Category: Data Source

Is the middle class shrinking?

From the excellent Scott Winship:

Krueger’s claim of a shrinking middle class relies on the same peculiar definition. Specifically, “middle class” is defined as having a household income at least half of median income but no more than 1.5 times the median. I re-ran the numbers using the same definition and data source as Krueger and found that the entire reason the middle class has “shrunk” is that more households today have incomes that put them above middle class. That’s right, the share of households with income that puts them in the middle class or higher was 76 percent in 1970 and 75 percent in 2010—two figures that are statistically indistinguishable. For that matter, I am not discovering fire here; Third Way made the same point in early 2007 (page 7). A shrinking middle class is only a problem if it reflects fewer people reaching the middle class.

The post is excellent throughout and it contains many more points of interest.

Not Catching Up: Affirmative Action at Duke University

A working paper titled What Happens After Enrollment: An Analysis of the Time Paths of Racial Difference in GPA and Major Choice by Duke university economists Peter Arcidiacono and Esteban Aucejo and sociologist Ken Spenner is creating a stir. The authors track a sample of Duke students from admissions to graduation in order to determine the effects of affirmative action.

Under one theory of affirmative action the goal is to give minority students an opportunity to catch-up to their peers once everyone is given access to the same quality of schooling. On a first-pass through the data, the authors find some support for catch-up at Duke. In year one, for example, the median GPA of a white student is 3.38, significantly higher than the black median GPA of 2.88. By year four, however, the differences have shrunk to 3.64 and 3.31 respectively.

Further analysis of the data, however, reveal some troubling issues. Most importantly, the authors find that all of the shrinking of the black-white gap can be explained by a shrinking variance of GPA over time (so GPA scores compress but class rankings remain as wide as ever) and by a very large movement of blacks from the natural sciences, engineering and economics to the humanities and the social sciences. It’s well known that grade inflation is higher in the humanities and the social sciences so the shift in college major can easily explain the shrinking black-white gap in GPA. (The authors show that grades are higher in the humanities holding SAT scores constant and also that students themselves report that classes in the sci/eng/econ are harder than classes in the humanities and that they study more for these classes).

The shift of black students across majors is dramatic. Prior to entering Duke, for example, 76.7% of black males expect to major in the natural sciences, engineering or economics but only 35% of them actually do major in these fields (almost all Duke students do graduate so this result is due to a shift in major not dropping out). In comparison, 68.7% of white males expect to major in sci/eng/econ and 63.6% of them actually do graduate with a major in these fields (this is from Table 9 and is of those students who had an expected major). White and black females also exit sci/eng/econ majors at high rates, although the race gap for females is not as large as for males. The authors do not discuss the consequences of dashed expectations.

An important finding is that the shift in major appear to be driven almost entirely by incoming SAT scores and the strength of the student’s high school curriculum. In other words, blacks and whites with similar academic backgrounds shift away from science, engineering and economics and towards the easier courses at similar rates.

I have argued that the United States would benefit from more majors in STEM fields but that is not the point of this paper. The point is that there is no evidence for catch-up at Duke and thus to the extent that affirmative action can work in that way it may have to occur much earlier.

Hat tip: Newmark’s Door.

Structurally impaired jobs vs. non-impaired jobs

Here is some text from the post:

One way to look at the US job market is to break it up into two components: jobs generated by structurally “impaired” and “non-impaired” sectors. Credit Suisse defines structurally impaired sectors to “include real estate related industries, finance, manufacturing, and the state and local government sector.” These are the sectors that at least in part rode the “bubble” economy wave. Many of these jobs were credit dependent, with growth beyond what the economy could sustain naturally.

The chart below shows the job creation and loss of the two components. The structurally impaired sector jobs created during the period of over-capacity growth simply never returned. The sectors were highly credit dependent and with all the deleveraging taking place, the jobs are not likely to come back any time soon…

On the other hand job growth of the non-impaired sectors has almost returned to the pre-crisis levels.

Could it be that 2011 is what macroeconomic recovery looks like, minus the remaining structural problems? Hat tip goes to FT Alphaville for the pointer, and here is my earlier post on the disaggregated aggregate demand.

The culture that is Norway?

The UK’s 2011 bestseller lists might have been dominated by cookery, courtesy of Jamie Oliver, and romance, courtesy of David Nicholls, but Norwegian readers were plumping for another sort of book last year: the Bible.

The first Norwegian translation of the Bible for 30 years topped the country’s book charts almost every week between its publication in October and the end of the year, selling almost 80,000 copies so far and hugely exceeding expectations. Its launch in the autumn saw Harry Potter-style overnight queues, with bookshops selling out on the first day as Norwegians rushed to get their hands on the new edition.

