Against obviousness

Things can be obvious if they are simple. If something complicated is

obvious, such as anything that anybody seriously studies, then for it

to be simple you must be abstracting it a lot. When people find such

things obvious, what they often mean is that the abstraction is so

clear and simple its implications are unarguable. This is answering the

wrong question. Most of the reasons such conclusions might be false are

hidden in what you abstracted away. The question is whether you have

the right abstraction for reality, not whether the abstraction has the

implications it seems to.

That's from Katja Grace. Here is a good post on murder and evil.

Addendum: I liked this bit too:

Perhaps mysterious forces are just more trustworthy than social

institutions? Or perhaps karma seems nice because its promotion is read

as ‘everyone will get what they deserve’, while markets seem nasty

because their promotion is read as ‘everyone deserves what they’ve

got’. Better ideas?

What I’ve been reading

1. The Idea of Justice, by Amartya Sen. This book is 415 pages of intelligent Sen-isms. Key themes are the importance of public reasoning, the plurality of reasons, and the possibility of an impartial approach to major ethical questions. We also learn that in 1938 Wittgenstein was determined to go to Vienna and give Hitler a stern lecture; he had to be talked out of it. At the end of it all I was more rather than less confused about what impartiality means. I don't blame that on Sen, but that says more about the book than any particular comment which I might make. It's a very good introduction to Sen's ethical thought but it's ultimately the Wittgenstein anecdote which sticks with me.

2. Await Your Reply, by Dan Chaon. This tripartite mystery about reinventing yourself has received rave reviews and Amazon readers are strongly positive. I read about one hundred pages and thought it was ably done but of no real substance.

3. How to Make Love to Adrian Colesberry, by Adrian Colesberry. My god this book is sick and I feel bad even telling you about it. It's exactly what the title promises and it has no business being discussed on a family-oriented economics blog. The language is explicit and the content is disgusting. It's also brilliant, funny, and unique. How often do I see a new approach to what a book can be? Once you get past the language and topic, it's actually about narcissism, why empathy is scarce, how we form self-images, how men classify and remember their pasts, and why management fad books are absurd.

4. A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster, by Rebecca Solnit. For many people

this may be a good book but I could not read far into it. The main

thesis is quite interesting, namely that people forms immediate islands

of community and cooperation during very trying times. The examples

include the San Francisco and Mexico City earthquakes, 9/11, and

Hurricane Katrina. But I found the ratio of information to page was

too low for my admittedly extreme tastes.

Here is an interesting bit on how emergencies inspire crowd cooperation, not panic.

5. Das Museum der Unschuld, by Orhan Pamuk. That's The Museum of Innocence in English, out in late October, but I found the German-language version in Stockholm. It's in his "Istanbul nostalgic" mode rather than his "I'm trying to be like Italo Calvino" style and it promises to be one of his very best books.

The Inheritance of Education

Economix posted a graph showing a strong positive correlation between SAT score and parental income. Greg Mankiw pointed out that the effect is unlikely to be purely causal because there may be an omitted variable bias, IQ for example. Paul Krugman and Matt Yglesias both attack Mankiw and point to graphs showing that income matters for college completion and enrollment, respectively, holding various achievement scores constant. Brad DeLong crunches the numbers on IQ and income correlation to estimate that half the effect is due to IQ and half to something else.

All this is good but none if it gets at the heart of the matter because there are a lot of way that heredity/genes could explain the income/education correlation; IQ is only one possible mechanism, personality (e.g. conscientiousness) is another possibility.

