Category: Education

Very good sentences

Perhaps the “something nicer” which should replace capitalism is a more nuanced – and more accurate – account of capitalism itself.

That is from John Kay, here is more.

College has been oversold

Here, drawn from my new e-book, Launching the Innovation Renaissance (published by TED) is part of a section on college education. (See also the op-ed in IBD)

Educated people have higher wages and lower unemployment rates than the less educated so why are college students at Occupy Wall Street protests around the country demanding forgiveness for crushing student debt? The sluggish economy is tough on everyone but the students are also learning a hard lesson, going to college is not enough. You also have to study the right subjects. And American students are not studying the fields with the greatest economic potential.

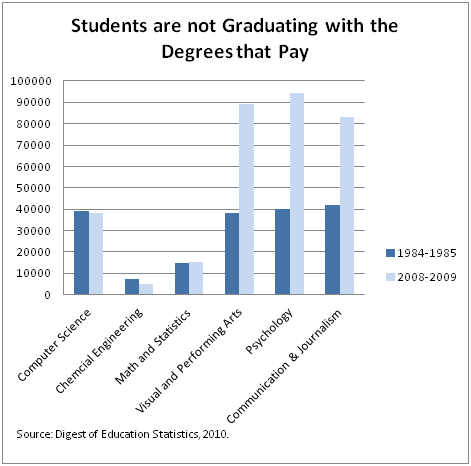

Over the past 25 years the total number of students in college has increased by about 50 percent. But the number of students graduating with degrees in science, technology, engineering and math (the so-called STEM fields) has remained more or less constant. Moreover, many of today’s STEM graduates are foreign born and are taking their knowledge and skills back to their native countries.

Consider computer technology. In 2009 the U.S. graduated 37,994 students with bachelor’s degrees in computer and information science. This is not bad, but we graduated more students with computer science degrees 25 years ago! The story is the same in other technology fields such as chemical engineering, math and statistics. Few fields have changed as much in recent years as microbiology, but in 2009 we graduated just 2,480 students with bachelor’s degrees in microbiology — about the same number as 25 years ago. Who will solve the problem of antibiotic resistance?

If students aren’t studying science, technology, engineering and math, what are they studying?

In 2009 the U.S. graduated 89,140 students in the visual and performing arts, more than in computer science, math and chemical engineering combined and more than double the number of visual and performing arts graduates in 1985.

The chart at right shows the number of bachelor’s degrees in various fields today and 25 years ago. STEM fields are flat (declining for natives) while the visual and performing arts, psychology, and communication and journalism (!) are way up.

There is nothing wrong with the arts, psychology and journalism, but graduates in these fields have lower wages and are less likely to find work in their fields than graduates in science and math. Moreover, more than half of all humanities graduates end up in jobs that don’t require college degrees and these graduates don’t get a big college bonus.

Most importantly, graduates in the arts, psychology and journalism are less likely to create the kinds of innovations that drive economic growth. Economic growth is not a magic totem to which all else must bow, but it is one of the main reasons we subsidize higher education.

The potential wage gains for college graduates go to the graduates — that’s reason enough for students to pursue a college education. We add subsidies to the mix, however, because we believe that education has positive spillover benefits that flow to society. One of the biggest of these benefits is the increase in innovation that highly educated workers theoretically bring to the economy.

As a result, an argument can be made for subsidizing students in fields with potentially large spillovers, such as microbiology, chemical engineering, nuclear physics and computer science. There is little justification for subsidizing sociology, dance and English majors.

College has been oversold. It has been oversold to students who end up dropping out or graduating with degrees that don’t help them very much in the job market. It also has been oversold to the taxpayers, who foot the bill for these subsidies.

Signaling or human capital?

Is there any way to sustain the current revenue model of higher ed? How about firefighters? You can read this story as illustrating human capital theories of education, signaling theories, or both:

“We still put out fires with water,” said Deason, who is also a lieutenant and paramedic at a fire department in Homewood, Ala. But fire companies these days “need people who are a little more advanced with their education.”

