Category: History

Did Keynes favor planning?

Barkley Rosser and Brad DeLong say no, but it depends on definition and context. Barkley tries to talk his way out of it, but Keynes in the General Theory did advocate “a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment.” “somewhat” — that’s my kind of weasel word! In any case this was not the same as classical central planning circa 1920, but in a rap video I consider that acceptable license. By my count “central plan” comes up once in a ten-minute video and most importantly Keynes does not accept the characterization but rather responds that the debate is about spending. The video is not suggesting that each and every rapped point is true at face value, and if the two characters seem to debate past one another that too reflects the reality at the time.

Also consider another piece of evidence, namely the Keynes-approved preface to the German-language (uh-oh) edition of the General Theory:

Nevertheless the theory of output as a whole, which is what the following book purports to provide, is much more easily adapted to the conditions of a totalitarian state, than is the theory of the production and distribution of a given output produced under conditions of free competition and a large measure of laissez-faire.

Points in response are: a) Keynes does not seem to actually favor the German system, even if he thinks it is better suited to Keynesian doctrine, b) the Nazi system was not “central planning,” and c) this was written in 1936 before the worst acts of the Nazi state, planning or otherwise.

Nonetheless, in Keynes’s time enthusiasm for significant socialistic planning was common. Keynes had it too, at least for a while in the 1930s. It was a milder planning than the worst ideas circulating at the time, but it’s fair game to contrast it with the anti-planning sentiments of Hayek. Can you imagine Hayek writing a preface like that? I don’t think so.

The Lost Eden of Childhood. Not Lost. Not Eden.

Jim Manzi warms to Paul Krugman’s nostalgia:

It’s difficult to convey the almost unbearable sweetness of this kind of American childhood to anybody who didn’t live it. The safety and freedom that Krugman describe are rare now even for the wealthiest Americans – by age 9, I would typically leave the house on a Saturday morning on my bike, tell my parents I was “going out to play,” and not return until dinner; at age 10, would go down to the ocean to swim with friends without supervision all day; and at age 11 would play flashlight tag across dozens of yards for hours after dark. And the sense of equality was real, too. Some people definitely had bigger houses and more things than others, but our lives were remarkably similar. We all went to the same schools together, played on the same teams together, and watched the same TV shows. The idea of having, or being, “help” seemed like something from old movies about another time.

Who doesn’t look upon their childhood with wistfulness for what has been lost? Exile from Eden is one of the oldest stories on record. But don’t mistake personal narrative for reality. When Manzi says “we all went to the same schools together, played on the same teams together, and watched the same TV shows.” He isn’t talking about African Americans. And was the idea of having or being help, really “from a different time”? Again, not for African Americans. In 1950 more than 40% of African American women in the labor force were domestic servants. (Moreover, given these numbers a back of the envelope calculation suggests proportionately fewer homes with maids today.) See also Megan McArdle on Manzi’s vision and women staying at home.

Growing up in Northern Virginia, my children experience far more ethnic, cultural, racial and sexual diversity and equality than just about any child growing up outside of a commune did in the 1950s and 1960s.

Has childhood freedom been lost? No. Childhood freedom hasn’t been “lost,” it has been taken away by parents. As a child, I too was free to play in the woods but then again my parents didn’t buckle me up in the car, either.

Has safety decreased? It is true that one of the most horrible things we can imagine, homicide, is up. For kids aged 5-14 homicide mortality went from 0.5 per 100,000 in 1950 to 0.8 per 100,000 in 2005. Overall, however, kids are much safer today than in the 1950s. Accident mortality, for example, is down from 22.7 per 100,000 in 1950 to 6.2 per 100,000 in 2005 (see Caplan’s Selfish Reasons for more details). Maybe buckling up and ocean supervision isn’t so bad. Maybe parents today worry too much. Probably some of both.

Has safety decreased? It is true that one of the most horrible things we can imagine, homicide, is up. For kids aged 5-14 homicide mortality went from 0.5 per 100,000 in 1950 to 0.8 per 100,000 in 2005. Overall, however, kids are much safer today than in the 1950s. Accident mortality, for example, is down from 22.7 per 100,000 in 1950 to 6.2 per 100,000 in 2005 (see Caplan’s Selfish Reasons for more details). Maybe buckling up and ocean supervision isn’t so bad. Maybe parents today worry too much. Probably some of both.

