Month: May 2023

Mississippi Learning

In 2002, Florida adopted a phonics based reading strategy due to Charlie Crist. Scores started to rise. Other southern states started to following suit, including Mississippi long deried as the worst in the nation.

APNews: Mississippi went from being ranked the second-worst state in 2013 for fourth-grade reading to 21st in 2022. Louisiana and Alabama, meanwhile, were among only three states to see modest gains in fourth-grade reading during the pandemic, which saw massive learning setbacks in most other states.

The turnaround in these three states has grabbed the attention of educators nationally, showing rapid progress is possible anywhere, even in areas that have struggled for decades with poverty and dismal literacy rates. The states have passed laws adopting similar reforms that emphasize phonics and early screenings for struggling kids.

“In this region, we have decided to go big,” said Burk, now a senior policy fellow at ExcelinEd, a national advocacy group.

These Deep South states were not the first to pass major literacy laws; in fact, much of Mississippi’s legislation was based on a 2002 law in Florida that saw the Sunshine State achieve some of the country’s highest reading scores. The states also still have far to go to make sure every child can read.

But the country has taken notice of what some have called the Mississippi miracle.

Addendum: See my previous posts on the closely related issue of Direct Instruction.

Population and Welfare: The Greatest Good for the Greatest Number

That is a new paper by Peter J. Klenow, Charles I. Jones, Mark Bils, and Mohamad Adhami, reject its implications at your peril:

Economic growth is typically measured in per capita terms. But social welfare should arguably include the number of people as well as their standard of living. We decompose social welfare growth — measured in consumptionequivalent units — into contributions from rising population and rising per capita consumption. Because of diminishing marginal utility of consumption, population growth is scaled up by a value-of-life factor that substantially exceeds one and empirically averages around 2.7 across countries and over time. Population increases are therefore consistently the dominant contributor, and consumption-equivalent welfare growth around the world averages more than 6% per year since 1960, as opposed to 2% per year for consumption growth. Countries such as Mexico and South Africa rise sharply in the growth rankings once population growth is incorporated, whereas China, Germany and Japan plummet. We show the robustness of these results to incorporating parental time use and fertility decisions using data from the U.S., the Netherlands, Japan, and South Korea. The effects of falling parental utility from having fewer kids are roughly offset by increases in the “quality” of kids associated with rising time investment per child.

If you worry about fertility rates, do you not have to accept something like this framework? Mexico — underrated!

In general, I think people should visit the high population countries more. For the pointer I thank Oliver Wang.

Attack monopoly power with deregulation

One recent study shows just how important regulation is in contributing to monopoly. Since 1970, increased regulation can explain 31% to 37% of the subsequent increase in market power.

Upon reflection, it is obvious that larger firms are better able to deal with regulatory burdens. They have more employees, bigger legal departments and are better suited to deal with governments. Startups are generally leaner and more nimble, but these aren’t necessarily advantages in dealing with Washington or state and local agencies. As regulatory costs rise, the comparative advantage shifts to the larger firms — exacerbating market power problems…

According to researcher Shikhar Singla, regulation costs an average of $9,093 per employee for a typical small firm, compared to $5,246 for a large firm. It is no surprise that, according to the data, smaller firms invest relatively less in more highly regulated areas.

Based on a study of regulatory comments, Singla also found that large firms oppose regulation in general, but push for regulation when such rules and laws damage the interests of smaller firms. Singla also finds that regulatory costs have increased significantly since the late 1990s.

Here is the full Bloomberg column.

Yes, automated tipping is out of control

Consumers already contending with a squeeze on their bank accounts due to inflation are now facing more pressure as businesses introduce new tipping features at self-checkout machines.

Companies, including airports, bakeries, coffee shops and sports stadiums, have now introduced the self-serve tipping option, where customers can leave tips including the typical 20%, despite facing minimal to no interaction with any employee, according to a recent report by The Wall Street Journal…

William Michael Lynn, a consumer behavior and tip culture professor at Cornell University’s Nolan School of Hotel Administration, told the newspaper that businesses “are taking advantage of an opportunity,” and “who wouldn’t want to get extra money at very little cost if you could?”

Here is the story, here is my earlier Bloomberg column on tipping. Just hand cash directly to individual humans who have helped you! Via Anecdotal.

