week). And…the average American adult spent more money last year on movies, videos and DVDs ($166) than on books ($90).”

4. Bestsellers (top ten in the major categories) account for only 4% of book sales.

5. Amazon, Barnes&Noble.com and BookSense.com account for 8% of U.S. book sales.

6. Discount stores and price clubs account for 11% of U.S. book sales.

7. Humor books have fallen from 5.3% of the bestsellers market in 1995 to 0.6% today.

8. The Cliff Notes version of The Scarlet Letter outsells the real thing by 3 to 1.

9. In August dictionaries are 77% of all reference book sales. Otherwise they run less than five percent of the total.

Here is the the full story, noting that some of the facts are found in the paper edition only.

The bottom line? The book market works wonderfully. If you have any complaint, it should be with the quality of public taste.

USA Today (from Thursday) offers a list of the 100 best-selling books of the last ten years (not on-line). Once you get past Tolkien and Harry Potter, there is little to interest me. That being said, I find it easy to walk into my public libraries and every week find numerous good new books to read.

Road to Serfdom, 60th anniversay

BBC informs us that this is the 60th anniversary of the publication of Hayek’s Road to Serfdom. In memoriam, here is a fact sheet about the book.

I have always seen huge pluses and minuses in the work. On the down side, mixed economies did not lead to fascism, communism, or totalitarianism, as Hayek had feared. On the plus side, Hayek offers his strongest and clearest case for liberty. Only rarely is political decision-making about trying to do the right thing. His analysis of the dynamics of political power remains a “public choice” classic to this day.

Thanks to Ray Squitieri for the pointer.

The National Book Awards

Edward P. Jones, who ended a 10-year absence from publishing with his novel “The Known World” (Amistad/HarperCollins), won the fiction prize of the National Book Critics Circle on Thursday night in a ceremony at New School University in Greenwich Village.

These other awards were made:

¶Paul Hendrickson, “Sons of Mississippi: A Story of Race and Its Legacy” (Knopf), for general nonfiction.

¶William Taubman, “Khrushchev: The Man and His Era” (W. W. Norton), for biography-autobiography.

¶Rebecca Solnit, “River of Shadows” (Viking), a study of high-speed photography and other 19th-century technology, for criticism.

¶Susan Stewart, “Columbarium” (University of Chicago Press), for poetry.

Studs Terkel, 91, the Pulitzer Prize winning author, oral historian and self-described champion of the uncelebrated, received the Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award.

Here is the story. I had started the Jones book and it bored me, I will try again. The Taubman book on Khruschchev is first-rate.

New trends in self-publishing

Why not go with Borders, the people who sell you the books?

“It’s easy to publish your own book!” the “Borders Personal Publishing” leaflets proclaim. Pay $4.99. Take home a kit. Send in your manuscript and $199. A month or so later, presto. Ten paperback copies of your novel, memoir or cookbook arrive.

Fork over $499, and you can get the upscale “Professional Publication” option. Your book gets an International Standard Book Number, publishing’s equivalent of an ID number and is made available on Borders.com, and the Philadelphia store makes space on its shelves for five copies.

Borders is the latest traditional bookseller or publisher to branch into self-publishing using print-on-demand or P.O.D. technology. P.O.D., inheritor of the vanity press and survivor of the dot-com implosion, makes it feasible – technologically and economically – to produce one copy of a book.

Unlike e-books, which also appeared in the late 1990’s, P.O.D. self-publishing has developed into a real business, attracting involvement from the likes of Random House, Barnes & Noble and now Borders.

Forty percent of all self-published books are sold to the authors, and most of the other sixty percent are sold on-line. One company, iUniverse, has 17,000 published titles. 84 have sold more than 500 copies, and a half dozen have made it to Barnes and Noble shelves. But then again, traditional vanity presses charge you at least 8 to 10K to publish a book, with no guarantees.

Here is the full story. As Clay Shirky notes, the world is moving from the paradigm of “first filter, than publish” to “first publish, then filter.”

But does self-publishing have a bright future? Yes and no. Soon self-publishing won’t be worse than going with a mediocre press. The value of the very best certifiers will go up (in the academic market this is Harvard, Princeton, Chicago, and MIT presses, for a start), if only because the proliferation of writing makes their sorting function more important. At the same time the relative value of the middling certifiers will fall. It will become apparent they don’t offer a better product than writers operating on their own. At some point you have to ask whether the press is lending reputation to the author, or vice versa.

By the way, here is one self-published memoir which I love, the author Thelma Klein was the mother of well-known economist Daniel Klein. Yes they still have copies if you want to buy one, and they only cost a few dollars.