Outsourcing for everything

Why not grade exam papers in India? Brad DeLong offers the link. The obvious question is what we really need professors for anyway — are we simply magnets of personality to keep students interested?

Speaking of Brad, he and Jacqueline Passey have unknowingly combined forces to make me mighty curious about Firefly. The Amazon ratings are in the stratosphere. My TV education continues. But if I ever felt obliged to watch the medium, my already overbooked life would simply fall apart…

Terror Alerts, Police and Crime

If you look at a simple correlation between crime per capita and police per capita you get this:

Police cause crime! Some of the Foucault-inspired may buy into that conclusion but it’s really no surprise that places with a lot of crime have a lot of police. Estimating the true effect of police and crime from observational data is difficult because police and crime are determined jointly.

Ideally, to estimate the true causal effect of police on crime, we would run an experiment, randomly picking weeks in which we increased police presence and observing the effect on crime. Experiments like this, however, are expensive and some might say unethical. If we look carefully, however, we might find natural experiments – times when police presence increased for reasons that are random with respect to crime.

Jon Klick and I look at just such a natural experiment in a paper published in the most recent JLE, Using Terror Alert Levels to Estimate the Effect of Police on Crime (subs. required, free version). When the terror alert system kicks up a notch the police in Washington, DC put more police on the streets. We find that crime in DC drops significiantly during these high-alert periods, especially in the National Mall area where most of the prime terror-targets are located. Street crimes like auto theft and theft from automobiles show especially large decreases when more police hit the street. We find no evidence that tourism or other demand side factors account for the decline in crime.

Gates’ Question

With two simple questions Bill Gates provides us more insight into globalization than half-a-dozen books.

Twenty years ago would you rather have been a B-student in Poughkeepsie or a genius in Shanghai? And today?

That’s Bill Gates, according to Tom Friedman in an interview in the April issue of Wired.

Markets in everything

Aurally frustrated, some deaf hip-hop DJs in East London started setting up their own parties. The kids went mad for it, and soon deaf raves ["Rave" in the UK just means loud DJ party of any sort–Ed.] were drawing hundreds of people from all over the country. I went to one recently at Hackney Ocean and the music was so loud I had to make myself deaf using earplugs.

Inside the club the walls were pulsing to the music but the 500-strong crowd was silent because everybody was just doing excited, drunken sign language. I had no idea what…they were talking about but they were partying way harder than people with ears that work. After years of not being invited to the party, these kids had finally created their own scene and it was exploding.

On stage there was live deaf karaoke where hot deaf girls were frantically signing the lyrics to R&B hits.

Then there was the deaf dance-off, where breakdancers battled to see who was the best at body-popping out of sync to the music.

But the highlight of the night had to be Britain’s first deaf rapper, MC Geezer, who signs-rhymes and raps out of time…

Yes, fixed costs are falling. And thanks to Nacim Bouchtia for the pointer, my apologies if you find the language in the link offensive.

New Econoblog, on estate taxes

Here is the link, I am debating Max Sawicky. My first installment reads as follows:

Whether or to what extent we should have an estate tax will depend on other fiscal choices we make. But the case for an estate tax is not as simple as Max thinks:

1. It is not clear if the estate tax raises much if any revenue. The very rich engage in tax avoidance strategies. The apparent revenue raised is often offset by a lower intake from income and capital gains taxes. Furthermore it has been estimated that the costs of implementing tax avoidance strategies are roughly equal to the (gross) revenue raised.

2. The estate tax does not do much for equality. In fact it increases consumption inequality — presumably the relevant measure — by encouraging the rich to spend more money before they die. Joseph Stiglitz and Alan Blinder have raised this concern.

3. Estate taxes add yet another layer of taxation on savings and investment. Imagine that you must first pay taxes on earned income. You then pay taxes on the income derived from savings and investment. You then face estate taxes when the funds or resources are passed down to the next generation. Savings and investment, of course, are a well spring of economic growth. It is no wonder that the fairness and efficiency of the estate tax has come under such question.

In the early 1990s, Henry Aaron and Alicia Munnell — two liberal economists — wrote: "In short, the estate and gift taxes in the United States have failed to achieve their intended purposes. They raise little revenue. They impose large excess burdens. They are unfair."

Addendum: Here is the permanent link.

I don’t want cellphone use on planes

Bryan Caplan trots out all the usual arguments, you know the ones I use myself when debating opponents of the market. Start with legal laissez-faire and let airlines weigh conflicting preferences and then implement the profit-maximizing policies.

I still don’t want cell phone use on planes, but I’m not going to tell you some fancy-wancy academic story about externalities imposed on infra-marginal consumers. I am still, however, looking for a good argument to use against him. Can I claim that cell phone calls are a socially wasteful means of signaling to your spouse that you care? Can I claim that commercial airplanes are modern (short-term) monasteries, and that markets undersupply such temples of silence?