Thursday assorted links

1. Transformers in time series: a survey.

2. AIs learning how to bargain.

3. The Long Now Foundation seeks new executive director.

4. Boettke and Coyne on developments in Austrian economics.

5. “When everyone can sound intelligent, elite conversations will become less intelligible.”

Claims about atheists

The group that is most likely to contact a public official? Atheists.

The group that puts up political signs at the highest rates? Atheists.

HALF of atheists report giving to a candidate or campaign in the 2020 presidential election cycle.

And while they don’t lead the pack when it comes to attending a local political meeting, they only trail Hindus by four percentage points.

…atheists take part in plenty of political actions – 1.52 to be exact. The overall average in the entire sample was .91 activities. The average atheist is about 65% more politically engaged than the average American.

And this:

The results here are clear and unambiguous – atheists are more likely to engage in political activities at every level of education compared to Protestants, Catholics or Jews. For instance, an atheist with a high school diploma reports .7 activities, that’s at least .2 higher than any other religious group.

Political engagement is clearly related to education, though. The more educated one is, the more likely they are to be politically active. But at every step of the education scale, atheists lead the way. Sometimes those gaps are incredibly large. A college educated atheist engages in 1.7 activities, it’s only 1.05 activities for a college educated evangelical.

From Ryan Burge, here is the full data analysis.

My Conversation with Simon Johnson

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode description:

What’s more intense than leading the IMF during a financial crisis? For Simon Johnson, it was co-authoring a book with fellow economist (and past guest) Daron Acemoglu. Written in six months, their book Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, argues that widespread prosperity is not the natural consequence of technological progress, but instead only happens when there is a conscious effort to bend the direction and gains from technological advances away from the elite.

Tyler and Simon discuss the ideas in the book and on Simon’s earlier work on finance and banking, including at what size a US bank is small enough to fail, the future of deposit insurance, when we’ll see a central bank digital currency, his top proposal for reforming the IMF, how quickly the Industrial Revolution led to widespread prosperity, whether AI will boost wages, how he changed his mind on the Middle Ages, the key difference in outlook between him and Daron, how he thinks institutions affect growth, how to fix northern England’s economic climate, whether the UK should join NAFTA, improving science policy, the Simon Johnson production function, whether MBAs are overrated, the importance of communication, and more.

And here is one excerpt:

COWEN: If institutions are the key to economic growth, as many people have argued — Daron and yourself to varying degrees — why, then, is prospective economic growth so hard to predict?

In 1960, few people thought South Korea would be the big winner. It looked like their institutions were not that good. It was a common view: oh, Philippines, Sri Lanka — then Ceylon — would do quite well. They had English language to some extent. They seemed to have okay education. And those two nations have more or less flopped. South Korea took off. It’s now, per capita income roughly equal to France or Japan. Doesn’t that mean it’s not about institutions? Because institutions are pretty sticky.

JOHNSON: Yes, I think of institutions as being part of the hysteresis effect, if you can get it in a positive way, that if you grow and you strengthen institutions, which South Korea has done, it makes it much harder to relapse. There are plenty of countries that had spurts of growth without strong institutions and found it hard to sustain that.

You make a very good point about the early 1960s, Tyler. There wasn’t that much discussion that I’ve seen about institutions per se, but education — yes, absolutely. Culture — people made the same comparisons. They said, “Confucian culture is no good or won’t lead to growth. That’s a problem, for example, for South Korea.” That turned out to be wrong.

I think institutions are sticky. I think history matters a lot for them. They’re not predestination, though. You could absolutely carve your own way, but the carve-your-own way is harder when you start with institutions that are more problematic, less democratic, more autocratic control, less protection of property rights.

All of these things can go massively wrong, but building better institutions and making them sustainable, like Eastern Europe — the parts of the former Soviet Empire that managed to escape the Soviet influence after 1989, 1991 — I think those countries have worked long and hard, with very mixed results in some places, to build better institutions. And the EU has helped them in that regard, unquestionably.

I enjoyed this session with Simon.

*Russia and China*

Authored by Philip Snow, the subtitle is Four Centuries of Conflict and Concord. This book is excellent and definitive and serves up plenty of economic history, here is one bit from the opening section:

The trade nonetheless went ahead with surprising placidity. Now and again there ere small incidents in the form of cattle-rustling or border raids. In 1742 some Russians were reported to have crossed the frontier in search of fuel, and in 1744 two drunken Russians killed two Chinese traders in a squabble over vodka.

