Results for “corporate tax” 243 found

Problems with destination-based corporate taxes and the Ryan blueprint

That is a recent paper by Reuven S. Avi-Yonah and Kimberly Clausing. It has content throughout, but this struck me as the most interesting section:

1. A U.S. pharmaceutical with foreign subsidiaries could develop its intellectual property in the United States (claiming deductions for wages, overhead and R&D), and then sell (i.e., export) the foreign rights to its Irish subsidiary (at the highest price possible). The proceeds would not be taxable. Ireland would allow that subsidiary to amortize its purchase price. This creates tax benefits in each jurisdiction by reason of the different regimes. If the Irish subsidiary manufactures drugs, the profits could be distributed up to the U.S. parent tax-free under a territorial system. If the Irish subsidiary is in danger of becoming profitable for Irish tax purposes, the U.S. parent would just sell it more IP.

2. If an Irish parent owns a U.S. subsidiary, the Irish parent can issue debt to fund the purchases of the IP. The U.S. subsidiary then invests the cash to generate more IP (expensing all equipment and deducting all salaries) and sells the IP to its parent.

3. If an Irish parent has purchased the U.S. IP rights, it would not want to license the rights to the U.S. subsidiary (income for Irish parent under Irish tax law and no deduction for U.S. subsidiary). So it just contributes the rights to another U.S. subsidiary. Could the U.S. subsidiary amortize the parent’s basis under the Blueprint? When one U.S. subsidiary licenses to another, no net tax would be paid. Any royalties would be taxable to the licensor but deductible for the payor.

4. How does the Blueprint work for services? If a U.S. hedge fund manager provides services to an offshore hedge fund, is that considered an export that is tax exempt? What if the U.S. manager develops a trading algorithm and sells it (or licenses) it to an offshore hedge fund? Are the proceeds and royalties exempt? If so, then the hedge fund becomes a giant tax shelter to the manager, because he would not pay 25% on this income–he would pay zero, with no further tax. This is much better than the current carried interest provision, which has attracted bipartisan condemnation because it enables individuals with income of many millions to pay a reduced rate. The Blueprint result is much worse.

What is the real rate of corporate taxation in the United States?

The inclusion of taxes both at the corporate level and on dividends changes our perspective on which countries are high tax and which are low tax. For example, Ireland has the lowest statutory corporate tax rate among O.E.C.D. countries, yet is still a relatively high-tax country because of the high tax rate it imposes on dividends. By contrast, Japan has the highest statutory corporate tax rate but only the 12th highest overall rate because it has one of the lowest tax rates on dividends.

Those advocating a cut in the corporate tax rate today generally ignore the tax on dividends, as well as many other provisions of United States and foreign tax law that may reduce the effective tax rate well below the statutory rate.

A recent study found that only 25 percent of the largest American corporations pay anywhere close to the statutory corporate tax rate of 35 percent on their earnings, while 40 percent pay less than half that rate.

Indeed, General Electric, the nation’s largest corporation, paid no federal corporate taxes in the United States in 2010, according to a report in The New York Times.

…while it may be a good idea to reduce the corporate tax rate as part of a tax reform package, the idea that this will jump-start growth is nonsense.

The latest wisdom on corporate income tax cuts

A corporate income tax cut leads to a sustained increase in GDP and productivity, with peak effects between five and eight years. R&D spending and capital investment display hump-shaped responses while hours worked and employment are much less affected.

That is from a new NBER working paper by James Cloyne, Joseba Martinez, Haroon Mumtaz, and Paolo Surico. You will hear many economists, including Paul Krugman, tell you that the Trump corporate tax cuts were a failure. It would be more accurate to say that we still do not know how effective they will be, noting that the pandemic may have extended the “five and eight years” benchmark a bit. And it would be more accurate to report that the best available science indicates the tax cuts stand a good chance of succeeding. See this earlier research, in top-tiered outlets, and also this.

What is the incidence of the corporate income tax?

