Results for “the tipping point” 48 found

The tipping point

Suppose that of the N member-states, F (e.g. 3, as is the case at the moment of writing) have ‘fallen’ out of the money markets and into the EFSF’s bosom. The EFSF must then finance their debts entirely until the Crisis ends. To do so it must seek loan guarantees from the N-F still solvent member-states. It is extremely easy to show that the contribution (as a portion of their GDP) of the N-F solvent member-states to the ‘fallen’ member-states, let’s call it αF (where the subscript indicates the number of ‘fallen’ states that must be supported) equals some newfangled debt-to-GDP ratio: The numerator is the total debt of the ‘fallen’ and the denominator is the total GDP of the still solvent member-states. (See here for a brief proof.) The reason I choose to call αF a toxic ratio is that, with every member-state that ‘falls’, this ratio rises even if GDP and debts remain the same. Moreover, every new casualty boosts the toxic ratio αF and guarantees that yet another member-state will join the rank of the ‘fallen’. And as if this were not enough, nothing can stop this process while everything else remains the same. Including the potential size of the EFSF.

Here is more. Thus enter the ECB and its bond-buying. Do Italy and Spain now count as belonging to “the fallen”? Or have they just returned from “the fallen”? Or maybe a bit of both?

Do “influentials” drive The Tipping Point?

In the past few years, Watts–a network-theory scientist who recently

took a sabbatical from Columbia University and is now working for Yahoo

(NASDAQ:YHOO) –has performed a series of controversial, barn-burning

experiments challenging the whole Influentials thesis. He has analyzed

email patterns and found that highly connected people are not, in fact,

crucial social hubs. He has written computer models of rumor spreading

and found that your average slob is just as likely as a well-connected

person to start a huge new trend. And last year, Watts demonstrated

that even the breakout success of a hot new pop band might be nearly

random. Any attempt to engineer success through Influentials, he

argues, is almost certainly doomed to failure.

Here is the full article. Here is the home page of Duncan Watts. Thanks to John DePalma for the pointer.

The Electric Vehicle Tipping Point?

Geoff Ralston, a partner at Y Combinator, argues that electric cars will soon dominate the world. He gives several arguments regarding cost and convenience that I take no issue with but his most interesting argument strikes me as wrong:

Gas stations are not massively profitable businesses. When 10% of the vehicles on the road are electric many of them will go out of business. This will immediately make driving a gasoline powered car more inconvenient. When that happens even more gasoline car owners will be convinced to switch and so on. Rapidly a tipping point will be reached, at which point finding a convenient gas station will be nearly impossible and owning a gasoline powered car will positively suck. Then, there will be a rush to electric cars….

Why is this wrong? Consider that in 2009 there were 246 million motor vehicles registered in the United States. A 10% reduction would be 221 million vehicles but that is how many vehicles there were in 2000. Was driving an automobile so much more inconvenient in 2000 than it was in 2009? No. Even a 25% fall in gas vehicles would bring us back only to the number of vehicles circa 1998.

More fundamentally, the argument goes wrong by not thinking through the incentives. Suppose that gasoline stations did become so uncommon that finding one was inconvenient. What will happen? More gasoline stations will be built! Ralston has implicitly assumed that building gasoline stations will add so much to the price of gasoline as to render that option uneconomic. In fact, gasoline stations are relatively simple, small businesses that easily expand or contract in response to the pennies on a gallon that people are willing to pay for convenience.

Addendum: By the way, even though the number of vehicles in the United States has been increasing, the number of gasoline stations has actually been decreasing, largely because greater fuel efficiency means that we want fewer stations.

Hat tip: Vlad Tarko.

The Point of Tipping?

Yesterday, my newspaper was delivered with a stamped envelope for sending tips to the delivery person. I put a tip in the envelope. Feeling extra generous, I did not include my address. Explain. Shouldn’t all tips be this way? Discuss.

The Online Tipping Outrage

The latest outrage cycle was started by April Glaser in Slate who is outraged that some online delivery companies apply tips to a worker’s base pay:

My first DoorDash order is probably my last because, as journalist Louise Matsakis put it on Twitter, “I don’t believe that a single person intends to give a tip to a multibillion dollar venture-backed startup. They are trying to tip the person who delivered their order.”

You will probably not be surprised, however, that Slate is also outraged at tipping.

Tipping is a repugnant custom. It’s bad for consumers and terrible for workers. It perpetuates racism.