I’ve been wondering what the new religion of Europe (is Norway Europe?) is going to be. The article is here.

Who are the most searched-for economists?

The list is here, and #1 not surprisingly is Paul Krugman. Singh and Draghi are second and third respectively, followed by Bernanke and Sen. I am pleased to have come in at #26.

For the pointer I thank David Friedman.

Scott Winship on mobility in America

On net, it seems it is not going down and may be rising:

…consider what we know from previous studies of trends in intergenerational income mobility. The bulk of the existing research shows either that mobility has increased over the long run or that it has changed little in either direction. That includes both studies that I know of examining changes in upward mobility from the bottom. It also includes six studies using measures of mobility not confined to movement up from the bottom; these find either no change or rising mobility. In contrast, only two papers find a fall in mobility, each using non-directional measures. Notably, one of them shows an uptick in the mobility of the most recent two birth cohorts it examined, leaving in doubt the question of whether the longer-term decline it found would have persisted had the authors had more recent data. The other study finds somewhat mixed evidence, depending on the data source and whether children of single parents are included.

Of course this doesn’t mean mobility is “high enough.” Scott also will be publishing a more detailed explication of these results with Brookings.

The new Robert Gordon paper on productivity

Via Reihan, here is the abstract and paper:

This paper provides three perspectives on long-run growth rates of labor productivity (LP) and of multi-factor productivity (MFP) for the U. S. economy. It extracts statistical growth trends for labor productivity from quarterly data for the total economy going back to 1952, provides new estimates of MFP growth extending back to 1891, and tackles the problem of forecasting LP and MFP twenty years into the future.

The statistical trend for growth in total economy LP ranged from 2.75 percent in early 1962 down to 1.25 percent in late 1979 and recovered to 2.45 percent in 2002. Our results on productivity trends identify a problem in the interpretation of the 2008-09 recession and conclude that at present statistical trends cannot be extended past 2007. For the longer stretch of history back to 1891, the paper provides numerous corrections to the growth of labor quality and to capital quantity and quality, leading to significant rearrangements of the growth pattern of MFP, generally lowering the unadjusted MFP growth rates during 1928-50 and raising them after 1950. Nevertheless, by far the most rapid MFP growth in U. S. history occurred in 1928-50, a phenomenon that I have previously dubbed the “one big wave.”

The paper approaches the task of forecasting 20 years into the future by extracting relevant precedents from the growth in labor productivity and in MFP over the last seven years, the last 20 years, and the last 116 years. Its conclusion is that over the next 20 years (2007-2027) growth in real potential GDP will be 2.4 percent (the same as in 2000-07), growth in total economy labor productivity will be 1.7 percent, and growth in the more familiar concept of NFPB sector labor productivity will be 2.05 percent. The implied forecast 1.50 percent growth rate of per-capita real GDP falls far short of the historical achievement of 2.17 percent between 1929 and 2007 and represents the slowest growth of the measured American standard of living over any two-decade interval recorded since the inauguration of George Washington.

Germany fact of the day (not about the euro, or is it?)

Germany, passengers cars per thousand: 544

United States, passenger cars per thousand: 409

I was surprised. The source is here and for the pointer I thank Axayacatl Maqueda.

Addendum: The “fact” seems to be wrong, see the comments, see also Kevin Drum.

Immigrants, welfare reform, and the U.S. safety net

That is the title of an intriguing new economics paper by Marianne Bitler and Hilary W. Hoynes, official NBER version here. Remember when they cut some benefits for immigrants, circa 1996? That can form the basis for a natural experiment, because non-immigrant poor families did not experience a similar cut in benefits.

I urge extreme caution in the interpretation, but here is one result:

The difference-in-difference estimates show that poverty rates declined for children in immigrant-headed households compared to natives post-welfare reform (2008-2009) relative to pre-reform (1994-1995).

But why? There is more:

This result is unexpected but may be explained by a change in the composition of immigrant children (see Figure 3). That is…the difference-in-difference reflects the decrease in immigrant poverty in the 1994-1999 period.

You can take this as a mix of optimism about immigrants and skepticism about some welfare programs, or perhaps optimism about how a health job market helps immigrants more than non-immigrants. I don’t in Figure 3 see any actual measurement of the composition of immigrants, although immigrant households do show rising income levels over the critical years. Stick by the caution mentioned above. In any case, following the decrease in welfare benefits immigrant households rely more heavily on earned income, which should be taken as good news. I would rather offer fewer benefits to immigrants and take more people in, to the extent that is the choice.

