Category: History

Good paragraph, bad paragraph

The best riposte to Bill Kristol comes from Hayek. He pointed out years ago–sorry, don’t have time to track down the citation–that the idea of small government was vital even if there was no prospect of its ever being achieved. So powerful and varied was the pressure in and on government for every kind of new spending that an automatic barrier was necessary to prevent the fiscal river sweeping all before it. A general prejudice against higher spending and taxes served as such a barrier. It might not prevent all or even most spending, but it would stop some. It would compel the government to think through its spending priorities and to confine them all within or nearly within taxable capacity. And though the government would probably grow anyway, it might grow less because of the prejudice that it should not grow at all.

If we were lucky, a barrier might even gain a quasi religious status over time, as the Gold Standard did in England until the first world war, and instill in voters the fear that tampering with it would be an impious act or even simply impossible. This worked for quite a while. When the Tories floated the pound in 1931, a former Labour minister, Lord Passfield (aka Sidney of Sidney and Beatrice Webb) said: "They never told us we could do that."

That is from John O’Sullivan. The question is whether the worrying paragraph undoes the goodness of the good paragraph. England, of course, would have done better to go off the gold standard much earlier than it did, or if it had not revalued the pound at an artificially high rate after the first World War.

The Capital Strike

Roosevelt went on in later weeks to speculate that the slowdown in investment was not economically explicable but was, rather, part of a political conspiracy against him, a "capital strike" designed to dislodge him from office and destroy the New Deal…In a reprise of his tactics in the "wealth tax" battle of 1935 and the electoral campaign of 1936, Roosevelt loosed Assistant Attorney General Robert Jackson, along with Ickes, to give a series of blistering speeches in December 1937. Ickes inveighed against Henry Ford, Tom Girdler and the "Sixty Families,"…Left unchecked, Ickes thundered, they would create "big-business Fascist America – an enslaved America." For his part, Jackson decried the slump in private investment as "a general strike – the first general strike in America – a strike against the government – a strike to coerce political action." Roosevelt even ordered an FBI investigation of possible criminal conspiracy in the alleged capitalist strike, but it revealed nothing of substance.

(From David M. Kennedy’s Freedom from Fear (p. 352) in The Oxford History of the United States.)

A group of capitalists go on strike to protest a government that is confiscating their wealth. The government vows to force them back to work and sets agents on their trail. Hmmm…..seems like there could be a novel in that.

Changes in money wages

And what Keynes had to say then is as valid as ever: under

depression-type conditions, with short-term interest rates near zero,

there’s no reason to think that lower wages for all workers – as opposed to lower wages for a particular group of workers – would lead to higher employment.

Suppose that wages across the US economy had been, say, 20 percent

lower than they actually were. You might be tempted to say that this

would make hiring workers more attractive. But to a first

approximation, prices would also have been 20 percent lower – so the

real wage would not have been reduced. So how would lower wages lead to

higher demand for labor?

Well, the real money supply would have been larger – but the normal

channel through which this might increase demand, lower interest rates,

was blocked by the zero lower bound. Yes, there would have been a

slight Pigou effect: real private sector wealth would have been higher,

because cash under the mattress (or wherever) was worth more. But on

the other hand, real debt burdens would also have been higher, probably

exerting a contractionary effect. Overall, there’s no good reason to

think that lower wages would have helped raise employment.

That is Paul Krugman and also here. That is correct but note the argument requires lower wages for all workers, exactly as Krugman states. He does not go through a change in wages for only some workers and indeed that scenario is very different and not necessarily Keynesian. When unemployment is present, lower wages for some workers can stimulate renewed employment and — depending on elasticities — possibly greater purchasing power as well or at least not proportionally diminished purchasing power. (Each worker earns less but there are more workers employed.) There won't in general be much of a deflation. The hiring of some workers can also lead to an upward spiral in production, employment, and again purchasing power, as outlined by W.H. Hutt in his books on Keynes.

Krugman and others wish to argue that the New Deal years were ones of recovery; that is fine but it increases the chance that the Hutt scenario and not the Keynes scenario would apply at that time.

