Month: June 2004

Weekend moviegoing

I saw Hitchcock’s Vertigo yesterday, for about the sixth time in my life. I had forgotten how perverse it is, how much the theme of male impotence and voyeurism runs throughout the movie, how deeply sadistic Jimmy Stewart becomes, and how much the movie flirts with the theme of doubles (compare Scotty and Kirby, for instance, or think about Scotty’s ex-beau). I’ve been watching “Japanese extreme” cinema lately, films such as Audition, which have to be seen to be believed. Vertigo is at least as sick as any of those. Vertigo also has the most successful integration of cinematography and musical score that I’ve seen. Watch it again if you can, especially if it is shown on a big screen.

Facts about pets

1. There are 65 million dogs in the US and 77 million cats.

2. Seventy-six million households own a pet (roughly 3 in 4).

3. We will spend $34 billion on pets in 2004 (up from $17 billion in 1994): $1.6 b. on the pets themselves, $14 b. for food, and $8 b. for veterinarian care.

4. There are slightly more male dogs than female dogs and slightly more female cats than male cats. This suggests that we honor the cultural notion that dogs are “male” and cats as “female.” What happens to the animals that do not fit this gender profiling? You don’t want to know.

5. Some owners of Vietnamese Pot-bellied pigs found their new pets too aggressive, and they did something surprising. They took them to a slaughter house. Then they did something really surprising. “In some cases, the owners took the meat from their pigs home, which certainly goes against our traditional thinking about what we do with our pets.”

6. …more than 60 percent of cat and dog owners include news about their pets in their holiday greetings, 27 percent take their pets along for family photographs and pictures with Santa, and 79 percent give their pets holiday or birthday presents.

7. “89 percent of pet owners believe that their pet understands all or some of what they say.” [Read here for more.]

These are all quotations from the ever-excellent Grant McCracken. Grant concludes:

We have taken our peculiar idea of the person and conferred it on our pets. This is an exceedingly odd and interesting transformational exercise. After all, these animals are by human standards deeply stupid. When we treat them as persons, we engage in an astonishing act of metamorphsis. But implausibility does not discourage us. We are a nation of individuals and we have decided that our pets are going to be individuals, too.

Grant is an anthropologist who writes about the boundaries of anthropology, culture and economics. For something slightly more prurient by him, (but still PG-13), read his post on the economics of the bare mid-riff.

Has Bush cut back government bureaucracy?

The following table lists how many of the major agencies or departments had their budgets cut in a given Presidential term:

President and Term, Number of Budget Cuts [see the last link in this post for further explanation of the data. I’ve done minor editing and added the boldface]

Johnson, 4 out 15

Nixon, 3 out 15

Carter, 5 out 15

Reagan 1, 8 out 15

Reagan 2, 10 out 15

Bush, George H., 2 out 15

Clinton 1, 9 out 15

Clinton 2, 0 out 15

Bush, George W., 0 out 15

Obviously Reagan II made real efforts in this direction. George W. comes in tied for last with Clinton II. This is a highly imperfect proxy, but when you are 0 for 15 it is hard to blame measurement error alone.

Here is one unnoticed achievement of Ronald Reagan:

President Reagan is the only president to have cut the budget of the Department of Housing and Urban Development in one of his terms (a total of 40.1 percent during his second term).

Here is the full and sad story on Bush’s fiscal policy for the agencies and departments. Here are the underlying data.

Department of Uh-Oh

Has the Riemann hypothesis in fact been solved?

A French mathematician is claiming to have solved a fiendishly difficult problem, upon which rides a million dollars of prize money. But other mathematicians are sceptical that he has really done it.

On Tuesday, Louis de Branges de Bourcia, a professor of mathematics at Purdue University in Indiana, issued a press release claiming that he has proved the Riemann hypothesis is true.

This proof is perhaps the most tantalising goal in mathematics today. If true, it tells us that prime numbers, which are those exactly divisible only by one and themselves, are scattered utterly randomly along the number line. If not, then mathematicians may be able to predict where the prime numbers fall.

For almost 150 years, mathematicians have been struggling to establish whether or not the Riemann hypothesis holds. And de Branges has claimed to have solved the problem before, only for others to later find flaws in his work.

“For the past 15 years he has been periodically announcing a proof and posting preprints” says Jeffrey Lagarias, a mathematician at AT&T Labs in New Jersey, who has followed de Branges’ work.

Here is the full story.