There have been big improvements in accident risk since even my childhood years. I remember those idyllic summers of the 1970s earning a few extra dollars mowing lawns–80,000 amputated fingers, hands and mangled toes and feet every year back then and just 6,000 today. Would I even let me kid use a mower from the 1970s? Disease mortality is also way down, from 36.6 per 100,000 in 1950 to 8.6 per 100,000 in 2005. For good or for ill, parental fears have increased even as risks overall have fallen.

There is nothing wrong with a bit of personal nostalgia but when nostalgia is taken for reality it biases our thinking in counter-productive ways. One wonders, for example, what those who look back longingly at the freedom of their childhood would say about Lenore Skenazy and her free-range kids. Skenazy let her fourth-grader take the NYC subway home alone. Would Manzi applaud Skenazy for giving her kids the same freedoms he had? Or would he denounce her, as many parents did, for something tantamount to child-abuse?

Royal wedding markets in everything

Here is the full story, with numerous other examples: “…”the British Cheese Board has put together a William and Kate themed cheese board”. No, really; it says that. They then go on to enumerate five British cheeses and their agonisingly tenuous connection to the principal players; “Wensleydale with cranberry is a fruity blended cheese hailing from Yorkshire, just like Miss Middleton’s father””

Bryan Caplan defends pacifism

In the real-world, however, pacifism is a sound guide to action.

And that includes an unwillingness to kill innocent civilians as collateral damage while acting in defense of one’s country. The original post is here, the defense against critics is here.

There is not enough consideration of specific times and place. Had England been pacifist in 1914, that might have yielded a better outcome. Had England been pacifist in 1939, likely not. Switzerland has done better for itself, and likely for the world, by being ready to fight back. Pacifism today could quite possibly doom Taiwan, Israel, large parts of India (from both Pakistan and internal dissent), any government threatened by civil war (who would end up ruling Saudi Arabia and how quickly?), and I predict we would see a larger-scale African tyrant arise, gobbling up non-resisting pacifist neighbors. Would China request the vassalage of any countries, besides Taiwan that is? Would Russia “request” Georgia and the Baltics? Would West Germany have survived?

And this is the best we can do? It’s much worse than the status quo, which is hardly delightful enlightenment. I don’t see these examples mentioned in Bryan’s post. There is also a Lucas critique issue of how the bad guys start behaving once they figure out that the good guys are pacifist, and I don’t see him discussing that either.

It would be a mistake to add up all the wars and say pacifism is still better overall, because we do not face an all-or-nothing choice. Many selective instances of non-pacifism are still a good idea, with benefits substantially in excess of their costs. Bryan, however, has to embrace pacifism, otherwise his moral theory becomes too tangled up in the empirics of the daily newspaper…

Which is exactly where I am urging him to go.

*A Great Leap Forward: 1930s Depression and U.S. Economic Growth*

In his masterpiece, Alexander J. Field writes:

This book is built around a novel claim: potential output grew dramatically across the Depression years (1929-1941), and this advance provided the foundation for the economic and military success of the United States during the Second World War, as well as for what Walt Rostow (1960) called “the age of high mass consumption” that followed. This view, if accepted, leads to important revisions in our understanding of the sources and trajectory of economic growth to the second quarter of the century and, more broadly, over the longer sweep of U.S. economic history since the Civil War.

…Although the Second World War provided a massive fiscal and monetary boost that eliminated the remnants of Depression-era unemployment, it was, on balance, disruptive of the forward pace of technological progress in the private sector.

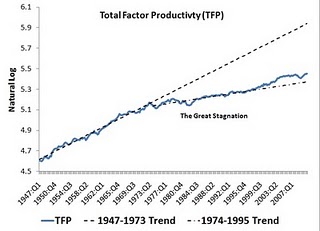

During 1929-1941, the annual total factor productivity (measure of economic progress due to new ideas) increase in the trucking sector was 12.61 (!) and for airline transport it was 14.45 (!).

This is a) one of the best economics books of the last ten years, b) one of the best books on the Depression era, c) the only economic interpretation of WWII which makes sense, and is supported by the numbers, and d) one of the must-reads of the year.

Here is an interview with Field. You can buy the book here.

