Category: Political Science

Perceptive Plato

My colleague Bryan Caplan has emphasized for years that people treat politics differently from other topics. This has seemed to me a deep insight, and I’ve long puzzled over it. Wouldn’t you know it, Plato noticed the same thing (Protagoras, translated by Benjamin Jowet):

Now I observe that when we are met together in the assembly, and the matter in hand relates to building, the builders are summoned as advisers; … And if some person offers to give them advice who is not supposed by them to have any skill in the art, even though he be good-looking, and rich, and noble, they will not listen to him, but laugh … But when the question is an affair of state, then everybody is free to have a say–carpenter, tinker, … and no one reproaches him, as in the former case, with not having learned, and having no teacher, and yet giving advice; evidently because they are under the impression that this sort of knowledge cannot be taught….

Our human willingness to have confident opinions on topics where we are poorly informed seems to me a key problem in politics.

You are happier when your party wins

The unjustly-banned-in UAE Will Wilkinson directs our attention to an interesting paper:

We include in our partisan happiness equations a variable that measures

the ideological position of the government in power. It indicates that

when the government leans more to the right ideologically, right-wing

individuals tick up their happiness scores. In the same periods,

left-wing individuals declare themselves to be more dissatisfied with

their lives. The size of the coefficient is large and highly

significant.

My favorite hypothesis is that coalitional success enters directly into

the welfare function. Now, this is fascinating for all sorts of

reasons. For instance, it would seem, then, that the need to maintain a

distinct and coherent coalitional identity will limit median-voter

convergence…The general application of this kind of thinking is that partisans will

try to convince their side that being out of power is really

depressing, with the result that no matter who is in power, half the

population is really depressed.

My take: Government funding of the arts is one example. In many countries the mere existence of government arts programs does more for citizen utility than the results of those programs. People enjoy being affiliated with a government that has artistic or aesthetic aspirations. I don’t intend this as a reductio ad absurdum. It could well be that arts spending is a relatively cheap way of "buying off" these feelings. For instance, the relevant alternative might be an obnoxious form of patriotism, or perhaps higher levels of government spending on more costly (i.e., universal) areas.

That being said, I am not convinced by the result more generally. You are supposed to pretend you care about your candidate, but this might be a framing effect. You adopt a happy or unhappy stance, partly to signal group loyalties, but your daily happiness is fairly robust to who delivers the State of the Union addresss (policy effects aside, of course).

Look at me, I am happy, and the U.S. does not have Donald Brash running for Prime Minister.

Iraq and consequentialism: what is the marginal product of war?

Many anti-war criticisms cite the badness of current events without asking how much of that badness was due to happen anyway. To clarify, let us consider three arguments against the war:

1. U.S. behavior was wrong on deontological grounds, namely we should not kill innocents (and tax others to pay for this killing), even when the long-run consequences are good. Of course if this is true, the arguments stops there. Furthermore it would be irrelevant — at least for judging rightness — whether the war/reconstruction was going well or not. So I doubt if this is all of the anti-war critique; let us move on to the rest.

2. It is not worth killing innocents to overthrow a tyranny. This will also stop the argument, but most anti-war critics don’t hold this view. It would be hard to defend the rise of the West, or Allied participation in World War II, for instance.

Now consider #3:

3. The war is going badly.

The correct marginal question, however, compares the current badness to the badness which would have resulted after the reign of Saddam (or his sons? grandsons?) ended, however that might have happened. Today we see many signals that things are going badly. But most of those signals also imply that things would have gone very badly under the alternative scenario for Saddam’s fall. A civil war, for instance, may well have happened anyway, albeit later.

One might argue that U.S. participation makes an Iraqi civil war much worse than otherwise (perhaps the presence of U.S. forces motivates insurgents). But I don’t find this convincing. First, a civil war could be much worse without the U.S. presence (keep in mind the alternative scenario also involves many years of continued sanctions, or what Saddam would have done without sanctions, plus further suffering under Saddam). Second, the correct cost of the war — at least to the Iraqis — would be this difference in outcomes, not the current absolute level of badness.

The pro-war right seems keen to argue that much of the insurgency is foreign fighters. This in reality weakens their case, as it opens the possibility that the U.S. role drew in these forces. Insofar as the insurgents are Sunnis, fighting for domestic control, it is more likely they would have been fighting anyway, with or without the U.S. involved. That would strengthen a consequentialist case for the war.

It also might be argued there is intrinsic value in postponing a civil war, although this I would dispute.

Relying only on #1 is not so popular among anti-war forces, even if it is a good argument. It feels anti-patriotic to many people. Thus a huge burden gets put on #3. But citing #3 has less oomph than is commonly supposed. The worse things get, the more we can conclude they would have been very bad — sooner or later — in any case. And I’ve yet to be convinced that an Iraqi civil war — without the U.S. involved — would turn out so much better for the Iraqis.