Gas prices and the demand for new cars

Yesterday, I test drove a Toyota Prius, the high-tech gas-electric vehicle that gets up to 60 mpg. After the test drive, the salesperson told me that demand was so high there was a 6 month wait.

Can art trusts work?

One reader wrote me the following:

…artists who put works into the pool are depositing them at full value, tax free, right? If they instead sold these works, they’d lose 50% to a gallery and then another 50% (the marginal tax rate of any minimally successful self-employed person, even me) to Uncle Sam etc. In other words, if they sold art and invested the cash they’d only have 25 cents on the dollar to put into stocks and bonds. The question is whether any money manager could overcome this enormous handicap.

Besides, most artists tend to have more works than they can sell into such an inefficient market. For this and the reasons above, the cost of contributing to this fund may be close to zero for all but the most wildly successful participants.

What does it cost to set an art work aside?

Let’s say that the art trust can store the work at the same cost as a gallery. Then the artist already has done all the storing that he or she wants to do. Storing more works, all other things equal, is a cost rather than a benefit. And tax must be paid once the works are sold, in any case. Furthermore, when it comes time to sell the works and get the best price possible, the trust is no more effective than a gallery, and arguably less so. In fact the trust might resort to a gallery or auction house in any case, simply postponing the selling costs.

Perhaps the artist has pictures that he cannot sell at all. Why not put them into the trust? Fair enough, but if no gallery will take these pictures, how can the trust make them profitable?

The deal makes the most sense when an artist currently has an exclusive dealing agreement with a gallery. Such an artist might prefer to siphon off works to other channels, as a form of price discrimination, but is not allowed to. The sponsoring gallery does not want its market to be ruined. The trust might allow the artist to achieve market segmentation without it being labeled as such.

Nonetheless the artist pays a price for this new outlet. You have to accept a risk position in the pictures of others. Furthermore this price discrimination motive suggests that each artist will be putting his lesser pictures into the trust. You don’t want to “shade price” on your very finest pictures.

Another reader wrote:

I’m not persuaded that the art trust wouldn’t be an effective model. It doesn’t seem a lot different than the risk dilution idea of a blackjack team or the cross-trading that goes on between friends in a large poker tournament.

Again, a very good point. But you wish to share risk in this fashion when you know that you (and your team) can beat the market. In this case you are confident but want protection against bad luck. If you felt that the artists in the pool were all above-average, relative to their current prices, you might find the trust attractive. This would require each artist to judge the other artworks in the pool, which involves high information costs.

Perhaps the trust helps solve a “durable goods monopolist game.” That is, the artist wishes to precommit not to sell works in the near future. Buyers may be afraid that if they buy today, the price will be lower tomorrow. Perhaps the trust can take works off the market more effectively than a gallery can. This would provide some argument for the trust. But of course the artist must also prove to buyers that he has locked up his future output to the requisite degree; this may prove difficult.

A final issue is one of trust in the intermediary. Life insurance, or savings banks (pre-deposit insurance), promise to pay you back in a distant future. Virtually all depositors or policyholders have preferred large, solid institutions with high levels of capitalization. Older banks had fancy columns to signal they will be around for the long run. Otherwise there is simply too much risk that a small intermediary will go under. If you are “lending” a painting to an artistic venture, why not look for the most conservative and thickly capitalized institution possible?

In closing, I will repeat my bottom line from my previous post on the topic:

…decompose the transaction. Half of your income stream remains tied up in your own art and thus risky, minus the twenty percent of course. With the other half of your pension you decide to invest in not-yet-totally-famous artists. Would anyone recommend such purchases on their own merits? Is that your idea of insurance?

That being said, it is the market, not I, who will have the final word in this matter.

The future of Europe?

Every time I go to Europe I wonder what kind of future the place has:

1. The average American consumes 77 percent more than the average citizen of EU-15, read here.

2. Germany has recently failed in its attempt to reform the country’s antiquated store closing laws. German shops, with some exceptions, cannot stay open later than eight at night or on Sundays or major holidays. The German public strongly opposes these laws, but the small shop lobby dominates.

3. A recent survey in France suggests that 70 percent of French schoolchildren aspire to become bureaucrats rather than captains of industry. (See the IHT, June 9, “Divided We Graumble,” by Roger Cohen, p.2.)

4. The beauty of European cities typically stems from 1920 or earlier, when much of Europe was economically freer than the United States. How would U.S./Europe comparisons feel to us if all of Europe had been built after the second World War? How many people would then think that the “European way of life” is superior.