As a result, college degrees that are not fire-related can also help. Deason and Crowther said fire departments increasingly want career employees who have strong critical thinking skills, and who can write grants or do public speaking, particularly as they progress to leadership roles.

Two other drivers of the growing higher education demand among firefighters are the recession and colleges’ online offerings. Purchasing and budget decisions are more important than ever, as most municipalities have tight finances. And financial and technical know-how helps when considering big expenses, like the $675,000 fire engine Deason said his company recently bought.

… In the future, he said advanced degrees will probably be an “absolute requirement” for most chief positions.

Why the current revenue model of higher education is in trouble

The picture for females is also not pleasant, all from the excellent Michael Mandel. Those are simple facts, denied by some.

Non-college grads also have seen declining wages, and so one can look at the “finish college vs. finish high school only” margin and conclude that the return to higher education is robust. Another approach is to look at the “finish college and get on a real career track” vs. “finish college and hang out” margin and conclude the sector is in trouble, which indeed is the case. Don’t get stuck looking at the old margins only, the new and powerful margin, I am sorry to say, is relative to unemployment or extreme underemployment. The status and avoid-shame returns are high enough to keep a lot of people going to college, at current prices, but the falling real wages for graduates aren’t going to sustain an enormous amount of extra sectoral growth, including on the price side. Nor do I expect the preceding orgy of student debt to repeated, at that level, anytime soon.

The culture that is (was) Germany

There are still some students on university campuses who reminisce about the old days. One of those so-called “eternal students” can be found at Christian Albrecht University in the northern city of Kiel. He registered as a student in medicine when Konrad Adenauer was still chancellor and the Berlin Wall hadn’t even been planned yet. Even though he is in his 108th semester, the university does not have the power to throw him out. As one university spokesman explains, the rules for majors that require students to take a state examination, such as medicine, do not contain provisions for ejecting long-term students.

Yet those days are coming to an end, here is much more.

*Grad School Rulz*

Let’s turn the mike over to Bryan Caplan:

Fabio Rojas’ pearls of wisdom for grad students are now available as a concise, information-packed $2 e-book. Definitely worth the money if you have any noticeable interest in grad school.

I have yet to read this book, but Alex and I both love Fabio, who has been a frequent MR guest-blogger in the past. He also has excellent taste in jazz.

From yesterday’s New York Times

They are experimenting with different models of human behavior, here is from Modern Love:

At first his behavior was endearing. He constantly gave me attention, lavishing me with compliments, calls and sometimes gifts. But one morning when I slid out of bed from next to him, things felt different. All his wooing suddenly repelled me.

I crawled back in and tried my best to pretend things were O.K. He showered and dressed. I clenched my teeth when it was time to kiss goodbye, then shut the door behind him, sighed and wondered if he had any idea.

We learn from this same column that butterflies can see with their genitals. And from the NYT Sunday Magazine, here is a Death Row love story:

“I knew you were going to say your favorite color is blue,” he wrote. “It belongs to you. My favorite colors are black and crimson. I love deep, dark red things made of red velvet.”

Overeducation in the UK

Chevalier and Lindley have a new paper:

During the early Nineties the proportion of UK graduates doubled over a very short period of time. This paper investigates the effect of the expansion on early labour market attainment, focusing on over-education. We define over-education by combining occupation codes and a self-reported measure for the appropriateness of the match between qualification and the job. We therefore define three groups of graduates: matched, apparently over-educated and genuinely over-educated; to compare pre- and post-expansion cohorts of graduates. We find the proportion of over-educated graduates has doubled, even though over-education wage penalties have remained stable. This suggests that the labour market accommodated most of the large expansion of university graduates. Apparently over-educated graduates are mostly indistinguishable from matched graduates, while genuinely over-educated graduates principally lack non-academic skills such as management and leadership. Additionally, genuine over-education increases unemployment by three months but has no impact of the number of jobs held. Individual unobserved heterogeneity differs between the three groups of graduates but controlling for it, does not alter these conclusions.

