Category: History

Matthew Bishop’s new book

With Michael Green, In Gold We Trust: The Future of Money in an Age of Uncertainty, Kindle Single. Here is a short video about the book.

From the authors:

It provides a lively analysis of the big economic questions currently facing America, such as the danger to the dollar posed by gridlock in DC, especially over deficit reduction, the euro crisis, the growing risk of inflation and the changing attitude of China towards America. We argue that the renaissance of gold, plus the development of virtual currencies such as Bitcoin, reflect weaknesses in the technology of money that we all need to take seriously and try to fix.

*The Clash of Economic Ideas*

In 1958, on his first visit to India, the Hungarian-British development economist Peter Bauer was eager to meet the Indian economist B.R. Shenoy. Bauer knew the name from a “Note of Dissent on the Memorandum of the Economists’ Panel,” which Shenoy had written criticizing India’s Second five-Year Plan. In 1955 the Indian government had recruited twenty-one senior Indian economists for the Panel of Economists, chaired by the minister of finance, to review the plan. Twenty of the economists had signed a memorandum endorsing the plan. Professor Shenoy was the lone dissenter Shenoy’s “Note of Dissent” was an annoyance to members of the Indian Planning Commission; to Prime Minister Nehru, who had initiated the planning effort; to Nehru’s adviser P.C. Mahalanobis, who had drafted the plan; and even to international aid officials, who overwhelmingly supported the planning effort. Shenoy had become persona non grata in official economic policy-making circles.

Yet Shenoy turned out largely to be right.

That is from the forthcoming excellent book by Lawrence H. White, Amazon link here. The book is not mostly about India, but it is about the role of economic ideas in shaping economic outcomes. The chapter on India is my favorite, however, and it is perhaps the very best place to start to understand the failures of India’s planning period.

White also points our attention to Milton Friedman’s 1955 Memorandum to the Indian Government, which is I believe not well known, not even among Friedman fans.

Corruption and the history of development economics

A few observations, based on some recent reading:

1. It is remarkable how little the topic is discussed in the mainstream literature before the 1990s. Gunnar Myrdal to his credit does discuss it a bit in his Asian Drama.

2. I have seen more than a few articles suggesting Anne Krueger showed that rent-seeking accounted for 7.3 percent of Turkish gdp (in the 1960s). That’s not what Krueger said. Rather she showed that import licenses were equivalent to this value, and that this provided an upper bound for the amount of rent-seeking.

3. The real costs of rent-seeking and corruption are the “limits to technology transfer” argument of Parente and Prescott, not the standard rent-seeking box. That paper alone could bring a Nobel Prize, and yet it’s hardly ever mentioned in assessments of Prescott.

James Stock and Mark Watson on the Great Recession

Binyamin Applebaum summarizes their new paper:

The paper, entitled “Disentangling the Channels of the 2007-2009 Recession,” will be posted on the general conference Web site Thursday afternoon.

The authors argue that the slow pace of recovery reflects a long-term deterioration in economic prospects. Specifically, they estimate that the trend growth rate of gross domestic product fell by 1.2 percentage points between 1965 and 2005.

…the key reason for the faltering pace of growth is that the work force is expanding more slowly. Population growth has slowed, and so has the pace at which women are entering the labor market.

“These demographic changes imply continued low or even declining trend growth rates in employment, which in turn imply that future recessions will be deeper, and will have slower recoveries, than historically has been the case.”

Indeed, recent growth has actually outpaced their expectations.

“The current recovery in employment is actually faster than predicted,” they write. “The puzzle, if there is one, is why the recovery was as strong as it has been.”

This general theory about the power of women has been propounded before, notably by the economist Tyler Cowen in his recent book “The Great Stagnation.”

The paper itself can be found here (pdf). By the way, for market monetarists, equity markets seem to agree. Stock and Watson, of course, are two of the most technically accomplished macroeconometricians. This is further evidence — perhaps the most thorough empirical paper on the topic to date — that the Great Recession has been about the interaction of cyclical and structural forces.

Other interesting papers from that symposium are here, including a DeLong-Summers defense of stimulus as possibly self-financing.

Will Arab Spring lead to democracy?

