Results for “hft” 42 found

Tick Size and Listings

In earlier posts I have argued for a smaller tick size to reduce rent-seeking. The Wall Street Journal reports today that there is a move to increase tick size in order to increase rent seeking.

Smaller and lesser-known companies could benefit from being nickel-and-dimed, at least on stock markets.

Allowing thinly traded stocks to rise or fall in broader increments–five or ten cents versus the current penny, for instance–could help those securities draw more investors and make their shares easier to trade, according to exchange and brokerage executives.

Publicly traded companies or those eyeing an initial public offering should have the ability to choose whether they want their shares to move cent-by-cent or in larger steps, executives told lawmakers at a Wednesday hearing in Washington.

In other cases, exchanges ought to be able to transact the most heavily traded shares in fractions of a cent, some said.

There is a case for having a tick-size function, in which tick sizes would change with share price and perhaps also volume. Many exchanges in the world have such tick functions. I am suspicious, however, when industry insiders plump for higher tick sizes as being in the public interest. In particular, I have doubts that this is true:

Wall Street’s current methods for trading stocks have helped fuel a slide in the number of publicly traded companies, according to David Weild, senior adviser with Grant Thornton LLP. He told lawmakers Wednesday that the number of U.S.-listed companies has declined steadily for the last 15 years, with an average 208 listings falling off exchanges per year since 2002.

The increments by which stocks can be bought or sold, known as their “tick size,” are a key factor, Weild said at the hearing. Trimming the increment to one cent created more potential prices at which shares can trade, making it more work for traders to ensure liquidity, he said.

IPOs and listings are down but I think tick size is at most a minor reason. There are more plausible reasons for declining listings including more competition from abroad, greater use of private equity, increased stringency of regulation in the United States (SOX) and perhaps also declining profitability of small firms.

FYI, here is the testimony from the hearing before the House Financial Services Committee.

Hat tip: John Welborn.

The Volume Clock

That is the title of a new paper by David Easley, Marcos M. Lopez de Prado, and Maureen O’Hara:

Abstract:

Over the last two centuries, technological advantages have allowed some traders to be faster than others. We argue that, contrary to popular perception, speed is not the defining characteristic that sets High Frequency Trading (HFT) apart. HFT is the natural evolution of a new trading paradigm that is characterized by strategic decisions made in a volume-clock metric. Even if the speed advantage disappears, HFT will evolve to continue exploiting Low Frequency Trading’s (LFT) structural weaknesses. However, LFT practitioners are not defenseless against HFT players, and we offer options that can help them survive and adapt to this new environment.

The paper has many interesting bits, such as this:

Databases with trillions of observations are now commonplace in financial firms. Machine learning methods, such as Nearest Neighbor or Multivariate Embedding algorithms search for patterns within a library of recorded events. This ability to process and learn from what is known as “big data” only reinforces the advantages of HFT’s “event-time” paradigm, very much like how “Deep Blue” could assign probabilities to Kasparov’s next 20 moves, based on hundreds of thousands of past games (or more recently, why Watson could outplay his Jeopardy opponents).

The upshot is that speed makes HFTs more effective, but slowing them down won’t change their basic behavior: Strategic sequential trading in event time.

One message of the paper is that sequential strategic behavior will occur at any speed. I liked this sentence:

As we have seen, HFT algos can easily detect when there is a human in the trading room, and take advantage.

And the ending bit is this:

There is a natural balance between HFTs and LFTs. Just as in nature the number of predators is limited by the available prey, the number of HFTs is constrained by the available LFT flows. Rather than seeking “endangered species” status for LFTs (by virtue of legislative action like a Tobin tax or speed limit), it seems more efficient and less intrusive to starve some HFTs by making LFTs smarter. Carrier pigeons or dedicated fiber optic cable notwithstanding, the market still operates to provide liquidity and price discovery – only now it does it very quickly and strategically.

Should Stocks Trade in Increments of $.0001?

