Category: Economics

Steve Levitt responds to critics

Read it here. Parting excerpt:

No doubt there will be future research that attempts to overturn our

evidence on legalized abortion. Perhaps they will even succeed. But

this one does not.

I’ve yet to go through the arguments of the critics, much less the response. In the interests of data centralization, leave your comments on the Freakonomics blog.

How to save for your retirement

…for most of us, it would probably be easy to save for retirement if we

were willing to live like your parents did–or at least like my parents

did. One television, no stereo, no VCR, no cable, one (used) car, six

rooms for four people, no eating out, no cell phones, no vacations

other than visiting relatives, stretching meat out with egg and bread

and noodle rings, jello as a salad, turn the light off when you leave

the room and get off the phone–it’s long distance!

Jane Galt has more. Saving is less fun than it used to be, most of all in the United States. That is one reason why we save less, or save only in fun forms, such as capital gains on our homes. The better your society at marketing and retail, the harder it is for abstinence to compete.

How much does Wal-Mart receive in government subsidies?

Uh, not that much. Matt Yglesias should receive a uh…Matt Yglesias award for the post.

Wired Ads a Leading Indicator?

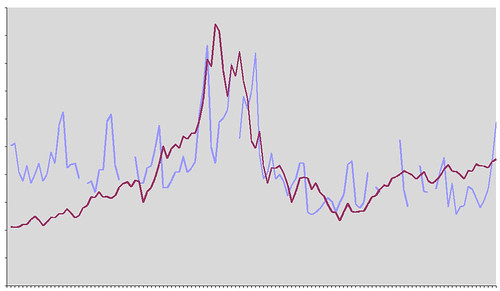

Is it time to invest in technology stocks again? Mark Frauenfelder at Boing Boing Blog points us to this graph (before getting too excited, however, I would want to detrend for seasonality, i.e. the Christmas effect):

Rich Giles made a graph that compares the page counts of past issues of Wired

with the the rise and fall of Nasdaq over the years.You’ll note that the Nasdaq (red) lags Wired’s page count (blue) by a

few months [No longer true, in the updated graph -see below – although they do seem to move together, AT]. I’m not suggesting you go an buy technology shares, but gee, I’m

thinking the reports of money pumping back into technology companies might just

be true given the big up-tick in this months page count (294).

Addendum: There were some problems with the author’s original graph. He corrected and I have reposted. The data are available here. Thanks to the Stalwart and Paul N for pointing me to the problem.

Wisdom about upward-sloping demand curves

MR has had especially good comments lately:

The problem with this thought experiment is that even if every

individual (or all but one) have an upward-sloping individual demand

curve, the market demand curve will still be downward-sloping. The

reason is, when people who seek higher prices will run out of money

faster, thus buying fewer units. So higher prices still lead to fewer

units sold — i.e., a downward-sloping market demand curve.

Or how about this:

Your curve slopes upward until it reaches the point where quantity

times price equals your wealth. From there on, it slopes down (you buy

as much as you can afford, which is less and less at higher prices).So everyone would quickly spend all their money.

Oddly, some goods might end up with demand curves that slope down in

the relevant price range– in spite of the buyers’ preferences!

Perhaps you’ve already spoken your mind, but comments are open again, in case you would like to take another crack at the problem. And remember, spent funds are recycled to sellers and do not represent the destruction of real resources.

10:30 p.m.

Tim Harford and I will be on C-Span, also with Sebastian Mallaby and Bob Hahn. And here is Tim, channeling Thomas Schelling, on why you should burn your Christmas card lists.

Nick Szabo’s blog

One of my main interests is the history of institutions, and in

particular the patterns that recur in successful institutions. These

organizational structures and security mechanisms allow naturally

suspicious strangers to interact with integrity.These patterns include tamper evidence, shared time, unforgeable costliness, separation of duties, the principle of least authority, risk sharing, and learning from our ancestors,

among many others. These patterns have been useful for centuries, and

(I can report after having spent many years working in the computer

network security field) continue to be useful in the Internet era.

Here is the blog. Here are Nick’s essays. The pointer comes from Brad DeLong. Here is Nick on The Playdough Protocols.

How fast is the economy growing?

Arnold Kling, teaming up with Robert Fogel, has the answer.

Does capital taxation hurt an economy?

Following my Econoblog debate with Max Sawicky, Kevin Drum writes:

Basically, I’m on Max’s side: I think taxation of capital should be at roughly the same level as taxation of labor income. However, I believe this mostly for reasons of social justice, and it would certainly be handy to have some rigorous economic evidence to back up my noneconomic instincts on this matter. Something juicy and simple for winning lunchtime debates with conservative friends would be best. Unfortunately, Max punts, saying only, "As you know, empirical research seldom settles arguments."

Let me repeat the chosen comparison: capital taxes vs. gasoline taxes and no subsidies for housing. That is a no-brainer. But still you might be interested in the question of capital taxes vs. labor taxes. Here are some points:

1. Supply-siders writing on capital taxation often make exaggerated claims. Even if you like their conclusions, beware.

2. Taxing dividends, corporate income, returns to savings, and capital gains all involve separate albeit related issues. I am willing to consider zero for the lot. Of that list, the corporate income tax is probably the biggest mess. The capital gains tax is the least harmful. The tax on dividends is the least well understood (in perfect markets theory, the level of dividends should not matter at all). By the way, if you are worried about noise traders, a transactions tax is a better way to address this problem than a capital gains tax.

