Month: April 2007

Can Marginal Utility be Measured?

Reporting in the current issue of Neuron, the scientists

reveal that when a small sum of money is on the line, poorer people

learn quickly how to maximize their profits, leaving their wealthier

counterparts in the dust.In a Pavlovian paradigm, a number of abstract shapes flashed

in front of 14 participants. After each shape appeared for three

seconds, a picture of either a 20-pence coin (roughly 40 cents) or a

scrambled image followed. A card of one particular shape was always

followed by the coin, and subjects were told that they could take a

20-pence piece home if they could accurately predict when the money

card was the next one up….The poorer people tended to figure out

which card signaled money ahead within about 12 trials… whereas the

richer people took about 35 trials.The team next repeated the experiment while the subject’s brains

were scanned by an fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging)

machine. …This time, however, the participants did not have to physically respond. "We

didn’t want them to do that because there are neurons in the striatum

that are responding to initiate an action of responding to reward,"

Tobler says. It was this response preparation that the researchers

timed.Once again, an inverse association between wealth and learning

appeared, with poor people displaying more increased activity in the

midbrain and striatum when compared with the more affluent subjects.

From Scientific American, the article is here.

Thanks to Rey Lehmann for the pointer.

Thomas Kaminski has another good observation

I also wonder how anyone in Italy makes a buck. Rome is filled with small shops that apparently provide one small good or service–in my neighborhood alone, there are at least 3 competing herbalists (besides 3 or 4 farmacie), 2 guys who sell stuff for remodeling your bathroom, 4 tire stores or auto repair shops (each in a space no bigger than my living room at home), at least 4 small dry cleaners, 3 barbers, 3 hair dressers for women, a furniture restorer, a guy who sells wood and tile for floors, a different guy who sells only paint, a guy who does hand-painting on china (at least I think that’s what he does), and a dozen other small businesses. In fact, from my limited experience here, Rome seems to have far more small shopkeepers (i.e., small entrepreneurs) than Chicago. And I don’t see how any of the proprietors can make enough to keep his doors open.

And I wonder how so many used book stores survive in the expensive districts of central Paris. I also wonder why Italy has so many stores for fancy underwear, and why so many Italians conduct their arguments out in the street.

Why do businessmen run for public office?

In Italy, on my way back home, these are the papers one’s thoughts turn to:

In immature democracies, businessmen run for public office to gain direct control over policy; in mature democracies they typically rely on other means of influence. We develop a simple model to show that businessmen run for office only when two conditions hold. First, as in many immature democracies, institutions that make reneging on campaign promises costly must be poorly developed. In such environments, office holders have monopoly power that can be used to extract rents, and businessmen run to capture those rents. Second, the returns to businessmen from policy influence must not be too large, as otherwise high rents from holding office draw professional politicians into the race, crowding out businessmen candidates. Analysis of data on Russian gubernatorial elections supports these predictions. Businessman candidates are less likely 1) in regions with high media freedom and government transparency, institutions that raise the cost of reneging on campaign promises, and 2) in regions where returns to policy influence measured by regional resource abundance are large, but only where media are unfree and government nontransparent.

Here is the paper. From the same seminar series, here is a Jim Fearon paper on how democracy minimizes the cost of rebellion.

Why do Jamaicans live so long?

Between 1920 and 1950, Jamaicans added life expectancy at one of the most rapid paces attained in any country.

It is not just Kerala, today Jamaicans live nearly as long as do Americans. James C. Riley wrote Poverty and Life Expectancy: The Jamaica Paradox to tell us why. For the most part he credits public health institutions, most of all education about individual disease hazards.

Recommended, the book is also readable, though the $60.00 price is steep.

Casanova reminds me of Robin Hanson

The girl’s quick mind, unrefined by study, sought to have the advantage of being considered pure and airless; it was conscious of this, and it made use of this consciousness to further its ends; but such a mind had given me too strong an impression of its cleverness.

That is from History of My Life. Is that why human self-deception has evolved? If we don’t know our own artifices, we can more successfully conceal them from others.

A simple model of Europe and America

Dictatorships are generally most brutal when the fear of being overthrown is strongest. The most benevolent dictatorships, in relative terms, tend to have strong roots in the country’s social and economic power centers. This would help explain, for instance, why the minority Sunni Saddam Hussein was so tyrannical against his potential opponents. Without extreme oppression, he would have lost power and his life.

The optimistic scenario for Iraq was (way back when) that a Shiite autocracy, with broad-based public support, would be considerably less brutal. Once in power, the ruling clique would find it much easier to stay in power without extreme brutality. At least that is how the theory went.

In this view, the critical U.S. mistake was not disbanding the (largely Sunni) army, which was in any case inconsistent with the best available power structure. The critical mistake was creating a government that had no real unity and no real chance of having power on the ground.

