Category: Medicine

Bankrupt Data

Paul Krugman is plugging a new study suggesting that a majority of bankruptcies are due to medical expenses. HedgeFundGuy tears it up. Nice. See also Todd Zywicki’s comments.

More Transhumanism

In his excellent post yesterday on identity and transhumanism Tyler asked:

Now let’s say

your children could be one percent happier throughout their lives, but

this would mean they were totally unlike you, the parent… How many of us would choose this option?

I think the answer is more than Tyler imagines. Many poor immigrants have made exactly this choice. They come from the old country for a better life for their children and in the process their children become something strange and different from themselves, namely American. The tension between the immigrant parents, never quite learning to speak English properly or to adopt the new ways and mores, and their American children can be hearbreaking.

Transhumanism will never make as large a difference between a single generation as does immigration.

Tyler also writes "Isn’t there a collective action problem here? Everyone wants a more competitive kid but at the end humanity is very different."

True, but I think the collective action problem is actually a solution to the externality problem. Consider a slight modification of Tyler’s example.

Suppose that your children could be much happier throughout

their lives, but this would mean they were totally unlike you, the

parent.

Why would parents say no to this offer? Only because they discount the happiness of their children relative to their own – even if the children gain much more than the parents, the parents lose and they say no. And yet isn’t this monstrous?

Fortunately, change across a single generation is likely to be small so parents will say yes even though 5 or 6 or 10 generations down the line the changes will be dramatic. It’s because of this wedge effect that Fukuyama is so worried about relatively small changes today and it’s precisely for this reason that his opposition has no hope of success in a free society.

Bring on the velociraptors.

Dutch Treat

Holland’s Health Minister has proposed a system for organ donation similar to what I have called (in Entrepreneurial Economics) "no-give, no-take." Under the proposed system people who sign their organ donor cards would receive points which would raise them on the waiting list should they one day need an organ.

My main argument for no-give, no-take has always been efficiency, it would increase the incentives to donate. It’s fairness, however, especially as it intersects with the politics of immigration that is driving the change in Holland.

The Liberal VVD minister defended his proposal by pointing out that

Muslims often refuse to donate organs based on religious beliefs. This

is despite the fact they are willing to receive an organ if they are

ill. "That creates a bad feeling," he said."If you say: ‘I refuse to donate an organ because of my religion,

but I don’t want to receive one either’, than I will respect it. But I

won’t respect a one-sided attitude of receiving and not giving. I find

that problematic," Hoogervorst said.

Thanks to Dave Undis for the pointer.

Aids, Condoms and Africa

Regarding my post, The African Cliff, a number of readers wrote to me about the Catholic Church’s anti-condom teachings (and apparently in some cases mis/disinformation campaigns).

I have three reasons for thinking that Catholic teaching on condoms, whatever you might think of the substantive issue, is not a major factor in the African Aids crisis. First, Catholics in the US don’t seem to find it difficult to ignore the Church’s teachings when these are costly. Second, many African countries with high Aids rates have few Catholics. (Compare the countries in yesterday’s graph with this map of Catholic membership in Africa.) Third, couples who do not use condoms but follow Catholic teaching in regards to monogamous marriage are unlikely to contribute much to the Aids problem. It seems inconsistent, moreover, to assume that religion is strong enough to prevent men from using condoms but not strong enough to stop them from sleeping with multiple partners. Does the man having sex with a prostitute feel less guilty because he isn’t wearing a condom? (Admittedly, I don’t know enough about venial versus mortal sins to be sure about the latter.)

We hope that Marginal Revolution can be enjoyed by the whole family so I am somewhat reluctant to discuss a second hypothesis brought to my attention by Steve Sailor. Nevertheless intellectual honesty compels me to mention dry sex.

Epidemiologists are also finding that multiple concurrent sex partners are an important transmission route. Halperin and Epstein writing in the Lancet (subs. required) note:

Of increasing interest to epidemiologists is the observation that

in Africa men and women often have more than one–typically two or

perhaps three–concurrent partnerships that can overlap for months or

years. This pattern differs from that of the serial monogamy more common in

the west, or the one-off casual and commercial sexual encounters that

occur everywhere.