In Modern Principles Tyler and I explain that price floors create wasteful increases in quality. The classic story is the Civil Aeronautics Board’s regulation of airline prices between 1938 and 1978. Through entry, exit and price regulation, the CAB kept prices above market levels and airlines earned excess profits with every customer. Although the airlines were not allowed to compete on price they could compete to attract customers by offering better meals, wider seats and more frequent flights. Airline quality, as a result, was high but it was inefficiently high; for example, too many flights flew half empty. More fundamentally, if airlines compete by lowering prices by $100, customers are automatically better off by $100. But when airlines have no choice but to compete by spending $100 on “quality” customers are not necessarily better off by $100. Indeed, enforced non-price competition will always result in more spending than value creation on the margin. If given the choice, customers would have preferred lower prices to higher quality but until deregulation in 1978 they were not given the choice. Thus, price floors create wasteful increases in quality.

Ok, so where does stock pricing come into play? Chris Stucchio, a high-frequency trader, argues that the sub-penny rule, SEC Rule 612, “essentially acts as a price floor on liquidity – it is illegal to sell liquidity at a price lower than $0.01.” As a result, traders compete on speed (latency) rather than on price.

As with a classical minimum wage, two parties are harmed – the purchaser (who must pay extra) and the lower priced seller (who is pushed out of the market).

Similarly, at prices higher than $0.01, it makes price movements lumpy – on a bid ask spread of $0.05, it is illegal for someone to enter the market at price $0.049 or $0.045. Thus, at any price point, speculators are forced to compete on latency rather than on price. Price competition is only possible if one market maker is willing to offer a price at least $0.01 better than another, which is often not the case.

When price competition is impossible, market makers must compete for business via other methods – in this case latency.

As with the airlines, the increase in speed–now such that 40,000 trades can be executed in the literal blink of an eye and relativity matters–is profitable for the traders even though it doesn’t add nearly as much to customer or social welfare. As I wrote earlier:

A small increase in speed over one’s rivals has a large effect on who wins the race but no effect on whether the race is won and only a small effect on how quickly the race is won. We get too much investment in innovations with big influences on distribution and small (or even negative) improvements in efficiency and not enough investment in innovations that improve efficiency without much influencing distribution (i.e. innovations in goods with big positive externalities).

Penny pricing (and before that 1/16th pricing) made sense when stocks were mostly traded by humans and we needed to conserve cognition but, as Stucchio points out, most trading today is done by computers and pricing in hundredths of a penny (or less) would not impose any extra effort on the computers. Pricing in 1/100ths of a penny, however, would dramatically increase price competition and reduce wasteful quality competition.

Here are previous MR posts on HFT about which Tyler and I have debated.

Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit

The skills necessary to ride a bike are multifaceted, complex and not at all obvious or even easily explicable to the conscious mind. Once you learn, however, you never forget–that is the power of habit. Without the power of habit, we would be lost. Once a routine is programmed into system one (to use Kahneman’s terminology) we can accomplish great skills with astonishing ease. Our conscious mind, our system two, is not nearly fast enough or accurate enough to handle even what seems like a relatively simple task such as hitting a golf ball–which is why sports stars must learn to turn off system two, to practice “the art of not thinking,” in order to succeed.

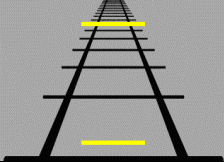

Habits, however, can easily lead one into error. In the picture at right, which yellow line is longer? System one tells us that the l ine at the top is longer even though we all know that the lines are the same size. Measure once, measure twice, measure again and again and still the one at top looks longer at first glance. Now consider that this task is simple and system two knows with great certainty and conviction that the lines are the same and yet even so, it takes effort to overcome system one. Is it any wonder that we have much greater difficulty overcoming system one when the task is more complicated and system two less certain?

ine at the top is longer even though we all know that the lines are the same size. Measure once, measure twice, measure again and again and still the one at top looks longer at first glance. Now consider that this task is simple and system two knows with great certainty and conviction that the lines are the same and yet even so, it takes effort to overcome system one. Is it any wonder that we have much greater difficulty overcoming system one when the task is more complicated and system two less certain?

You never forget how to ride a bike. You also never forget how to eat, drink, or gamble–that is, you never forget the cues and rewards that boot up your behavioral routine, the habit loop. The habit loop is great when we need to reverse out of the driveway in the morning; cue the routine and let the zombie-within take over–we don’t even have to think about it–and we are out of the driveway in a flash. It’s not so great when we don’t want to eat the cookie on the counter–the cookie is seen, the routine is cued and the zombie-within gobbles it up–we don’t even have to think about it–oh sure, sometimes system two protests but heh what’s one cookie? And who is to say, maybe the line at the top is longer, it sure looks that way. Yum.