For the pointer I thank Alan Mattich, a loyal MR reader.

A simple approach to macroeconomic theorizing

I can’t say it is guaranteed to work, but I give it a high “p”:

1. Take the macroeconomic theory you hold and stick it into a box.

2. Take the major competing macroeconomic theory, the one you dislike, but taking care that you have selected an approach endorsed by high-IQ researchers. If you dislike them too, that does not disqualify the theory, quite the contrary.

3. Stick theory #2 into the same box.

4. Average the two theories.

5. Pull the average out of the box, and call it your new theory.

How many times should you apply this method? At least once I say.

I am indebted to Hal Varian for a useful conversation on related topics.

North Korean photos

Sorry for the bad link from yesterday, find them here. I thank Yana for the pointer.

The rise of the generalist

I don’t know if I’ve heard anyone say this and I am not quite sure what I think about it myself, but one way to view the economy in the Information Age is that the returns to specialization are falling.

So, those who like such things can go all the way back to Adam Smiths pin factory and think about all the tasks involved in making pins and how each person could become more suited to that task and learn the ins and outs of it.

However, in the information age I can in many cases write a program to repeatedly perform each of these tasks and record ever single step that it makes for later review by me. The individualized skill and knowledge is not so important because it can all be dumped into a database.

What really matters is someone who gets pins. Not the various steps involved in making pins but the concept of the whole pin. What makes a good pin a good pin. How do pins fit into the entire global market. What the next big thing in pins.

This individual will be able to outline a pin vision that she or just a few programmers can easily implement. One could say this is the story of Facebook or Twitter. Really good ideas and just a few people needed to implement them.

However, as IT progress and machines can do more things it could be the story of the economy generally.

In contrast to The Great Stagnation, I would call this The Rise of Generalist or perhaps to be consistent The Great Generalization.

Even if you stop and think for a minute about all of the things that your computer or now even your phone can do, are you now wielding the most generalized tool ever conceived?

I would add in turn that the Generalist boosts the reach of the Specialist, as the Generalist relies on many specialists to supply inputs for his or her outputs. It may be the “tweeners” in the middle who lose income and influence, and that the extreme generalists and specialists will prosper, intellectually and otherwise.

The world’s funniest analogies

From this longer list (funny throughout), presented by Bill Gross and (possibly) derived from student writings, Jason Kottke provides his favorites:

Her vocabulary was as bad as, like, whatever.

From the attic came an unearthly howl. The whole scene had an eerie, surreal quality, like when you’re on vacation in another city and Jeopardy comes on at 7:00 p.m. instead of 7:30.

He was as tall as a six-foot, three-inch tree.

John and Mary had never met. They were like two hummingbirds who had also never met.

His comment:

That first one…I can’t decide if it’s bad or the best analogy ever.

I liked this one:

He was as lame as a duck. Not the metaphorical lame duck, either, but a

real duck that was actually lame, maybe from stepping on a land mine or

something.