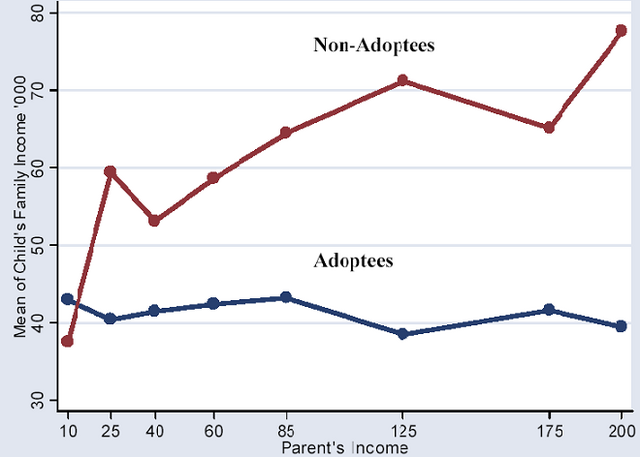

The type of evidence that we need to resolve this question is adoption studies. Fortunately, such studies have been done and indeed I have presented the data before in my post Nature, Nurture and Income. Let's do so again.

The graph below is from What Happens When We Randomly Assign Children to Families?, by Bruce Sacerdote.

Holt's International Children's Services places children, primarily

Koreans, with families in the United States. Holt has an interesting

proviso to their adoption contract, conditional on being accepted into

the program, children are randomly assigned. Sacerdote has collected

data from children who were adopted between 1970-1980, and thus who

today are in their mid 20's or 30's, and their adoptive parents.

The graph shows how parent income at the time of adoption relates to

child income for the adopted and "biological" (non-adopted) children.

The income of biological children increases strongly with parental

income but the income of adoptive children is flat in parent income.

What does this mean?

The graph does not say that adopted children necessarily have low

income. On the contrary, some have high and some have low income and

the same is true of biological children. What the graph says is that

higher parental income predicts higher child income but only for

biological children and not for adoptees.

Now what about education? Sacerdote looks at that as well. He doesn't have a child SAT-score, parent-income correlation but he does find:

Having a college educated mother increases an adoptee's probability of

graduating from college by 7 percentage points, but raises a biological

child's probability of graduating from college by 26 percentage points.

The effect for father's years of education is even larger; about a ten times larger effect on biological children than on adoptees. Similarly, parent income has a negligible effect, small and not statistically significant, on an adoptee completing college but an 8 times larger and statistically significant effect on a biological child completing college (Table 4, column 3).

Assorted links

2. Photo of Titan.

3. Why it's hard to inflate away the debt.

4. What are the highest circulation periodicals?

5. Beryl Sprinkel passes away at 85.

6. Reihan's web project; "Eventually, I’d like it to be a buzzing hub of Reihan-related activity:

illustrations, videos, posts, perhaps a podcast, crushed skulls,

diamond-encrusted elephant tusks, and more."

Darwin, Magic and Evolution

I believe that Darwin would have enjoyed this video of a chimp being dazzled by a magician; it reveals much about our place in the natural universe.

State Rescission

From an email, sent to all employees, from the Office of the Governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia:

Virginia faces its most critical budget shortfall in several decades and we must do all that we can to reduce spending pressures…

If you are enrolled in the state health plan and have "You Plus One" or "You Plus Two or More" coverage, you will receive a packet of information concerning the audit of eligible dependents. I strongly urge you to provide the necessary information to protect your continued coverage by the state health plan.

You will be asked to sign an affidavit attesting that each of your dependents is eligible to be covered by the state health plan (click here for definitions of eligible dependents).

Participation is required. The health benefits program may initiate spot audits that will require additional documentation of dependent eligibility. The benefit to you and other state employees is that this audit will help keep health care costs down by removing ineligible persons from the state health plan.

How to deal with power-addicted politicians

This has been a fruitful dialog. Two days ago Matt Yglesias made a list of how progressives should respond to the public choice critique of big government:

– This is why it’s important to be a civil libertarian and to be much

more skeptical than the political/media mainstream is of the idea that

what’s at stake in these debates is really a “balance” between a

“security” imperative and some airy “values.” It is overwhelmingly

likely that various secret police powers are simply going to be abused,

rather than put to some productive-but-liberty-infringing use.

– This is also a reason to be skeptical of ideas about discretionary regulatory fine-tuning. You always could

improve outcomes by abandoning rigid rules (with “do what you want”

counting as a rigid rule) but in practice you probably won’t.