5. Guido Tabellini (FT, June 3) tells us that Europeans consume more leisure because they find it harder to get good jobs, not because of a cultural preference for the finer things in life.

6. The major European economies face serious demographic problems and have a hard time pushing much above a one percent growth rate. Americans call it a recession when our rate of growth falls to a mere two percent.

Hey, wait a minute:

American investment in the European Union is at an all-time high. So how bad can things be?

This is what makes economics an interesting science. My best guess is that it is easier than ever before to free-ride on the productivity and ingenuity of your neighbors. This is a great benefit of globalization, but it also makes it too easy for economies to postpone needed reforms.

That being said, here are further grounds for hope.

Crowds are wiser than you think

I’m reading James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds – so far, it’s very good! Steve Sailer posted the following comment on the book:

…he doesn’t really explain why pseudo-markets like the Iowa Election Market tend to be more accurate than traditional predictive tools like the Gallup Poll, although the answer is obvious: because they piggyback off traditional sources of information like Gallup. For example, participants in the IEM look at not just the Gallup Poll but a dozen others. Without these pollsters spending large amounts of money to generate information, however, the market players would be pretty clueless. Similarly, if the crowd takes the average of the 11pm weather forecasts of the weatherguys on Channels 2, 4, and 7, they may well beat the best individual forecast, but that doesn’t mean the crowd could beat the professional weathermen — unless the pros first tell them what they think the weather is going to be.

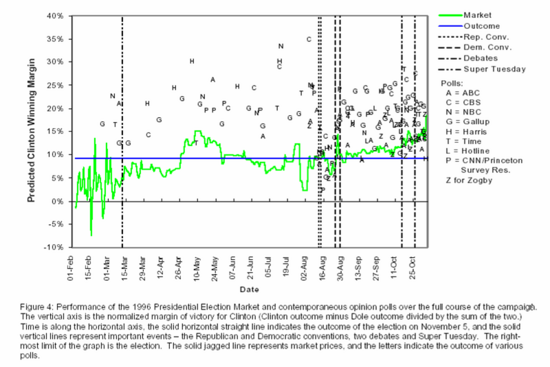

Clearly, there is some truth to this – Hayek said markets are “marvelous” he didn’t say “miraculous.” But a lot more goes on in information markets than averaging. The green line in the figure below (click to expand) shows the Iowa market prediction for the 1996 Presidential election. The blue line is what actually occured. The spots are various polls. Now notice that from February through August every single poll overpredicted Clinton’s victory and every single poll, with but one exception, was above the market prediction. This means that the market prediction could not possibly be an average of the polls.

Surowiecki gives a number of other examples where the wisdom of the crowds cannot be explained by averaging of expert opinion even though averaging is an important reason why crowds can be wise.

Global warming links

Courtesy of Jane Galt. The upshot of her post is that the problem is very very hard to solve.

I thought that The Day After Tomorrow, which I saw in Poland, had more bad cliches than perhaps any other movie I have seen, ever. The bad science is actually one of the least ridiculous things about the movie.

Did you know that the film had the widest “day-and-date” release in movie history? (See June 7-13 Variety, p.12.) It topped 108 markets at the same time, in early June. It failed to earn the number one spot in Greece and Serbia, however. Can you guess why?

How many words can your dog understand?

If it is a collie, perhaps up to 200 words.

The researchers found that Rico knows the names of dozens of play toys and can find the one called for by his owner. That is a vocabulary size about the same as apes, dolphins and parrots trained to understand words, the researchers say.

Since dogs-as-we-know-them co-evolved with humans, I don’t find this surprising. More generally, we underrate the intelligence of many animals. But even I found this part hard to believe:

Rico can even take the next step, figuring out what a new word means.

The researchers put several known toys in a room along with one that Rico had not seen before. From a different room, Rico’s owner asked him to fetch a toy, using a name for the toy the dog had never heard.

The border collie, a breed known primarily for its herding ability, was able to go to the room with the toys and, seven times out of 10, bring back the one he had not seen before. The dog seemingly understood that because he knew the names of all the other toys, the new one must be the one with the unfamiliar name.

Here are some of the words that Rico understands. Keep in mind that this dog understands only German, the text is translated. Note also that most “tricks” (remember Hans the horse?) still represent some form of communication with the animal.

Here is another summary report. And yes, the work is published in the highly respected journal Science, in case you were wondering.

On a related note, I just read (and recommend) this book on how animals talk to each other.

A basket for weaker currencies?

