Month: October 2008

Why vote?

Economists often argue that voting is a waste of time, since the chance that your vote will influence the election outcome is virtually nil. Maybe, but after watching this fear impels me to the polls.

Thanks for the Scrooge treatment go to loyal reader and GMU student Adam. If anyone knows of something similar for other candidates I will post an addendum.

Marcia Stigum’s *The Money Market*

Often people ask for me background reading about the financial crisis. I recommend blogs first and foremost but still people wish for a brief primer. Well, I can recommend a 1200 page primer, namely Marcia Stigum’s The Money Market, now in its fourth edition. It provides comprehensive coverage of all the major institutions in…the money market. When I used to teach monetary economics at the Ph.d. level, I made all of the students read this entire book (in an earlier and slightly shorter edition) and I quizzed them on every chapter. This was considered highly unorthodox at the time and of course 1200 pages is a lot of opportunity cost. Still, I think it was one of the better educational decisions I have made as a professor and now I view it as somewhat vindicated. The book is not perfect but it is a very good place to start. It is also useful as a source of reference.

Assorted links

1. Jeff Hummel blames Bernanke and Paulson for what has happened. I don’t agree but we are committed to passing along many different points of view.

2. My favorite Greg Mankiw column so far.

3. Dividends vs. share repurchases: an excellent post.

4. New blog on cognition and culture, via Razib.

The credit crunch: I still cannot agree with Alex and Bryan

Alex is a very good truth-tracker but on credit I remain stubborn in my belief that there is a credit crunch. Here is one report:

How is trade finance coping with the credit crunch

Badly. Steve Rodley, director of London-based shipping hedge-fund Global Maritime Investments, puts it bluntly: "The whole shipping market has crashed." The trouble is that credit is the lifeblood of commerce, but it is built entirely on trust. And that has evaporated. As such, many ship owners can’t get banks to issue letters of credit, particularly on cargoes of price-volatile commodities that no longer look like adequate collateral. Even those who can get letters of credit are finding that their counterparties may no longer trust the credit rating of anything other than large, well-established banks, many of which are now charging big premiums. Letters now cost three times the going rate of a year ago, according to Lynn.

Here is another report. Here are other reports. Or read this account:

What’s more, the dollar-denominated trade finance lines that exporter companies rely upon to do business are drying up in dramatic fashion amid the global credit crunch. In Brazil — the world’s top exporter of beef, iron ore, sugar and coffee and the No. 2 exporter of soy — total outstanding trade lines have fallen by half this month to around $18 billion.

Here are simple and in my view decisive quantitative indicators of the current domestic credit crisis. Or here is another report:

According to experts interviewed by Bloomberg, "letters of credit and the credit lines for trade currently are frozen," and as a result, "nothing is moving".

Or here is a recent survey of U.S. retailing CFOs:

Some 41 percent of US retailers are seeing tight credit as a result of

the crisis in the banking sector, and many will cut staff and reduce

buying as a result…

Many other surveys paint a similar picture. I can only repeat my earlier words that immediate credit flows are demand-driven and they do not measure bad credit conditions concurrently because they stem from prior bank commitments. To suggest, as commentator Tom does (and Alex endorses), that we have no credit crisis until lines of credit are exhausted, is in my view sheer logomachy (I like that word). Nor is my view "convenient" or unfalsifiable as was suggested. Here is Wikipedia on lagging indicators and yes it tells you that standard forms of credit fall into this category and this has been understood for some time. Look instead at the currently informative pieces of the evidence and you will see that they point in a very consistent direction.

It is true that many credit channels have not shut down. But the ones

that are shutting down are enough to cause a severe global recession.

Addendum: I added this comment to the discussion: "People, financial markets and financial institutions around the world

are falling apart. I’m not pulling this stuff out of a hat or from a

few crazy journalists. There is massive disintermediation going on

right now, much of it in the shadow banking system. I am trying not to

be dogmatic but it is hard for me to see on what grounds anyone would

deny this."

