Month: February 2013

*Sharing the Prize*

That is the new and much awaited book by Gavin Wright, with the subtitle The Economics of the Civil Rights Revolution in the American South. Here is one small bit, reflecting some of the book’s main themes:

By the 1930s, labor markets in the South had come to display a distinct “racial wage gap,” supported by systems of vertical workplace segregation. Not only were job categories classified by race, but black wage rates typically peaked about where white pay grades began. These structures persisted through World War II and the 1950s, showing few signs of softening even in the presence of rapid urbanization and industrial employment growth.

Here are some related powerpoints by Wright (pdf). Here is the book’s home page.

The composition of unemployment into short- and long-term

This is not new news, but Peter Coy frames it quite memorably:

The rate of short-term unemployment—six months or less—is almost back to normal. In January it was 4.9 percent of the labor force. That’s only 0.7 percentage point above its 2001-07 average. But the rate of long-term unemployment, 3 percent in January, is precisely triple its 2001-07 average, according to a Bloomberg Businessweek calculation based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data. (Those two rates—4.9 percent and 3 percent—add up to the overall unemployment rate of 7.9 percent.) A striking statistic: The long-term unemployed make up 38 percent of all workers without jobs, double the average share and just a few notches down from the 2010-11 peak of 45 percent.

That is another way to think about why rapid labor market improvement appears unlikely.

The new New Republic

I thought I would wait until the second issue before offering an opinion. I really like it. I like almost everything in there, though I thought the opening issue interview with President Obama was a bit of a softball. They have kept the genius of Jed Perl and they appear to have culled some of the weaker writers from the previous incarnation. I can imagine reading almost everything they are printing, even if I don’t always get to it. It still feels like The New Republic in a useful way.

Their web site is here, although there is much more in the print edition (I don’t yet understand their policies for when things go on-line, noting that the blame there probably lies with me).

I hope Chris Hughes knows that my liking it probably means it is financially doomed. And I fear that its being good may not matter so much any more.

Krugman’s response on cash hoarding

Krugman, in a response, accuses me of not understanding Keynes’s critique of Say’s Law:

Cowen can’t see why corporate hoarding is a problem. Like Riedl and Cochrane, he concedes that there might be some problem if corporations literally piled up stacks of green paper; but he argues that it’s completely different if they put the money in a bank, which will lend it out, or use it to buy securities, which can be used to finance someone else’s spending.

Let’s look at what I actually wrote:

Maybe you are less impressed if say Apple buys T-Bills, but still the funds are recirculated quickly to other investors. This may not end in a dazzling burst of growth, but there is no unique problem associated with the first round of where the funds come from. If there is a problem, it is because no one sees especially attractive investment opportunities in great quantity. (To the extent there is a real desire to invest, the Coase theorem will get the money there.) That’s a problem at varying levels of corporate profits and some call it The Great Stagnation.

The same response holds if Apple puts the money into banks which earn IOR at the Fed and the money “simply sits there.” The corporations are not withholding this money from the loanable funds market but rather, to the extent there is a problem, the loanable funds market does not know how to invest it at a sufficiently high ROR.

My arguments is that it can be a problem, and that recycling is not automatic, but in that case other factors must be in play and we should reinterpret the matter in terms of those other factors. Krugman may or may not agree but he doesn’t get to that point. Rather his critique is that I think recycling into AD is automatic. That is a “read fail,” and quite simply he would prefer to counter the argument (Keynes vs. Say) which fits into his prior template rather than deal with what was written.

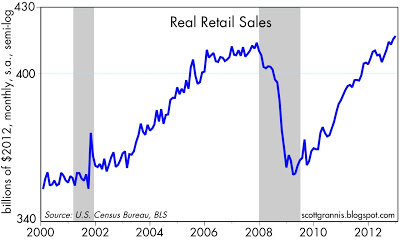

Dorman thinks there are few good investment opportunities because consumer spending is weak. In a somewhat condescending fashion, he suggests that somehow I cannot, when thinking about macroeconomics, keep investment and retail spending in my mind at the same time. He doesn’t mention that my original post considered retail spending explicitly — and with a picture — and argued that although there was a big hit to spending, the pattern of the hit and subsequent recovery for retail doesn’t appear to match the pattern of our investment problems. Again, he may disagree on the point, but he can’t even bring himself to mention that I cover it, instead preferring to claim I ignore it.

A new book on London

…between 1563 and 1665, on average every 25 years or so, London saw about a tenth or more of its population simply wiped out.

That is from the new and excellent book London: A Social and Cultural History, 1550-1750, by Robert O. Buchholz and Joseph P. Ward. This book was much fresher and original than I was expecting it to be and I can give it a strong recommendation. I, too, was thinking I didn’t want to read another tired book about the history of London.