But one way for a firm to get rid of tipping is to guarantee a payment per delivery. Many delivery workers may prefer such a system because tips are often perfunctory and therefore from the point of view of the worker random or they vary based on factors over which the delivery person has little control (e.g. worker race but also the customer’s online experience and whether other workers got the pizza into the oven on time). In other words, the no-tip system reduces the variance of pay. Moreover, it won’t reduce pay on average. Delivery workers will earn what similarly skilled workers earn elsewhere in the economy whether they get to keep “their” tips or not. The outrage over who gets the tip is similar to complaining about who pays the tax, the supplier or the demander.

There are exceptions. In some industries, such as bartending, the quality of the service can vary dramatically by worker and tips help to reward that extra quality when it is difficult to observe by the firm. In these industries, however, both the workers, at least the high quality workers, and the firms want tips. If the firms themselves are removing tips that is a sign that they think that the worker has little control over quality and thus tips serve no purpose other than to more or less randomly reward workers. Since random pay is less valuable than certain pay and firms are less risk averse than workers it makes sense for the firm to take on the risk of tips and instead pay a higher base (again, with the net being in line with what similar workers earn elsewhere).

In short, a job is a package of work characteristics and benefits and it’s better to let firms and workers choose those characteristics and benefits to reach efficient solutions than it is to try to move one characteristic on the incorrect assumption that all other characteristics will then remain the same, to do so is the happy meal fallacy in another guise.

The Uber Tipping Equilibrium

What is the effect of tipping on the take-home pay of Uber drivers? Economic theory offers a clear answer. Tipping has no effect on take home pay. The supply of Uber driver-hours is very elastic. Drivers can easily work more hours when the payment per ride increases and since every person with a decent car is a potential Uber driver it’s also easy for the number of drivers to expand when payments increase. As a good approximation, we can think of the supply of driver-hours as being perfectly elastic at a fixed market wage. What this means is that take home pay must stay constant even when tipping increases.

But how is the equilibrium maintained? One possibility is that as riders tip more, Uber can reduce fares so that the net hourly wage remains constant. Since take home pay doesn’t change we will have just as many drivers as before tipping. Under the tipping equilibrium the only change will be that instead of the riders paying Uber and then Uber paying the drivers, the riders will also pay something to the drivers directly and Uber will pay the drivers a little bit less. The drivers end up with the same take home pay.

But suppose that Uber doesn’t want to reduce fares or is somehow constrained from doing so. Does the model break down? Sorry, but the laws and supply and demand cannot be so easily ignored. If Uber holds fares constant, the higher net wage (tips plus fares) will attract more drivers but as the number of drivers increases their probability of finding a rider will fall. The drivers will earn more when driving but spend less time driving and more time idling. In other words, tipping will increase the “driving wage,” but reduce paid driving-time until the net hourly wage is pushed back down to the market wage.

At this point many readers will object that I am a horrible person and this is all theory using unrealistic “Econ 101” assumptions of perfectly competitive markets, rationality, full information etc etc. To which my response is that the first claim is plausible but irrelevant while the second is false. A new paper, Labor Market Equilibration: Evidence from Uber, from John Horton at NYU-Stern and Jonathan Hall and Daniel Knoepfle, two economists at Uber, looks at what happens when Uber increases base fares:

We find that when Uber raises the base fare

in a city, the driver hourly earnings rate rises immediately, but then begins

to decline shortly thereafter. After about 8 weeks, there is no detectable

difference in the average hourly earnings rate compared to before the fare

increase. With a higher fare, drivers earn more when driving passengers, and

so how do drivers make the same amount per hour? The main reason is that

driver utilization falls; drivers spend a smaller fraction of their working hours

on trips with paying passengers when fares are higher.

My conclusion is that increases in Uber fares are a very bad idea. Why? Increases in Uber fares–i.e. increases beyond those required to have enough drivers so that pick-up times are reasonably short–have two negative effects. First, and most obviously, higher fares increase the price to riders. Second, higher fares don’t result in higher driver earnings but do result in drivers wasting time.

The situation is very similar to the inefficient market for realtors. When realtors earn a fixed percentage of a home’s sales price, higher home prices encourage more entry into the realtor market. But we don’t need more realtors just because home prices have increased! When home prices are high, a realtor can earn enough selling a handful of homes a year to make it worthwhile to stay in the industry even though most of the realtor’s time is spent unproductively finding customers rather than actually helping customers to buy and sell homes. It would be better if commission rates fell when home prices rose but even after many years of online entry that typically doesn’t happen which is the mystery of realtor rent-seeking.