Mr [Barry] Eichengreen spells out…an ingenious plan…he proposes the creation of a market for lending and borrowing in a synthetic unit of account, a weighted basket of emerging-market currencies. Such bonds would be popular with investors, since the currency would be more stable than the sum of its parts and, at first at least, carry attractive yields. Importantly, such a market, if it could be established, would eventually let emerging-market economies tap foreign capital without currency mismatches. This is because those, such as the World Bank, that issued such bonds would be keen to reduce their exposure to the basket by lending to the countries in that basket in their own currencies.

The idea is to prevent a mismatch between assets and liabilities:

…some countries’ financial fragility results simply from their need for foreign investment. In the most susceptible countries, firms and banks borrow heavily in dollars, while lending in local currencies. If the value of the local currency wobbles, this mismatch between domestic assets and foreign liabilities is cruelly exposed.

Why are the assets and liabilities of emerging markets so ill matched?…International investors are very choosy about currencies. Most consider only bonds denominated in dollars, yen, euros, pounds or Swiss francs. This select club of international currencies is locked in for deep historical and structural reasons. Thus, poor countries that want to borrow abroad must bear currency mismatches through no fault of their own.

I have no problem with trying the idea, but what can we expect?

First, it remains a puzzle why lenders are reluctant to denominate international loans in anything but the five major currencies (dollar, Euro, yen, sterling, and Swiss franc). So it is hard to know whether another unit of account could join this exclusive club. Perhaps investors would find the basket hard to evaluate or simply unwieldy. They might not want the basket any more than they would lend in Brazilian real, which is the original source of the problem.

Second, say that the basket did become widely used and relatively stable. Underdeveloped countries would then have their liabilities in a stable unit of account but their assets would still fluctuate in value. We would return to a version of the original problem. Now one might hope that the basket-denominated debts would be swapped back into the local currency. But I don’t see any particular reason why such swaps would increase in ease.

Third, if the basket becomes more liquid than its underlying components, the system may be vulnerable to arbitrage and speculation opportunities. Whether these would be stabilizing remains an open question. In essence the price of the basket would tell you where the underlying components are headed. We would have a new version of the “stale pricing” problem.

The Eichengreen proposal represents an old dream, and one that I have been taken with myself: improve risk-sharing simply by creating a new nominal value. This may sound like economic alchemy, but hey, it worked with stock index futures. That being said, in this arena the number of failures far outweighs the number of successes.

Here is one summary of the plan. Here is a useful summary by Eichengreen and Haussman.

Thanks to Chris Danford for the pointer.

Has the Riemann hypothesis been solved?

Maybe. Of course there have been false alarms before. The Riemann hypothesis, often considered the greatest unsolved problem in mathematics, concerns whether the distribution of prime numbers has a particular order.

Here is one summary of the problem; here is another, with some more technical links.

You can check out the would-be proof yourself.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe continues its short march into barbarism. Here’s is a quote from land minister John Nkomo – sadly reminiscient of early twentieth century history.

Ultimately, all land shall be resettled as state property. It will now be the state which will enable the utilization of the land for national prosperity.

Of course, he was quoted in the government controlled newspaper. And get this, it’s not good enough that the government take the land:

Mr. Nkomo urged farmers to volunteer their land to the state rather than wait for an order, saying, “The state should not be made to waste time and money on acquisitions.”

The people of Zimbabwe are starving because of land “redistribution” could a better example of Robert Lucas’s dictum be found?

Immigration and 9/11

One of the few bright notes since 9/11 is that there has been no backlash against immigrants. Consider, for example, that there were 25 percent more immigrants to the United States in 2002 than in 2000 (see Table 1). Nor has there been an immigration backlash against Muslims – there were 19 percent more immigrants, for example, from Iran in 2002 than 2000 (see Table 2). Even more surprising, despite heightened examination, 20 percent fewer aliens were expelled from the United States in 2002 than in 2000 (see Table 43).

China facts

1. Chinese per capita income in 2003 is roughly seven times higher than in 1978.

2. In 2002, in purchasing power parity terms, China accounted for twelve percent of global gdp.

3. The figure drops to only four percent, if we calculate real gdp by exchange rates rather than purchasing power parity.

4. In 1952, Communist China claimed to comprise five percent of global gdp.

2. China accounted for one-third of world economic product in 1820. The figure is from work by Angus Maddison.

These facts are drawn from Tuesday’s Financial Times, an Op-Ed entitled “China is Not Racing Ahead, Just Catching Up.”

Addendum: Bruce Bartlett refers me to Maddison’s data.