3. The U.S. currently lacks exorbitantly high levels of capital taxation. Joel Slemrod estimates a rate of about fourteen percent, albeit with many complications and qualifications. N.B.: We lower the rate of tax on capital by engaging in crazy-quilt and distortionary adjustments. Nonetheless it is incorrect to argue "we have high rates of capital taxation and are doing fine, better than Europe." Do not confuse real and nominal tax rates.

Take the capital gains tax. Once you consider bequests and options on loss offsets, the effective rate of tax is arguably no more than five percent. But it is still set up in a screwy way. Bruce Bartlett points me to this short piece on real tax burdens on capital.

4. Peter Lindert has good arguments that favorable capital taxation has helped European economies finance their welfare states.

5. Larry Summers did the best empirical work on how abolishing capital income taxation would boost living standards.

6. Encouraging savings will have a big payoff. If you tax capital at zero, in the long run you will have much more of it. This holds in most plausible views of the world. Max’s examples aside, the supply curve for savings does not generally slope downwards; nor need you write me about various strange counterexamples from Ramsey models. Sooner or later, more capital will kick in to mean a much higher standard of living.

7. Bruce Bartlett points me to this excellent CBO study. It shows how much capital is taxed unevenly; one virtue of a zero rate is to eliminate many of those distortions in a simple way.

8. Remember those arguments about how more money doesn’t make you happier? And we are all in a rat race where we work too hard to win a negative-sum relative status game? I’ve never bought into them, but it’s funny how they suddenly stop coming from the left once the topic is capital vs. labor taxation.

9. The same excellent Slemrod paper (and he is no right-wing supply-side exaggerator) also suggests that the revenue lost from a zero rate on capital would be small. N.B.: The references to this paper are the place to start your reading on this whole topic.

10. Kevin Drum’s belief in social justice should not necessarily lead him to look for arguments for taxing capital. Even if we accept his normative views, there is the all-important question of incidence. Taxing capital can hurt labor. If you are truly keen to tax capital, this is a sign of a high time preference rate, not concern for the poor.

11. Some forms of human capital also should receive favorable tax treatment. Vouchers for primary education and state universities are two examples. I am also happy — in part for equity reasons — to subsidize human capital acquisition through an Earned Income Tax Credit.

12. What is really the difference between capital and labor? Is it simply measured elasticities? The size of each potential tax base? The greater "future orientation" of capital and the possibility for compound returns? All of the above? How much does your answer depend on whether you view capital as a "fund" or as a "collection of capital goods"?

The bottom line: It all depends on the margin. If your levels of government spending allow you to keep labor rates of taxation below 40 percent, I don’t see comparable gains from lowering tax rates on labor. If you have equity concerns, express them through other policy instruments. But if your marginal tax on labor is 65 percent and your tax rate on capital is 15 percent, cut the tax on labor first.

I know it hurts, but all of you non-right-wingers out there should consider a zero rate of taxation on capital. Comments are open.

A crash course on spontaneous order

You will find the essay here, with comments, and yes it includes Smith and Mandeville up through the moderns.

Econoblog on tax reform

Max, are you willing to raise your hand and say: "I want to in essence

double the real rate of taxation on capital income. I don’t think the

growth rate will fall"?

That is from my debate with Max Sawicky, here is the link. Go see if Max raises his hand.

Addendum: I’ve opened up comments, since Max seems to be requesting that.

Markets in everything — air rights in NYC

$430 a square foot, to buy the air rights for an unfettered view of Central Park.

Paying for Performance II

Roland Fryer’s experiment to pay school children for better grades will go into effect next year reports the New York Post.

Under the pilot, a

national testing firm will devise a series of reading and math exams to

be given to students at intervals throughout the school year.Students

will earn the cash equivalent to a quarter of their total score – $20

for scoring 80 percent, for instance – and an additional monetary

reward for improving their grades on subsequent tests….Levin

said details about the number of exams, what grades would be tested,

funding for the initiative – which would be paid for with private

donations – and how the cash will be distributed are still being

hammered out.…"There are people who are

worried about giving kids extra incentives for something that they

should intrinsically be able to do," Fryer said. "I understand that,

but there is a huge achievement gap in this country, and we have to be

proactive."

Thanks to Katie Newmark for the pointer.

Why are rental cars American cars?

Our new hire at GMU, Ilia Rainer, posed this question over lunch yesterday. Why don’t rental car companies use the superior Japanese product? Our group came up with a few hypotheses:

1. Rental car drivers consume patriotism by using the American product. Often a third party, such as a corporation, is picking up the bill. Rental car companies don’t want a "foreign" image.

2. Rental cars are (and must be) well taken care of by Hertz and others. Japanese cars perform better when maintenance is low, but with plenty of care American cars do just fine.

3. Here is a variant on #2: Rental cars have higher value on the resale market than regular used cars, given that they are well taken care of. This boosts the value of U.S. cars relative to Japanese cars, since Japanese cars will hold up anyway.

4. The fraud problem in the auto repair market is severe. If you can fix your cars yourself, at marginal cost, U.S. autos are a fine buy.

5. U.S. cars are more comfortable for long drives, which makes them better suited for the rental market. They are also better for "nature driving" out west. Japanese cars are better for daily commutes, urban driving, and stop-and-go driving, which are more likely found in your daily life and less likely relevant for the rental market.

But surely you can do better. Your thoughts? Comments are open.

Tim Harford interview

Here it is, courtesy of http://catallarchy.net. They also point our attention to some data on Ireland vs. the Scandinavian countries.