Category: Medicine

Sugar doesn’t cause hyperactivity

Here is Aaron Carroll at The Incidental Economist:

Let’s cut to the chase: sugar doesn’t make kids hyper. There have been at least twelve trials of various diets investigating different levels of sugar in children’s diets. That’s more studies than are often done on drugs. None of them detected any differences in behavior between children who had eaten sugar and those who hadn’t. These studies included sugar from candy, chocolate, and natural sources. Some of them were short-term, and some of them were long term. Some of them focused on children with ADHD. Some of them even included only children who were considered “sensitive” to sugar. In all of them, children did not behave differently after eating something full of sugar or something sugar-free….

In my favorite of these studies, children were divided into two groups. All of them were given a sugar-free beverage to drink. But half the parents were told that their child had just had a drink with sugar. Then, all of the parents were told to grade their children’s behavior. Not surprisingly, the parents of children who thought their children had drunk a ton of sugar rated their children as significantly more hyperactive. This myth is entirely in parents’ heads. We see it because we believe it.

Even when science shows time and again that it’s not so, we continue to persist in believing that sugar causes our kids to be hyperactive. That’s likely because there’s an association. Times when kids get a lot of sugar are often times when they are predisposed to be a little excited. Halloween. Birthday parties. Holidays. We may even be causing the problem ourselves. Some parents are so restrictive about sugar and candy that when their kids finally get it they’re quite excited. Even hyper.

This does not mean that there aren’t a ton of great reasons why our kid should not ingest large quantities of sugar. As almost any parent knows, sugar has been linked to cavities and the obesity epidemic. Just don’t blame it for your child’s bad behavior.

I would not have written the paragraph this way

This is from the NYT:

Even the generic drug industry is calling for more regulation. The industry recently agreed to provide the F.D.A. with nearly $300 million annually to bolster inspections and speed drug applications. That amounts to about 1 percent of the industry’s revenues and about 5 percent of its profits in the United States, an extraordinary vote of confidence in the government’s ability to improve the situation.

Markets in everything the culture that is Japan

Meanwhile, in Japan, a new fashion has women paying to have their straight teeth purposefully disarranged.

A result of tooth-crowding commonly derided in the United States as “snaggleteeth” or “fangs,” the look is called “yaeba” in Japanese or “double tooth.” Japanese men are said to find this attractive: blogs are devoted to yaeba, celebrities display it proudly, and now some women are paying dentists to create it artificially by affixing plastic fronts to their real teeth.

“It’s not like here, where perfect, straight, picket-fence teeth are considered beautiful,” said Michelle Phan, a Vietnamese-American based in Los Angeles, who wrote about the phenomenon on her popular beauty blog. “In Japan, in fact, crooked teeth are actually endearing, and it shows that a girl is not perfect. And, in a way, men find that more approachable than someone who is too overly perfect.”

Here is more, thanks to Jack Kessler for the pointer.

Report from the front line

Chancellor Angela Merkel said on Saturday that the European Central Bank has just one mission — to ensure monetary stability.

Merkel said in a speech to her Christian Democrats in Braunschweig on Saturday that treaties prevent the ECB from taking on any other tasks, such as those such as the U.S. Federal Reserve have.

That could be a clever Straussian feint and bluff, but with what probability? I don’t think so, I think it is for real.

A point of light

The Obama administration moved Tuesday to roll back a number of rules governing hospitals and other health care providers after concluding that the standards were obsolete or overly burdensome to the industry.

Among other things, the proposals would allow hospitals to save money by sometimes using qualified nurse practitioners and physician assistants in place of better-paid doctors, allowing doctors to focus more on patients and helping address “impending physician shortages.”

Here is more. Had I been President, this would have been one of my priorities from day one.

Bone Marrow Bounty Hunters

Amit Gupta has leukemia and needs to find a bone-marrow transplant. Gupta is the founder of the do-it-yourself photography site Photojojo and the collaborative-working community Jelly and many of his high-tech friends have jumped to his aid including Seth Godin. Here’s Virginia Postrel:

[Godin offered] to pay $10,000 to anyone who became a match for Gupta and made the stem-cell donation, or to give the money to that person’s favorite charity. The offer, he says, was “a chance to say to my readers, ‘Hey, I care about this. A lot. Money where my mouth is.’”

He picked $10,000 because, he says, it’s “enough money to matter to both the giver and the recipient, without being enough money to sue over, cheat over or corrupt.”