I am looking forward to reading the rest, you can buy it here.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Toronto anti-capitalist cafe is closing. I guess capitalism was worse than they thought (better than I thought?).

2. Brazilian Portuguese edition of Talent is out, Talento, with Daniel Gross.

3. New George Tavlas book on the history of monetarism.

4. Gorton and Zhang on bank runs and crypto.

5. Can data keep people out of prison? Steve Levitt podcast with Clementine Jacoby of Recidivez.

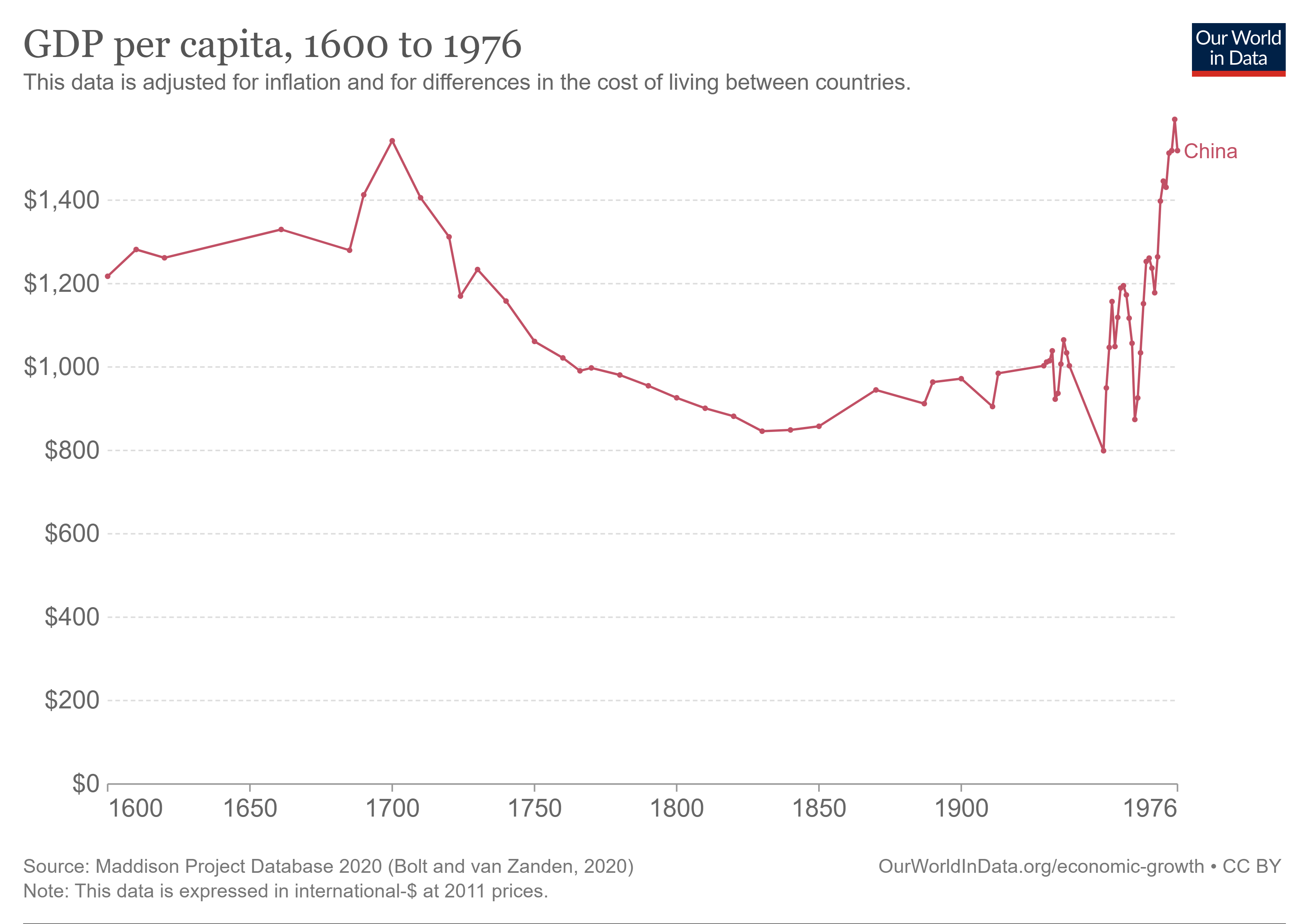

Graph of the Day

A remarkable graph pointed to by Phil Magness who writes:

China’s GDP per capita hit its lowest point in the past 300 years under Maoism. Twice.