I don’t think this paper gets to the bottom of the puzzle it is studying, but it is an important piece of work.

Economists explain the last year in terms of charts

Here is the lot, much to ponder, there is one from me too but flip through the whole series.

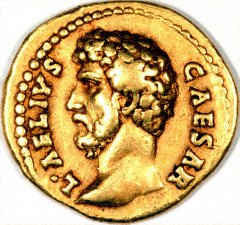

Roman Empire More Equal than the United States

In The Size of the Economy and the Distribution of Income in the Roman Empire, a careful paper published in the Journal of Roman Studies in 2009, Walter Scheidel and Steven Friesen estimate the size and distribution of the Roman economy at its demographic peak around the middle of the 2nd century c.e.

We conclude that in the Roman Empire as a whole, a ‘middling’ sector of somewhere around 6 to 12 per cent

of the population, defined by a real income of between 2.4 and 10 times ‘bare bones’

subsistence or 1 to 4 times ‘respectable’ consumption levels, would have occupied a fairly

narrow middle ground between an élite segment of perhaps 1.5 per cent of the population and a vast majority close to subsistence level of around 90 per cent. In this system, some 1.5 per cent of households controlled 15 to 25 per cent of total income, while close to

10 per cent took in another 15 to 25 per cent, leaving not much more than half of all income for all remaining households.

Thus, in Rome the top 1.5% controlled 15-25% of income while in the United States around 2007 the top 1% controlled 23.5% of income thus suggesting slightly more inequality in the United States. Scheidel and Friesen calculate a Roman Empire gini coefficient of .42-.44 again perhaps slightly less than the U.S. coefficient of around .4-.45 depending on source.

Interestingly, the Roman State did not manage to collect that much:

Given a GDP of somewhere

around HS17–19bn, annual state expenditure of approximately HS900m would have

represented an effective tax rate of approximately 5 per cent of GDP, which is the same as

for France in 1700. This finding confirms Hopkins’s claim that the imperial government

did not capture more than 5 to 7 per cent of GDP and that Roman taxes were fairly low.

The overall public sector share of GDP was somewhat larger depending on the scale of

municipal spending, while the overall nominal tax rate had to be higher still in order to

accommodate taxpayer non-compliance, tax amnesties, and rent-seeking behaviour by

tax-collectors and other intermediaries. Moreover, we must not forget that Italy’s immunity from output and poll taxes required the public sector share in the provinces to exceed

the empire-wide average. These various adjustments allow us to reconcile our GDP estimate with reported nominal taxes of around 10 per cent of farm output on private land

reported in Roman Egypt and somewhat higher rates in less developed regions where

enforcement may have been more difficult.

(Thus, despite the aqueducts Rome may not have done that much for the people after all.)

Hat tip to Tim De Chant at Per Square Mile who has further discussion.

British STEM

In my book (Amzn, Nook, iTunes) I discuss the stagnation of STEM majors in the United States. According to a new report something similar, although somewhat less pronounced, has been happening in Britain over the last decade:

In fact, overseas students accounted for more than 100 per cent of the increase in student numbers between 1996/97 and 2006/07 in engineering and technology. This means the total number of British engineering and technology students fell during the period.

TGS for Britain

Britons will be worse off in 2015 than they were in 2002 as the nation grapples with a severe squeeze on living standards, the Institute for Fiscal Studies said on Wednesday.

Slow income growth before the downturn, the depth of the recession and the sluggishness of the recovery have combined to create easily the longest period of stagnation in real incomes since records began in 1961.

That is from the FT, via Michael Rosenwald.

Melissa Dell on trafficking networks and the Mexican drug war

This is the abstract, from a very smart and brave woman:

Drug trade-related violence has escalated dramatically in Mexico during the past five years, claiming 40,000 lives and raising concerns about the capacity of the Mexican state to monopolize violence. This study examines how drug traffickers’ economic objectives influence the direct and spillover effects of Mexican policy towards the drug trade. By exploiting variation from close mayoral elections and a network model of drug trafficking, the study develops three sets of results. First, regression discontinuity estimates show that drug trade-related violence in a municipality increases substantially after the close election of a mayor from the conservative National Action Party (PAN), which has spearheaded the war on drug trafficking. This violence consists primarily of individuals involved in the drug trade killing each other. The empirical evidence suggests that the violence reflects rival traffickers’ attempts to wrest control of territories after crackdowns initiated by PAN mayors have challenged the incumbent criminals. Second, the study accurately predicts diversion of drug traffic following close PAN victories. It does this by estimating a model of optimal routes for trafficking drugs across the Mexican road network to the U.S. When drug traffic is diverted to other municipalities, drug trade-related violence in these municipalities increases. Moreover, female labor force participation and informal sector wages fall, corroborating qualitative evidence that traffickers extort informal sector producers. Finally, the study uses the trafficking model and estimated spillover effects to examine the allocation of law enforcement resources. Overall, the results demonstrate how traffickers’ economic objectives and constraints imposed by the routes network affect the policy outcomes of the Mexican Drug War.

