Category: History

*Keep from All Thoughtful Men: How U.S. Economists Won World War II*

That is a new book out by Jim Lacey. Here is one good review by Christopher Tassava:

…Lacey (a retired U.S. Army officer and current writer on defense matters) describes the bureaucratic fights between civilian experts and military staff over the extent and speed to which the American economy — hardly firing on all cylinders as war began in Europe — could be reoriented to produce the munitions necessary for a serious military effort. At the center of Lacey’s story are three economists who, he shows, had far-sighted views of the true capacity of the American economy: the reasonably well known Simon Kuznets and two nearly forgotten figures, Robert Nathan and Stacy May.

Lacey capably uses archival and secondary sources to show that these three men, along with a small group of other civilians inside the federal bureaucracy, were able to use social-scientific methods, including, crucially, statistical techniques, to assess how large the U.S economy could grow, how quickly that growth could occur, and how much war materiel the economy could produce for use by the U.S. and Allied militaries. Lacey persuasively shows that Kuznets, Nathan, and May were able to forecast in late 1942, before the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor, that June 1944 would be the moment at which the American “arsenal of democracy” would be able to produce sufficient materiel to launch a substantial invasion of Europe.

The words English has taken from India

Another author who has drawn inspiration from the dictionary is Tom Stoppard. In his play Indian Ink, two characters compete to use as many Hobson-Jobson words as possible:

- Flora: “While having tiffin on the veranda of my bungalow I spilled kedgeree on my dungarees and had to go to the gymkhana in my pyjamas looking like a coolie.”

- Nirad: “I was buying chutney in the bazaar when a thug who had escaped from the chokey ran amok and killed a box-wallah for his loot, creating a hullabaloo and landing himself in the mulligatawny.”

Here is more, hat tip goes to The Browser. They also refer us to this long interview with philosopher Thomas Scanlon, and Ed Glaeser on what American can learn from Australia.

Reminiscences of Miles Kimball, and others

Miles and I were in the same entering class in Harvard. Miles and Abhijit Banerjee were for economic theory the sharpest students in the group and it must have been an absolute terror to teach them. Both were gentlemanly in the extreme, but if a mistake or ambiguity were on the board, or in a paper, you could be sure they would find it and point it out. I recall Abhijit answering a question on the macro final exam and showing that what he thought would be the supposed Harvard faculty member answer was in fact wrong, in addition to solving for the right answer, finding a few other possible equilibria, and acing the rest of the exam in but a few hours’ time. Steve Kaplan, from the same class, later became known as an empirical economist but his theoretical acumen was remarkably good. Those three dominated a lot of the discussions. Mathias Dewatripont was also no slouch in theory though temperamentally quieter. Alan Krueger, in his third year, obtained the reputation of having the best eye for an important empirical paper and how to execute it; he learned the most from Larry Summers. Nouriel Roubini was generally quiet, though he looked all-knowing and at times slightly jaded.

Brad DeLong was a few years older. He was thought of as the slightly right-wing guy (compared to his peers he was) who read a lot of unusual history of economic thought, including Adam Ferguson. He and his girlfriend (now wife) were inseparable and always affectionate.

Miles struck me as a mind in perpetual motion, in the best sense of that phrase. I was not surprised, in 1984, when I heard about his linguistics Master’s thesis, which includes a learned and original discussion of Charles Peirce. Miles is also a cousin of Mitt Romney, and he will soon blog “Will Mitt’s Mormonism Make Him a Supply-Side Liberal?”. I wonder what he makes of us all.

Here are his early tweets.

One feature about his blog which is refreshing is that he is neither a libertarian nor a progressive, though he incorporates ideas from both approaches. My RSS feed is mostly libertarians and progressives, but that is part of the strange selection mechanism of the blogosphere, not a reflection of the economics profession.

Again, Miles’s blog is here and Miles on Twitter is here. Most of all, he seems to be a great dad, or at least his daughter thinks so. She too is studying at Harvard, for an MBA. Here is her project Expert Novice, “Every month or so, I write a letter about what I’ve learned lately.”

*Rome: An Empire’s Story*

That is the new book by Greg Woolf. Could it now be the best single-volume introduction to the history of ancient Rome? It is conceptual yet avoids the pitfalls of overgeneralizing, a difficult balance to strike. It also has a superb (useful rather than exhaustive) bibliography. A good measure of books such as this is whether they induce you to read or order other books on the same topic and this one did.

A sure thing to make my “Best Books of 2012” list.

Paul Krugman on contractionary devaluation

This is from the 1970s, and with Lance Taylor:

The presumption that devaluation is expansionary is not supported by firm empirical evidence. Why, then, is it so widely accepted? Leftists have been known to suggest class bias — as we will argue later, devaluation does typically redistribute income from wages to profits — but this is too glib. We believe, instead, that the orthodox view of devaluation derives much of its strength from the persuasive power of the simple, elegant models in which it is presented. Since skeptics have mostly relied on Journalism or at best partial equilibrium analysis, it is not surprising that theoretical discussion is dominated by the belief that devaluation has an expansionary effect.