Morris and Kretzschmar

used mathematical modeling to compare the spread of HIV in two

populations, one in which serial monogamy was the norm and one in which

long-term concurrency was common. Although the total number of sexual

relationships was similar in both populations, HIV transmission was

much more rapid with long-term concurrency–and the resulting epidemic

was ten times greater.

It is important to understand that multiple concurrent partners does not mean more partners in a lifetime. What differs in parts of sub-Saharan Africa is the pattern and timing of sexual relations not the number of lifetime partners. (See also Sailor for a tendentious but interesting take on the why the pattern might be different in parts of Africa.)

The African Cliff

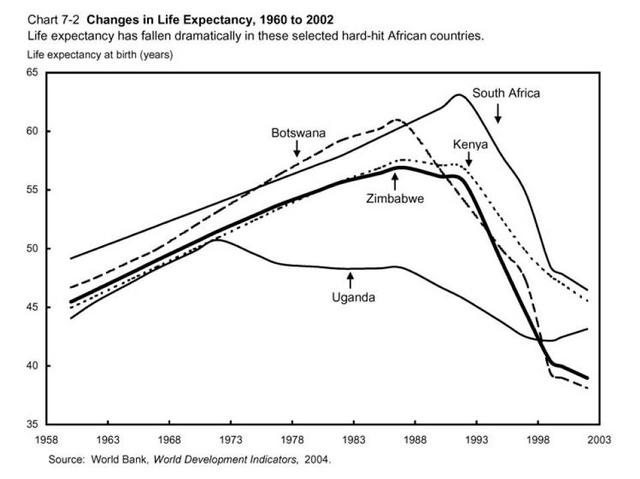

Even though I know about AIDS in Africa this figure shocked me.

What I don’t understand is why the discussion of solutions focuses so heavily on AIDS drugs when condoms are cheaper and more effective in preventing spread of the disease. And why isn’t condom use in Africa skyrocketing? (A notable exception is Uganda where AIDS rates have begun to level off due to condom use– see graph). Condoms are cheap – even if not to every African they can be easily subsidized by donor groups or governments but there is still a large condom-gap in Africa.

Note that in theory condom use could increase transmission of AIDS if it increases sex. Evidence from the US and elsewhere indicates this is unlikely in practice. Moreoever, it doesn’t explain why more condoms are not being used.

Figure from the Economic Report of the President (2005) via Ben Muse.

Brad is wrong, so is Brad

Brad DeLong quotes Brad Plummer:

[I]t really doesn’t make a difference whether you pay 40 percent of your income for private health care, or 40 percent of your income in taxes that then go to government-administered health care. I mean, yes, in one sense it makes a difference: If you think the free market is a better way of delivering health care, you’ll endorse option 1; otherwise, you’ll endorse option 2. But in the end, you’re still paying 40 percent of your income….it’s disingenuous to say, "Oh no! America’s doomed! We’re going to have

to raise taxes massively in the future in order to afford things we’d

be spending a good chunk of our income on anyway!"

Brad DeLong writes "Brad is absolutely right. (I like the way

that sentence sounds: I wish *I* heard it more often from others.)"

Sorry Brad (and Brad), I’d like to oblige but there is a big difference between spending 40 percent of your own income on health and having 40 percent of your income taken in taxes and spent on health even if we assume that the spending is on exactly the same thing. The 40 percent of your income spent on health is a benefit of work, a reason to work harder, but the 40 percent taken in taxes is a cost of work that creates a dead weight loss. Moreover, at 40 percent plus the dead weight loss is going to be big.

To make the problem with Brad P.’s thought experiment clear suppose that we documented exactly how everyone spent their yearly income. Now we tax everyone 100 percent and provide them with exactly what they were buying before. Nothing changes, right? Wrong. At 100 percent tax there is no longer any incentive to work – thus no one works and nothing is provided. Everything changes.

Brain Drained

Two weeks ago I posted on the brain drain at the NIH brought about by new draconian rules on so-called "conflicts of interest" between NIH workers and outside interests. I suggested that the policy was a mistake but we now learn from the Washington Post that it is a stupid mistake.