There is of course the separate question of what is good for the U.S. and for other countries besides Iraq. If you think Iraq will go badly no matter what, those considerations may well be decisive. But it sounds selfish and defeatist to cite those arguments alone, so we are again left with anti-war cases which do not make complete sense.

Addendum: Jane Galt recently surveyed some recent blogosphere arguments about Iraq and consequentialism.

The “Failed States” index

I am surprised to see Ivory Coast as the very worst, my pick, the "Democratic" Republic of the Congo only manages to take second place. And Guatemala, for all its problems, should not be five places "more failed" than Lebanon. Still this is an interesting data source, click the colored box links at the top of the main page to see maps and the like.

A critic on Critical Mass

I recently finished Philip Ball’s Critical Mass.

The bad news: it’s twice as long as it needs to be and his criticisms

of economics are rather odd (no, ability to forecast share prices is not the

test of the subject’s validity). The good news: it’s packed full of fun

stuff about the relevance of various physical and agent-based modelling

techniques to the social sciences. Even better, you can read Ball’s own

summary and find out whether you like it.

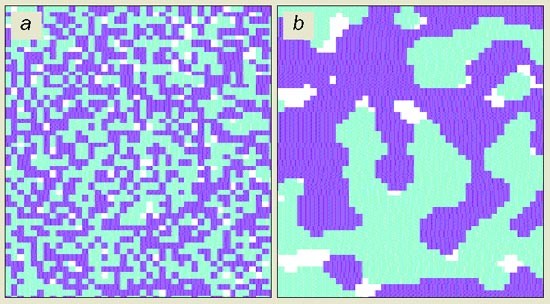

Thomas Schelling was there first again with

his chessboard model of racial segregation. The bottom line: racial

preferences which would seem to accommodate mixed neighbourhoods turn

out to lead to extreme segregation, as shown in (b) below.

Robert Axtell, one of the founders of the Sugarscape agent-based modelling system, predicts that within a few years we will be able to run models with billions of agents, rather than Schelling’s 50 or so. Artificial worlds beckon.

Peru Facts of the Day

It’s easy to rent a motorcycle in Peru, unlike in the United States where liability fears have made this almost impossible. On the other hand, I would not want to drive a car let alone a motorcycle in Peru. These two facts may well be related – I will let you work out the model.

It would have suited my biases to report that the only Che Guevara T-shirts I have seen were on tourists. But while this may be true in the cities it is not true in the countryside where it is easy to spot El Comandante. Guevara spoke to the people and they are still listening.

My tour guide, an Andean, had nothing good to say about the Spanish. Combine this with the last fact and we see that Peru continues to be deeply divided along racial lines, regardless of how much one hears about mestizo.

What is government anyway? A parable from Singapore

Yes Singapore has developed rapidly through the use of market incentives, but there is much government planning here as well. Every food stall gets a letter grade for its cleanliness, which must be displayed prominently. More significantly, land planning has been extensive, and yes the government decides where the food stalls (and just about everything else) will go.

But why do we call this government? Let us say that way back when, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew had homesteaded the territory of Singapore in proper Lockean fashion. He then wrote a contract welcoming people (all subsequent migrants, but not everyone) to live there, provided they agree to various rules and regulations, including of course Singaporean land planning, not to mention the ban on oral sex. This would then count as "the market," presumably.

Should we then think that such planning is more (or perhaps less) efficient, because it is now "the market" instead of "government"? But why should our evaluation depend on the murky details of past history? What is really the difference between market and government anyway? Can we in any case think of Singapore as a very well planned corporation, albeit with some uptight morals at times?

When we do public choice theory, is it really the government we are criticizing? Or is our true target something like "excessively large land parcels," regardless of their historical origin?

Gustav de Molinari on-line

Alas, my location prevents me from reading these recently-translated essays. But Gustav de Molinari (Belgium) was one of the best and most forceful classical liberals of the nineteenth century. He is also known for inventing the idea of libertarian anarchism, although I believe he repudiated it later in his life. The links include a biography.

Banned in the United Arab Emirates

Aid for Liberia

In the wake of the G8 summit in Gleneagles earlier this month, it seems appropriate to comment on the possible uses of aid to Liberia. At the very least, it would be nice to be able to examine the use of past official aid to Liberia. Unfortunately, any efforts in this direction are merely speculation.

The World Bank’s Africa Quick Query indicates that very little official international aid made its way to Liberia over the last 5 years of the Taylor regime. From 1999 to 2003, the aid figure ranges from $12 to $32 per capita. After spending a week in Liberia in each of the past two summers, it seems obvious to me that any aid received by former "President" Charles Taylor was mis-appropriated to his own use of physically and militarily mitigating opposition. For obvious reasons, this cannot be proved. Clearly, the funds were not spent on infrastructure. Electricity has yet to be restored (it has been out since Taylor took over in 1989), and all "roads" are painfully in disrepair.