The first time was during the civil war and the second was the Great Leap Forward. Wojtek Kopczuk comments:

Even taking into account that these historical measurements are notoriously problematic and difficult to make comparable, the fact that it is even in the ballpark is shocking.

Mexico fact of the day

In 2022 almost double the number of Mexicans reported having money extorted than did five years before (see chart). Only a tiny minority report.

From The Economist, here is more:

The big money comes, however, from “taxing” businesses in sectors such as agriculture and mining. Avocados, Mexico’s “green gold”, are a good example. The country provides almost a third of global supply, most of which is grown in the western state of Michoacán. The $3bn-worth of them exported every year to the United States is a huge source of income for the producers and also for gangs. For the past three years Erick Rodríguez, a farmer, has paid an annual “fee” of 10,000 pesos ($560) per hectare to Familia Michoacana, a local criminal group. Mr Rodríguez (not his real name) says the gang comes with data about the size of his farm and tells him to hold back stock to push up prices. Ms Felbab-Brown’s fieldwork in Mexico shows how gangs also force fishermen to sell their catch at a cut price, which they then sell for a profit to restaurants. They also dictate the terms of when and what they can fish.

I suppose the optimistic take is that if this ever can be stopped, Mexican economic growth will be especially high?

The Re-Emerging Suicide Crisis in the U.S.

The suicide rate in the United States has risen nearly 40 percent since 2000. This increase is puzzling because suicide rates had been falling for decades at the end of the 20th Century. In this paper, we review important facts about the changing rate of suicide. General trends miss the story of important differences across groups – suicide rates rose substantially among middle aged persons between 2005 and 2015 but have fallen since. Among young people, suicide rates began a rapid rise after 2010 that has not abated. We review empirical evidence to assess potential causes for recent changes in suicide rates. The economic hardship caused by the Great Recession played an important role in rising suicide among prime-aged Americans. We illustrate that the increase in the prevalence of depression among young people during the 2010s was so large it could explain nearly all the increase in suicide mortality among those under 25. Bullying victimization of LGBTQ youth could also account for part of the rise in suicide. The evidence that access to firearms or opioids are major drivers of recent suicide trends is less clear. We end by summarizing evidence on the most promising policies to reduce suicide mortality.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Dave E. Marcotte and Benjamin Hansen.

What should I ask Stephen Jennings?

I will be doing a Conversation with him:

Stephen Jennings is the Founder & CEO of Rendeavour, Africa’s largest urban developer, with over 12,000 hectares (30,000 acres) of satellite city developments near high-growth cities in Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, Zambia and Democratic Republic of Congo.

Link here. I also know Stephen from his time working on reforms in New Zealand, way back when in the early 1990s. Here are various links about Stephen. So what should I ask?

Tuesday assorted links

1. To what extent can they pull your DNA from thin air? (NYT)

2. Accounting for chores, Americans have as much leisure time as do Swedes.

3. John Cochrane on Bob Lucas. And David Henderson on Bob Lucas (WSJ).

5. Daron Acemoglu on Turkey and the election.

6. Ezra Klein and Veronique de Rugy podcast, covering the debt ceiling (NYT).

7. Soon your iPhone will be able to speak in your own voice.

My tribute to Robert E. Lucas

For Bloomberg, here is one bit:

Lucas’s primary contribution was to insist that all assumptions about expectations be spelled out and tested to see if they were consistent with all other parts of the argument. For instance, if you wanted to assert that people would respond to one set of government actions but not another, you had to outline why that might be the case. In retrospect it seems simple, but Lucas (with co-authors, notably Nancy Stokey) was the person who showed how to do it. The end result was a reworking of virtually everyone’s macroeconomic arguments — monetarist, Keynesian or otherwise.

And this:

I recall Lucas giving a seminar at Harvard in 1984, during my graduate studies there. With his no-nonsense manner and dark suit, he reminded me of a character from a Chicago gangster movie. Yet he was also charming, in part because he could see so quickly where every argument or critical point was headed. Many of the graduate students showed up with a hostile attitude, protective of their more Keynesian approaches and convinced they could expose the simplistic assumptions of Lucas’s models. Ninety minutes later, it was clear that those assumptions were not so vulnerable after all.

Lucas survived that encounter unscathed, and perhaps made a few converts too. He will be missed, but his ideas and arguments will continue to thrive.

Recommended.