– I think this also counts on a reason to prefer systems that rely more on career civil servants

and less on political appointees. Bureaucrats have their own

distinctive psychopathologies, but they’re different, and it’s helpful

to have them in more tension and balance than exists in the United

States.

– It’s also important to have in place systems for effective

monitoring of elected officials. A Canadian voter elects one federal

official–a Member of Parliament. An American elects four–a President,

two Senators, and one Representative. Americans don’t have four times

as much time as Canadians to pay attention to what politicians are

doing or to learn the issues; our politicians are just being monitored

less. When you consider the proliferation of things like independently

elected school boards, district attorneys, sheriffs, etc. keep in mind

that this diffusion of responsibility is a good way for the egomaniacal

to evade responsibility.

– If that leaves us with too few veto points, the thing to do is not to have additional houses of legislature, but Swiss-style (as opposed to California-style) direct democracy, where the actions of a unicameral legislature can be checked by the voters.

I agree with much of the list (for one thing, however, I think voting for a fewer number of politicians will have a very small beneficial effect in terms of voter attention); the question is what should be added to it. "Smaller government" is a question-begging answer even if you favor that outcome. It's a list of what will get you to better governmental outcomes, whatever you think those might be.

Too big to fail fact of the day

Large

banks with more than $100 billion in assets are borrowing at interest

rates 0.34 percentage points lower than the rest of the industry. Back

in 2007, that advantage was only 0.08 percentage points, according to

the FDIC. Such differences can cause huge variance in borrowing costs

given the massive amount of money that flows through banks.

Here is the article and I thank Ralph S. for the pointer.

From the comments

And since I'm rambling and have the floor, every man needs a daughter. ALL of my male friends who had children were changed for the better by having at least one daughter. It is not a wife who socializes a husband, it is a daughter.

The link is here.

Assorted links

A second-best theory of libertarian bailouts

Pete Boettke cannot bring himself to utter those few little words.

Let me nudge him (and others) again and try to make things easier for him. General pro-market or anti-government arguments don't rule out the recent bailouts. Let's take the hardest, least Friedman-friendly case, the insolvent banks. For insolvent banks (and for some of the illiquid banks, which might have failed without bailouts), the alternative to those bailouts is calling in deposit insurance and the bankruptcy courts, both of which are, for better or worse, forms of government intervention. In particular today's bankruptcy procedures are ill-suited for disposing of a large financial institution in a timely manner and this can be considered a form of gross government failure.

Note that even when the Fed "bails out" a large investment bank, or insurance company, they are checking a chain reaction which would likely spread to some commercial banks, thus bringing in deposit insurance as well, not to mention further bankruptcies. And that's not even considering that Congress probably would have stepped in, I'm just looking at laws already on the books.

So if you're "opposed to financial bailouts," as a libertarian, you're not for the market. You're saying that one scheme for governmental disposition is better than another. Of course you are entitled to that opinion but the sheer force of libertarian doctrine is not necessarily on your side. The general pro-market and anti-government arguments are not necessarily on your side. I think it is quite plausible for a libertarian to believe that the Fed is "less bad" than the bankruptcy courts and the FDIC.

Now, all things considered, I don't see why this "libertarian two-step" move should be needed. I think it's enough to simply ask whether the bailouts were a good idea and proceed accordingly. But if you're concerned about compatibility with libertarian principle, this is one simple way of seeing why my view fits right in. In fact I think it is the more libertarian of the views under consideration, as it keeps the very worst of the government interventions on the table at bay.

Addendum: Overall I think U.S. bankruptcy law works fairly well, just not relative to the high speeds of market demands when a major financial institution goes bankrupt; Lehman showed this. This is an under-reported source of "regulatory uncertainty." (Prepackaged bankruptcy ideas may help, possibly.) If you are calling for the application of bankruptcy law to major banks, you are calling forth that regulatory uncertainty and yes I do think it is worse than the regulatory uncertainty from a bailout. The result is that credit markets freeze up and that also leads to other bad interventions. Another set of problems springs from the difference between a bank and bank holding company; current law doesn't handle this well although changes are in the works most likely. Of course it is a kind of "super-libertarian" alternative to abolish deposit insurance in the midst of a crisis, as some of you recommend, would you really do that? I don't think so.