Uber is a great service for riders and it’s also great for people who need a source of flexible earnings. The fact that Uber drivers earn less than some people think is appropriate is a function of the wider job market and not of Uber policy. Indeed, Uber can’t increase take-home pay by raising fares and if we require them to do so we will simply hurt consumers and waste resources without improving the welfare of drivers.

Are we moving away from tipping?

A top New York restaurant is replacing tipping with a mandatory twenty percent service charge. In many other areas, such as hotels, tipping is declining as well.

Most economic analyses of tipping ask why so many customers will give up money for no apparent return. Put this puzzle aside, and ask why an establishment might move to the fixed charge.

Ralph Frasca explains the legal difference between a tip and a service charge. The employer may legally keep the service charge but not the tip. This suggests at least three hypotheses:

1. A restaurant is using the new service charge to raise prices. One of the new service charges is set at 20 percent, which is more than most people tip. (Do note: this one particular New York restaurant claims they wish to redress the distribution of tip money in favor of the kitchen and away from serving staff. Furthermore the restaurant is fancy, and some customers do tip 20 percent or more there.)

2. The balance of power in labor markets is shifting against workers. We therefore see owners trying to capture tipping income. Some of this income will be given back in the form of higher wages, but some of it will be kept by owners. Perhaps this is the most palatable way of rewriting the implicit labor-management contract.

3. Employers can monitor waiter/waitress quality better than before. So why leave compensation in the hands of the customers? Under this hypothesis, employers are not looking to capture tipping income, rather they seek to control it by their own standards.

Here is James Surowiecki on tipping. Here is a New York Times article on tipping. Here is my previous post on tipping. Comments are on, and thanks to Stephen Bainbridge for a pointer and suggestion.

Addendum: One ranting waiter notes: "Experience has shown that customers use verbal praise to supplement a poor monetary reward."

A short history of economics at U. Mass Amherst

From Dylan Matthews. Here is an excerpt:

The tipping point, Wolff says, was the denial of tenure for Michael Best, a popular, left-leaning junior professor. “He had a lot of student support, and because it was the 1960s students were given to protest,” Wolff recalls. That, and unrelated personality tensions with the administration, inspired the mainstreamers to start leaving.

That created openings, which, in 1973, the administration started to fill in an extremely unorthodox way. They decided to hire a “radical package” of five professors: Wolff (then at the City College of New York), his frequent co-author and City College colleague Stephen Resnick, Harvard professor Samuel Bowles (who’d just been denied tenure at Harvard), Bowles’s Harvard colleague and frequent co-author Herbert Gintis, and Richard Edwards, a collaborator of Bowles and Gintis’s at Harvard and a newly minted PhD. All but Edwards got tenure on the spot.

…Under those five’s guidance, the department came to specialize in both Marxist economics and post-Keynesian economics, the latter of which presents itself as a truer successor to Keynes’s actual writings than mainstream Keynesians like Paul Samuelson. “When I got there, the department basically had three poles,” said Gerald Epstein, who arrived as a professor in 1987. “There was the postmodern Marxian group, which was Steve Resnick and Richard Wolff, and then there was a general radical economics group of Sam Bowles and Herb Gintis, and then a Keynesian/Marxian group. Jim Crotty was the leader of that group.” Suffice it to say, most mainstream departments have zero Marxists, period, let alone Keynesian/Marxist hybrids or postmodern Marxists.

Seminal books for each decade

Andrew asks a tough question:

what do you think is more or less the equivalent of the great gatsby in every decade after the 20s?

Here are my picks:

1930s: The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck.

1940s: Farewell, My Lovely, by Raymond Chandler.

1950s: Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison, with Kerouac’s On the Road as a runner-up.

1960s: Catch-22, by Joseph Heller, with The Bell Jar and Herzog as runners-up.

1970s: This is tough. There is Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions, Stephen King, and even Peter Benchley’s Jaws. I’ll opt for Benchley as a dark horse pick, note that these aren’t my favorites but rather they must be culturally central. Jonathan Livingston Seagull is another option, as this truly is an era of popular literature.

1980s: Tom Wolfe, The Bonfire of the Vanities.

1990s: The Firm, by John Grisham, or Barbara Kingsolver, The Poisonwood Bible. Maybe Brokeback Mountain.

2000s: Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point.

Why are more colleges rewarding professorial research?