The pessimistic scenario is that there are no broad-based constituencies left, or perhaps there never were any in the first place. Under the former case American policy has been far more harmful, in net terms, than under the latter case. It is possible that our handling of the transition disbanded whatever broad-based groups were in place to eventually rule. Or perhaps Saddam had already destroyed them.

Partition has a certain logic in this model. But there is no one to effectively oversee the process of division and allocation, either for the population or the oil. I would expect a good million or half million lives to be lost from the resulting slaughter and the forced migrations of population.

To repeat, I am not claiming this model is true. But if it is false, it is worth thinking about what further assumptions should be added or which current assumptions should be dropped.

Addendum: Modeling the current Iraq is difficult for a few reasons. It is rare for an occupying power to set up a democracy, so historical data are scarce. In any case this is not the world of MacArthur and postwar Japan. Nor is it the democracy of Anthony Downs or Arendt Lijphart. For many unusual governmental forms, I start with the implicit models of Gordon Tullock’s Autocracy and the problems of stability and cycling autocratic coalitions. But Iraq seems too far from stability for cycling to be the major problem. The instability seems radically overdetermined, and that makes comparative statics difficult.

The closest parallel I can think of is Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, when relative stability gave way to bloodshed. Fear encouraged a mental overinvestment in strategies of ethnic solidarity and many groups started launching pre-emptive attacks, leading to widening circles of violence and then greater fear.

There are many smart writers on Iraq, with varying degrees of knowledge and information. I wish more of them would seek to provide a simple model of what is going on.

If you do leave comments, please focus on public choice issues rather than attacking or defending the war itself.

Tabarrok in NYC

I will be in NYC tomorrow (Thursday) talking about Bounty Hunters at Victor Niederhoffer’s monthly Junto. All invited. Details here.

Buffett on LTCM

According to Warren Buffet the ill-fated Long Term Capital Management had made the right bets but didn’t have the cash to stay solvent. Buffet wanted to step in and buy the firm but a holiday intervened. Thanks to Newmark’s Door for the pointer.

…Warren wished that he had been able to buy LTCM’s positions when the Fed forced

a resolution of the crisis that was crippling the government bond market.The LTCM crisis was a ready-made example of Warren’s philosophy of buying

firms when the economics was right, yet fear ruled the markets. He noted that

“off-the-run” (non-benchmark) government bonds were selling to yield 30 basis

points more than the “on-the-run” (benchmark) bonds that were maturing just six

months later. He rightly claimed that this made no sense economically.LTCM had taken a huge leveraged position in these bonds when the spreads were

much smaller, but didn’t have the collateral to hold on to it when the spread

widened. Buffett quoted John Maynard Keynes, who wrote in 1931 that “The market

can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.” As the spread widened,

Keynes’ dictum became devastatingly relevant for LTCM. But Berkshire, with its

huge cash hoard, could withstand the pressure of even more market irrationality

before the spread eventually returned to normal.Unfortunately, Warren was never able to consummate the deal. He had been

invited by Bill Gates to vacation in Alaska when the crisis broke and it was

hard to negotiate such a deal on a cell phone… “Bill Gates cost me about $3 billion,” he

shrugged.

Economic deconstructions of rock songs

First comes a quotation from the lyrics, then an analysis, for instance:

"From the Monongaleh valley

To the Mesabi iron range

To the coal mines of Appalacchia

The story’s always the same

Seven-hundred tons of metal a day

Now sir you tell me the world’s changed

Once I made you rich enough

Rich enough to forget my name"This excerpt from Bruce Springsteen’s song "Youngstown" suggests that

he is owed something for making the plant owners rich. According to

economists Paul Gomme and Peter Rupert,

labor’s share of value-added in the nonfinancial corporate sector is

around 74%. Are these perspectives at odds with one another? Please

explain.

Here is the blog, an offshoot from Division of Labor. Here is a discussion of "Rock Island Line." Here is George Harrison’s "Taxman." Thanks to Dan Klein for the pointer.

The latest data on Hispanic assimilation

Find it here, the conclusion is that Hispanics are following traditional immigration patterns and do not represent an outlier, as suggested by Samuel Huntington.

The Italian shortage of small notes

Thomas Kaminski, a loyal MR reader and current resident of Italy, writes to me:

There doesn’t seem to be enough currency in small denominations in circulation. Wherever I buy something, the merchant or cashier seems to ask for smaller bills or coins. Back home in Chicago, if I go into a Starbucks, I don’t give it a second thought if I give the cashier a twenty dollar bill for a $2.50 purchase. They always have plenty of change. Here, even in some supermarket chains, the cashiers constantly ask for exact change or at least for notes in smaller denominations. And when I go to a museum, they often seem to have no change at all…My wife, who is not as familiar with the currency as I am, says that she hates carrying any bill larger than a 10; she constantly gets dirty looks or has to endure sighs of frustration if she tries to buy a cup of tea and doesn’t have small change. And you should see the complications if you try to buy something from a street vendor and don’t have exact change. What is equally annoying, whenever I go to a cash machine, all I get are 50-Euro notes.