The unexpected finding that as much as 80 percent of the seeming

improprieties were actually the result of errors by government

investigators has undermined the rationale behind NIH Director Elias A.

Zerhouni’s recent decision to impose severe restrictions on the

personal activities and finances of all of the agency’s more than 5,000

employees…

The story is simple. The government asked the pharmaceutical companies for the names of all NIH scientists with whom they had consulting operations and they asked the NIH for a similar list. Comparing the two lists they found about 100 names on the pharmaceutical list which were not on the NIH list and then jumped to the conclusion that these 100 people were lying. After months of investigation during which many people’s lives have been turned upside down it turns out that one list included 2004 but the other did not, some of the "John Smiths" on the pharmaceutical list were incorrectly identified with "John Smiths" at the NIH, the pharmaceutical companies didn’t use the same definition of consulting as the NIH etc. Keystone cops.

And here is an example of the new law in practice.

One scientist who, under the new rules, was informed he could not

accept an unpaid adjunct professorship at Johns Hopkins University was

told he might be unduly influenced in favor of the university because

the appointment came with free campus parking…

Richard Posner on Medicare

As a matter of economic principle (and I think social justice as well), Medicare should be abolished. Then the principal government medical-payment program would be Medicaid, a means-based system of social insurance that is part of the safety net for the indigent. Were Medicare abolished, the nonpoor would finance health care in their old age by buying health insurance when they were young. Insurance companies would sell policies with generous deductible and copayment provisions in order to discourage frivolous expenditures on health care and induce careful shopping among health-care providers. The nonpoor could be required to purchase health insurance in order to prevent them from free riding on family or charitable institutions in the event they needed a medical treatment that they could not afford to pay for. People who had chronic illnesses or other conditions that would deter medical insurers from writing insurance for them at affordable rates might be placed in “assigned risk” pools, as in the case of high-risk drivers, and allowed to buy insurance at rates only moderately higher than those charged healthy people; this would amount to a modest subsidy of the unhealthy by the healthy. Economists are puzzled by the very low deductibles in Medicare (including the prescription-drug benefit–the annual deductible is only $250). Almost everyone can pay the first few hundred dollars of a medical bill; it is the huge bills that people need insurance against in order to preserve their standard of living in the face of such a bill. But government will not tolerate high deductibles when it is paying for medical care, because the higher the deductible the fewer the claims, and the fewer the claims the less sense people have that they are benefiting from the system. They pay in taxes and premiums but rarely get a return and so rarely are reminded of the government’s generosity to them. People are quite happy to pay fire-insurance premiums their whole life without ever filing a claim, but politicians believe that the public will not support a government insurance program–and be grateful to the politicians for it–unless the program produces frequent payouts. If Medicare were abolished, the insurance that replaced it would be cheaper because it probably would feature higher deductibles…

Here is the whole post. Here is Gary Becker’s response.

My take: I should defer to my epistemic superiors, and I do not have a better reform idea. My main worry is that a means-tested system for health care aid will imply significantly higher real marginal tax rates. My second worry is that people who didn’t buy health insurance would end up on the public dole in any case.

The $800 million dollar pill?

The research by DiMasi et al. showing that the cost of the average new drug (new chemical entity) is about $802 million dollars is controversial with many people suggesting the results were doctored. A new paper, Estimating the Costs of New Drug Development: Is it really $802m?, by two economists at the Federal Trade Commission, replicates that research using somewhat different data and they indeed find that DiMasi et al. are wrong. The average new drug does not cost $802…it costs between $839 and $868 million.

An interesting aspect of the new study is that the authors break down development costs by drug category finding that AIDS drugs, for example, cost considerably less than average. Why? The authors suggest that AIDS drugs have been regulated less severely than other drugs resulting in lower costs as well as quicker times to market.

Brain Immaturity

By most physical measures, teenagers should be the world’s best

drivers. Their muscles are supple, their reflexes quick, their senses

at a lifetime peak. Yet car crashes kill more of them than any other

cause — a problem, some researchers believe, that is rooted in the

adolescent brain.A National Institutes of Health study suggests that the region of

the brain that inhibits risky behavior is not fully formed until age

25, a finding with implications for a host of policies, including the

nation’s driving laws.