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman seem to think the correct answer is to assume that there is no substitution away from capital or from the corporate sector:

This paper proposes a new way to do distributional tax incidence better connected with tax theory. It is crucial to distinguish current distributional analysis from tax reform distributional analysis. Current distributional analysis shows the current tax burden by income groups and should assign taxes on each economic factor without including behavioral responses: taxes on labor should fall on labor earners, taxes on capital on the corresponding asset owners, and taxes on consumption on consumers. This allows to distribute both pre-tax and post-tax current incomes and measure the economically relevant tax wedges on each factor without having to specify behavioral responses. Tax reform distributional analysis shows the impact of a tax reform and should describe the effect on pre-tax incomes, post-tax incomes, and taxes paid by income group separately and factoring in potential behavioral responses. Various scenarios can be considered given the uncertainty in behavioral responses. We illustrate our methodology using a simple neo-classical model of labor and capital taxation.

No Western fiscal authority I have heard of thinks of tax incidence in these terms.

There is an argument that you first write down the “no-response” burden in order to arrive at the actual estimated burden, as the authors seem to note. That is not an argument for coming up with a “no adjustment” estimate and marketing it to The New York Times (and others?) as correct and based on normal assumptions, without first adjusting for incentives and capital responses and shifts in the ultimate tax burden. Would we have known about these underlying assumptions — which lie behind their subsequent calculation of wealth inequality — at all, if not for the tireless work of Phil Magness and Wojtek Kopczuk on Twitter?

Returning to the paper, it has some quite weak sentences, such as: “But it [no adjustment] also has the advantage of not being dependent on assumptions on behavioral responses.”

You might as well argue that assuming zero price elasticity of demand “has the advantage of not being dependent on assumptions on behavioral responses.” In reality, one is assuming about the least plausible behavioral response possible.

Here is some background material from Wojtek Kopczuk, which works through how the proffered inequality measures and corporate tax assumptions are related. And from Steven Hamilton. Here is also the recent David Splinter summary analysis on tax progressivity. Wojtek notes in his Twitter thread:

The bottom line: corporate tax should be felt by other forms of capital. That’s the standard assumption. CBO makes it, Auten-Splinter make it, Piketty-Saez-Zucman make it. Who does not? Saez-Zucman (2019) do not.

Here is the semantic innovation from the Saez-Zucman paper:

We think it is more useful to say that cutting corporate taxes could increase workers’ wages rather than say

that the tax burden on workers would fall.

Say both! Here are two well-known and also generally accepted AER papers suggesting that the corporate income tax places a burden on real wages.

Michael Smart agrees with me on the new Saez-Zucman piece:

Zucman has now kindly posted an early working paper to support the SZ assumption. I do not find this WP convincing. We’re simply told that the “natural description” of tax incidence is its legal incidence, i.e. 100% shareholder incidence of CIT.

I find this episode appalling, and I hope The New York Times is properly upset at having been “had.”

#TheGreatForgetting

Corporate income tax rates in Nash equilibrium

This is from the job market paper of Yang Shen, a candidate at Brown University:

I calibrate a three-country version of the model to data on trade, MP, and corporate tax rates for Germany, Ireland, and the United States. I then compute the Nash equilibrium corporate tax rates and calculate the associated welfare changes. The United States would undertake the largest tax cut in the Nash equilibrium, in an attempt to widen market entry of marginal firms. All three countries would experience welfare gains under the Nash tax rates.

In her model, the United States should cut its corporate tax rate by eleven percentage points. Shout it from the rooftops, as they say…

Should there be a tax on corporate income at all. For and against.

That is a reader request. I used to think the ideal tax rate on corporations should be zero, but that is no longer my view. For one thing, too many individuals would find ways to self-incorporate, thereby avoiding personal income taxes on labor income. Note that a small corporation controlled by you can return real income to you in a variety of non-taxable or less-taxed ways.

Furthermore, tax-exempt institutions such as non-profits and pension fund would end up owning too many corporations, to the detriment of (non-tax) efficiency. While pension funds eventually must pay out that income in the form of pensions, those often go to high-wealth, low income elderly individuals, and thus would never end up taxed at such a high rate.

I now think that for the United States the tax rate on corporate income should be in the range of 18-25 percent, depending of course on what other decisions we make with our budget and tax systems. It also would work to simply target the OECD average of the corporate rate.