What did Alan Greenspan concede?

From all the hullabaloo I thought he had granted the death of capitalism but no. Here are his prepared remarks. Here is part of the Q&A.

He did admit that risk models had failed by selectively overweighting periods of euphoria and that the credit default swaps market had exploded in our face. He also knows that there are hundreds of trillions of dollars in open positions in other derivative markets and most of them have worked relatively well in this crisis; his words indicated as such. He also stressed that capitalism has had a string of forty years of numerous successes and that recent experience is an outlier. He is still not sure what to make of the current failure.

Greenspan also said: “Whatever regulatory changes are made, they will pale in comparison to

the change already evident in today’s markets,” he said. “Those markets

for an indefinite future will be far more restrained than would any

currently contemplated new regulatory regime.”

His policy recommendation was the modest one of requiring banks to keep a share in any mortgage.

I don’t agree with all of his detailed points (e.g., too much emphasis on subprime securitization), but I thought the overall ideological "flavor" of his remarks was essentially correct. For differing, and yet not totally different, point of view, here is John Quiggin on Greenspan. Here is the Ayn Rand Center on Greenspan.

Five weeks

Five weeks after the government launched an unprecedented bailout to

save the private company from bankruptcy, AIG has so far burned through

$90.3 billion of government credit.

How many weeks are in a year? Fortunately crude extrapolation is not always the best way of making an estimate, but it still seems this problem is not yet under control. The change in ownership has not brought superior results.

The article, by the way, details how Treasury may spend money on other insurance companies too.

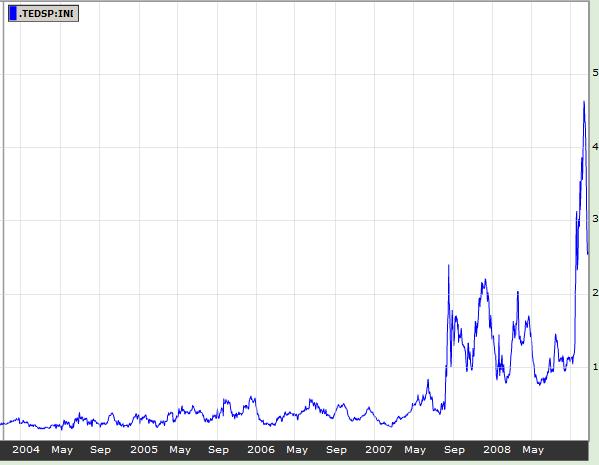

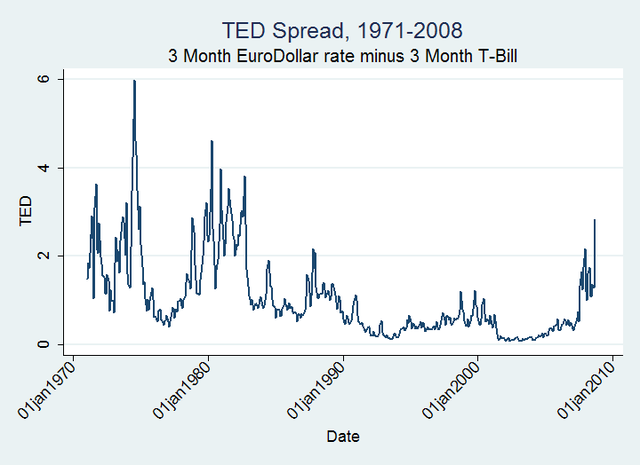

The Long Term Perspective on the TED Spread

Here is the usual picture of the TED spread from Bloomberg.