From the comments, on local employment of teachers

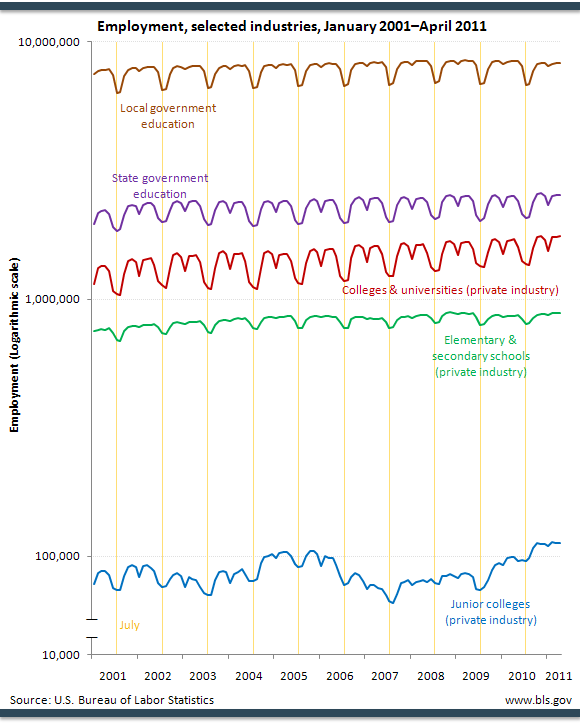

The scaling in the chart makes a big difference. Here’s the data behind the chart, which can by found by following a link on the site that Tyler links to: http://1.usa.gov/oOQXeO. For the local government column only and April figures. (May would be better but the series runs out at April 2011.) April 2011 was at 8.3 million, about 160K less than the peak two Aprils earlier. That’s about 1.5% difference.

That is from RZO, the link and context is here. In the same comment thread, Frank Howland notes that:

K-12 enrollments fell by 0.85% from 2007 to 2009

That’s not exactly the same years and the data go only to 2009 but could it be a general trend across 2009-2011? Given that context, there is still some decline in per capita local teacher employment. Note this is a sector where there is a growing realization that quite a few of the workers should, for non-cyclical reasons, be fired anyway.

Addendum: Karl Smith has a useful graph with seasonal adjustment, coming up with somewhat different numbers.

How many unemployed teachers are there?

This bit from Bruce Yandle challenges the conventional wisdom:

As to hiring teachers, total employment in local government education is already up by one million workers since August 2010. Teacher employment in state government nationwide is up 300,000 workers. The unemployment rate in education and health services at 6.3% is one of the nation’s lowest unemployment rates. While the president implied that teachers were being cut from payrolls at a heavy pace, the data say otherwise. The president’s efforts are seen as misguided if the goal is to ease some of the pain in high unemployment sectors.

Here is another source:

As Figure 1 shows, state government education employment is up by 2.1 percent since the start of the recession while all other state government employment is down 1.9 percent — a substantially larger decline than in other parts of the state-local sector. State government non-education employment began falling less than a year into the recession, and fell below its pre-recession level about a year and a half after the start of the recession.

Do you wish to see more, including on local government education employment?

This BLS graph (look under “And which industries show declining employment over the summer?”) shows a strong seasonal trend which may confound some month-specific citations, but still the number seems to be back to where it had been in earlier years (admittedly the scaling and visuals are not what I would wish for) and more importantly it is hard to spot much effect of the recession at all:

So what exactly is the case here for stimulus of this sector? Is this really a sector to target? I would gladly see and consider alternate numbers and interpretations, but so far I file this under: “Yet another example of something the press should have reported about a President’s speech but didn’t.” Once again, it is the disaggregated demand which matters.

Turnitin: Arming both sides in the Plagiarism War

The internet has made plagiarism much easier and by most accounts plagiarism is increasing rapidly. As a result, over a million instructors now use services like Turnitin, a plagiarism detector that compares submitted manuscripts against a large database of material, including previously submitted manuscripts. What is less well appreciated is that Turnitin also sells its services to students. In fact, students whose professors use Turnitin are encouraged to pre-submit their work to Writecheck which will analyze and “verify” for the students that their paper has “properly quoted, summarized or paraphrased” previous work and it will also relieve students from “worrying that their paper will be recycled without their knowledge.” Uh huh.

In other words, WriteCheck will tell students if their essays will pass Turnitin! David Harrington summarizes nicely:

Turnitin is playing both sides of the fence, helping instructors identify plagiarists while helping plagiarists avoid detection. It is akin to selling security systems to stores while allowing shoplifters to test whether putting tagged goods into bags lined with aluminum thwart the detectors.