The results are interesting if a tad obvious. I am bothered, however, by how much of this type of research is suffused with a normative bias. Why is taking risks always connected with brain immaturity? Why not say brain atrophy makes people stodgy and boring? Could it be that the researchers are not teenagers?

This results also leads me to wonder about all those experimental economics studies done on university students.

Thanks to Carl Close for the pointer.

Brain Drain at the NIH?

Last week the NIH announced drastic new rules restricting employees, and their spouses and dependents, from stock holdings in drug, biotech and other companies with significant medical divisions. Consulting, lecturing and other outside income is also severely restricted. Even most prizes and awards with money are now forbidden (the Nobel is an exception). NIH employees are furious.

Word on the street is that universities, including GMU, are receiving a flood of applications from talented scientists. (Perhaps the NIH should have consulted with some economists who might have explained the concepts of opportunity costs and compensating differentials).

No doubt there were some conflicts of interest and some abuses but there were also virtues in the old system. The free flow of scientists to and from commercial and government research is a key part of what made Washington and Maryland’s biotech sector succesful. Moreover, as Steve Pearlstein notes, it wasn’t that long ago that this free flow of people, ideas and money was encouraged, precisely in order to get the scientists out of their ivory tower and into the real world of medical need. Expect less from the NIH in the future.

Medical mistakes

More people die from medical mistakes each year than from highway accidents, breast cancer, or AIDS and yet physicians still resist and the public does not demand even simple reforms.

The New England Journal of Medicine, for example, has just published another study, as if we needed it, showing that interns who are kept awake for 30 hours straight

are a danger to themselves and innocent bystanders as well as to patients:

Researchers found that interns more than doubled their risk of getting into a

car accident after being on call, a stint that meant working for 32 consecutive

hours with only two or three hours of sleep, on average. Interns were also

nearly six times as likely to report nearly having an accident on their way

home.….The researchers say those limits don’t give doctors enough time to sleep.

A study published last fall, also in the New England Journal, found that interns

who spent every third night working in the intensive care unit made 36% more

medical errors than interns who kept less onerous schedules. They also made

serious diagnostic errors 5.6 times as often as their well-rested counterparts,

the study found.

I will just quote Kevin Drum on this:

I’ve heard a litany of defenses of this practice from senior medical folks,

and they couldn’t sound more lame if they tried. They sound like nothing so much

as a bunch of 50s frat boys defending hazing after some freshman has been found

dead in an arroyo somewhere.

It’s unbelievable that this system has continued as long as it has and

unbelievable that it continues to be defended. Do we really need studies to tell

us that people who have been awake for 30 consecutive hours probably aren’t

making very good decisions? And that both patients and others are suffering from

this?Would you want your mother to be looked after by a trainee who’s been

on her feet for 30 hours? I wouldn’t.

How to fight AIDS in Africa

A new paper, "Sexually Transmitted Infections, Sexual Behavior and the HIV/AIDS Epidemic"

by Harvard economics graduate student Emily Oster, asks why prevalence

rates for HIV/AIDS are ten to fifteen times higher in Africa than in

the United States. Using a simple model that decomposes infection

levels into differences in sexual behavior and differences in

transmission rates, she attributes the entire difference in HIV

prevalence between the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa to

differences in transmission rates. The intuition, as she writes, is

that "Higher transmission rates produce more infections this period,

and each new infected person can infect people next period, so the

result of a higher transmission rate is multiplied many times over."One

of the implications of her findings is that lowering transmission rates

by targeting STDs is more cost effective than trying to reduce HIV

prevalence using expensive antiretrovirals or education programs aimed

at changing behavior.

Read more here.

Are we spending our health care dollars effectively?

(I am quoting from Randall’s email here, Typepad won’t let me indent beneath the fold…)

"A) For anyone who is dying the lack of FDA approval should not prevent the use of a treatment.

While I would favor complete revocation of FDA ability to keep drugs off the market that is not going to fly politically. But selling a more limited change where those with, say, a projected 12 month or 24 month life expectancy get a basic "I’m free of the FDA tyranny" card would accelerate drug development. Phase I and Phase II drugs would be more widely available….