As just hinted, neglecting the contractionary impacts of devaluation amounts to ignoring income effects, especially those transferring real purchasing power toward economic actors with high marginal propensities to save. By redirecting income to high savers, devaluation can create an excess of saving over planned investment ex_ ante , and reductions in real output and imports ex_ post .

…Casual empiricism suggests that all three circumstances prevail in many countries, especially the less developed ones. In these

countries a deflationary impact from devaluation is more than a remote possibility; it is close to a presumption. The purpose of this paper is to show in a formal model how devaluation can cause an economic contraction. The results will come as no surprise to those concerned with policy in the underdeveloped world.

There is nothing wrong with changing your mind, as indeed I have myself on numerous issues. The point is that most macro questions are not cut and dried, and opposing viewpoints are rarely stupid. I also note a general tendency that, when critics attack other people, they are often attacking views they once held themselves. I leave it to Adam Phillips and Darian Leader to tell us what that means.

The document you will find here. For the pointer I thank Jay S.

The culture that was Japan

“It was a generation,” Kuroda said through an interpreter, “when [baseball] coaches believed you should not drink water.”

Born in 1975, Kuroda is one of the last of a cohort of Japanese players who grew up in a culture in which staggeringly long work days and severe punishment were normal, and in which older players could haze younger ones with impunity.

Summer practices in the heat and humidity of Osaka lasted from 6 a.m. until after 9 p.m. Kuroda was hit with bats and forced to kneel barelegged on hot pavement for hours.

“Many players would faint in practice,” Kuroda said with the assistance of his interpreter, Kenji Nimura. “I did go to the river and drink. It was not the cleanest river, either. I would like to believe it was clean, but it was not a beautiful river.

“In order to play,” he added, “you had to survive. We were trained to build an immune system so that we could survive and play.”

Here is more, hat tip to Hugo. As I often say, I am a utility optimist and a revenue pessimist, for Japan most of all.

*Face Value: The Entwined Histories of Money & Race in America*

That is the new book from Michael O’Malley, a colleague of mine in the history department. Here is one of the book’s most controversial passages:

It should come as no surprise, then, to find that right-wing libertarians and proponents of the free market often tend to favor genetic accounts of identity. The heroic individualism many libertarians imagine requires a self freed from all social constraints, but at the same time founded in nature — in natural rights and natural talents. The libertarians account of individualism rests on imagining a person free of social and political power. Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead ends with her visionary ego-driven architect standing above the city: “there was only the ocean and the sky and the figure of Howard Roark.” That is, nothing but nature and the heroic individual, standing above society: an intrinsic self entirely in possession of itself. In this sense libertarianism embraces not freedom but a kind of genetic determinism, in which “merit” derives not from social whims but from intrinsic qualities and, again in which all hierarchies are “natural.” Rand’s clunky Atlas Shrugged imagines a world in which all the creative and productive people have fled to a secret location, leaving the rest of us, “looters” and “parasites,” flailing helplessly like ants bereft of the queen. Right-wing libertarianism in this way again bears a close relationship to its nineteenth-century antecedent, social Darwinism. It stresses freedom, but also imagines nature as a set of stable confines and success as the proper reward for genetic superiority.

The book also offers an interesting discussion of the role of the gold standard in 19th century thought. There are also sections which Brad DeLong would quote at length.

I was surprised to just learn that O’Malley has an interest in Eddie Lang. I didn’t know anyone else still thought about Eddie Lang, there is YouTube here.

My 28-minute talk on black swans

What would we do if it turned out there were more black swans than we had thought? What should we do?

You can view the talk here, given at the Legatum Institute in London not too long ago.

New books in my pile

Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class–Revisited: 10th Anniversary Edition–Revised and Expanded.

There is also The Kipper und Wipper Inflation, 1619-23, An Economic History with Contemporary German Broadsheets, by Martha White Paas, John Roger Paas, and translations by George Schoolfield. The origins of German monetary thought turn out to be more important than might have been expected…

Is September the cruelest month?

That is from Greg Ip, reporting the work of Luc Laeven and Fabian Valencia (pdf), feel free to regard it as a spurious correlation!

South Korea fact of the day

Although inflation in the late 1970s was below the 1974-1975 level, it was high by post-Korean War standards. It was up from 16% in 1977 to 22% in 1978 and 1979. The average rate of inflation in Korea in the period 1962-1969 was 17.3%. In the period 1970-1979 it was 19.3%.

You will note that South Korea, during those years and subsequently, was one of the greatest growth marvels in all of human history.

The point is not that we should aim for such high rates of inflation today, rather that if growth is strong an economy can stomach more inflation than you might think.

That quotation is from Alice Amsden, Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization.

New books in my pile

Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class–Revisited: 10th Anniversary Edition–Revised and Expanded.

There is also The Kipper und Wipper Inflation, 1619-23, An Economic History with Contemporary German Broadsheets, by Martha White Paas, John Roger Paas, and translations by George Schoolfield. The origins of German monetary thought turn out to be more important than might have been expected…

When are ‘secure’ property rights bad for growth?