I had the same problem in the old days of the Lira, but I am surprised it continues to plague the Euro in Italy and yes I’ve had the same experience here in Venice. Is the Italian central bank simply refusing to print up the right denominations? If so, given Eurofication why don’t the proper size notes flow into Italy where they are most needed? Or should I assume that Italians do not carry socially optimal cash balances at hand? Is there a heavy tax on cash registers and other forms of monetary storage? I remain puzzled.

The best books under 100 pages

What are they? A loyal MR reader wants to know. Comments, of course, are open.

On the Variability of Money and Real Output

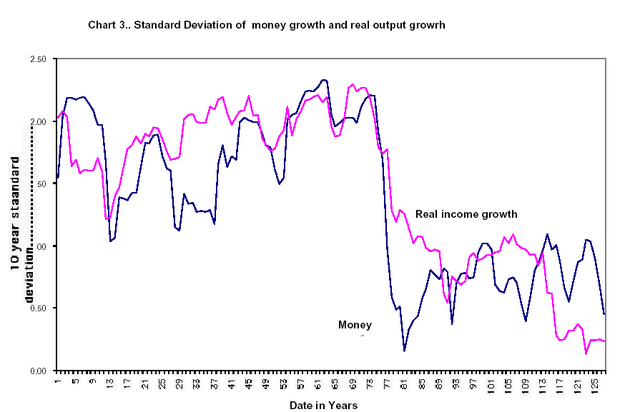

In one of Milton Friedman’s last papers (circa 2006) is this stunning graph. The graph (click to enlarge) shows the standard deviation of real output and money (M2) from 1879 to 2005. The sharp break in the series around the late 1970s and early 1980s is evident – the standard deviation of money fell dramatically and so did the standard deviation of output.

Money is partially endogenous so one could interpret this as running from output to money. The rapidity of the break, however, suggests otherwise. It’s easy to understand how policy could quickly have made money growth more stable. It’s much more difficult to understand how or why real output could quickly become more stable. Moreover, the fact that money stabilized as Volcker and then Greenspan headed the Fed is also suggestive of monetary policy as the driving force.

In one way this is a testament to better monetary policy beginning circa Volcker but in another it’s a damning indictment of how poor monetary policy has been over most of the history of the Federal Reserve.

My favorite Monteverdi

How can the most erotic major composer also be the most underrated major composer? (Could it be that people are ninnies?) Constructing a basic Monteverdi library is simple, you should start with the following:

1. Vespers, his masterpiece. Opt for Andrew Parrott (first choice) or Pearlman (budget label, excellent recording).

2. The Books of Madrigals. The clear first choice is to get the discs by Rinaldo Alessandrini, start with Book Eight, noting the set is incomplete. Second choice would be the collection by Brit Anthony Rooley, beautiful but lacking comparable flourish and diction.

3. L’Orfeo, the opera. Try the Rene Jacobs or John Eliot Gardiner recordings. The Coronation of Poppea has its virtues but it takes much longer to love.

4. Most enjoyable single disc: Monteverdi: Duets and Solos; fewer CDs capture the ecstasy of music and love better than this one.

5. Best way to expand the Monteverdi collection at the margin: Buy more books of madrigals.

Yes Monteverdi is from Mantua but he counts as Venice also. He is a composer I never grow tired of.

Technology, positive liberty, and negative liberty

Randall Parker wrote an interesting sentence:

To state my argument at a philosophical level: Technological advances increase what one can do with one’s positive liberty and by doing that they increase the ease which people can violate negative liberty. This rift came as a result of reading a post by Tyler Cowen on positive and negative liberty.

He has further rapid speculations:

Will rejuvenation therapies lead to such a huge

boost in the world’s population that even the industrialized countries

will fall back into a Malthusian trap? On Darwinian grounds this seems

inevitable. I’ve previously argued that natural selection will reverse the trend of declining fertility in industrialized countries.

Combine that selective pressure with bodies that stay young for

centuries and a population explosion seems inevitable unless either

humans get wiped out by robots or a world government decides we do not

have an unlimited right to reproduce and enforces restrictions on

reproduction.What is nature’s only hope? That rich people decide that owning

their own unspoiled rain forests is a hugely status enhancing form of

consumption. Show your benevolence and wisdom by buying half the Amazon

and let your friends visit its untamed wildness.