Category: Books

The Inheritance of Gain

Kiran Desai won the Man Booker Prize in literature yesterday for the Inheritance of Loss, a novel about family bonds. Kiran’s mother Anita Desai is a three-time Booker nominee. See here for my previous post on this theme.

What I’ve been reading

1. Hidden Iran: Paradox and Power in the Islamic Republic, by Ray Takeyh. A good implicit "public choice" treatment of how the different factions in the Iranian government fit together. Surprisingly readable.

2. The United States of Arugula: How We Became a Gourmet Nation, by David Kamp. Terrible title, good content, awkward writing style, terrible font, little economics, still good for foodies but only for foodies.

3. The Road, by Cormac McCarthy. "Post-apocalyptic masterpiece." Fair enough, but is it better than The Dark Tower? I’m not sure, but even to pose that question is to favor Stephen King. Here is the NYT review.

4. The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood, by Rashid Khalidi. Some of the apologetics and omissions really bugged me. But as to why the Palestinians failed to construct their own state — before the creation of Israel — I learned a great deal.

5. Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses. His best novel. Fun from the outset, and you can test your knowledge of Bollywood and Islamic theology. Too famous as a political dispute, too little known as a book.

Public choice and the Nazis

On average, family members of German soldiers had 72.8 percent of peacetime household income at their disposal. That is nearly double what families of American (36.7) and British soldiers (38.1) received.

Götz Aly’s new and noteworthy Hitler’s Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State tells us how. The sad answer is that the Nazi regime lived off the resources it stole from conquered nations, forced labor, Jews, and refugees.

The magnitude of the theft was much larger than I had thought. In the fiscal year 1938-9, "Aryanization" increased government revenue by 9 percent. At its peak, Nazi theft was able to finance 70 percent of war revenues, noting that "war revenues" is a flow but the concept does not measure the real resource costs of fighting the war. See the book’s appendix for a response to some not totally unjustified criticisms of the author and his methods (the author’s claims seem to be correct as worded but the wording has narrower meaning than might strike an ordinary reader at first glance).

The good news, if you could call it that, is simply that the wartime Nazi regime was less stable than believed and it would have encountered very serious economic and military difficulties once the full plunder was extracted from abroad. If you are looking for a context where the long-run Laffer Curve holds, you’ll find it here.

What I’ve been reading

1. The Naked Brain: How the Emerging Neurosociety is Changing How We Live, Work, and Love, by Richard Restak. A good summary of a bunch of results I already knew, but a suitable introduction for most readers. It doesn’t cover neuroeconomics.

2. Light in August, by William Faulkner. I am rereading this, wondering whether I should use it for my Law and Literature class in the spring. My memory was that this is the "easy" classic Faulkner but the text is tricker than I had remembered. Not quite as good as As I Lay Dying or Absalom, Absalom.

3. Matthew Kahn, Green Cities: Urban Growth and the Environment. From Brookings, a good and balanced treatment of the intersection between environmental and urban economics. Here is Matt’s blog.

4. Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion. I’m still at p = .05, if only because I fear such a heavy reliance on the anthropic principle. This book didn’t sway me one way or the other. And while I am not religious myself, I am suspicious of anti-religious tracts which do not recognize great profundity in the Bible. Furthermore, as Dawkins recognizes, civilization requires strong loyalties to abstract principles; I’m still waiting to see a list of the relevant contenders to choose the best. Here is Dawkins speaking.

5. Michael Lewis, The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game. I loved Liar’s Poker and Moneyball but this one did not grab me at all. I stopped. Perhaps the reader needs to love football. Here is a radio interview with the author. Here is his NYT article.

We are Iran

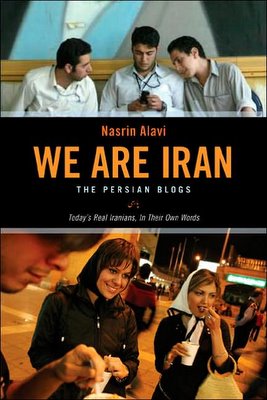

Here is the UK cover for a book on Iranian bloggers:

Your screen is OK, the image has lots of white space. Here is the US cover of the same book:

Are U.S. covers in general more literal? Here is the the source; the fascinating blog is devoted to discussing book covers. Here is the UK-US comparison for David Mitchell’s excellent Cloud Atlas. Here is the Turkish cover of Freakonomics. Here is an iPod ad from the Czech Republic.

