Month: October 2004

A Nobel for Real Business Cycles

Tyler has commented on the time-consistency problem so I will post on the other contribution for which Kydland and Prescott were awarded the Nobel, real business cycles. (I see now that Tyler also has a post on real business cycles – that guy is fast!.)

Recessions have almost always been thought of as a failure of market economies. Different theories point to somewhat different failures, in Keynesian theories it’s a failure of aggregate demand, in Austrian theories a mismatch between investment and consumption demand, in monetarist theories a misallocation of resource due to a confusion of real and nominal price signals. In some of these theories government actions may prompt the problem but the recession itself is still conceptualized as an error, a problem and a waste.

Kydland and Prescott show that a recession may be a purely optimal and in a sense desirable response to natural shocks. The idea is not so counter-intuitive as it may seem. Consider Robinson Crusoe on a desert island (I owe this analogy to Tyler). Every day Crusoe ventures onto the shoals of his island to fish. One day a terrible storm arises and he sits the day out in his hut – Crusoe is unemployed. Another day he wanders onto the shoals and he finds an especially large school of fish so he works long hours that day – Crusoe is enjoying a boom economy. Add to Crusoe’s economy some investment goods, nets for example, that take “time to build.” A shock on day one will now exert an influence on the following days even if the shock itself goes away – Crusoe begins making the nets when it rains but in order to finish them he continues the next day when it shines. Thus, Crusoe’s fish GDP falls for several days in a row – first because of the shock and then because of his choice to build nets, an optimal response to the shock.

An analogy is one thing but K and P showed that a model built from exactly the same microeconomic forces as in the Crusoe economy could duplicate many of the relevant statistics of the US economy over the past 50 years. This was a real shock to economists! There are no sticky prices in K & P’s model, no systematic errors or confusions over nominal versus real prices and no unexploited profit opportunities. A perfectly competitive economy with no deviations from classical Arrow-Debreu assumptions could/would exhibit behavior like the US economy.

Models like K & P’s called dynamic, stochastic, general equilibrium (DSGE) models are now the standard in macroeconomics but today they may also include demand side shocks and sticky prices as well as real shocks. Thus thesis has met anti-thesis and the synthesis has demand and supply shocks both contributing to business cycles.

Addendum: More at the Nobel site.

Why real business cycle theory is important

Most nineteenth century theories of the business cycle were real (non-monetary) in nature, often involving agricultural causes. The harvest is bad and next thing you know, the economy stands in ruins. A pretty good theory when agriculture accounts for more than half of gdp. The Swede Knut Wicksell stood at the peak of this tradition, although he used changes in the natural rate of interest as a more general way of thinking about the initial real shock. In the basic Wicksellian story, a decline in the real rate of return causes entrepreneurs to contract their economic activity. Money and credit contract as well, leading to a downward “cumulative process.”

Real business cycle theory to some extent went underground during the “years of high theory.” Both Hayek and Keynes, while they drew from Wicksell, diverted our attentions away from traditional real business cycle theory mechanisms. Hayek blamed monetary expansion, while Keynes focused more on issues of animal spirits and liquidity premia, and sometimes sticky prices. Kalecki and others worked on the real approach, but it lost its professional centrality.

The rational expectations revolution of the 1970s led us back to real approaches. If people anticipate the future with a fair degree of accuracy and rationality, money will likely be neutral or close to neutral. Furthermore if all markets clear, there should be no room for sticky prices and wages. So what else is left other than real theories of the business cycle?

Any business cycle theory, real or not, must account for at least two generalized phenomena of business cycles: persistence (the cycle is not over right away but rather drags on) and comovement (many sectors of the economy move together). Kydland and Prescott were among the first people to see this problem (kudos to Long, King, and Plosser as well), and among the first to address it.

Kydland and Prescott wrote a seminal article (Econometrica 1982) about “Time to Build and Aggregate Fluctuations.” They resurrected the old Austrian concept of a “period of production.” But rather than engaging in the metaphysics of capital theory, they ran some simulations. They showed that if production takes time, an initial negative shock can cause lower inputs and outputs over a longer period of time. Furthermore they showed that reasonable assumptions about parameter values can lead this mechanism to fit the real world. This article made an immediate splash, and rightly so.