A new BPEA paper by Eric Chaney (pdf) suggests maybe not:

Will the Arab Spring lead to long-lasting democratic change? To explore this question I examine the determinants of the Arab world’s democratic defi cit in 2010. I find that the percent of a country’s landmass that was conquered by Arab armies following the death of the prophet Muhammad statistically accounts for this defi cit. Using history as a guide, I hypothesize that this pattern reflects the long-run influence of control structures developed under Islamic empires in the pre-modern era and and that the available evidence is consistent with this interpretation. I also investigate the determinants of the recent uprisings. When taken in unison, the results cast doubt on claims that the Arab-Israeli conflict or Arab/Muslim culture are systematic obstacles to democratic change in the region and point instead to the legacy of the region’s historical institutional framework.

Here is a good sentence:

…the fact that the Arab world’s democratic defi cit is shared by 10 non-Arab countries that were conquered by Arab armies casts doubt on the importance of the role of Arab culture in perpetuating the democratic defi cit.

And this:

Once one accounts for the 28 countries conquered by Arab armies, the evolution of democracy in the remaining 15

Muslim-majority countries since 1960 largely mirrors that of the rest of the developing world.

Claude Shannon and juggling

As he turned away from academic pursuits, Shannon also focused on inviting aspects: It was a game, a problem, a puzzle. It produced motions he considered beautiful. And it was something he simply could not master, making it all the more tantalizing. Shannon would often lament that he had small hands, and thus had great difficulty making the jump from four balls to five — a demarcation, some might argue, between a good juggler and a great juggler. Old friends — fellow jugglers from the Bell Labs days — wrote encouraging letters suggesting he was closer to five balls than he realized. It’s likely Shannon never quite achieved that. Nevertheless, in the late 1970s he found himself consumed by the question of whether he could formulate a scientific theory of juggling to explain its unifying principles. Just as he had done years before — for his papers on cryptography, information, and computer chess — he delved into the history of juggling and took stock of its greatest practitioners.

That is from Jon Gertner’s The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation. Here is my previous post on the book, which I recommend highly.

More on the time-dependence of fiscal policy

Chris Reicher has a new paper (pdf) and the abstract is here:

This paper documents the systematic response of postwar U.S. fiscal policy to fiscal imbalances and the business cycle using a multivariate Fiscal Taylor Rule. Adjustments to taxes and purchases both account for a large portion of the fiscal response to debt, while authorities seem reluctant to adjust transfers. As expected, taxes are highly procyclical; purchases are acyclical; and transfers are countercyclical. Neither pattern has changed much over time, except that adjustment happens more slowly after 1981 than before 1980. The role of adjustments to purchases in stabilizing the debt indicates that the recent discussion about spending reversals is highly relevant.

The gated, published version is here. Chris writes me in an email:

Germany uses a similar mix of spending restraint vs. tax increases as the United States in order to consolidate its fiscal position over time. My 2012 article basically corroborates Bohn’s results using different techniques for the postwar period. I have a set of unpublished estimates which indicates the same thing for Germany and a number of other countries–adjustments to real spending and taxes both account for large portions of fiscal authorities’ endogenous response to debt.

Chris points me to a further paper on the topic, forthcoming in ReStat.

*The Idea Factory*

I loved this book and devoured it in a single sitting. The author is Jon Gertner and the subtitle is Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation. Here is one excerpt:

Scientists who worked on radar often quipped that radar won the war, whereas the atomic bomb merely ended it. This was not a minority view. The complexity of the military’s radar project ultimately rivaled that of the Manhattan Project, but with several exceptions. Notably, radar was a far larger investment on the part of the U.S. government, probably amounting to $3 billion as contrasted with $2 billion for the atomic bomb. In addition, radar wasn’t a single kind of device but multiple devices — there were dozens of different models — employing a similar technology that could be used on the ground, on water, or in the air.

One lesson of this book is how much war can spur innovation. Here is one Gertner article on the themes of the book. Here is a review of the book. Anyone interested in the history of science, tech, or innovation should buy and read this book.

Temporary vs. permanent increases in government spending

Not long ago Paul Krugman wrote:

To a first approximation, in other words, the effect of current fiscal policy — whether stimulus or austerity — an [on?] the actions of future governments is zero.

He makes further points at the link, although there is not a citation to the literature. I thought we should look at the evidence a little more closely. Some of it contradicts Krugman as read literally, though it is not all bad news for his larger point.