Live as a conservative?

- Charlie Daniels Band—Essential Super Hits of Charlie Daniels Band

- Clint Black—Greatest Hits II

- Craig Morgan—Craig Morgan

- Daryl Worley—Have You Forgotten?

- Kid Rock—Devil Without a Cause

- Lee Greenwood—American Patriot

- Michael W. Smith—Healing Rain

- Toby Keith—Unleashed

Movies:

The link is from Jason Kottke.

Moscow 1941

When the storm broke, people turned to Tolstoy: "During the war," wrote the critic Lidia Ginzburg, "people devoured War and Peace as a way of measuring their own behavior (about Tolstoy they had no doubt: his response to life was wholly adequate). The reader would say to himself: Well then, so what I am feeling is right: that’s just how it should be." War and Peace was the only book the writer Vasili Grossman had time to read while he was a frontline correspondent, and he read it twice. It was broadcast on Moscow Radio, complete, over thirty episodes.

That is from new and noteworthy Moscow 1941: A City and its People at War, by Rodric Braithwaite, recommended.

Europe at the Crossroads

In face of these issues, it is difficult to understand why half the EU budget is still devoted to subsidizing agriculture…

That is from Europe at the Crossroads, by Guillermo de la Dehesa. Contrary to what the above excerpt may indicate to some, this is not a "Europe-bashing" book. It is perhaps the best short, comprehensive overview of the European economies, their strengths, and their problems. Matt Yglesias makes good points about Scandinavia and competitiveness, but I cannot agree that the main problems of France and Germany are macroeconomic in nature.

Henry Farrell reviews my new book

He is very kind. Why don’t I excerpt the part that praises me most?:

There are two, quite different libertarian styles of writing about culture that I enjoy. One is the pop-culture variety, which uses libertarian precepts as the framework for a certain kind of flip, contrarian analysis. This can be quite entertaining, but it usually doesn’t bear up well to close examination. Libertarian nostrums all too frequently substitute for actual thought (granted, much leftist opinionating on culture has similar problems). The second style is that of Tyler Cowen. Cowen writes in an entertaining and straightforward manner. He’s enthusiastic and knowledgeable about both high and low culture. But the fun of his arguments is that they’re serious, interesting, and properly thought through. If they’re hard to fit into conventional frameworks of debate, they aren’t self-consciously contrarian either. Instead, they lead in their own directions, and Cowen isn’t afraid to follow them, even if they lead to unexpected destinations.

If you haven’t already, you can buy the Good and Plenty: The Creative Successes of American Arts Funding here.

The Conquest of Nature

I had not realized how man-made and engineered the Rhine was, and how early this occurred:

This was the largest civil engineering project that had ever been undertaken in Germany. The Rhine between Basel and Worms was shortened from 220 to 170 miles, almost a quarter of its length. Dozens of cuts were made, more than twenty-two hundred islands removed. Along the stretch between Basel and Strasbourg alone, well over a billion square yards of island or peninsula were excavated and 160 miles of main dikes constructed containing 6.5 million cubic yards of material. During the 1860s the number of fascines being used was running at up to 800,000 a year.

That is from David Blackburn’s The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany. This history of water engineering is not a book for all of you, but if you think you might like it, you will.

Addendum: Elsewhere on the new book front, Niall Ferguson is a splendid author, but his new The War of the World doesn’t add much.

Freakonomics 2.0

1. Dubner describes the forthcoming revised edition of the book.

2. Commentary on the recent and apparently pro-market Swedish elections.

3. The World Chess championship match starts Saturday in Kalmykia, Europe’s only Buddhist republic. Here is one very good analysis of the players.