A further question is whether the case for a zero corporate rate would be stronger if we shifted from income to consumption taxation. That depends how easy it might be to partially evade the consumption tax, say by spending money abroad. In general, to the extent evasion is possible that favors lower marginal tax rates but levied on a greater number of distinct points in the system, including in this case on the corporate veil.

I thank Megan McArdle for a useful conversation related to these points.

Should we abolish the corporate income tax and raise taxes on shareholders?

Mike Lee says yes, see also Matt. Maybe, I would like to go this route, but I’m not (yet?) convinced. What if non-profits and foreign companies end up as the shareholders, as indeed the Coase theorem would seem to indicate? Doesn’t that lower tax revenue because they wouldn’t be making capital gains filings? And to some extent, isn’t the U.S. tax system then encouraging inefficient ownership and governance?

There may be an answer to this worry, but I’ve yet to see it.

How might corporate income tax be changed?

This is what is circulating in the House, Trump and the Senate have yet to influence it directly:

KEY DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CURRENT U.S. CORPORATE TAXES AND HOUSE GOP PROPOSAL

Corporate Tax Rate:

Current: 35%

Proposal: 20%Capital Expenses:

Current: Depreciated over time

Proposal: Deducted immediatelyInterest Expenses:

Current: Deductible.

Proposal: Net interest expense not deductibleBasis for Location of Taxation:

Current: Profits

Proposal: SalesTaxation of Foreign Profits:

Current: Pay foreign tax, pay U.S. tax upon repatriation, minus foreign tax credits

Proposal: Generally repatriated without U.S. taxes, after one-time transition taxBorder Adjustments:

Current: None

Proposal: Tax applied to imports, removed from exports

There is more at the WSJ link, a very clear and useful piece by Richard Rubin. Do note that a stronger dollar — which we already see — will undo some of this effort to put American exports on a stronger footing. And deducting capital expenses immediately seems like an attempt to goose up the current economy in an unwise and unsustainable fashion. The lower corporate tax rate is a good idea. What are your opinions on these changes?

Only about one-quarter of corporate stock is owned by taxable shareholders

Only about one-quarter of U.S. corporate stock is held in taxable accounts, far less than most researchers and policymakers thought. The share has declined sharply from more than four-fifths in 1965. In a report published today in the journal Tax Notes, my Tax Policy Center colleague Lydia Austin and I found the other three-quarters of shares now are held in tax-exempt accounts such as IRAs or defined benefit/contribution plans, or by foreigners, nonprofits or others.

That is Steven M. Rosenthal, here is further information.

Should we still get rid of the U.S. corporate income tax?

I know this argument runs against the mood affiliation of our times, but the arguments for eliminating the corporate income tax still seem pretty good to me. Here is a recent paper by Hans Fehr, Sabine Jokisch, Ashwin Kambhampati, and Laurence J. Kotlikoff. The abstract runs as follows:

We simulate corporate tax reform in a single good, five-region (U.S., Europe, Japan, China, India) model, featuring skilled and unskilled labor, detailed region-specific demographics and fiscal policies. Eliminating the model’s U.S. corporate income tax produces rapid and dramatic increases in the model’s level of U.S. investment, output, and real wages, making the tax cut self-financing to a significant extent. Somewhat smaller gains arise from revenue-neutral base broadening, specifically cutting the corporate tax rate to 9 percent and eliminating tax loop-holes.

The NBER copy is here. An ungated copy you will find here (pdf).

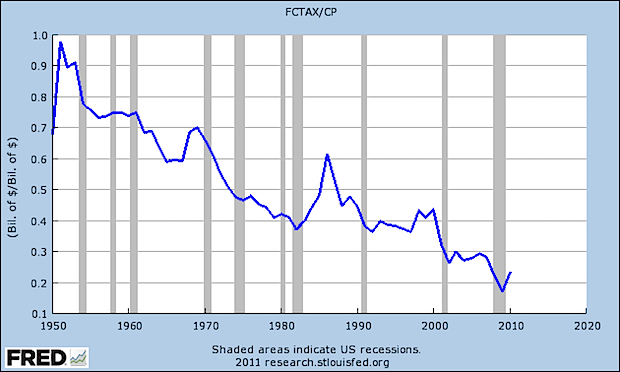

Corporate income tax as a share of corporate profits

That is from Felix Salmon, or try this one, namely corporate income tax as a percentage of gdp:

I still think the corporate rate should be zero, but the corporate income tax is one of the most commonly over-villainized institutions by the intelligent Right.