*Levant* (Smyrna, Alexandria, and Beirut)

That is the new and excellent book by Philip Mansel and the subtitle is Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean, excerpt:

The Beirut dilemma goes to the heart of the Levant. At certain times — Smyrna in the nineteenth century, Alexandria and Beirut for periods of the twentieth — Levantine cities could find the elixir of coexistence, putting deals before ideals, the needs of the city before the demands of nationalism. Like all cities, however, Levantine cities needed an armed force for protection. This could be provided by the Ottoman, British or French armies, but not by the cities’ own citizens, since they were unwilling to shoot co-religionists. No Levantine city produced an effective police force or national guard of its own. The very qualities that gave these cities their energy — freedom and diversity — also threatened their existence. No army, no city.

*In the First Circle*

I was reading Solzhenitsyn’s novel during my time in Brazil and I believe he has become oddly underrated. He is too often viewed as a historical artifact rather than as one of his century’s best writers. Here was one of my favorite passages from what is perhaps his best novel (Cancer Ward is another favorite):

“My husband’s been in prison nearly five years,” she said. “And before that he was at the front…”

“That doesn’t count,” the woman retorted. “Being at the front isn’t the same thing! Waiting is easy then! Everybody else is waiting too. You can talk about it openly; you can read his letters to people. But when you have to wait and keep quiet about him, that’s something else.”

*The Origins of Political Order*

That is the new book from Frank Fukuyama and the subtitle is From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. A few points:

1. Every page is intelligent and reasonable.

2. It is a useful general overview of what we know about the origins of states, with full coverage given to the non-Western world, most of all China.

3. My single sentence summary would be: “I am showing you how some polities developed workable, strong states, based in accountability, and how others did not.” If that is it, I would rather that the empirical material were more focused on the “model” and less on overall general narrative. Ultimately the organization sprawls. Nonetheless, this book is an important implied revision of public choice economics, with the focus on history and the question of how strong states get built.

4. In its scope and method, this book feels late 19th century.

5. I am not convinced by the discussion of why earlier China did not progress, found in the range of 51% on Kindle. Fukuyama seems to suggest they simply weren’t interested in doing better. I would be happier if so much did not rest on that question.

6. One implication of the analysis is that we should not be very optimistic about the current revolutions in the Middle East.

7. Try this sentence: “The very lateness of the European state-building project was the source of the political liberty that Europeans would later enjoy.”

8. The section on biology could use a major dose of Robin Hanson.

Here is one useful review. Here is a review from The Economist.

Debunking Bartels on the Democrats

Larry Bartels has an oft-cited that Democratic Presidents are better for the economy. Andrew Gelman has a nice presentation of the skeptical take of Jim Campbell. For instance:

Jim Campbell recently wrote an article, to appear this week in The Forum (the link should become active once the issue is officially published) claiming that Bartels is all wrong–or, more precisely, that Bartels’s finding of systematic differences in performance between Democratic and Republican presidents is not robust and goes away when you control the economic performance leading in to a president’s term.

Here’s Campbell:

Previous estimates did not properly take into account the lagged effects of the economy. Once lagged economic effects are taken into account, party differences in economic performance are shown to be the effects of economic conditions inherited from the previous president and not the consequence of real policy differences. Specifically, the economy was in recession when Republican presidents became responsible for the economy in each of the four post-1948 transitions from Democratic to Republican presidents. This was not the case for the transitions from Republicans to Democrats. When economic conditions leading into a year are taken into account, there are no presidential party differences with respect to growth, unemployment, or income inequality.

File under “Was never convincing in the first place.” Read the comments to the post also.

Best Rejection Letter Ever

…it is with no inconsiderable degree of reluctance that I decline the offer of any Paper from you. I think, however, you will under reconsideration of the subject be of the opinion that I have no other alternative. The subjects you propose for a series of Mathematical and Metaphysical Essays are so very profound, that there is perhaps not a single subscriber to our Journal who could follow them.

Sir David Brewster editor of The Edinburgh Journal of Science to Charles Babbage on July 3, 1821. Noted in James Gleick’s, The Information.

“When and where do great feats of architecture come about?”

The post is interesting throughout, but these are the two best paragraphs:

Transparency

You only need to impress someone when there is asymmetric information, where that someone does not know how great you are. Shah Jahan needed to build big because the targets of his attention did not know the GDP of his dominion and his tax/GDP ratio. In this age of Forbes league tables, Mukesh Ambani does not need to build a fabulous structure for you to know he’s the richest guy in India. A merely functional house suffices; a great feat of architecture is not undertaken.