Here is an abstract from Brian Goff:

In spite of Peacock and Wiseman’s 1961 NBER study demonstrating the “displacement effect”, simplistic theoretical and empirical distinctions between temporary and permanent spending are common. In this paper, impulse response functions from ARMA models as well as Cochrane’s non-parametric method support Peacock and Wiseman’s conclusion by showing 1) government spending in the aggregate displays strong persistence to temporary shocks, 2) simple decomposition methods intended to yield a “temporary” spending series have a weak statistical foundation, and 3) persistence in spending has increased during this century. Also, as a basic “fact” of government spending behavior, the displacement effect lends support to interest group and bureaucracy models of government spending growth.

There is persistence to spending, although this study does not create a category for stimulus spending per se, however that concept might be defined. The work of Robert Higgs also provides a clear look at ratchet effects on government spending, control, and regulation, although Higgs focuses on war rather than spending. State governments also seem to exhibit a ratchet effect, whereby good times bring about permanently higher budgetary demands, if only through endowment effects, lock-in, and status quo bias.

That said, the federal debt/gdp ratio seems to show mean reversion, as does the measure of primary surplus. That would mean that fiscally troubled situations are followed by improvements, though not necessarily from spending decreases. In fact there has been considerable reliance on a “growth dividend.” And here is Henning Bohn from the QJE:

How do governments react to the accumulation of debt? Do they take corrective measures, or do they let the debt grow? Whereas standard time series tests cannot reject a unit root in the U. S. debt-GDP ratio, this paper provides evidence of corrective action: the U. S. primary surplus is an increasing function of the debt-GDP ratio. The debt-GDP ratio displays mean-reversion if one controls for war-time spending and for cyclical fluctuations. The positive response of the primary surplus to changes in debt also shows that U. S. fiscal policy is satisfying an intertemporal budget constraint.

In other words, we make up for first-temporary-then-permanent spending boosts by a mix of growth and higher taxes. Krugman might well be happy with that scenario, but the data do show intertemporal interdependence for budgetary decisions, with a mix of persistence on one variable (spending) and mean-reversion on another (debt-gdp ratio). And if you think a lot of government spending is inefficient, you should still be troubled by apparently “temporary” spending bursts.

As with much of macroeconomics, I would apply a good dose of agnosticism to these results (noting that agnosticism is not the same as assuming zero effect), but still the correlations are consistent with my intuitions more generally.

Top marginal tax rates, 1958 vs. 2009

That is another excellent post from Timothy Taylor. Excerpt:

It’s interesting to note that the share of income tax revenue collected by those in the top brackets for 2009–that is, the 29-35% category, is larger than the rate collected by all marginal tax brackets above 29% back in the 1960s.

And:

Raising tax rates on those with the highest incomes would raise significant funds, but nowhere near enough to solve America’s fiscal woes. Baneman and Nunns offer this rough illustrative estimate: “If taxable income in the top bracket in 2007 had been taxed at an average rate of 49 percent, income tax liabilities (before credits) would have been $78 billion (6.7 percent of total pre-credit liabilities) higher, taking into account likely taxpayer behavioral responses to the rate increase.” The behavioral response they assume is that every 10% rise in tax rates causes taxable income to fall by 2.5%.

And this zinger:

One could also use the example of 1959 to argue that many more taxpayers in the broad range of lower- and middle-incomes should face marginal federal tax rates in the range of 16-28%.

I do not favor such a shift, yet somehow that is a neglected comparison.

Gallup fact of the day

All of postwar development economics in one exchange?

Check out the book Economic Development for Latin America, edited by Howard S. Ellis and Henry C. Wallich, circa 1961 and read Paul Rosenstein-Rodan’s classic essay “Notes on the Theory of the “Big Push””.

In ten pages you get the essence of increasing returns arguments, though do see Paul Krugman’s cautionary notes about this era and its lack of formal modeling.

After those ten pages, there is then Celso Furtado, that underrated and perhaps someday forgotten Brazilian economist, who in five pages tries to take PRR apart. The big push didn’t work in Bolivia, and in conclusion

“The point is not, therefore, to show that there are indivisibilities in the production function. The main interest lies in demonstrating how processes can be modified so as to elude the effects of those indivisibilities.”