Addendum: Kevin Drum offers up a related chart.

Our corporate income tax

Cato tells it like it is:

The United States should be a leader but has fallen behind on tax reform. For example, the United States now has one of the highest corporate tax rates among major nations. The chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers, Glenn Hubbard, believes that “from an income tax perspective, the United States has become one of the least attractive industrial countries in which to locate the headquarters of a multinational corporation.” …

One-third of the sales of the 500 largest U.S. companies is now from their foreign affiliates. …

A new survey by the accounting firm KPMG, which takes into account both national and subnational taxes, found that the average 40 percent U.S. federal and state corporate rate combined is almost 9 percentage points higher than the OECD average in 2002 of 31.4 percent. …

In all there are six often-overlapping anti-deferral regimes that create a complex web for Americans to navigate through when investing abroad. The U.S. international tax rules are generally considered the most complex and aggressive among the industrial nations. In a 1999 report, the National Foreign Trade Council concluded that “U.S. anti-deferral rules have been subject to constant legislative tinkering, which has created both instability and a forbiddingly arcane web of rules, exceptions, exceptions to exceptions, interactions, cross references, and effective dates, giving rise to a level of complexity that is intolerable.” …

The complexity of tax rules on U.S. foreign income is so great that one estimate found that 46 percent of federal tax compliance costs for Fortune 500 companies stemmed from rules on foreign income. As a result, U.S. companies are at a tax disadvantage in world markets. … Intel’s vice president for taxes testified before Congress that, “if I had known at Intel’s founding what I know today about the international tax rules, I would have advised that the parent company be established outside of the U.S.”

Thanks to RegionsofMind for the link. My bottom line: I’d rather have cut the corporate income tax than have cut the tax on dividends.

Reforming the corporate income tax

Not as sexy a topic as cads and dads, see immediately below. But here is the best short article I have seen on why we should reform the corporate income tax.

Levi Strauss was able to put about $100,000 into a sham Brazilian venture that netted it $180 million in tax deductions. And it was all perfectly legal.

The answer?:

Loopholes need to be closed, rules simplified and the 35 percent rate reduced. And serious thought has to be given to augmenting the corporate tax with an export-friendly value-added tax like the ones used by nearly every other industrial country.

I agree with the first sentence of that paragraph, but not the second. I worry about the transition costs to a VAT, I expect we would end up with both a VAT and an income tax and on that one I vote no.

The California tax burden is driving people out

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit:

California’s highest income tax rate is 13.3%. That is in addition to a top federal tax rate of 37%. California also has a state sales tax rate of 7.25%, and many localities impose a smaller sales tax. So if a wealthy person earns and spends labor income in the state of California, the tax rate at the margin could approach 60%. Then there is the corporate state income tax rate of 8.84%, some of which is passed along to consumers through higher prices. That increases the tax burden further yet.

And this:

Researchers Joshua Rauh and Ryan Shyu, currently and formerly at Stanford business school, have studied the behavioral response to Proposition 30, which boosted California’s marginal tax rates by up to 3% for high earners for seven years, from 2012 to 2018. They found that in 2013, an additional 0.8% of the top bracket of the residential tax base left the state. That is several times higher than the tax responses usually seen in the data.

These high-earning California residents seem to have reached a tipping point: Maybe many of them could afford the extra tax burden, but at some point they got fed up, read the signals and decided the broader system wasn’t working in their interest.

Overall, Proposition 30 increased total tax revenue for California — but not nearly as much as intended. Due to departures, the state lost more than 45% of its windfall tax revenues from the policy change, and within two years the state lost more than 60% of those same revenues.

Do tax increases tame inflation?

Here is a new AER article by James Cloyne, Joseba Martinez, Haroon Mumtax, and Paolo Surico. After an extensive data analysis, they arrive at this conclusion:

Based on US federal tax changes post–World War II, our answer is “yes” if personal income taxes are increased but “no” if corporate income taxes are increased.

Of course this is consistent with the view — no longer so commonly admitted — that higher corporate tax rates do have negative supply side effects. There is an ungated version of the paper here.