Now today the purely real approach to business cycles no longer stands. Wage and price stickiness now play some role in virtually all business cycle theories, if only because labor market data otherwise appear inexplicable. But you might also say that today “we are all real business cycle theorists.” Most economists subscribe to a hybrid theory involving monetary shocks, real shocks, and imperfect adjustment mechanisms. All of these theories, to some extent or another, rely on the real transmission mechanisms outlined by Kydland, Prescott, and others.

Kydland and Prescott: New Nobel Laureates

This year’s Nobel Prize in economics went to Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott . Kydland and Prescott wrote a famous 1977 piece (Journal of Political Economy) on time inconsistency. Ever wonder why government policy toward prescription drugs is so problematic? Kydland and Prescott had the answer. The optimal policy will first award the drugmakers a patent and allow them to charge a high price. But once the drug is developed, the “rents” will be confiscated. Optimal policy will revoke the patent and lower the price. After all, once you have the drug. why not let everybody have it cheaply? Of course the drugmakers are aware of this danger in advance, and they are correspondingly reluctant to develop new drugs. Alex posted on this logic just days ago.

In more formal language, the optimal policy is not a time consistent policy. This develops earlier ideas from Thomas Schelling on game theory. Schelling’s point was that nuclear deterrence can fail because, once destruction is aimed your way, you don’t necessarily wish to retaliate.

The logic of time consistency is quite general. It applies to regulatory policy issues, tax policy, monetary policy, foreign policy (threaten Saddam, but do you really want to have go to through with it?), and strategic behavior in a wide variety of settings.

Here are my earlier comments on Prescott, which link to other facets of his work. He arguably has enough contributions to win the prize twice. Kydland is less well known but is an important figure nonetheless. And it doesn’t hurt that he is Scandinavian (Norwegian).

Are the pair deserving? Absolutely yes.

Why did they win this year? I’m guessing that in the midst of a partisan U.S. election, the Swedes did not want to pick Paul Krugman or Robert Barro (pro-Bush), for fearing of appearing too political. Note that the economics prize has stood under criticism for some time now, for not being “scientific” enough.

And this pick the betting market got right. Prescott had opened up a clear lead in the betting market some time ago.

The limits of consumer choice

It’s acceptable for consumers to use software that edits out nudity or bad language from a DVD movie — but they had better leave the commercials and promotional announcements in, according to legislation adopted by the House of Representatives this week.

Here is the full story.

It is easy to see how this differential treatment might be efficient. Sex-edited DVDs increase market value by giving some parents a choice. Yet at the same time ads in DVDs help fund new issues; if consumers found the ads too burdensome the DVD makers would leave them out (admittedly the marginal consumers may not represent the interests of the market as a whole, but this is a special case).

Yet many people — myself included — feels a twinge of disapproval, or perhaps even slight rage, on reading the quotation above. It reflects how our intuitions are programmed to reflect views about autonomy and control: “How come prudish moralists can remove artistically vital movie segments, but hip culture fiends cannot eliminate the offensive abominations known as commercials?”

The prudes gain control, the artists and film directors lose control over their product, and the culture fields are stuck with their initial level of control. It seems that only the “unworthy” gain autonomy, therefore the idea must be a bad one. Yet, as stated above, the policy probably maximizes economic value.

The bottom line: Our moral intuitions have only a very loose connection to long-run efficiency, especially when impersonal market forces are involved, and someone bears an annoying cost (i.e., commercials) in the short run.

Addendum: One of my readers cites the long-run elasticity of prudishness, in an attempt to reconcile our intuitions with efficiency. If edited DVDs lower the cost of being an (interfering) prude, they may not be so good after all.

The history of life, on a postcard?

Will your children see an exponential growth explosion? Here is Robin Hanson’s latest:

A revised postcard summary of life, the universe, and everything, therefore, is that an exponentially growing universe gave life to a sequence of faster and faster exponential growth modes, first among the largest animal brains, then for the wealth of human hunters, then farmers, and then industry. It seems that each new growth mode starts when the previous mode reaches a certain enabling scale. That is, humans may not grow via culture until animal brains are large enough, farming may not be feasible until hunters are dense enough, and industry may not be possible until there are enough farmers.