4. Hal Varian on the county-specific theory of American income inequality; the high-tech boom seems to play a big role.

The Great Risk Shift

That is the new book by Jacob Hacker which should, and probably will, have a big impact on national debate. The main argument is that American incomes have been growing steadily riskier. (Here is a related article by Hacker, and here is U.S. Census data.) A few points:

1. The most convincing of the graphs is the one which shows "Americans’ Chance of a 50 Percent or Greater Income Drop." In 1970 this risk was at about 7 percent; it has been rising upward and now stands at a little over 16 percent. I would be happier if the relatively wealthy were excluded from this diagram, although I doubt if those people are driving the results.

2. Chapter two blames the new ethic of personal responsibility, and associated policy changes, for increased income volatility. Data suddenly are absent, and I cannot help but note that most forms of domestic government spending, including social insurance programs, have grown steadily. Nor can Clinton welfare reform be blamed here. This is the weakest chapter in the book.

3. Chapter three on risky jobs is not strong on data compared to the contrasting results found in this working paper and also the writings of John Haltiwanger and others.

4. Chapter four on families discusses divorce, but we do not learn how much of the growth in income volatility stems from family splits. The author does point out that the divorce rate peaked in the 1980s yet income volatility continues to climb. The relative importance of divorce is the one question this book should have answered, and could have answered, but didn’t answer.

While divorce raises income risk, it may lower utility risk, especially for women.

I am also dismayed that the author cites a U.S. savings rate of zero, overstates the risk of housing investments (if all homes exogenously became very cheap even homeowners are better off), and cites the dubious book The Two-Income Trap. There is not enough discussion of asset values and new possibilities for consumption smoothing. How volatile are the data on consumption?

5. Chapter five on risky retirement focuses on pensions and nails it.

6. I don’t buy chapter six on "Risky Health Care." The real risk of dying too young, or being severely crippled too young, has never been lower. Again, risk is more than just financial risk.

The bottom line: We do need pension reform. Otherwise Hacker needs to separate out the importance of divorce and better distinguish financial risk from utility risk. If people are spending more money to lower their utility risk — most of all spending on divorce and healh care — the results are suddenly less troubling. I am far from certain this is the relevant scenario, but Hacker does not establish, or even try to establish, the contrary.

Addendum: Arnold Kling argues that, in a risky world, we should strengthen incentives to save.

Cass Sunstein, Tyler Cowen, and Robin Hanson

When should we consume culture in small, sequential bits?

I almost always read novels in bits. That is, I put the book down for a few times before finishing it.

I rarely watch movies in bits. That just seems wrong. But, assuming we are watching on DVD, why? Why do pauses ruin a movie but not a book? I can think of a few hypotheses:

1. Movies manipulate our neurophysiology over a two-hour time horizon. If we restart in the middle after a two-day pause, we are not worked up in the right manner.

2. Most books are longer than most movies, but there is otherwise no good reason for the difference in our consumption pattern.

3. We like the idea that we are "reading Camus," and thus we wish to stretch it out. Few people get comparable status or feel-good values from watching movies and thus there is no need to prolong that experience.

4. We don’t actually like reading enough to keep on paying attention for so many hours in a row.

The ever-wise Natasha notes that we are mostly likely to read action novels — such as The da Vinci Code

— straight through without pause. But action movies are the easiest to

watch in bits. Ever try just a half hour of Jackie Chan? Wonderful. But breaking up a good drama is criminal.

Your thoughts?

Luxury goods

…very early on Arnie called me into his office for some reason, and I had an interview with him. He told me that I was a luxury good and that I didn’t do business. I did theoretical economics and it wasn’t something that business schools could really support, and he did it in a very obnoxious way that really pissed me off. And I said "—- you, Arnie."

That is David Cass, from William Barnett and Paul Samuelson’s new book Inside the Economist’s Mind: Conversations with Eminent Economists. Their version of the quotation adds a "f" but not the three further letters.

Mostly this book bored me, but only because I know so much about the subjects already. If you know less about them than I do, but know enough about them that you care, you might find it fascinating.