Gupta’s friend Michael Galpert, one of the co-founders of the photo-editing site Aviary.com, quickly matched Godin’s offer. “I would do anything that could contribute to helping save his life,” he says.

With $20,000 at stake, the cause did indeed take on new urgency….There was only one problem. The offer was illegal.

Paying a marrow donor is currently illegal under the same law that makes paying organ donors illegal, despite the fact that marrow donation (technically blood stem cells from marrow) is much more like blood donation or egg donation than donating a kidney. (To avoid the law Godin has modified his offer.) Fortunately, the law might be overturned.

In February, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals heard arguments in a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the ban on valuable consideration for bone-marrow donations. The suit was brought by the Institute for Justice, a libertarian public-interest law firm, on behalf of plaintiffs who include patients, parents of sick children, a doctor who does bone- marrow transplants and a charity that would like to offer incentives, such as scholarships, to encourage more donations.

The lawsuit argues that since marrow cell transplants aren’t significantly different from blood transfusions, the federal government has no “rational basis” for outlawing the kind of compensation that is perfectly legal not only for blood but also for other regenerating tissues, such as hair and sperm, not to mention eggs, which don’t regenerate. This disparate treatment of essentially similar processes, it maintains, violates the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection. A decision could come down any day.

Not a CLASS Act

When President Obama’s health care proposal was being debated we were repeatedly told that the “The president’s plan represents an important step toward long-term fiscal sustainability.” Indeed, a key turning point in the bill’s progress was when the CBO scored it as reducing the deficit by $130 billion over 10 years making the bill’s proponents positively giddy, as Peter Suderman put it at the time. Of course, many critics claimed that the cost savings were gimmicks but their objections were overruled.

One of the budget savings that the critics claimed was a gimmick was that a new long-term care insurance program, The Community Living Assistance Services and Supports program or CLASS for short, was counted as reducing the deficit. How can a spending program reduce the deficit? Well the enrollees had to pay in for at least five years before collecting benefits so over the first 10 years the program was estimated to reduce the deficit by some $70-80 billion. Indeed, these “savings” from the CLASS act were a big chunk of the 10-yr $130 billion in deficit reduction for the health care bill.

The critics of the plan, however, were quite wrong for it wasn’t a gimmick, it was a gimmick-squared, a phantom gimmick, a zombie gimmick:

They’re calling it the zombie in the budget.

It’s a long-term care plan the Obama administration has put on hold, fearing it could go bust if actually implemented. Yet while the program exists on paper, monthly premiums the government may never collect count as reducing federal deficits.

Real or not, that’s $80 billion over the next 10 years….

“It’s a gimmick that produces phantom savings,” said Robert Bixby, executive director of the Concord Coalition, a nonpartisan group that advocates deficit control..

“That money should have never been counted as deficit reduction because it was supposed to be set aside to pay for benefits,” Bixby added. “The fact that they’re not actually doing anything with the program sort of compounds the gimmick.”

Moreover, there were many people inside the administration who thought that the program could not possibly work and who said so at the time. Here is Rick Foster, Chief Actuary of HHS’ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on an earlier (2009) draft of the proposal:

The program is intended to be “actuarially sound,” but at first glance this goal may be impossible. Due to the limited scope of the insurance coverage, the voluntary CLASS plan would probably not attract many participants other than individuals who already meet the criteria to qualify as beneficiaries. While the 5-year “vesting period” would allow the fund to accumulate a modest level of assets, all such assets could be used just to meet benefit payments due in the first few months of the 6th year. (italics added)

So we have phantom savings from a zombie program and many people knew at the time that the program was a recipe for disaster.

Now some people may argue that I am biased, that I am just another free market economist who doesn’t want to see a new government program implemented no matter what, but let me be clear, this isn’t CLASS warfare, this is math.

Hat tip: Andrew S.

Personalized Medicine

Patient X was rushed to the hospital for emergency surgery. As she entered the hospital she said to the anesthesiologist, “You may not want to use suxamethonium on me.”

“Have you had a previous reaction?” inquired the anesthesiologist.

“No.”

“Ah, a family member must have had a reaction.”

“No.”

“Why then are you concerned about this drug?”

“I’ve had a good portion of my genome sequenced,” the patient replied, “and I found that I have a genetic variation in the enzyme that breaks down suxamethonium and am part of the 5% of patients who respond unusually to this drug. I thought you should be aware of this information.”