Dahlia Remler and Elda Pema are studying this question (do you know of an ungated copy?) but they don't yet have clear answers:

Higher education institutions and disciplines that traditionally did

little research now reward faculty largely based on research, both

funded and unfunded. Some worry that faculty devoting more time to

research harms teaching and thus harms students’ human capital

accumulation. The economics literature has largely ignored the reasons

for and desirability of this trend. We summarize, review, and extend

existing economic theories of higher education to explain why

incentives for unfunded research have increased. One theory is that

researchers more effectively teach higher order skills and therefore

increase student human capital more than non-researchers. In contrast,

according to signaling theory, education is not intrinsically

productive but only a signal that separates high- and low-ability

workers. We extend this theory by hypothesizing that researchers make

higher education more costly for low-ability students than do

non-research faculty, achieving the separation more efficiently. We

describe other theories, including research quality as a proxy for

hard-to-measure teaching quality and barriers to entry. Virtually no

evidence exists to test these theories or establish their relative

magnitudes. Research is needed, particularly to address what employers

seek from higher education graduates and to assess the validity of

current measures of teaching quality.

Here is an excellent summary of the piece, with discussion.

Can MR readers set them straight? One hypothesis is that donors prefer to affiliate with research rather than with higher teaching loads and, until the financial crisis, donors have been rising in importance for many universities.

You might also claim that faculty prefer to do research, but why are faculty getting their way more than before? (And why don't faculty just take the lower teaching load without the research requirement, if they are in charge of this evolution?) Or are you wishing to claim that research ability is a good proxy (the best available proxy?) for teaching ability? I doubt that.

My hypothesis draws on the tipping point idea. Due to coalitional politics, it's hard to keep a happy medium, so the most valuable members of the department, whether defined in terms of teaching or research, push for higher research standards than they might otherwise privately favor, if they could have their way. (This happens in both "research-teaching" departments and research departments.) They fear that turning the keys over to "the barbarians" won't much improve teaching either. Research prowess is one of the most efficient bases for organizing competing coalitions. Didn't Dr. Seuss write a novel about this?

Ideally there should be a better way to keep down the losing coalition but it

is hard to find and implement in an incentive-compatible fashion.

One implication is that when growth is high, relatively tough research standards are needed to keep down the losing coalition. When personnel is stagnant or shrinking, the emphasis on research may be less necessary because there is less chance of a shift in power.

Sao Paulo is banning outdoor advertising

Imagine a modern metropolis with no outdoor advertising: no billboards,

no flashing neon signs, no electronic panels with messages crawling

along the bottom. Come the new year, this city of 11 million,

overwhelmed by what the authorities call visual pollution, plans to

press the “delete all” button and offer its residents an unimpeded view

of their surroundings…The outsized billboards and screens that dominate the skyline,

promoting everything from autos, jeans and cellphones to banks and sex

shops, will have to come down, as will all other forms of publicity in

public space, like distribution of fliers.The law also

regulates the dimensions of store signs and outlaws any advertising on

the sides of the city’s thousands of buses and taxis.

Here is the full story. As far as I can tell (my last visit was eight years ago, however), most of it is not down yet. In any case I suspect the city is more attractive with the commercial angle. The underlying buildings are mostly ugly, so a fanciful clutter will do better than an attempt at sleek postmodernism.

By the way, it was already the case that most of Sao Paulo’s 13,000 or so outdoor billboards were installed illegally. The goal is to clear the space entirely, so that any single offender sticks out very obviously and can be prosecuted. But of course the tipping point matters. Whatever change ends up in place, I expect a slow creep back towards the status quo ex ante.

Random rants about books

Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. I am a big fan of what Acemoglu is trying to do, namely integrating history with an economic account of the rise of the West. But this doesn’t work as a book. There is too much thicket and they should have been forced to cut the equations.

George Lodge and Craig Wilson, A Corporate Solution to Global Poverty: How Multinationals can Help the Poor and Invigorate Their Own Legitimacy. The title is wonderful, but this boils down to a call for a World Development Corporation, a’ la Felix Rohatyn but on a global scale. Underargued.

Leonard Susskind, The Cosmic Landscape: String Theory and the Illusion of Intelligent Design. He makes bold claims: for instance Everett’s Many Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics might be identical to the multiverse of some versions of inflation theory. He seems to be making all this up, but I applaud the boldness. I wouldn’t have understood the truth anyway.

Daniel Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomena. What is left to be said? Our beliefs are endogenous, so how can we trust our beliefs? We can’t.