The simplest version of the Keynesian argument on money wages also relies on labor as the primary source of marginal cost (true in many but not all sectors) and lack of market power for retail prices, among other assumptions about market structure. Yet another scenario is that some nominal wages fall and entrepreneurs (with some market power) invest more in response and hold retail prices relatively steady.

I believe Keynes's "falling nominal wages-falling prices-constant real wages-constant unemployment" scenario does hold for some of the 1929-1932 period and indeed I have argued as such in print. But once we get into the Roosevelt era, we have government propping up some wages above market-clearing levels and thus higher than necessary unemployment. Note that the Roosevelt policies applied only to some workers and by no means to all or even most workers, which again suggests the Hutt analysis is more relevant than the Krugman/Keynes analysis.

Krugman asks why Keynes's point, presented in 1936, is not more widely recognized today. But the limitations of Keynes's argument — including its reliance upon particular assumptions about cost and market structure — were pointed out by Jacob Viner in…1937 (see pp.161-162 JSTOR).

Viner, I might add, was hardly a laissez-faire denialist. He favored an active government response to the depression, and he admits Keynes's results can hold but needn't hold. He is the one who stakes out the sophisticated middle ground, not Keynes. So we're still trying to catch up to 1937, not 1936.

Addendum: It turns out I am blogging chapter 19 of the General Theory; I am looking forward to our forthcoming book club too much!

Fiscal policy poll

What are the times in history — whether in the U.S. or elsewhere — when a large-scale application of expansionary fiscal policy has been effective in raising a country out of a recession or depression?

I’ve already discussed World War II and the United States, so whether or not you agree with me there is no need to mention that episode again. I’m not (yet) looking for a debate rather I am conducting an opinion poll. Over the next few weeks or months I hope to investigate some of the cases you mention and see what is the verdict of history.

What are the lessons from the New Deal?

This week they put my Sunday column on the web on Friday; I was alerted by the ever-vigilant Mark Thoma. The intro is this:

The traditional story is that President Franklin D. Roosevelt rescued capitalism by resorting to extensive government intervention;

the truth is that Roosevelt changed course from year to year, trying a

mix of policies, some good and some bad. It’s worth sorting through

this grab bag now, to evaluate whether any of these policies might be

helpful.If I were preparing a “New Deal crib sheet,” I would start with the following lessons…

The conclusion is this:

In short, expansionary monetary policy and wartime orders from Europe,

not the well-known policies of the New Deal, did the most to make the

American economy climb out of the Depression. Our current downturn will

end as well someday, and, as in the ’30s, the recovery will probably

come for reasons that have little to do with most policy initiatives.

Read the whole thing. For critical responses, perhaps you can try the comments section at Mark Thoma’s. For reasons of space, it was not possible to specify that I was praising the proposed Obama middle-class tax cut. I do not, however, think it will do much (if anything) to end the current recession, although tax hikes could make things worse.

Markets in everything?

The new claim is that a woolly mammoth could be regenerated for as little as $10 million. The basic technique, as I understand it, is reconstructing the genome of the mammoth and modifying the DNA in the egg of a modern elephant and bringing the final-stage egg to term in an elephant mother. It is noted that the same will be possible with Neanderthals, as it is expected that their genome will be recovered and sequenced shortly.

Didn’t I read as recently as ten years ago that "Jurassic Park" scenarios were more or less impossible? I don’t expect Neanderthal man to reappear soon, but assuming the world stays (relatively) peaceful and wealthy, what is the chance of seeing one or more such beings within the next two hundred years? Yes I know all about the law, eventual demographics, and the fear of planet-wide interspecies war, but at $10 million and over one hundred countries in the world, is not private philanthropy robust?

As one commentator asks, if we humans killed them off in the first place, does that mean we have any obligation to revive them now?

Investment in the Great Depression

Brad DeLong shows a graph of how Gross Private Domestic Investment rises during the New Deal, except for the contractionary 1937-8 downturn. The pattern is striking.

A loyal MR reader emails me a citation to Robert Higgs’s book, which on Google (pp.6-7) claims that net investment was negative over the 1930-35 period. There is talk of a "capital consumption allowance" and that allowance accounts for the difference between the gross and the net terms. Only in 1941 did net investment exceed its 1929 level. Here’s a chart which seems consistent with these claims and which shows the difference between the net and the gross series for investment. The waves are very similar but at different absolute levels.