System two is at a distinct disadvantage and never more so when system one is backed by billions of dollars in advertising and research designed to encourage system one and armor it against the competition, skeptical system two. Yes, a company can make money selling rope to system two, but system one is the big spender.

Habits can never truly be broken but if one can recognize the cues and substitute different rewards to produce new routines, bad habits can be replaced with other, hopefully better habits. It’s habits all the way down but we have some choice about which habits bear the ego.

Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit, about which I am riffing off here, is all about habits and how they play out in the lives of people, organizations and cultures. I most enjoyed the opening and closing sections on the psychology of habits which can be read as a kind of user’s manual for managing your system one. The Power of Habit, following the Gladwellian style, also includes sections on the habits of corporations and groups (hello lucrative speaking gigs) some of these lost the main theme for me but the stories about Alcoa, Starbucks and the Civil Rights movement were still very good.

Duhigg is an excellent writer (he is the co-author of the recent investigative article on Apple, manufacturing and China that received so much attention) It will also not have escaped the reader’s attention that if a book about habits isn’t a great read then the author doesn’t know his material. Duhigg knows his material. The Power of Habit was hard to put down.

The Innovation Nation versus the Warfare-Welfare State

We like to think of ourselves as an innovation nation but our government is a warfare-welfare state. To build an economy for the 21st century we need to increase the rate of innovation and to do that we need to put innovation at the center of our national vision. Innovation, however, is not a priority of our massive federal government.

Nearly two-thirds of the U.S. federal budget, $2.2 trillion annually, is spent on just the four biggest warfare and welfare programs, Medicaid, Medicare, Defense and Social Security. In contrast the National Institutes of Health, which funds medical research, spends $31 billion annually, and the National Science Foundation spends just $7 billion.

That’s me writing at The Atlantic drawing on Launching the Innovation Renaissance. Here is one more bit:

Our ancestors were bold and industrious–they built a significant portion of our energy and road infrastructure more than half a century ago. It would be almost impossible to build that system today. Could we build the Hoover Dam today? We have the technology but do we have the will? Unfortunately, we cannot rely on the infrastructure of our past to travel to our future. Airports, an electricity smart grid that doesn’t throw millions into the dark every few years, ubiquitous Wi-Fi — these are among the important infrastructures of the 21st century, and they are caught in the regulatory thicket.

Putting innovation at the center of the national vision is not simply about spending more, it’s about how we approach all problems. Read the whole thing for more discussion of regulation and other issues.

Terrence Hendershott writes to me

Below are thoughts from an author of a paper Tyler cited on algorithmic trading (and HFT). There is a project by the UK government on related topics. Some related working papers on HFT are here, here, here, here, and here.

1. Technology has made financial markets work better; improvements in liquidity are large, important, and should result in lower costs of capital for firms; these do not mean that every application of technology is good.

2. There is evidence that investors prefer continuous to periodic trading, but batch auctions as frequent as every few seconds have not been studied.

3. Until technology allows buyers and sellers to better find each other simultaneously, markets need a group of intermediaries; the lowest-cost intermediaries are those closest to the market.

4. Historically, intermediaries were floor traders, now are HFT; floor traders profit from those further from the trading mechanism as do HFT now.

5. What is the best industrial organization for the intermediation sector? i) free entry (HFT) or ii) regulated oligopoly (NYSE specialists, Nasdaq market makers, etc.)?

6. Floor trading had the advantage that within-market relative latency was not so important and the amount of market data produced was small; costs were floor traders’ large advantages and possible collusion.

7. There is yet to be robust empirical evidence linking HFT to declines in market quality or efficiency; Haldane has interesting ideas, but as comments point out, it is difficult to blame HFT more than the economic and euro crises for recent fat tails in asset returns; systemic uncertainty increases fat tails and cross-asset correlations.

Overall, technology applied to intermediation appears to bring benefits with the standard rent seeking costs of intermediaries making money, possible instability (although 1987 showed human markets have their own failings), and technology costs.