Dollars for Guns

When the UN entered Liberia in September 2003, they instituted a voluntary disarmament program. The program specified that ex-combatants could turn in their guns for $300 and a free education (completion of high school or a choice between various trade schools). The $300 alone is a significant figure, as it is more than double the per capita gross national income. From outside Liberia, this program appeared to be successful. Kofi Annan ended the voluntary disarmament in June 2005.

With no official data to support their claims, many Liberians feel that the program was a disaster, and that all of the significant factions still have plenty of arms. The problems they cite are not surprising to an economist:

- Many guns were imported to Liberia to cash in on the $300, a price well above market-clearing.

-

UN military personnel, enjoying their immense power, actually declined guns in several parts of the country, in order that their assignment in Liberia might last longer.

Will the violence return after the elections in October? Liberians seem to be split on this. Given that there are currently 52 candidates for President, most citizens will be disappointed with the outcome.

Indian Forecast Error

India receives 90% of its rain during monsoon season so forecasting monsoons is critical for productive farming. Fortunately, according to an article in Nature (subs. req.), the Indian Meteorological Department has found a way to make its forecast better than any other available – they have suppresed publication of the other forecasts. The Indian government says this is necessary to prevent "confusion."

The main competitor to the government’s statistical model, which has not reduced its forecast error in 70 years, is from an Institute based in Bangalore which uses a climate model. The Institute and government forecasts can differ dramatically. The Institute, for example, forecast that rainfall would be 34% below average in June and 12% below average in July while the government forecast "normal or above normal rains."

The rainfall in June? 35% below average. No confusion about that.

Thanks to Robin Hanson for the pointer.

Class Struggle – Fun for the Whole Family

The goal of Class Struggle is to teach people about how capitalism really works, at least according to Marxist theory. Each player plays a class (Workers, Capitalists, Farmers, etc.) because individuals aren’t the real players in capitalist societies. Each class moves towards the center of the board collecting assets and suffering penalties. The strategy is to accumulate as many assets as you can until the Revolution arrives. If you have the most assets when the Revolution comes, you win the game.

The game isn’t terribly fun to play, as one would expect from a game emphasizing oppression, unfairness and struggle. But much fun can be had reading the rules and the “chance” cards that give you assets. For example, the expanded “Full Rules” for deciding who gets to play the Capitalist class are designed to show players unfairness towards women and ethnic minorities: “Full Rules calls for the following: beginning with the lightest White male and ending with the darkest Black female, everyone takes turns with the Genetic die to see who throws capitalist class first.” I’m proud to say that I’ve won a few games, despite my modest disadvantage as a Latino male.

The chance cards are great fun. These two examples are for the Capitalist class:

-

“You are caught feeling sorry for the Workers. Victory in class struggle comes to people who think about their own class. Miss two turns at the dice.”

-

“Paperback edition of Marx/Engels Collected Writings (100 volumes) sweeps the country. Your days are numbered. 2 debits.”

These are for the Workers:

-

“Workers finally understand that with America’s wealth and democratic traditions, socialism here will be different than what exists in Russia and China. A biggie – worth 5 assets.”

-

“Together with your fellow workers, you have occupied your factory and locked your boss in the toilet. Capitalists miss 2 turns at the dice.”

These two chance cards are counter-Marginal Revolutionary:

-

“All your propaganda says a person is free when the Government lets him alone. But almost everything one wants to do or have costs money, so only Capitalists are really free.”

-

“You publish an ‘educational’ booklet to explain that in capitalism people – as consumers – vote for what they want with their dollars. You neglect to mention that in most industries, a few firms without any effective competition decide what to produce and what to charge, or that Capitalists who have the most dollars have the most votes. Give each class in the game 1 asset so they have money to buy your booklet.”

The game has other fun rules like the nuclear showdown option: if capitalists push the button, no one wins! Bertell Ollman might be interested in knowing copies are selling for about $15 on Ebay.

Unocal and China

Michael Higgins who blogs at Chocolate and Gold Coins but is writing in the comments section of Crooked Timber asks a good question about the CNOOC bid.

If Unocal went out of business, would we have cared? If China had spent $10

billion on new tanks, would we be quaking in our boots? (I’m glad they are not

doing this). But if neither happens but instead one Chinese company buys Unocal

and keeps their employees employed, we should be concerned?

Although I didn’t get into this in my original post, it’s also not clear to me what we gain by "owning" Unocal. If the assets of Unocal are in America or an ally then CNOOCs bid gives us greater power over China not less. If the assets are in Asia then in the event of a major conflict we would have to use the military to control the assets whether we own them or not. Steve Carr, also writing in the comments section of Crooked Timber, expresses this point well.