Can any readers explain what is going on In this time period, using this data, is net or gross investment a better indicator of recovery and economic conditions? Is the pro-New Deal claim that making net investment "less negative" (but still negative) counts as a success or rather that the gross investment series is what matters?

When I look at this data series — whether gross or net — I see a few monetary policy actions (initial reflation, breaking the old link to gold, increasing reserve requirements in 1936) as the dominant explanatory variables.

Father Time

Watching Star Wars today is like watching It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) in 1977.

Here are more such comparisons.

Sentences to ponder

The scientific method & capitalism are similarly inhuman systems. They also happen to be the primary sources of our progress.

That is Kebko, from the MR comments section.

Now is the Time for the Buffalo Commons

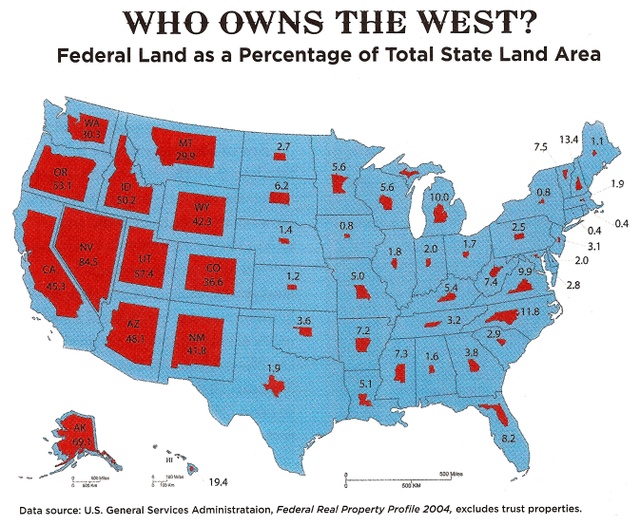

The Federal Government owns more than half of Oregon, Utah, Nevada, Idaho and Alaska and it owns nearly half of California, Arizona, New Mexico and Wyoming. See the map for more. It is time for a sale. Selling even some western land could raise hundreds of billions of dollars – perhaps trillions of dollars – for the Federal government at a time when the funds are badly needed and no one want to raise taxes. At the same time, a sale of western land would improve the efficiency of land allocation.

Does a sale of western lands mean reducing national parkland? No, first much of the land isn’t parkland. Second, I propose a deal. The government should sell some of its most valuable land in the west and use some of the proceeds to buy low-price land in the Great Plains.

The western Great Plains are emptying of people. Some 322 of the 443 Plains counties have lost population since 1930 and a majority have lost population since 1990.

Now is the time for the Federal government to sell high-priced land in the West, use some of the proceeds to deal with current problems and use some of the proceeds to buy low-priced land in the Plains creating the world’s largest nature park, The Buffalo Commons.

Hat tip to Carl Close for the pointer to the map.

What ended the Great Depression?

There has been recent circulation of the older view that it is World War II, as a kind of giant public works project, which ended the Great Depression. This claim is not consistent with our best knowledge of the subject. To survey the cutting edge of the literature briefly:

Christina Romer writes:

This paper examines the role of aggregate demand stimulus in ending the

Great Depression. A simple calculation indicates that nearly all of the

observed recovery of the U.S. economy prior to 1942 was due to monetary

expansion. Huge gold inflows in the mid- and late-1930s swelled the

U.S. money stock and appear to have stimulated the economy by lowering

real interest rates and encouraging investment spending and purchases

of durable goods. The finding that monetary developments were crucial

to the recovery implies that self-correction played little role in the

growth of real output between 1933 and 1942.

Here is another interesting paper on the topic; it focuses on productivity issues and mean reversion. Here is from a paper by Cullen and Fishback:

We examine whether local economies that were the centers of federal

spending on military mobilization experienced more rapid growth in

consumer economic activity than other areas. We have combined

information from a wide variety of sources into a data set that allows

us to estimate a reduced-form relationship between retail sales per

capita growth (1939-1948, 1939-1954, 1939-1958) and federal war

spending per capita from 1940 through 1945. The results show that the

World War II spending had virtually no effect on the growth rates in

consumption that we examined.