Politically Incorrect Paper of the Month v.4

This month’s Journal of Law and Economics has several superb papers. Today, I discuss a shocker from Nobelist James Heckman and colleagues, Labor Market Discrimination and Racial Differences in Premarket Factors (subs. required, free version).

A 1996 paper by Neal and Johnson (jstor) showed that most of the black-white wage differential could be explained by AFQT scores. IQ scores, however, can be influenced by schooling and on average blacks receive worse schooling than whites so Heckman et al. control for schooling and look for even earlier measures of ability (Neal and Johnson use teenage scores). The results are not encouraging. After throwing all kinds of factors into the analysis they are able to increase the unexplained wage gap somewhat but no matter how far back they go they still find big ability differences, even in children as young as 1-2 years of age.

The real shock, however, does not come until near the end of the paper where Heckman et al. compare blacks and Hispanics. I will let the authors speak:

Minority deficits in cognitive and noncognitive skills emerge early and then widen. Unequal schooling, neighborhoods, and peers may account for this differential growth in skills, but the main story in the data is not about growth rates but rather about the size of early deficits. Hispanic children start with cognitive and noncognitive deficits similar to those of black children. They also grow up in similarly disadvantaged environments and are likely to attend schools of similar quality. Hispanics complete much less schooling than blacks. Nevertheless, the ability growth by years of schooling is much higher for Hispanics than for blacks. By the time they reach adulthood, Hispanics have significantly higher test scores than do blacks. Conditional on test scores, there is no evidence of an important Hispanic-white wage gap. Our analysis of the Hispanic data illuminates the traditional study of black-white differences and casts doubt on many conventional explanations of these differences since they do not apply to Hispanics, who also suffer from many of the same disadvantages. The failure of the Hispanic-white gap to widen with schooling or age casts doubt on the claim that poor schools and bad neighborhoods are the reasons for the slow growth rate of black test scores.

Which cultures do we tend to undervalue?

Large and insular ones. The Cape Verde islands produce music which is immediately accessible, whether or not you are a local or an insider. The music could not have flourished as it has without external support; the same is true for Jamaican reggae.

On the other hand, you might find that Chinese music sounds like screeching cats being murdered. But in reality, you probably should accept the old saw that 1.3 billion (or however many) people can’t be wrong. Get used to the idea that musical timbre can be as important as traditional harmony, or that shrill voices, loud gongs, and droning background instruments can make for fun.

If you are looking for some Chinese music that won’t offend your Western ears, try the pipa (think elaborate Chinese lute) player Min Xiao-Fen. Here is her home page and some press quotes. Here is a disc to buy. But don’t expect all Chinese music to be so easy.

What about sea cucumber? The Chinese love the culinary texture of smoothness, even if you don’t. Jellyfish is yummy and crunchy, and don’t forget chicken kidney boiled with fishhead. (For real Chinese food in Northern Virginia, try China Star of Fairfax, or Saigon Palace, at Seven Corners, Falls Church, they have the kidney dish, and yes I know Saigon is in Vietnam but a Hong Kong entrepreneur just bought out the old place).

Are you curious and looking for new cultural adventures? Or just seeking a new and difficult way to signal your sophistication? You probably alrerady grasp island cultures relatively well. Spend your marginal time and energy on learning the creations of large and remote foreign territories.

The spectacular images of Hubble

Click through here. Yes I know most of you don’t look at the links, but this is not to be missed. Let’s hope it is not too late to save Hubble as a working piece of equipment.

We are as easy to read as a popular novel

Here are Fog, Flesch, and Kincaid tests applied to MarginalRevolution. We are easier than Time and Newsweek (TC: how about Starsky and Hutch?), though (thank goodness) harder than Reader’s Digest. The Flesch-Kincaid grade suggests that we are suitable reading for sixth graders. Thanks to Steven Bainbridge for the pointer, he in turn thanks Kevin Drum.

TV and the Flynn Effect

Ever notice that old tv shows and movies are boring? Why should this be? Were people more easily entertained thirty years ago? Were they dumber? Why yes, they were.

IQ test scores have been increasing over time, a fact known as the Flynn effect. No one knows exactly why but some ascribe the effect to the greater cognitive demands of modern life. Writing in the NYTimes Magazine Steven Johnson provides some interesting evidence from television. He argues, I think correctly, that the plot structure of television dramas from a generation ago are much simpler than modern equivalents.

The following graph illustrates a typical Starsky and Hutch episode:

The x axis indicates time and the y axis different plot-threads – the opening and closing points are the little "aha" that brings the story full circle with a little comedic twist.

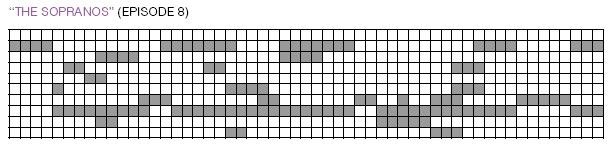

Compare with the Sopranos in which plot-threads and characters interweave across many different episodes:

Is it any wonder that modern viewers are bored by older television?