The flabbergasted anesthesiologist wondered how long it would be before more of her patients came prepared with their own genetic code.

I made up the details of the conversation above, but otherwise the story is true. The patient was a customer of 23andme, a service that for around $200 will give you information on about half a million sites on your genome, how you differ from other people at those sites, and which of your variations are associated with various diseases, behaviors and capabilities.

The costs of sequencing are falling so rapidly it will soon make sense for everyone to carry their entire genetic code with them on a USB drive (23andme only identifies part of the code). In 2001 it cost Craig Venter $100,000,000 to sequence the first human genome (his own.) Today, it costs just $16,000; in a few years, it will cost less than $1,000–a 100,000-factor decrease in costs in less than two decades!

That’s me from a piece called The FDA and Personalized Medicine written to help launch a new blog from the Manhattan Institute, Medical Progress Today. I go on to argue that if we are to take advantage of the new possibilities for personalization “we must move the FDA away from pre-market gatekeeping and towards post-market surveillance and information provision.”

David Henderson, Rita Numerof and Paul Howard all comment.

The You Have Two Cows Challenge

No doubt you are familiar with the two cows guide to political philosophy.

- Socialism: You have t

wo cows. The government takes one and gives it to your neighbor.

wo cows. The government takes one and gives it to your neighbor.

- Communism: You have two cows. You give them to the Government, and the Government then sells you some milk.

- Capitalism: You have two cows. You sell one and buy a bull.

So under what type of ism do you have two cows but the government says that you can’t drink their milk? Whatever we call such an ism it may help to know that it is the one we live under. In a recent case in Wisconsin, as summarized by the judge (earlier case here):

Plaintiffs argue that they have a fundamental right to possess, use and enjoy their property and therefore have a fundamental right to own a cow, or a heard [sic] of cows, and to use their(s) in a manner that does not cause harm to third parties. They argue that they have a fundamental right to privacy to consume the food of their choice for themselves and their families and therefore a fundamental right to consume unpasteurized milk from their cows.

In response, Judge Fiedler wrote:

No, Plaintiffs do not have a fundamental right to own and use a dairy cow or a dairy herd;

No, Plaintiffs do not have a fundamental right to consume the milk from their own cow;

No, Plaintiffs do not have a fundamental right to produce and consume the foods of their choice…

So MR readers, here is the challenge: You have two cows. The government says that you cannot drink their milk. What ___ism?

My suggestions?

Paternalism is the obvious choice but I am going to go with Animal Farmism.

Confronting the cost of health care

Megan McArdle writes:

There are entitities in the private sector like unions who do, in fact, directly confront the tradeoff between benefits and pay. Many unions run their own health plans; most of them negotiate a pay package in which the tradeoff between more pay or more benefits is extremely specific. What these entities seem to show is that even people who are very well aware of how much things cost, choose bundling and price insulation over transparency and efficiency. As far as I know, they rarely choose cost control in any way that significantly inhibits participant autonomy, or increases price exposure.

There is more here.

Andy Grove on Reforming the FDA

In an important editorial in Science, Andy Grove, former Chief Executive Officer of Intel Corporation, advocates restricting the FDA to safety-only trials. Instead of FDA required efficacy trials patients would be tracked using a very large, open database.

The biomedical industry spends over $50 billion per year on research and development and produces some 20 new drugs….A breakthrough in regulation is needed to create a system that does more with fewer patients.

While safety-focused Phase I trials would continue under their [FDA] jurisdiction, establishing efficacy would no longer be under their purview. Once safety is proven, patients could access the medicine in question through qualified physicians. Patients’ responses to a drug would be stored in a database, along with their medical histories. Patient identity would be protected by biometric identifiers, and the database would be open to qualified medical researchers as a “commons.” The response of any patient or group of patients to a drug or treatment would be tracked and compared to those of others in the database who were treated in a different manner or not at all. These comparisons would provide insights into the factors that determine real-life efficacy: how individuals or subgroups respond to the drug. This would liberate drugs from the tyranny of the averages that characterize trial information today. The technology would facilitate such comparisons at incredible speeds and could quickly highlight negative results. As the patient population in the database grows and time passes, analysis of the data would also provide the information needed to conduct postmarketing studies and comparative effectiveness research.