Further debunking of the WWII idea can be found in this paper by Robert Higgs, who stresses the difference between standard gdp measures and actual economic welfare.

I also find the experience of the Latin American economies convincing. The economic recovery of Argentina, for instance, clearly was due to monetary policy, not fiscal policy, which remained tight throughout the period of recovery. Mexico recovered from the Great Depression relatively quickly and this history also does not fit the fiscal policy view. Later on, most of the Latin economies experienced commodity booms because of wartime demands and again this was not fiscal policy and of course they were not fighting the war themselves. The two countries where fiscal policy played a significant role in recovery are, not surprisingly, Germany and Japan and here I am referring to their prewar spending.

Ben Bernanke on the New Deal

I’ve been rereading some of the essays in Ben Bernanke’s Essays on the Great Depression, which of course is self-recommending. I thought this passage summed up some relevant truths:

Our [with Martin Parkinson] own view is that the New Deal is better characterized as having "cleared the way" for a natural recovery (for example, by ending deflation and rehabilitating the financial system), rather than as being the engine of recovery itself.

Bernanke notes that there were "remarkably strong" productivity gains throughout much of the 1930s, even though there was no capital deepening. This is a central puzzle which any account of the New Deal, or New Deal recovery, must incorporate. These gains seem to span more sectors than could be accounted for by New Deal policy alone, and note that most government interventions, even good ones, don’t bring productivity gains over such a short time horizon and in such a regular and sustained fashion.

Bernanke does suggest that some of the gains came from forced unionization and "efficiency wage" effects and yes that would credit the New Deal. But I doubt that is the best hypothesis and of course it contradicts the traditional account of profit-seeking behavior from businesses (why weren’t they paying the higher wages in the first place?). Rick Szostak’s work suggests that the New Deal saw lots of labor-saving, process innovations, which meant both high productivity gains and pressure on labor markets at the same time. In my view most of these gains were simply the result of working through the implications of the earlier fundamental breakthroughs of the preceding twenty years.

Whatever is the case (and we genuinely don’t know), these productivity gains are central to the story of New Deal recovery. Roosevelt may deserve credit for some of them, or for allowing them to proceed, but don’t assume that the New Deal caused such gains just because you see them in the gross data.

You can find different drafts of the relevant Bernanke-Parkinson paper here, with various forms of gating.

Heroes and Cowards, part II

The single most important determinant of camp survival was the number of men in POW camps. If everyone had been in a camp holding 7,500 men, survival probabilities would have been less than 60 percent instead of more than 80 percent. With greater camp populations survival probabilities would have been even lower. Another important determinant of camp survival was age. Had all men been of Thomas Withington’s age (47), only 70 percent of them would have survived. The next most important determinants of camp survivial were the number of friends, rank, and height. Men who were not either commissioned or noncommissioned officers fared poorly, as did those with no friends and those of Hnery Haven’s height.

Of course that is from the Civil War and it is from the new book by Dora Costa and Matthew Kahn. Here is my previous post about the book, see also the links suggested by Matt in the comments. You can buy the book here.

Unemployment During the Great Depression

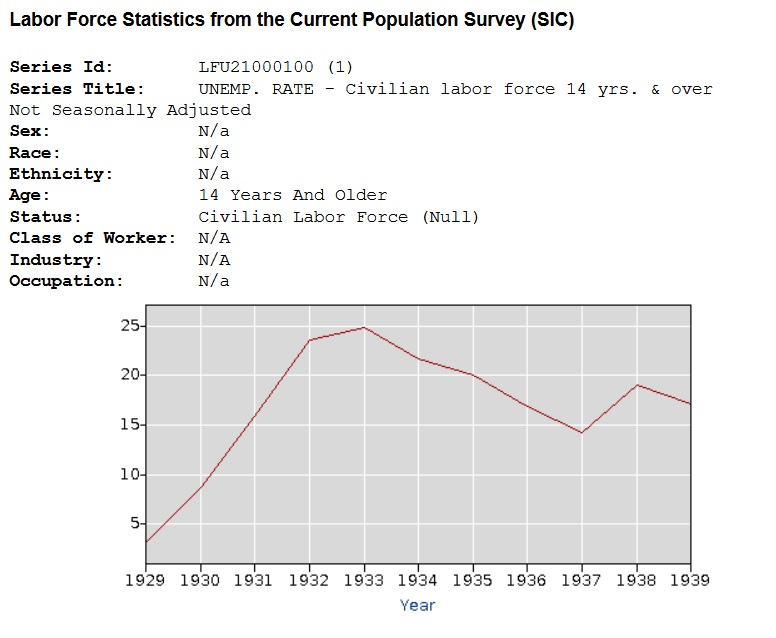

Regarding unemployment during the Great Depression, Andrew Wilson writing at the WSJ recently said:

As late as 1938, after almost a decade of governmental “pump priming,” almost one out of five workers remained unemployed.

Historian Eric Rauchway says this is a lie, a lie spread by conservatives to besmirch the sainted FDR. Nonsense. In 1938 the unemployment rate was 19.1%, i.e. almost one out of five workers was unemployed, this is from the official Bureau of Census/Bureau of Labor Statistics data series for the 1930s. You can find the series in Historical Statistics of the United States here (big PDF) or here. The graph is at right. Rauchway knows this but wants to measure unemployment using an alternative series which shows a lower unemployment rate in 1938 (12.5%). Nothing wrong with that but there’s no reason to call people who use the official series liars.

Historian Eric Rauchway says this is a lie, a lie spread by conservatives to besmirch the sainted FDR. Nonsense. In 1938 the unemployment rate was 19.1%, i.e. almost one out of five workers was unemployed, this is from the official Bureau of Census/Bureau of Labor Statistics data series for the 1930s. You can find the series in Historical Statistics of the United States here (big PDF) or here. The graph is at right. Rauchway knows this but wants to measure unemployment using an alternative series which shows a lower unemployment rate in 1938 (12.5%). Nothing wrong with that but there’s no reason to call people who use the official series liars.

So why are there multiple series on unemployment for the 1930s? The reason is that the current sampling method of estimation was not developed until 1940, thus unemployment rates prior to this time have to be estimated and this leads to some judgment calls. The primary judgment call is what do about people on work relief. The official series counts these people as unemployed.

Rauchway thinks that counting people on work-relief as unemployed is a right-wing plot. If so, it is a right-wing plot that exists to this day because people who are on workfare, the modern version of work relief, are also counted as unemployed. Now if Rauchway wants to lower all estimates of unemployment, including those under say George W. Bush, then at least that would be even-handed but lowering unemployment rates just under the Presidents you like hardly seems like fair play.

Moreover, it’s quite reasonable to count people on work-relief as unemployed. Notice that if we counted people on work-relief as employed then eliminating unemployment would be very easy – just require everyone on any kind of unemployment relief to lick stamps. Of course if we made this change, politicians would immediately conspire to hide as much unemployment as possible behind the fig leaf of workfare/work-relief.

There is a second reason we may not want to count people on work-relief as employed and that is if we are interested in the effect of the New Deal on the private economy. In other words, did the fiscal stimulus work to restore the economy and get people back to work? Well, we can’t answer that question using unemployment statistics if we count people on work-relief as employed. Notice that this was precisely the context of the WSJ quote.

One final thing that one could do is count people on work-relief as neither employed nor unemployed, i.e. not part of the labor force which is what we do for people in the military. Rauchway has data on this and it shows almost the same thing, nearly one in five unemployed, as the original series. (In this case, however, Rauchway counts nearly one in five unemployed as a win for the New Deal because the same series also shows higher unemployment earlier in the Great Depression.)

Any way you slice it there is no right-wing plot to raise unemployment rates during the New Deal and a historian should not go around calling people liars just because their judgment offends his wish-conclusions.

Hat tip to Mark Thoma.

Heroes and Cowards: The Social Face of War

Company socioeconomic and demographic diversity was the single most important predictor of desertion [in the Civil War].

Age and occupational diversity were especially important. For all-black regiments, former slave status (or not) and plantation of origin are important diversity measures for predicting desertion.

That is from the forthcoming book by Dora L. Costa and Matthew E. Kahn. I have not yet finished it but I believe this book will make a big splash. Here is the book’s home page. Here is a blog post by Matt Kahn on the book. Here is Matt Kahn on holding hands.