The reader is then treated to three and a half pages of Ragnar Nurske, who shores up PRR.

There is then transcribed discussion, including remarks from Theodore Schulz (he rejects big push as an analytical tool), Albert Hirschman, Howard Ellis, Henry Wallich, more from Nurske, and Haberler, who wrote:

“…the lumpy factor could often be stretched to accommodate a varying amount of the co-operating factors. The big push was no substitute for normal piecemeal progress.”

That was a popular point in those days. Hirschman also…

“doubted that as a general rule overhead facilities would create a demand for their services. This depended on the kind of entrepreneurship available. Certainly there was no fixed short-run relation between investment in overhead and other investment, since overhead could be stretched.”

Nurske then fought back. Whew!

Reading those twenty pages exhausted me, and transported me to another and earlier era. It was like watching one of those taped 1980s NBA games, as they show them in Taiwan and some other countries, without the timeouts and breaks and besides they weren’t playing much defense anyway.

Overall it raised my estimation of those economists.

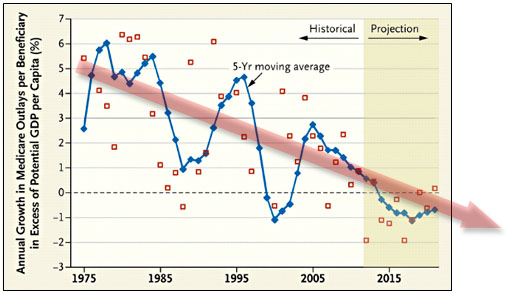

Is Medicare cost growth slowing down?

A lot is at stake here. Kevin Drum has a good summary of some recent work:

Via Sarah Kliff, a pair of researchers have taken a look at per-capita Medicare spending and concluded that it’s on a long-term downward path which is likely to continue into the future. Their claim is pretty simple: Although Medicare’s sustainable growth rate formula has been overridden year after year (this is the infamous annual “doc fix”), they say that other attempts to rein in spending have actually been pretty effective. This suggests that the cost controls in Obamacare have a pretty good chance of being effective too. Their basic chart is below, and since we’re all about the value-added around here I’ve added a colorful red arrow to indicate the trajectory.

(Note that their calculations are based on potential GDP, not actual GDP. I’m not sure why, but I assume it’s to control for the effects of recessions and boom years.)

Now, this calculation is per beneficiary, which means that overall Medicare costs will still go up if the number of beneficiaries goes up — which it will for the next few decades as the baby boomer generation ages. There’s really nothing to be done about that, though. Demographic bills just have to be paid. Nonetheless, if we can manage to keep benefits per beneficiary stable compared to GDP we’ll be in pretty good shape.

While I would say “too soon to tell” (for me only the post-2005 data points mean very much vis-a-vis the original question), I would not dismiss such reports out of hand.

American public opinion toward the space program

From Alexis Madrigal, this was news to me:

In thinking about the recent battles over NASA’s budget, it seems like the problem is simply citizen support. People don’t care that much about space, so space doesn’t get funded. Back in the Apollo days, people loved the space program! Except, as this Space Policy paper pointed out, they didn’t. A majority of Americans opposed the government funding human trips to the moon both before (July 1967) and after (April 1970) Neil Armstrong took a giant leap for mankind. It was only in the months surrounding Apollo 11 that support for funding the program ever reached above 50 percent.

*Turing’s Cathedral*

The author is George Dyson and the subtitle is The Origins of the Digital Universe. It is a first-rate, splendid book, causing us to rethink the origins of computing systems, the connections between early computers and nuclear weapons systems, how to motivate geniuses, and also the career of John von Neumann. Here is one excerpt, I may be giving you more:

In 1943, Bigelow left MIT, reassigned by Warren Weaver to the NDRC Applied Mathematics Panel’s Statistical Research Group. Under the auspices of Columbia University, eighteen mathematicians and statisticians — including Jacob Wolfowitz, Harold Hotelling, George Stigler, Abraham Wald, and the future economist Milton Friedman — tackled a wide range of wartime problems, starting with the question of “whether it would be better to have eight 50 caliber machine guns on a fighter plane or four 20 millimeter guns.”

Here is one Francis Spufford article about the book. Definitely recommended.