I was curious to see a longer-term picture so I collected data on the 3 month Treasury bill rate (TB3MS from the St. Louis Fed.) and the 3-month Eurodollar rate (EDM3 from the Fed.) Note that this is current up to September. Also this is slightly different from calculations elsewhere because it’s on a monthly basis, so some daily jumps are smoothed out, and sometimes a different LIBOR rate seems to be used for the ED rate but the different versions appear to correlate well. The advantage of using these measures is that you can get a much longer time series. Here it is (click to expand if unclear).

Economic notes from underground

Daniel Klein has a new project:

The prospective symposium will consist of confessional essays by economists about their existence as economists. Only genuine narrative and sincere reflection are welcome. However, essays may be anonymous.

The impetus of the symposium is to provide an outlet for exploring preference falsification and other forms of moral or intellectual compromise within the economics profession. Authors are encouraged to be introspective and personal, and yet impartial. The purpose of each essay should be to share experiences that speak to situations to which many can relate. We seek biographical essays that will help others understand widely shared problems.

In his or her essay, the author should clarify the kind of preference falsification in which he or she has engaged.

Some consensus

Mark Thoma gives us eight credit series from the St. Louis Fed. He is somewhat surprised to discover that all show positive growth over last year. I think most people who have heard talk of the credit crunch would also find this surprising. Let’s be clear, however, almost all the series also show declining growth. Let’s also be clear that the financial sector is a huge mess. Furthermore, we are in a recession that is likely to get worse especially because growth is declining around the world.

How to get people to vote

KAHNEMAN: …there are

those effects that are small at the margin that can change election

results.You call and ask people ahead of time, "Will you vote?". That’s all.

"Do you intend to vote?". That increases voting participation

substantially, and you can measure it. It’s a completely trivial

manipulation, but saying ‘Yes’ to a stranger, "I will vote" …MYHRVOLD: But to Elon’s point, suppose you had the choice of calling up

and saying, "Are you going to vote?", so you prime them to vote, versus

exhorting them to vote.KAHNEMAN: The prime could very well work better than the exhortation

because exhortation is going to induce resistance, whereas the prime‚ the mild embarrassment causes you to make what feels like a

commitment, and the commitment, if it’s sufficiently precise, is going

to have an effect on behavior.THALER: If you ask them when they’re going to vote, and how they’re going to get there, that increases voting.

KAHNEMAN: And where.

Here is the whole dialogue, on the importance of the environment and priming effects for human psychology; it is very interesting throughout. I thank Stephen Morrow for the pointer.

So how do you get some people not to vote?

Credit as an option

I think of credit as not just a current period flow but also as an option; this is implicit in many of Fischer Black’s pieces, including "Banking and Interest Rates in a World Without Money." If you lose the option to borrow that is a credit crunch too. As for the current financial crisis, my view of the data is that many borrowers have been drawing on their pre-existing lines of credit like crazy, for fear that their chances to borrow may be drying up. Banks have felt liquidity squeezed, in part because of pending CDS settlements, in part because so many borrowers are exercising their borrowing options, and in part because of potential insolvency. That liquidity scramble is why we have been seeing such a huge TED spread and near-zero nominal rates on T-Bills. Even now it remains unclear whether these options will be replenished and of course if they are not that means trouble.

The collapse of "borrowing as an option" shows up in market prices and it also shows up in many anecdotes, as chronicled at calculatedrisk.blogspot.com. It does not necessarily show up in current period credit flow data and in fact it may show up counterintuitively as a spike in borrowing.

I am puzzled by Alex’s admission that there is a recession; no matter which way you assign the causality, doesn’t that mean credit should be contracting? Working within the confines of his own view, shouldn’t Alex be worried that credit flows remain so high?

I believe if we had an explicit series measuring the borrowing option. and its recent collapse, it would show the credit crisis very clearly. In the meantime that crisis does show up in other pieces of information.

Addendum: Here is comment from Mark Thoma and also Felix Salmon.