Assorted links

Torture in a Just World

If the world is just, only the guilty are tortured. So believers in a just world are more likely to think that the people who are tortured are guilty. Perhaps especially so if they experience the torture closely and so feel a greater need to overcome cognitive dissonance. On the other hand, those farther away from the experience of torture may feel less need to justify it and they may be more likely to identify the tortured as victims. The theory of moral typecasting suggests that victims are also more likely to be seen as innocents (a la Jesus).

If the world is just, only the guilty are tortured. So believers in a just world are more likely to think that the people who are tortured are guilty. Perhaps especially so if they experience the torture closely and so feel a greater need to overcome cognitive dissonance. On the other hand, those farther away from the experience of torture may feel less need to justify it and they may be more likely to identify the tortured as victims. The theory of moral typecasting suggests that victims are also more likely to be seen as innocents (a la Jesus).

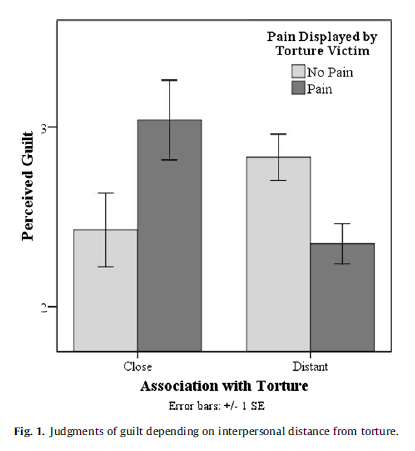

The theory is tested in a lab setting by Gray and Wegner. Experimental subjects are told that “Carol”, really a confederate, may have lied about a dice roll and that stress often encourages people to admit guilt. Subjects then listen to a torture session as Carol’s hand is plunged into a bucket of ice water for 80s. Subjects are then asked how likely is it that the torture victim was lying (1 to 5 with 5 being extremely likely). There are two intervention variables: 1) some of the subjects meet the torture victim before she is tortured, this is the close condition and some do not (distance condition) and 2) in some torture sessions the victim evinces pain (pain) and in others not (no pain). The key figure is shown below:

The most striking result is that in the close condition, the evincing of pain was associated with an increased judgment of guilt, consistent with torture causing cognitive dissonance which is relieved by a judgment of guilt (restoring the just world). But in the distance condition, the evincing of pain was associated with a decreased judgement of guilt, consistent with pain increasing the identification of the tortured as a victim and therefore innocent (a la moral typecasting).

The most striking result is that in the close condition, the evincing of pain was associated with an increased judgment of guilt, consistent with torture causing cognitive dissonance which is relieved by a judgment of guilt (restoring the just world). But in the distance condition, the evincing of pain was associated with a decreased judgement of guilt, consistent with pain increasing the identification of the tortured as a victim and therefore innocent (a la moral typecasting).

Closeness in the experiment was reasonably literal but may also be interpreted in terms of identification with the torturer. If the church is doing the torturing then the especially religious may be more likely to think the tortured are guilty. If the state is doing the torturing then the especially patriotic (close to their country) may be more likely to think that the tortured/killed/jailed/abused are guilty. That part is fairly obvious but note the second less obvious implication–the worse the victim is treated the more the religious/patriotic will believe the victim is guilty.

The theory has interesting lessons for entrepreneurs of social change. Suppose you want to change a policy such as prisoner abuse (e.g. Abu Ghraib) or no-knock police raids or the war on drugs or even tax policy. Convincing people that the abuse is grave may increase their belief that the victim is guilty. Instead, you want to do one of two things. Among the patriotic you may want to sell the problem as a minor problem that We Can Fix – making them feel good about both the we and the fixing. Or, you may want to create distance – The problem is bad and THEY are the cause. People in the North, for example, became more concerned about slavery once the US became us and them.

I think research in moral reasoning is important because understanding why good people do evil things is more important than understanding why evil people do evil things.

The future of ads on mobile devices?

The Chad2Win app was developed by a Barcelona-based company and while it was only launched last month it has already attracted close to 100,000 users. All these early adapters are being given a cent for each ad they look at and three times amount if the click on it.

Mind you it is not easy to reach the maximum monthly payment of €25 and to get there a user would have to click on more than 800 ads or nearly 30 different banners every single day.

Experts who have looked at the business model have suggested that most normal users are unlikely click enough ads to make themselves more than €10 a month.

Volkswagen, Panasonic and Spanish lender Caixabank have all agreed to advertise on the app which is only available in Spain. It does not appear to have wowed users and has a three star rating among android users while those who have signed up using their iPhones have decided it is only worth two-and-a-half stars out of a possible five.