Can markets find solutions?

i) If HFT becomes competitive (zero rents), will HFT then resell their technology as brokers? Could this lead to efficiency without negative externalities?

ii) Do dark pools and batch auctions limit part of the “arms race” of technology investment? Significant volumes are already traded in these ways, e.g., the opening and closing auctions. There are many ways investors can avoid HFT. If they do not, is it revealed preference?

If regulations are needed they should target behavior, not certain trading firms, otherwise HFT features will simply be incorporated into other strategies, e.g., a HFT strategy is merged with a mid-frequency strategy.

More on High Frequency Trading and Liquidity

Tyler is more optimistic about financial innovation than I am. Strange, but true. I recommend Andrew Haldane’s speech, The Race to Zero, on high frequency trading (HFT). Haldane is Executive Director for Financial Stability at the Bank of England and his speech is eminently quotable. First, some background from Haldane:

- As recently as 2005, HFT accounted for less than a fifth of US equity market turnover by volume. Today, it accounts for between two-thirds and three-quarters.

- HFT algorithms have to be highly adaptive, not least to keep pace with the evolution of new algorithms. The half-life of an HFT algorithm can often be measured in weeks.

- As recently as a few years ago, trade execution times reached “blink speed” – as fast as the blink of an eye….As of today, the lower limit for trade execution appears to be around 10 micro-seconds. This means it would in principle be possible to execute around 40,000 back-to-back trades in the blink of an eye. If supermarkets ran HFT programmes, the average household could complete its shopping for a lifetime in under a second.

- HFT has had three key effects on markets. First, it has meant ever-larger volumes of trading have been compressed into ever-smaller chunks of time. Second, it has meant strategic behaviour among traders is occurring at ever-higher frequencies. Third, it is not just that the speed of strategic interaction has changed but also its nature. Yesterday, interaction was human-to-human. Today, it is machine-to-machine, algorithm-to-algorithm. For algorithms with the lifespan of a ladybird, this makes for rapid evolutionary adaptation.

Consistent with the research cited by Tyler, Haldane notes that bid-ask spreads have fallen dramatically.

Bid-ask spreads have fallen by an order of magnitude since 2004, from around 0.023 to 0.002 percentage points. On this metric, market liquidity and efficiency appear to have improved. HFT has greased the wheels of modern finance.

But at the same time that bid-ask spread have decreased on average, volatility has sharply increased, as illustrated most clearly with the flash crash

Taken together, this evidence suggests something important. Far from solving the liquidity problem in situations of stress, HFT firms appear to have added to it. And far from mitigating market stress, HFT appears to have amplified it. HFT liquidity, evident in sharply lower peacetime bid-ask spreads, may be illusory. In wartime, it disappears.

In particular, what has happened is that stock prices have become less normal (Gaussian), more fat-tailed, over shorter periods of time.

Cramming ever-larger volumes of strategic, adaptive trading into ever-smaller time intervals would, following Mandelbrot, tend to increase abnormalities in prices when measured in clock time. It will make for fatter, more persistent tails at ever-higher frequencies. That is what we appear, increasingly, to find in financial market prices in practice, whether in volatility and correlation or in fat tails and persistence.

HFT strategies work across markets (e.g. derivatives), exchanges, and stocks and can have negative externality effects on low frequency traders. As a result, micro fat-tails can become macro fat-tails.

Taken together, these contagion channels suggest that fat-tailed persistence in individual stocks could quickly be magnified to wider classes of asset, exchange and market. The micro would transmute to the macro. This is very much in the spirit of Mandelbrot’s fractal story. Structures exhibiting self-similarity magnify micro behaviour to the macro level. Micro-level abnormalities manifest as system-wide instabilities.

For these reasons I am not enthusiastic about innovations in HFT. Earlier I compared high-tech swimming suits and high-frequency trading:

High-tech swimming suits and trading systems are primarily about distribution not efficiency. A small increase in speed over one’s rivals has a large effect on who wins the race but no effect on whether the race is won and only a small effect on how quickly the race is won. We get too much investment in innovations with big influences on distribution and small, or even negative, improvements in efficiency and not enough investment in innovations that improve efficiency without much influencing distribution, i.e. innovations in goods with big positive externalities.

Would temporary capital controls for Greece work?

Has anyone written a good blog post about this topic?