D) The coercive power of the state should force a percentage of all income to go into medical spending accounts.

The goal here is two fold:

– Decrease the number of people who need state medical funding.

– Also, increase the amount of medical treatment purchases that are paid directly by patients. That will increase market forces in medicine.

E) Self-employed people should be able to buy medical insurance pre-tax.

F) People should be able to make tax deductable donations into medical spending accounts for their future children before the children are conceived. Then the money should be usable to buy medical catastrophe insurance against the possibility of birth defects and also for more mundane medical care.

G) People should be able to bring their own medical insurance policies with them to a job and have their employers pay on those policies rather than on the employer’s group policy.

That way a person could move around between jobs and never reach a state where their COBRA runs out and a pre-existing condition makes them uninsurable (assuming they can even afford to make COBRA payments while unemployed). The way things stand now the tax law forces people to go uninsured between jobs. When you have no income coming in you suddenly have to try to get coverage. That problem must be fixed.

H) Medical records should be made electronic and more widely shareable by researchers that most medical patients effectively become enrolled in "virtual" medical trials."

In praise of impersonal medicine

Many people complain that medicine is too impersonal. I think it is not impersonal enough. I have nothing against my physician (a local magazine says he is one of the best in the area) but I would prefer to be diagnosed by a computer. A typical physician spends most of the day playing twenty questions.

Where does it hurt? Do you have a cough? How high is the patient’s

blood pressure? But an expert system can play twenty questions better than most people. An expert system can use the best knowledge in the field, it can stay current with the journals, and it never forgets.

Consider how many people die because physicians forget the basics. Gina Kolata reports on a Medicare program to rate hospitals on the quality of care provided in the treatment of heart attacks, heart failure and pneumonia – these three areas chosen because there are standard, clinically proven, treatments that everyone agrees are highly beneficial.

At Duke University’s hospital, for example, when patients arrived

short of breath, feverish and suffering from pneumonia, their doctors

monitored their blood oxygen levels and put them on ventilators, if

necessary, to help them breathe.But they forgot something:

patients who were elderly or had a chronic illness like emphysema or

heart disease should have been given a pneumonia vaccine to protect

them against future bouts with bacterial pneumonia, a major killer.

None were.All bacterial pneumonia patients should also get antibiotics within four hours of admission. But at Duke, fewer than half did.

The

doctors learned about their lapses when the hospital sent its data to

Medicare. And they were aghast. They had neglected – in most cases

simply forgotten – the very simple treatments that can make the biggest

difference in how patients feel or how long they live.

…[Similarly, the] hospitals were asked how often their heart attack

patients got aspirin when they arrived (that alone can cut the death

rate by 23 percent). When they were discharged, did they also get a

statin to lower cholesterol levels? Nearly all should, with the

exception of patients who have had a bad reaction to a statin and those

rare patients with very low cholesterol levels. Did they get a beta

blocker?Once hospitals learned their score, it was up to them what to do.

Over the next year, ones that improved in these measures saw their

patient mortality from all causes fall by 40 percent. Those whose

compliance scores did not change had no change in their mortality rate,

and those whose performance fell had increases in their mortality rates."Those are the most remarkable data I have ever seen," said Dr. Eric

Peterson, the Duke researcher who directed the study and has reported

on it at medical meetings.

Unfortunately, we (doctors and patients) have a model in our head of the nearly omniscient doctor carefully attending to the needs of every patient on an individualized basis – medicine as craft. Instead what we need is medicine by the numbers. But doctors don’t like being told what to do.

"We tried to come up with a standardized order set," with all the

measures that Medicare was asking about, Dr. Gross said. "But the

doctors didn’t want to use the sheet," insisting they would just

remember those items. Then they forgot.

The solution, Dr. Gross said, was to assign specially trained nurses

to see what care was provided and remind doctors when important steps

were omitted. The result was immediate improvement, Dr. Gross said,

even in items not on Medicare’s list.

The nurses, in effect, are being trained to follow standardized procedures, just as does an expert system.

Thanks to the John Palmer, The Econoclast, for the link.