Johnson wants to argue that the changes in television are part of what is causing the Flynn effect (he doesn’t say this explicitly in the NYTimes article for that you have to read his piece in the April Wired (not yet online) – very meta.) Of course, it’s difficult to say what is cause and what is effect – probably both are involved. (See Dickens and Flynn for more on that theme.)

I liked Johnson’s argument for a new system of tv ratings. Don’t focus on the content focus on the complexity of the content’s presentation.

Instead of a show’s violent or tawdry content, instead of

wardrobe malfunctions or the F-word, the true test should be whether a

given show engages or sedates the mind. Is it a single thread strung

together with predictable punch lines every 30 seconds? Or does it map

a complex social network? Is your on-screen character running around

shooting everything in sight, or is she trying to solve problems and

manage resources? If your kids want to watch reality TV, encourage them

to watch ”Survivor” over ”Fear Factor.” If they want to watch a

mystery show, encourage ”24” over ”Law and Order.” If they want to

play a violent game, encourage Grand Theft Auto over Quake.

Addendum: Ted Frank points out that cable television has added to the phenomena, by fragmenting viewers it has allowed higher quality (less common denominator) content to filter through.

Thanks to our readers

We are pleased to have reached two million hits sooner than we had expected. No, I don’t know exactly what these figures mean, but I do know I wouldn’t be happier if they were lower.

When Alex and I started MarginalRevolution, we vowed to do it for two years, and then evaluate where we stood. Two years is not yet here (September 2005), but I am ready to sign for more. Thank you all for reading us, and also for sending your thoughts and suggestions for material. Special thanks to those who have supported our hosting costs, and our book and newspaper subscription costs, with donations.

Will an aging population lower stock returns?

The study, by James M. Poterba, an economics professor at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has found that changes in the

proportion of retirees in the population have only a modest impact on

stock market returns. So while the market is likely to come under some

downward pressure from the retirement of boomers over the next couple

of decades, he says he believes that there is no reason to expect the

effects to be severe.Professor Poterba’s study, "The Impact

of Population Aging on the Financial Markets," has been circulating

since last autumn as an academic working paper. A copy is at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract-id=609226.He compared the market’s year-to-year returns from 1926 to 2003 with

the annual changes in a number of demographic indicators, including the

proportion of the population in retirement – a phase of life when

investors are presumably net sellers of stock. He also looked at the

share of the population in the 40-to-64 age group – people who tend to

be net buyers of stocks. Regardless of the statistical test used,

however, he found little evidence to support a forecast of a long-term

bear market over the next couple of decades.

That is Mark Hulbert, here is The New York Times link. Surely it is odd that macroeconomics (or finance, for that matter) has so little to say about the determinants of the absolute level of stock prices, no?

Will France ratify the EU Constitution?

Right now the betting market says the chance is a bit more than forty percent. The site, with regular updates, is here. Here is Lynne Kiesling on whether France should ratify.

My take: The Constitution violates many of my political ideals, if only by further cementing a non-accountable Brussels bureaucracy. Nonetheless the EU is a godsend for Eastern Europe, if only by making democracy permanent there. We cannot take that for granted, mostly because Russia has not yet achieved political equilibrium. The benefits for Eastern Europe dwarf any impact on the in-any-case sluggish Western Europe, so let’s root for a smooth constitutional process. The EU will have plenty of time to fall apart later on.

Addendum: Here is a better (more permanent) link, thanks to Chris Massey for the tip.

Bonuses for good governance in Madagascar

Mr. Ravalomanana became president [of Madagascar] and quickly became a favorite for his businesslike style [TC: he was earlier a dairy tycoon]. The president grades his cabinet members, granting the best ministers bonuses far greater than their measly government pay and firing the worst. The economy, which shrank 13% during the turmoil in 2002, has begun to recover although inflation has been a worry recently (WSJ, 18 April, p.A6).

I doubt if this kind of bonus scheme can work more generally, although it remains an interesting question why not. I suspect that it requires an honest and disciplined president, combined with questionable cabinet members who otherwise will not do the right thing. How often do you see that exact combination?

Over time I expect the payments to shift to cabinet members who support the president. Even a benevolent leader will see reason to make the payments in this fashion, but I fear the move toward outright corruption. A private business, in contrast, gains more simply by having subordinates march in tune with the CEO. But we have never worked through all the relevant differences in the two cases. Surely some MR readers would like to see a bonus for Timothy Muris (former FTC head) and a fine imposed on…well…take your pick.

By the way, Madagascar is now the number one poster child for Bush’s Millennium Challenge Account. I know they have wonderful and highly underrated music, but didn’t they have a civil war just a few years ago? I am not yet ready to be bullish on this one.