Notice how many “important events” are left out of this postcard summary. Language, fire, writing, cities, sailing, printing presses, steam engines, electricity, assembly lines, radio, and hundreds of other “key” innovations are not listed separately here. You see, most big changes are just a part of some growth mode, and do not cause an increase in the growth rate. While we do not know what exactly has made growth rates change, we do see that the number of such causes so far can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

While growth rates have varied widely, growth rate changes have been remarkably consistent — each mode grew from one hundred and fifty to three hundred times faster than its predecessor. Also, the recent modes have made a similar number of doublings. While the universe has barely completed one doubling time, and the largest animals grew through sixteen doublings, hunting grew through nine doublings, farming grew through seven and a half doublings, and industry has so far done a bit over nine doublings.

This pattern explains event clustering – transitions between faster growth modes that double a similar number of times must cluster closer and closer in time. But looking at this pattern, I cannot help but wonder: are we in the last mode, or will there be more?

If a new growth transition were to be similar to the last few, in terms of the number of doublings and the increase in the growth rate, then the remarkable consistency in the previous transitions allows a remarkably precise prediction. A new growth mode should arise sometime within about the next seven industry mode doublings (i.e., the next seventy years) and give a new wealth doubling time of between seven and sixteen days. Such a new mode would surely count as “the next really big enormous thing.”

Read the whole thing. Yes you should pay attention to these ideas; even if their chance of being right is small, their expected value in terms of importance is high. That being said, I sometimes tease Robin for offering us a secular version of Pascal’s Wager.

Note that Robin makes Arnold Kling look like a pessimist.

I’m a Glenn Gould obsessive

Wondrous Strange, the new biography of late Canadian pianist Glenn Gould is splendid, even in a relatively crowded field. If you’re not tuned into the obsession, try Gould’s rendition of Bach’s Partitia #1, in B flat major; this is perhaps my favorite classical music recording of all time. Don’t forget these either.

If only it were true

George Bush during the second debate:

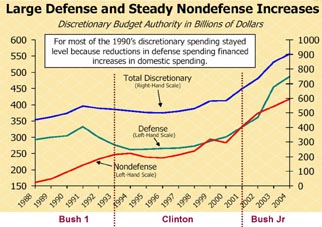

Non-homeland, non-defense discretionary spending was raising at 15 percent a year when I got into office. And today it’s less than 1 percent, because we’re working together to try to bring this deficit under control.

Kevin Drum makes it simple.

Here’s the truth about non-defense discretionary spending over the past six administrations:

Nixon/Ford: 6.8% per year

Carter: 2.0% per year

Reagan: -1.3% per year

Bush 1: 4.0% per year

Clinton: 2.5% per year

Bush Jr: 8.2% per year

All percentages are adjusted for inflation. The chart on the right shows raw figures for the past three administrations (from the Congressional Budget Office).

My goof

In my recent post on pharmaceutical regulation I wrote:

In the pharmaceutical market the major costs are all fixed costs (they don’t vary much with market size) so profit =P*Q-F. Acemoglu and Linn look at changes in Q but a 1% change in P has exactly the same effects on profits, and thus presumably on R&D, as a 1% change in Q.

But as Bernie Yomtov pointed out to me a reduction in P will increase Q. Ugh, an economist who has to be reminded about the law of demand. Embarrassing. The argument goes through if demand is quite inelastic which makes sense for a lot of drugs given that the price to the final consumer is low to begin with due to insurance – nevertheless the result is not so clean. Indeed, because of the envelope theorem a small change in P will have only a very small change in profits. Sadly, I teach this to my students regularly. Did I mention that I have had the flu this week?

Are asset price bubbles good?

“A bubble is good for growth because it creates a low cost environment for experimentation.”

Here is the full argument. I am prepared to believe that the government should not try to regulate or otherwise restrict bubbles. Why should we think that governments can outguess traders? And bubbles help finance socially worthwhile ideas that may not have high private returns. But would I wish that traders had less “bubbly” temperaments?

Thanks to www.politicaltheory.info for the link.

Markets in everything

Who needs an entire boyfriend, when you can have just one part? The Japanese have an answer to this question.

Thanks to Yana for the pointer.

Who benefits from R&D?