The link to her papers — all of which look interesting — is here. She is currently on the job market from MIT, and I will be serving up some further posts on a few of the more interesting job market papers this year. The original pointer is from Chris Blattman.

Here is a good summary and discussion from Ray Fisman:

Dell conjectures—based on anecdotal evidence about the drug war—that police efforts tend to weaken a cartel’s grip on a town just enough that competing traffickers see an opening to come in and fight for control of the town. Indeed, when a rival cartel controls a neighboring town, the effect of a PAN win on the drug-related homicide rate is several times higher.

And:

Drug confiscations in the communities where Dell predicts traffickers will relocate to following a crackdown increase by about 20 percent in the months following close PAN victories. It’s a reminder that crime fighting is a bit like Whac-A-Mole—smothering traffickers’ activities in one locale merely causes them to shift their operations elsewhere. Dell finds that drug-related homicides also go up in places that her model predicts will lie on traffickers’ new paths from Mexican drug labs to the U.S. border.

Are CEOs paid their value added?

Remember Paul Krugman’s forays into “the wage reflects what the top earners are really worth” topic, and the surrounding debates? Why should this discussion be such a fact-free zone? Why so little discussion of tax incidence?

Let’s start with the literature.

Read this paper by Kevin Murphy (pdf), especially pp.33-38. Admittedly the paper is from 1999 and it won’t pick up the more recent problems with the financial sector. But most of the data are from plain, ol’ garden variety CEOs. In many of the estimations we see CEOs picking up less than one percent of the value they create for the firm, and all of the estimates of their value capture are impressively small, albeit rising over time. Never is the percentage of value capture anything close to one hundred percent. “One percent value capture” is an entirely plausible belief.

You might think this sounds whacky but it makes theoretical sense. For instance often CEO performance is motivated by equity and options, but few CEOs are wealthy enough to own more than a very small chunk of the company (risk-aversion may be a factor too), and that will mean their pay won’t reflect value created at the margin. It’s a standard result of agency theory, stemming from first principles.

Maybe you’re suspicious of this work but the way these estimates are done is quite straightforward, and results of this kind have not been overturned. You can formulate a “pay isn’t closely enough linked to performance” critique from these investigations, but not a “they’re paid as much as they contribute” conclusion or anything close to that. (And, if it matters, the “conservative” and also WSJ Op-Ed page view has embraced these results for almost two decades, at least since the original Jensen-Murphy JPE piece; Krugman identified the conservative position with the Clarkian perfect competition w = mp stance but that is incorrect.)

You might be thinking “Ha! Burn on Krugman!,” but not so fast. Like Wagner’s music, Krugman’s position here is “better than it sounds,” though not nearly as strong as Krugman would like it to be.

Let’s turn to taxation of the top 0.1 percent, and focus on these CEOs. If the tax rate on their income/K gains goes up, the firm will compensate by giving them more equity/options, to keep them working hard. In other words, the tax rate on the top earners can be hiked without much effect on CEO effort because there is an offset internal to the firm. At some margin the firm’s shareholders will be reluctant to chop off more equity/options to the CEO, but the marginal value created by maintaining the incentive seems to be very high, for reasons presented above, and so the net CEO incentives will be maintained, even in light of new and higher taxes on CEO earnings.

But here’s the problem, if that’s the right word. The incidence of that tax is going to fall on shareholders in general and thus on capital in general. These top CEOs could even get off scot-free, if the shareholders up the equity/options participation of the CEO to offset completely the effects of the new and higher tax rate. This is also relevant to the Piketty-Saez-Stantcheva analysis that everyone has been talking about; they don’t see these mechanisms with sufficient clarity.

Moral of the story: it’s harder to tax the top earners than you think.

The second moral is that tax incidence remains a neglected topic, even among top economists.

The third moral is that too many people, including both Krugman and his critics on this point, have been neglecting the literature.

By the way, other assumptions can be made and other results generated, but I am focusing on one of the core cases.