Grove cites Boldin and Swamidass and especially Bartley Madden’s important book, Free to Choose Medicine, as inspiration for this proposal. By the way, I also recommend Madden’s book very highly (I am also proud to note my bias in this regard).

I have long advocated restricting the FDA to safety only trials (see, for example, FDAReview.org and my paper on off-label prescribing) and it seems that this idea, once considered outlandish, is now rapidly gathering advocates.

Addendum: Derek Lowe offers useful comments (see also Kevin Outterson below). One point that I think the critics miss is that nothing in Groves’s proposal and certainly not in Madden’s proposal which is somewhat different or in anything that I have advocated precludes randomized clinical trials for efficacy. Indeed, I strongly support such trials and have argued for greater funding so such trials can be done not by the pharmaceutical companies but by more objective third parties.

Contagion

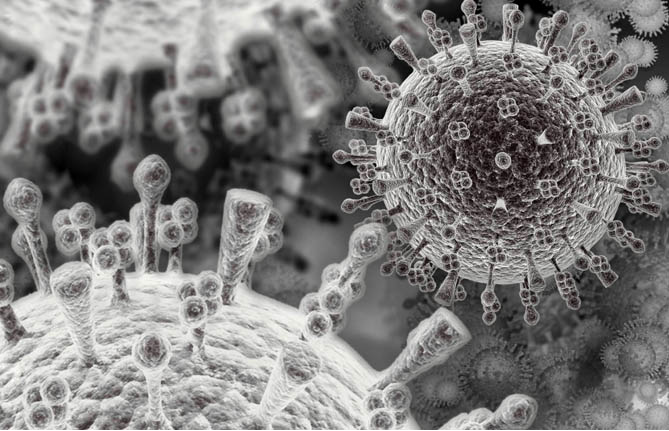

Contagion, the Steven Soderberg film about a lethal virus that goes pandemic, succeeds well as a movie and very well as a warning. The movie is particularly good at explaining the science of contagion: how a virus can spread from hand to cup to lip, from Kowloon to Minneapolis to Calcutta, within a matter of days.

One of the few silver linings from the 9/11 and anthrax attacks is that we have invested some $50 billion in preparing for bio-terrorism. The headline project, Project Bioshield, was supposed to produce vaccines and treatments for anthrax, botulinum toxin, Ebola, and plague but that has not gone well. An unintended consequence of greater fear of bio-terrorism, however, has been a significant improvement in our ability to deal with natural attacks. In Contagion a U.S. general asks Dr. Ellis Cheever (Laurence Fishburne) of the CDC whether they could be looking at a weaponized agent. Cheever responds:

Someone doesn’t has to weaponize the bird flu. The birds are doing that.

That is exactly right. Fortunately, under the umbrella of bio-terrorism, we have invested in the public health system by building more bio-safety level 3 and 4 laboratories including the latest BSL3 at George Mason University, we have expanded the CDC and built up epidemic centers at the WHO and elsewhere and we have improved some local public health centers. Most importantly, a network of experts at the department of defense, the CDC, universities and private firms has been created. All of this has increased the speed at which we can respond to a natural or unnatural pandemic.

In 2009, as H1N1 was spreading rapidly, the Pentagon’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency asked Professor Ian Lipkin, the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, to sequence the virus. Working non-stop and updating other geneticists hourly, Lipkin and his team were able to sequence the virus in 31 hours. (Professor Ian Sussman, played in the movie by Elliott Gould, is based on Lipkin.) As the movie explains, however, sequencing a virus is only the first step to developing a drug or vaccine and the latter steps are more difficult and more filled with paperwork and delay. In the case of H1N1 it took months to even get going on animal studies, in part because of the massive amount of paperwork that is required to work on animals. (Contagion also hints at the problems of bureaucracy which are notably solved in the movie by bravely ignoring the law.)

It’s common to hear today that the dangers of avian flu were exaggerated. I think that is a mistake. Keep in mind that H1N1 infected 15 to 30 percent of the U.S. population (including one of my sons). Fortunately, the death rate for H1N1 was much lower than feared. In contrast, H5N1 has killed more than half the people who have contracted it. Fortunately, the transmission rate for H5N1 was much lower than feared. In other words, we have been lucky not virtuous.

We are not wired to rationally prepare for small probability events, even when such events can be devastating on a world-wide scale. Contagion reminds us, visually and emotionally, that the most dangerous bird may be the black swan.