Godwit fact of the day

The bar-tailed godwit, a plump shorebird with a recurved bill, has

blown the record for nonstop, muscle-powered flight right out of the

sky.A study being published today reports that godwits can fly as many

as 7,242 miles without stopping in their annual fall migration from

Alaska to New Zealand. The previous record, set by eastern curlews, was

a 4,000-mile trip from eastern Australia to China.The birds flew for five to nine days without rest, a few landing on

South Pacific islands before resuming their trips, which were monitored

by satellite in 2006 and 2007.

Here is the full story.

Four Myths of the Credit Crisis, Again

Contra Tyler (see below) neither the post from Free Exchange nor Mark Thoma’s comments "rebutting" the Minn. Fed study, Four Myths About the Financial Crisis of 2008, are compelling or well thought out. The Minn. Fed. presented data demonstrating that four widely reported claims about the credit crisis panic are myths – do either of the cited links claim that any of these myths are in fact true? No. Do either of the cited links present any data at all on the quantity of credit? No. Many people cite prices/rates/spreads as evidence for the crisis but what we ultimately care about is quantity not price. The Fed. piece had lots of data on the quantity of credit. Where is the rebuttal? Does Tyler cite any data at all or lay out his counter-claims? No.

Consider the major item that these links suggest as evidence of the crisis. Amazingly, it’s "an unusual spike in bank lending during the

crisis period." That’s right, an increase in bank lending is evidence of the crisis. The argument is that lack of credit elsewhere means that firms are drawing on their line of credit at banks. One problem with this is that Paul Krugman made this argument way back in February when I said that the lack of credit was being overblown. Thus the "crisis period" keeps changing. In February, the crisis was in February, now Thoma is saying it’s just the last few weeks. More fundamentally, the whole point of a line of credit is to keep credit flowing when one source dries up. A commentator at Thoma’s site nails this one:

Saying that credit availability is so ‘severely’ endangered that

borrowers are forced to utilize credit from banks isn’t the most

persuasive argument. What next?"Gasoline supplies had withered to the point that I was forced to fill up at Texaco instead of Chevron!"

Finally, Tyler and both of the cited pieces attack a stupid claim that obviously neither I nor the Minn. Fed. piece made, namely that the interventions by the Fed. have had no effect. Obviously, they have. But the story the media and the commentariat are reporting is that there is a credit crunch, credit is frozen, firms are starved for credit, we are on the verge of a Great Depression etc. The story has not been, ‘despite some problems in the banking sector quick action by the Federal Reserve and plenty of alternative non-bank credit has insured that credit continues to flow to nonfinancial firms.’

Is there a credit crunch?

Here is a good piece rebutting the Minneapolis Fed study. One point made is this:

…there is the inconvenient matter that the Federal Reserve and

the Treasury went out and did all that stuff they did in order to prevent a

massive breakdown in lending to the real economy. … Now this does

allow sceptics to say, "Well, how do we know things would have collapsed"? We

don’t, of course, but that doesn’t change the fact that current lending takes

into account massive government intervention to make sure that lending

continued. The latter therefore can’t be used to argue that the former wasn’t

necessary.

On these questions I am more of a pessimist than is Alex.

Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics

That’s the title of the new book by Yasheng Huang. This very serious work reexamines the role of the state in the Chinese economy. It suggests that the Chinese private sector has been more productive than claimed, China fits the traditional theory of property rights and incentives more than is often realized, the Chinese economy is not necessarily getting freer, market ideas are strongest in rural China, rural China was reregulated in an undesirable way starting in the early 1990s, the "Shanghai miracle" is overrated, when you calculate the size of the private sector in China it matters a great deal whether you use input or output measures, and China may collapse into crony capitalism rather than following the previous lead of Korea and Japan.

The dissection of Joseph Stiglitz on China, starting on p.68, is remarkable.

I do not have the detailed knowledge to evaluate all of these claims but in each case the author offers serious evidence and arguments. This book does not make for light reading (though it is clearly written), but it is quite possibly the most important economics so far this year. Here is a good review from The Economist.