Kyle Gann, Music Downtown, Writings from the Village Voice. I loved this book, but you won’t. For people who think Philip Glass and Robert Ashley are geniuses.

Tom Wolfe, I am Charlotte Simmons. His first mega-novel to fail. None of the dialogue rings true and the author comes across as a dirty old man.

Jose Saramago, Blindness. The Death of Ricardo Reis may be his deepest book, but this is the one most guaranteed to impress. To appreciate him, you have to get over the fact that most of his novels are boring stinkers.

Agatha Christie, And Then There Were None. Does anyone find this suspenseful? I didn’t. But I loved the film when I was ten.

John Banville, The Sea. No way did this dirge deserve the Booker Prize. That pick was strictly a lifetime achievement award.

Stephen King, Song of Susannah. I adore I-IV of The Dark Tower series, but by this point the plot has fallen apart.

Robert Wuthnow, American Mythos: Why Our Best Efforts to Be a Better Nation Fall Short. He is a remarkably powerful mind, but in this book he is spinning his wheels.

Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point. I reread this one, just to remind myself how beautifully constructed it is.

Toni Morrison, Beloved. I used to hate this book, but now I see the appeal. Read Part Three first and work backwards.

Isaac Asimov, The Naked Sun. Excellent. I had never read this one, and don’t forget that his robot stories are commentary on Judaic theology and law.

A profile of Malcolm Gladwell

Author of The Tipping Point, and the forthcoming Blink, Malcolm Gladwell is one of the most influential economic (and social) journalists today. Whatever I see by him I read immediately; I enjoyed this profile as well. Learn why he receives $40,000 per lecture. And if you don’t know Gladwell’s work, here is an archive of his articles.

Thanks to www.geekpress.com for the pointer.

Tale of two condiments

Why has mustard in the United States improved so much, but ketchup has stayed largely the same? Why are some sectors more prone to innovation than others? What constrains innovation from the consumer side?

Here is Malcolm Gladwell’s excellent account from The New Yorker. Here is an archive of his writings for the magazine; he is also author of the best-selling The Tipping Point. Check out Gladwell’s work if you don’t already know it.

Suicide and multiple equilibria

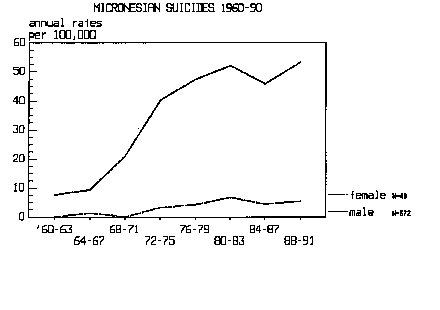

I don’t aim to be the cynical economist that Tyler writes “might suggest social stigma for suicide, rather than forgiveness” but it is frightening how easy it seems to be to jump to the sad equilibrium. The story of suicide among young boys in Micronesia (I recommend Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point for a discussion but will cite some online material) illustrates how actions and social attitudes reinforce one another. As the action becomes more common, perhaps reaching a “tipping point”, condemnation declines, and the action increases even further. Here, from one of the researchers who first documented the story, is a chilling description of suicide in Micronesia:

As suicide has gained familiarity among youth, the act itself has become increasingly more acceptable or even expected. Suicides appear to acquire a sort of contagious power. One suicide might serve as the model for successive suicides among friends of the first victim. There has been an apparent increase in suicides among very young children, aged 1ï¼-14. Evidently the idea of suicide has become increasingly commonplace and compelling, and young children are now acquiring this idea at earlier ages.

Another of the earlier researchers writes:

Love songs mention suicide, youths discuss the subject openly among themselves and at times make suicide pacts with one another, and youngsters express admiration of those who have taken their own lives and are mourned so terribly by their families and friends. What is even more shocking, however, is that a number of adults in our communities seem to share the belief that these young people have died altruistic and even heroic deaths. If the majority of Micronesians really believe that suicide is an honorable option, then this paper is thoroughly useless and all of us had better resign ourselves to continuing high rates of suicide in the future. Young people, after all, are very quick in sensing the basic values of their elders. If they get the impression that we ourselves honor suicide, then they will be only too happy to oblige by hanging themselves.

Note that one could tell similar stories in the United States about divorce, having children out of wedlock, welfare dependence etc. (also teenage suicide at a local level).

Here is a graph of suicide rates in Micronesia indicating a massive increase in a few short years in the early 1970s. The tipping theory generates credence when we note that virtually all the suicides take a similar, ritualistic form involving hanging.