*Ayn Rand and the World She Made*

That's the new Ayn Rand biography, written by Anne C. Heller. It is a truly excellent, first-rate biography, at least up through my current p.111. I know Ayn Rand is an emotional topic for many of you, pro, con, or somewhere in between. But my praise of this book is analogous to how I might praise a biography of Jean Rhys or W.C. Handy. It's simply a very good book by any objective [sic] standard and it should be of interest to any student of intellectual history, American popular fiction, libertarianism, or for that matter American history.

Did you know that Rand met her husband by deliberately tripping him? Or that she received WPA funds during the New Deal?

The author is by no means a "Randian" but she is willing to praise the famous Atlas Shrugged "money speech" as "original, complex, and although somewhat overbearing, beautifully written." She nominates We the Living as Rand's most persuasive work in a literary sense.

Here is one blog review of the book, which is in any case recommended.

What do kids find worth fighting over?

Maybe Alchian and Demsetz would not be surprised:

A team of leading British and American scholars asked 108 sibling pairs in Colorado exactly what they fought about. Parental affection was ranked dead last. Just 9% of the kids said it was to blame for the arguments of competition.

The more common reason the kids were fighting was the same one that was the ruin of Regan and Goneril; sharing the castle's toys. Almost 80% of the older children, and 75% of the younger kids, all said sharing physical possessions — or claiming them as their own — caused the most fights.

Nothing else came close. Although 39% of the younger kids did complain that their fights were about…fights. They claimed, basically, that they started fights to stop their older siblings from hitting them.

That is from the new book NurtureShock, by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman, which I found interesting at times. "Interesting enough to read" is perhaps its category. Here is a WSJ review.

I should add that I don't think the cited research settles the matter. Children might fight over toys as credible signals of parental affection, caring more about the signal than about the toy per se.

A cost-benefit analysis of high-speed rail

Matt Yglesias points us to this survey of costs and benefits from a Dallas-Houston high-speed rail link. I'm not convinced by many of the particulars of the argument, which claims to show that the link is a good idea. For instance will the train line really be built with green energy? Will 80 percent of flyers take the train? Is Madrid-Barcelona a good analogy?

More generally, my jaw dropped when I read the denouement:

In this more comprehensive model that takes into account trivialities like regional population growth and a reality-based route, the annual benefits total $840 million compared with construction and maintenance costs of $810 million.

I'm not sure what discount rates he is using but even if we put that problem aside this screams out: don't do it. Given irreversible investment, lock-in effects, and required hurdle rates of return, this still falls into the "no" category. And that's an estimate from an advocate writing a polemic on behalf of the idea. I'm not even considering the likelihood of inflation on the cost side or the public choice problems with getting a good rather than a bad version of the project. How well has the Northeast corridor been run?

So, on high-speed rail, count me as still unconvinced. Nonetheless if you know of a good cost-benefit study, of a single rail link, not in the Northeast corridor, favoring HSR, let me know in the comments. I'll try to read and report on it.

General remark: It's not about population density per se. It's about how many independent, hard-to-connect nodes the system has and that is why high-speed rail on the whole works better in Europe or Japan than in many other locales. To give an example from a slightly different realm, I live right near the Metro in a high-density suburban area. Yet I don't take the Metro to my Arlington office, which is about two minutes from a Metro stop. I'd rather do the 37-minute drive. Why? Because I stop at the supermarket and the public library on my way home at least half of the time or maybe I stop to eat at Thai Thai. If those conveniences were right next to my house I'd consider the Metro but they're not. The fact that my neighborhood has lots of people doesn't help me any. In Tokyo you could live for years within the confines of many (most?) individual city blocks.

Assorted links

1. What's the chance you'll die in the next year? Here is a new calculator.

2. Markets in everything: revenge flyers.

3. One good way to think about why placebo effects are getting stronger.

4. The conference bike: will it make meetings longer or shorter?