…the main finding — that R&D capital stocks of trade partners have a noticeable impact on a country’s total factor productivity — appears to be robust… [consider] a coordinated permanent expansion of R&D investment by 1/2 of GDP in each of twenty-one industrial countries. The U.S. output grows by 15 percent, while Canada’s and Italy’s output expands by more than 25 percent. On average the output of all the industrial countries rises by 17.5 percent. And importantly, the output of all the less-developed countries rises by 10.6 percent on average. That is, the less-developed countries experience substantial gains from R&D expansion in the industrial countries [emphasis added].

That is from Elhanan Helpman’s just-published The Mystery of Economic Growth. I’ll add that, more generally, Europe is a massive free-rider on American investments in pharmaceutical R&D; see Alex immediately below.

Are you looking for a good and readable summary of what economists know about economic growth? Helpman’s book is the place to start. And here is my earlier post on external returns from innovation.

Price Regulation of Pharmaceuticals

How much would a 10% reduction in price reduce pharmaceutical research and development? That is the key question in debates about reimportation of pharmaceuticals from Canada, price controls, and using the power of Medicare to bargain with pharmaceutical companies. In a recent paper from the Quarterly Journal of Economics, Daron Acemoglu and Joshua Linn suggest an answer.

Acemoglu and Linn’s paper is formally about a different issue; the effect of market size on innovation. What they find is that a 1 percent increase in the potential market size for a drug leads to an approximately 4 percent increase in the growth rate of new drugs in that category. In other words, if you are sick it is better to be sick with a common disease because the larger the potential market the more pharmaceutical firms will be willing to invest in research and development. Misery loves company.

Although they don’t mention it, this finding has implications for price controls. In the pharmaceutical market the major costs are all fixed costs (they don’t vary much with market size) so profit =P*Q-F. Acemoglu and Linn look at changes in Q but a 1% change in P has exactly the same effects on profits, and thus presumably on R&D, as a 1% change in Q.

[I no longer think the above is correct but I leave it here for the historical record, see My goof.]

We can expect, therefore, that a 1% reduction in price will reduce the growth rate of new drug entries by 4% and a 10% reduction in price will reduce new drug entries by 40%. That is a huge effect. I suspect that the authors have overestimated the effect but even if it were one-half the size would you be willing to trade a 10% reduction in price for a 20% reduction in the growth rate of new drugs? No one who understands what these numbers mean would think that is a good deal.

Fannie Mae update

Daniel Gross explains the risks of Fannie Mae:

Fannie Mae has convinced itself that massive exposure to interest-rate volatility can be a low-risk business. It has propounded the notion that a giant financial company, through efficient hedging, can produce earnings that are as smooth and predictable as those reported by General Electric in Jack Welch’s heyday. The people who owned Fannie’s stock–worth $74 billion just two weeks ago–explicitly bought into this belief.

The desire to have earnings conform to some pre-existing plan is a recipe for trouble at a large corporation. One of the most damning segments of the OFHEO report (see Pages 7-12) discusses how, in order to be perceived as low risk, Fannie felt it had to present regular earnings growth. The meeting of earnings goals was so crucial that bonuses for top executives were pegged to them. In 1998, bonuses were based on hitting targets: earnings of $3.13 a share for the minimum bonus, $3.18 for the target bonus, and $3.23 or above for the maximum bonus. “Remarkably the 1998 EPS number turned out to be $3.2309,” OFHEO deadpans. In order to meet the target, OFHEO suggests, Fannie Mae may have improperly deferred some $200 million in expenses.

When it comes to risk, as with everything else, there is no free lunch (with apologies to Kenneth Arrow). Read the whole thing. And here is my previous post on Fannie Mae.

New economics and public policy blog

VoxBaby this one is called, and it is written by Andrew Samwick, a first-rate economist at Dartmouth. His research covers such diverse areas as executive compensation, social security reform, and pension reform. We welcome Andrew to the blogosphere.

Markets in everything

A woman [Yuolanda Taylor] who police say sold stones to rioters in a southwest Michigan city last year and used the money to pay her cable television bill has pleaded no contest to inciting a riot.

Police said Taylor toted rocks through a riot-wracked neighborhood, selling small ones for $1 each and bigger ones for $5. Prosecutors said the rocks were thrown at police.

Taylor told police she collected about $70 selling rocks, but quit when she got hit by one herself.

Here is the full story. Thanks to blogger John Wilson for the pointer.