If you allow redemption of accounts into currency, the currency can be mailed, carried across borders, sent by PayPal against credit cards, sent by Western Union, or many other options. It would be hard to shut them all down at once. The Greek government could try. Carrying currency across the border would be the hardest one to stop, although it might not be the most important external channel for getting funds out of the country. They could search people at the border, much as the U.S. government now searches us for liquids before a plane flight.

A second scenario freezes bank accounts and doesn’t worry too much about currency leakage. Instead it stops people from adding to their currency holdings, or at least tries to. The Greek economy then has to do without currency withdrawals for some time, until the new drachma currency is ready.

Which is the more feasible option? Is either at all an option? Am I overlooking an alternative? Without some kind of capital controls, a move away from the euro simply drains the country of its euros.

Do our intuitions about deadweight loss break down at very small scales?

I’ve been thinking about high-frequency trading again. Some of the issues surrounding HFT may come from whether our intuitions break down at very small scales.

Take the ordinary arbitrage of bananas. If one banana sells for $1 and another for $2, no one worries that the arbitrageurs, who push the two prices together, are wasting social resources. We need the right price signal in place and the elimination of deadweight loss is not in general “too small” to be happy about.

But at tiny enough scales, we stop being able to see why the correct price is the “better” price, from a social point of view. Think of the marginal HFT act as bringing the correct price a millisecond earlier, so quickly that no human outside the process notices, much less changes an investment decision on the basis of the better price coming more quickly. (Will we ever use equally fast computers to make non-financial, real investment decisions in equally small shreds of time? Would that boost the case for HFT? Is HFT “too early to the party”? If so, does it get credit for starting the party and eventually accelerating the reactions on the real investment side?)

HFT also lowers liquidity risk in many cases (it is easier to resell a holding, especially for long-term investors, as day churners can get caught in the froth), and thereby improving the steady-state market price, again especially for long-term investors. That too could improve investment decisions, even if the improvement in the price is small in absolute terms.

Some decisions based on prices have to rely on very particular thresholds. If no tiny price change stands a chance of triggering that threshold, we encounter the absurdity of there being no threshold at all. We fall into the paradoxes of the intransitivity of indifference and you end up with too many small grains of sugar in your coffee.

So maybe a tiny price improvement, across a very small area of the price space, carries a small chance of prompting a very large corrective adjustment, with a comparably large social gain. Yet we never know when we are seeing the adjustment. The smaller the scale of the price improvement, the less frequently the real economy gains come, but in expected value terms those gains remain large relative to the resources used for arbitrage, just as in the bananas case. It’s not obvious why operating on a smaller scale of price changes should change this familiar logic. Is the key difference of smaller scales, combined with lumpy real economy adjustments, a greater infrequency of benefit but intact expected gains?

In this model the HFTers labor, perhaps blind to their own virtues, and bring one big grand social benefit, invisibly, every now and then. Occasionally, for real investors, their trades help the market cross a threshold which matters.

I am reminded of vegetarians. Say you stop eating chickens. You are small relative to the market. Does your behavior ever prompt the supermarket to order a smaller number of chickens based on a changed inventory count? Or are all the small rebellions simply lost in a broader froth?

What is the mean expected time that HFT must run before it triggers a threshold significant for the real economy?

Aren’t the rent-seeking costs of HFT near zero? Long-term investors do not have to buy and sell into the possible froth. HFTers thus “tax” the traders who were previously the quickest to respond, discourage their trading, and push the rent-seeking costs of those traders out of the picture. More fast computers, fewer carrier pigeons. Are there models in which total rent-seeking costs can fall, as a result of HFT? Does it depend on whether fast computers or pigeons are more subject to production economies of scale?

Brasilia notes

Could this be the strangest city I have visited? And yet the people, the mood, the food, and the culture all seem quite normal, whatever that means.

I had not realized how much the city center was patterned after the Washington Mall, yet with modernist rather than classical buildings for the government, and with a modernist layout. On each side of the major highway is “Crystal City on steroids,” with five-lane highways, boxy skyscrapers, and a huge bus station straddling the main road. It resembles an old science fiction movie and yes I like old science fiction movies. View here, and it really looks like this! It is no wonder that the aliens chose Brazil to visit.

There is also a private sector presence here. Don’t forget the neat bridge. Here is my favorite church in town, Dom Bosco. Here is the fine Palacio Itamarati.