Here is more. Overall I see the collapse in value for ads on mobile devices as a major problem facing mainstream media at the moment. No one wants to view an ad on a mobile device. Economic carnage will result.

Assorted links

1. Why the Anglo deal isn’t so great.

2. The booklogs of Zeynep Dilli.

3. Why KFC is finding it difficult to expand in Africa, and new link is here.

4. The best #Geithnerbooktitles.

5. Is Japanese recovery across 2000-2007 a puzzle? (My try at resolution would be to cite rising exports, and not think that “net exports” is the category which matters.)

Sentences to ponder

Are corporate profits a sinkhole for purchasing power?

That seems to be Krugman’s argument here, and here, excerpt:

So corporations are taking a much bigger slice of total income — and are showing little inclination either to redistribute that slice back to investors or to invest it in new equipment, software, etc.. Instead, they’re accumulating piles of cash.

I am confused by this argument. I would understand it (though not quite accept it) if corporations were stashing currency in the cupboard. Instead, it seems that large corporations invest the money as quickly as possible. It can be put in the bank and then lent out. It can purchase commercial paper, which boosts investment.

Maybe you are less impressed if say Apple buys T-Bills, but still the funds are recirculated quickly to other investors. This may not end in a dazzling burst of growth, but there is no unique problem associated with the first round of where the funds come from. If there is a problem, it is because no one sees especially attractive investment opportunities in great quantity. (To the extent there is a real desire to invest, the Coase theorem will get the money there.) That’s a problem at varying levels of corporate profits and some call it The Great Stagnation.

The same response holds if Apple puts the money into banks which earn IOR at the Fed and the money “simply sits there.” The corporations are not withholding this money from the loanable funds market but rather, to the extent there is a problem, the loanable funds market does not know how to invest it at a sufficiently high ROR.

If anything, large corporations are more likely to diversify out of the U.S. dollar, which could boost our exports a bit, a plus for a Keynesian or liquidity trap story.

When one looks at the components of aggregate demand, retail sales, after a large and obvious hit, seem to be recovering. They are up 4.7% from Dec. 2011 to Dec. 2012 (pdf). If that is what a sinkhole looks like, as I said I am puzzled:

Here is the story of business investment minus corporate profits and that series doesn’t impress me (Krugman seems to think it is doing OK). The trickier variable of net investment you will find here and that looks worse.

By the way, Fritz Machlup considered related arguments in his 1940 book.

The “austerity” of 2011-2012 in the United States

It turns out that much more of it was phony than many people had realized. From David Farenthold, this is from today’s Washington Post:

To sketch the bill’s biggest impacts, The Washington Post focused on the 16 largest individual cuts. Each, in theory, sliced at least $500 million from the federal budget. Together, they accounted for $26.1 billion, two-thirds of the total.

In four of those cases, the real-world impact was difficult to measure. The Department of Homeland Security officially declined to comment about a $557 million reduction. The Department of State, the Department of Agriculture and the Federal Emergency Management Agency — whose cuts totaled $1.9 billion — simply did not answer The Post’s questions despite repeated requests over the past month.

Among the other 12 cases, there were at least seven where the cuts caused only minimal real-world disruptions or none at all.

Often, this was made possible by a little act of Washington magic. Agencies got credit for killing what was, in reality, already dead.

Here is the article, and I did chuckle at the last paragraph.

*Engineers of Victory*

The author is Paul Kennedy and the subtitle is The Problem Solvers who Turned the Tide in the Second World War. This is an excellent look at the managerial and logistics side of the war. My main regret — not really a criticism — is that the central role of economists was not given more attention. Haven’t you wondered how it was possible that say the American role in the War was started and finished in less than five years’ time? These days it can take that long to design, approve, and build a freeway interchange.

Here is a good review of the book. Here is a useful NYT review.

My real fear about the UK productivity puzzle

…Britain’s economists are also puzzling over why the economy remains moribund even though more and more people are in work. There are still about half a million fewer people working as full-time employees than there were before the 2008 crash, but the number of people in some sort of employment has surpassed the previous peak. Economists think the rise in insecure temporary, self-employed and part-time work, while a testament to the British labour market’s flexibility, helps to explain why economic growth remains elusive.

That is from Sarah O’Connor’s excellent FT piece about working for Amazon in their warehouses.

Assorted links

1. Virgil Storr’s Understanding the Culture of Markets, and Les Miserables ROK Air Force Parody (video).

2. Buy a ten-minute phone call with Cedric Ceballos (MIE).

3. What are we learning from measuring basketball performance with data-tracking cameras?

5. 8,000 people still can speak Texas German (with audio sample).