Greg Clark has argued that private property was secure in medieval England on the basis that

‘Medieval farmland was an asset with little price risk. This implies few periods of disruption and uncertainty within the economy, for such disruption typically leaves its mark on the prices of such assets as land and housing’ (p 158).

And on the basis of low taxes in medieval England, he goes on to claim that:

‘if we were to score medieval England using the criteria typically applied by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to evaluate the strength of economic incentives, it would rank much higher than all modern high-income economies—including modern England’ (p 147) . . . If incentives are the key to growth, then some preindustrial societies like England had better incentives than modern high-income economies. And incentives may be much less important to explaining the level of output in economies than the Smithian vision assumes’ (p 151).

Even if most would not go so far as Clark, many economic historians now argue that property rights were secure in late medieval and early modern England, and that some property rights actually became less secure after the Glorious Revolution. Drawing on the work of Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Dan Bogart, and Gary Richardson, Bob Allen summarizes these findings as follows:

‘Growth was also promoted by Parliament’s power to take people’s property against their wishes. This was not possible in France. Indeed, one could argue that France suffered because property was too secure: profitable irrigation projects were not undertaken in Provence because France had no counterpart to the private acts of Parliament that overrode property owners opposed to the enclosure of their land or the construction of canals or turnpikes across it’

See here, here and here for links to the academic work that underpins these claims. For the sake of argument let us agree that they are correct. What does this finding mean?

It does not mean that insecure property rights are good for growth.

It does mean that feudalism was bad for growth.

The property rights that Clark and others describe as being secure in medieval Europe were feudal property rights. Feudalism structured ownership rights in such a way as to channel rents to the king and the military elite. Feudal property rights were designed to maintain concentrated holdings of land, large enough to support feudal armies. Feudal laws limited land sales that would break-up large estates and bundled together rights over land with rights over individuals.

In a market economy, where rights are clearly defined, assets will be allocated to their highest-value user so long as transaction costs are not too high. In this type of environment protecting asset holders from expropriation provides the best incentives for investment and growth. But this was not true of the medieval world.

What Bogart and Richardson establish is that these feudal rights impeded efficient land use in England and made it difficult to organize the provision of public goods. They show how Parliament in the 18th century was able to rewrite and override existing property rights. Their work suggests that given the initial allocation of rights and the extremely high transactions costs associated with feudal land law, a reconfiguration of property rights was necessary for economic growth to begin.

Taxes and the Onset of Economic Growth

In a recent book Besley and Persson 2011 argue that fiscal capacity is strongly correlated with economic performance across countries (see also here and here). They cite important historical work by Mark Dincecco who has shown that across Europe, between 1650 and 1900, higher taxes were associated with both limited government and economic growth (see here). The following graph is from Dincecco (2011) which contains similar figures for other European countries.

This finding can be interpreted in many ways. The state capacity literature emphasizes the idea that governments need an adequate tax system in order to provide the institutional preconditions necessary for economic growth.

Perhaps there is an alternative explanation for the historical correlation between higher taxes and economic growth. This has to do with selection bias in historical data sets. Modern states did not emerge out of nowhere. They replaced pre-existing local systems of taxation, patronage, and rent seeking. We have a relatively large amount of information about what strong, central, governments were doing and what taxes they were collecting. However, we do not have much information about local regulations or tax systems that existed before the rise of modern states because these local institutions were subsumed or destroyed by the state-building process. There is plenty of evidence that these local systems imposed large deadweight losses, although it is difficult to put together a database measuring how large these distortions were (see this paper by Raphael Frank, Noel Johnson, and John Nye or just read about the Gabelle; also see Nye (1997) for this point).

The implication of this argument is that an increase in the measured size of central government need not have been associated with an increase in the total burden of government. Rather the total deadweight loss of all regulations and taxes could have gone down in the 18th and 19th centuries, even as the tax rates imposed by the central state went up.

(Note: the increase in per capita revenues in England depicted in the figure is largely driven by higher rates of taxation (notably the excise) and more effective tax collection and not by Laffer curve effects (although the growth of a market economy during the 18th century did make it easier for the state to collect taxes).

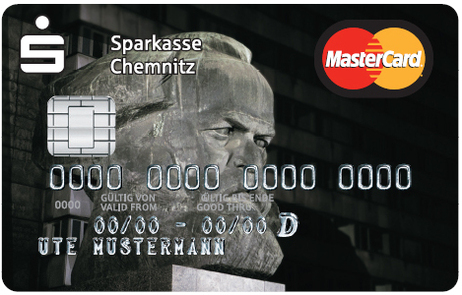

Markets in Everything: The Karl Marx Credit Card

The Karl Marx credit card now available in Eastern Germany for when you really need kapital. Planet Money is looking for taglines which you can tweet to @planetmoney. Here are a few good ones:

- Vanguard members get double reward points! #marxcard @planetmoney.

- “What’s in YOUR wallet? Seriously, though, I need to see your papers. Now.”

- @planetmoney There are some things money can’t buy. Especially if you abolish all private property. #marxcard.