The Memorial JK is an egotistical political monument. It was built by Niemeyer in 1980 to honor the founder of Brasilia, Juscelino Kubitschek, former President of Brazil, which is in turn a way to honor Niemayer. Kubitschek’s remains lie beneath a skylight in a granite tomb, and the coffin reads O FUNDADOR. The surrounding rooms are full of insufferable photos, suits, medals, and tie clips.

The clouds and skies are first-rate.

The home of the vice President is surrounded by ostriches.

A new paper on high-frequency trading

The author is Jonathan Brogaard of Northwestern and here is the abstract:

This paper examines the impact of high frequency traders (HFTs) on equities markets. I analyze a unique data set to study the strategies utilized by HFTs, their profitability, and their relationship with characteristics of the overall market, including liquidity, price efficiency, and volatility. I find that in my sample HFTs participate in 77% of all trades and that they tend to engage in a price-reversal strategy. I find no evidence suggesting HFTs withdraw from markets in bad times or that they engage in abnormal front-running of large non-HFTs trades. The 26 high frequency trading (HFT) firms in the sample earn approximately $3 billion in profits annually. HFTs demand liquidity for 50.4% of all trades and supply liquidity for 51.4% of all trades. HFTs tend to demand liquidity in smaller amounts, and trades before and after a HFT demanded trade occur more quickly than other trades. HFTs provide the inside quotes approximately 50% of the time. In addition if HFTs were not part of the market, the average trade of 100 shares would result in a price movement of $.013 more than it currently does, while a trade of 1000 shares would cause the price to move an additional $.056. HFTs are an integral part of the price discovery process and price efficiency. Utilizing a variety of measures introduced by Hasbrouck (1991a, 1991b, 1995), I show that HFTs trades and quotes contribute more to price discovery than do non-HFTs activity. Finally, HFT reduces volatility. By constructing a hypothetical alternative price path that removes HFTs from the market, I show that the volatility of stocks is roughly unchanged when HFT initiated trades are eliminated and significantly higher when all types of HFT trades are removed.

The paper you can find here, and I thank a loyal MR reader for the pointer.

Further points on high-frequency trading

Here is a good survey of some of the debates, plus Paul Krugman mentions the topic in his column today. Here's my earlier post but I'd like to add or reiterate a few points:

1. On one hand, critics wish to charge that there is little or no advantage to having prices move more quickly to reflect new information. On the other hand, some of these same critics charge that short-run volatility of prices — assuming this is in fact the result of HFT (and that is not proven) — creates social costs. That's not quite a contradiction but it is an odd mix of views about the relevance of the short run.

2. I haven't seen a good estimate, or for that matter a bad estimate, of the social loss involved from investing resources in HFT. Even if the practice has no gain, I suspect the loss is small. It's the symbolic nature of the issue which excites people — bailed-out elites doing fancy things with powerful computers in a non-egalitarian manner — rather than the belief that it is a policy priority. Even if you think HFT is bad, on an actual list of bad policies or practices in our world, would it be in the top million? Mostly it's a canvas on which to paint complaints about the continuing political and economic power of finance, but we shouldn't let that skew our judgment of the practice itself.

3. There is no argument to date, and probably no argument period, that HFT can lead to financial insolvency or collapse on a major scale. The cost, if there is one, is that the associated trading strategies bring a temporary collapse of asset prices for some period of time (how long?) or perhaps greater ongoing price volatility, or uncertainty about order execution, in the short run.

When I read that HFT may give markets "a new, currently unknown set of emergent properties" I think buying opportunity.

4. Research by Hans Stoll indicated that program trading was not in fact an instrumental culprit behind Black Monday in 1987, yet media coverage of HFT seems to be indicating that it was. Many of the HFT debates echo themes from the earlier program trading debates from the late 1980s but in fact program trading did not turn out to be a major problem. We have been down this path before and it turned out there was much less there than the critics thought at the time.

5. The more I read these debates, the more nervous I get about the idea of a financial products safety commission. Essentially on innovation we're seeing a flipping of the burden of proof and I don't think it is possible to easily fine-tune that flipping in a way to capture good innovations and rule out bad ones. We should still follow the rule of regulating practices shown to be harmful or likely to be harmful.