The United States doesn’t own, in any sense, Unocal’s reserves–the vast majority

of which are, by the way, in Asia. So it’s not losing anything, because it

doesn’t have anything. If, in this imaginary future that Krugman is conjuring,

the US wants those reserves, it will have to take them by force–first

nationalizing Unocal (or whatever American company comes along to pick up Unocal

if the CNOOC bid is dropped) and then seizing and

defending the reserves militarily against the Chinese (who, in Krugman’s model,

will presumably be trying to take them). If Unocal is bought by CNOOC, and we want the reserves, we’ll again have to take them

by force from a public company. The second seems mildly more difficult than the

first, but in both cases you’re talking about a massive use of military force to

secure energy resources. If we do end up in that future, I have a hard time

believing that who owns the deed to the natural-gas fields in Indonesia is going

to make much of a difference to anyone.There is, then, no real downside (in strategic terms) to letting the deal go

through. But there’s a real downside to blocking it: alienating China, making it

clear to them that we perceive them as an enemy, looking like hypocrites in the

eyes of the world, interfering with rights of Unocal shareholders, etc.

Other good comments from Tino at Truck and Barter.

Krugman: Illiberal Demagogue

Paul Krugman used to be a liberal economist; no longer. His abandonment of economics has long been plain, Krugman’s abandonment of liberalism was announced in yesterday’s commentary on China.

What really upset me about Krugman’s column is not the bizarre economics but the illiberal politics. In the last twenty years China’s economic growth has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and nearly unspeakable deprivation. China’s abandonment of communism is one of the great humanitarian events of all time. And what does Krugman have to say about this improvement in well being? (I paraphrase).

‘Watch out. Now is the time to panic. Their gain is your loss.’

It’s hard to over-estimate how awful Krugman’s column is. Consider this:

China, unlike Japan, really does seem to be emerging as America’s strategic rival and a competitor for scarce resources…

‘Strategic rival’ is the kind of term that would-be Metternichs throw about to impress their girlfriends but what does it mean? Everyone is a competitor for scarce resources. Even those nice Canadians compete with Americans for scarce resources. Are Canadians a strategic rival to be feared?

The real question is how do rivals compete? Do they compete with war or by trade? China is moving from the former to the latter but shockingly Krugman prefers the former. Exaggeration? Consider this statement:

…the Chinese government might want to control [Unocal] if it envisions a sort of

"great game" in which major economic powers scramble for access to

far-flung oil and natural gas reserves. (Buying a company is a lot

cheaper, in lives and money, than invading an oil-producing country.

So what does Krugman recommend? Blocking the bid for Unocal. In other words, support China’s fear that they may be cut off from oil and encourage the invasion of an oil-producing country.

Nothing can harm the prospects for world peace more than the vicious

idea that we do better when they do worse. The Chinese and Americans people already have enough mercantilists,

imperialists and “national greatness” warriors pushing them towards conflict, what we need on this issue are liberal economists like the wise Brad DeLong who writes:

It is very important for the late-twenty first century national

security of the United States that, fifty years from now,

schoolchildren in India and China be taught that America is their

friend, that it did all it could to help them become rich. It is very

important that they not be taught that America wishes that they were

still barefoot and powerless, and has done all it can to keep them so.

How is it that Brad DeLong and I should agree so completely? It is because neither of us has forgotten our heritage as economists. Here then is the enlightened humanity and wisdom of the first liberal economist.

Each nation foresees, or imagines it

foresees, its own subjugation in the increasing power and

aggrandisement of any of its neighbours; and the mean principle of

national prejudice is often founded upon the noble one of the love of

our own country. The sentence with which the elder Cato is said to have

concluded every speech which he made in the senate, whatever might be

the subject, ‘It is my opinion likewise that Carthage ought to be destroyed,’

was the natural expression of the savage patriotism of a strong but

coarse mind, enraged almost to madness against a foreign nation from

which his own had suffered so much. The more humane sentence with which

Scipio Nasica is said to have concluded all his speeches, ‘It is my opinion likewise that Carthage ought not to be destroyed,’

was the liberal expression of a more enlarged and enlightened mind, who

felt no aversion to the prosperity even of an old enemy, when reduced

to a state which could no longer be formidable to Rome. France and

England may each of them have some reason to dread the increase of the

naval and military power of the other; but for either of them to envy

the internal happiness and prosperity of the other, the cultivation of

its lands, the advancement of its manufactures, the increase of its

commerce, the security and number of its ports and harbours, its

proficiency in all the liberal arts and sciences, is surely beneath the

dignity of two such great nations. These are all real improvements of

the world we live in. Mankind are benefited, human nature is ennobled

by them.