Accountability The incremental expense of going from a merely functional structure to a great feat of architecture is generally hard to justify. Hence, one might expect to see more interesting architecture from autocratic places+periods, where decision makers wield discretionary power with weak checks and balances. As an example, I think that Britain had the greatest empire, but the architecture of the European continent is superior: this may have to do with the early flowering of democracy in the UK.

For the pointer I thank Yogesh. Three older posts of relevance are here and here and most of all here.

Vaclav Smil

His books are excellent, you probably should read them all.

His Energy Myths and Realities: Bringing Science to the Energy Policy Debate is depressing, excerpt:

A world without fossil fuel combustion is highly desirable, and, to be optimistic, our collective determination, commitment, and persistence could accelerate its arrival. But getting there will be expensive and will require considerable patience. Coming energy transitions will unfold, as the past ones have done, across decades, not years.

And this:

…do not underestimate the persistence and adaptability of old resources (remember that coal is still more important globally than natural gas) and established prime movers, particularly those that have been around for more than a century, including steam turbines and internal combustion engines. Recall that the latest incarnations of the internal combustion engine, the new DiesOtto machines, have the potential to be more efficient than the best hybrid drives on today’s market.

My favorite book by him is Prime Movers of Globalization: The History and Impact of Diesel Engines and Gas Turbines, a better title and subtitle there never was.

*Before the Revolution*

The author is Daniel K. Richter and the subtitle is America’s Ancient Pasts. I admit I am a sucker for books on this topic, but so far it is one of my two or three favorite non-fiction titles of the year. Excerpt:

The end of the Chesapeake chiefs’ efforts to use prestige goods to build power in the traditional way resulted from a more basic factor than the violent refusal of the English to play along. Once substantial numbers of European and Native people began living near each other, it became virtually impossible for any chief to control the flow of goods to his people, even if, as Powhatan apparently tried to do, he redefined prestige in ever more esoteric directions. As early as January 1608 — only a few months after the establishment of Jamestown — Smith complained that ordinary colonists and visiting sailors were trading so much metal to ordinary Indians that corn and furs “could not be had for a pound of copper, which before was sold for an ounce.” Archaeological excavations confirm that the jewelers and metalworkers textbooks have long derided as useless appendages to the lazy Jamestown colonists worked busily to make copper and other metal items to trade with Native people. This might have been the colony’s only productive enterprise in its earliest years. All along the costs — and soon along the interior rivers — of eastern North America, this kind of unregulated trade between commoners was bad news for chiefs like Powhatan, whose power depended on European goods remaining rare and under their personal control. But the opportunities that such trade represented — for both Europeans and Native people — were enormous. Some chiefs found ways to turn the new conditions to their advantage. Others did not.

Definitely recommended. My favorite parts are about the agricultural revolutions experienced in native American societies, before the arrival of the colonists. Here is part of the Amazon summary:

Richter recovers the lives of a stunning array of peoples—Indians, Spaniards, French, Dutch, Africans, English—as they struggled with one another and with their own people for control of land and resources. Their struggles occurred in a global context and built upon the remains of what came before. Gradually and unpredictably, distinctive patterns of North American culture took shape on a continent where no one yet imagined there would be nations called the United States, Canada, or Mexico.

Total Factor Productivity

What determined the playing length of an audio CD?

Here is one account:

Sony had initially preferred a smaller diameter, but soon after the beginning of the collaboration started to argue vehemently for a diameter of 120mm. Sony’s argument was simple and compelling: to maximize the consumer appear of a switch to the new technology, any major piece of music needed to fit on a single CD…Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was quickly identified as the point of reference — according to some accounts, it was the favorite piece of Sony vice-president Norio Ohga’s wife. And thorough research identified the 1951 recording by the orchestra of the Bayreuther Festspiele under Wilhelm Furtwängler, at seventy-four minutes, as the slowest performance of the Ninth Symphony on record. And so, according to the official history, Sony and Philips top executives agreed in their May 1980 meeting that “a diameter of 12 centimeters was required for this playing time.”

That is from the new and interesting book by Tim Büthe and Walter Mattli, The New Global Rulers: The Privatization of Regulation in the World Economy, the book’s home page, with free chapter one, is here. Speaking of which, Garth Saloner is another very good South African economist and he is now Dean of Stanford Business School.