Good news, sort of

Medicare’s growth slowdown has been much greater than that of private health insurance, however, as Maggie Mahar has noted on the Century Foundation’s Health Beat blog. In the 12-month period that ended in June 2011, Standard & Poor’s index for commercial health insurance rose 7.5 percent, while its Medicare index rose only 2.5 percent. The S&P data show that Medicare spending growth has been falling fairly steadily over the past 18 months.

That is from Peter Orszag, interesting throughout. Some of this may actually be productivity improvements.

Possible progress in medicine

…in a development that could transform how viral infections are treated, a team of researchers at MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory has designed a drug that can identify cells that have been infected by any type of virus, then kill those cells to terminate the infection.

…In a paper published July 27 in the journal PLoS One, the researchers tested their drug against 15 viruses, and found it was effective against all of them — including rhinoviruses that cause the common cold, H1N1 influenza, a stomach virus, a polio virus, dengue fever and several other types of hemorrhagic fever.

The drug works by targeting a type of RNA produced only in cells that have been infected by viruses. “In theory, it should work against all viruses,” says Todd Rider…

The press release is here and for the pointer I thank Martin Laurence. Let’s see how long it takes to come on-line…

FDA: Moving to a Safety-Only System

It now costs about a billion dollars to develop a new drug which means that many potentially beneficial drugs are lost. Economist Michele Boldrin and physician S. Joushua Swamidass explain the problem and suggest a new approach:

Every drug approval requires a massive bet—so massive that only very large companies can afford it. Too many drugs become profitable only when the expected payoff is in the billions….in this high-stakes environment it is difficult to justify developing drugs for rare diseases. They simply do not make enough money to pay for their development….How many potentially good drugs are dropped in silence every year?

Finding treatments for rare disease should concern us all. And as we look closely at genetic signatures of important diseases, we find that each common disease is composed of several rare diseases that only appear the same on the outside.

Nowhere is this truer than with cancer. Every patient’s tumor is genetically unique. That means most cancer patients have in effect a rare disease that may benefit from a drug that works for only a small number of other patients.

…We can reduce the cost of the drug companies’ bet by returning the FDA to its earlier mission of ensuring safety and leaving proof of efficacy for post-approval studies and surveillance.

Harvard Neurologist Peter Lansbury made a similar argument several years ago:

There are also scientific reasons to replace Phase 3. The reasoning behind the Phase 3 requirement — that the average efficacy of a drug is relevant to an individual patient — flies in the face of what we now know about drug responsiveness. Very few drugs are effective in all individuals. In fact, most are not effective in large portions of the population, for reasons that we are just beginning to understand.

It’s much easier to get approval for drugs that are marginally effective in, say, half the population than drugs that are very effective in a small fraction of patients. This statistical barrier discourages the pharmaceutical industry from even beginning to attack diseases, such as Parkinson’s, that are likely to have several subtypes, each of which may respond to a different drug. These drugs are the underappreciated casualties of the Phase 3 requirement; they will never be developed because the risk of failure at Phase 3 is simply too great.

Boldrin and Swamidass offer another suggestion:

In exchange for this simplification, companies would sell medications at a regulated price equal to total economic cost until proven effective, after which the FDA would allow the medications to be sold at market prices. In this way, companies would face strong incentives to conduct or fund appropriate efficacy studies. A “progressive” approval system like this would give cures for rare diseases a fighting chance and substantially reduce the risks and cost of developing safe new drugs.

Instead of price regulations I have argued for more publicly paid for efficacy studies, to be produced by the NIH and other similar institutions. Third party efficacy studies would have the added benefit of being less subject to bias.

Importantly, we already have good information on what a safety-only system would look like: the off-label market. Drugs prescribed off-label have been through FDA required safety trials but not through FDA-approved efficacy trials for the prescribed use. The off-label market has its problems but it is vital to modern medicine because the cutting edge of treatment advances at a far faster rate than does the FDA (hence, a majority of cancer and AIDS prescriptions are often off-label, see my original study and this summary with Dan Klein). In the off-label market, firms are not allowed to advertise the off-label use which also gives them an incentive, above and beyond the sales and reputation incentives, to conduct further efficacy studies. A similar approach might be adopted in a safety-only system.

Addendum: Kevin Outterson at The Incidental Economist and Bill Gardner at Something Not Unlike Research offer useful comments.