Category: Uncategorized

The Effect of Communism on People’s Attitudes Toward Immigration

Does living in a communist regime make a person more concerned about immigration? This paper argues conceptually and demonstrates empirically that people’s attitudes toward immigration are affected by their country’s politico-economic legacy. Exploiting a quasi-natural experiment arising from the historic division of Germany into East and West, I show that former East Germans, because of their exposure to communism, are notably more likely to be very concerned about immigration than former West Germans. Opposite of what existing literature finds, higher educational attainment in East Germany actually increases concerns. Further, I find that the effect of living in East Germany is driven by former East Germans who were born during, and not before, the communist rule and that differences in attitudes persist even after Germany’s reunification. People’s trust in strangers and contact with foreigners represent two salient channels through which communism affects people’s preferences toward immigration.

That is from Matthew Karl at the Board of Governors, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

*The Revolt of The Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium*

By Martin Gurri, due out November 13. I am reading this splendid book for the first time. It basically explains why Brexit and Trump won, and what will happen next. Due to social media, we are disillusioned with our elites, and that will prove hard to reverse.

Friday assorted links

1. Michael Young and meritocracy.

2. David Perell podcast with Daniel Gross.

3. Who dislikes “political correctness”?

4. American Economic Review: Insights, first set of papers now on-line.

The Civil War boosted Northern support for immigration

Here we arrive at one of the least appreciated factors in the equation that led to the Union victory: the military service of immigrants. Foreign-born recruits provided the Union army with the advantage it needed over its Confederate rival. An estimated 25 percent of the soldiers in the Union army (some 543,000) and more than 40 percent of the seamen in the navy (84,000) were foreign-born. If one includes soldiers with at least one immigrant parent, the overall figure climbs to 43 percent of the Union army…

The demands of war meant that Union officials needed to appeal to immigrants. Military recruitment placards were printed in foreign languages; Union officials presented the war as part of a transnational struggle for republican government, thereby decoupling the idea of the nation from Anglo-Saxon Protestantism…

The military service of the foreign-born did more than enhance the Union’s advantage in the field. It also transformed the politics of nativism in the United States. From the nativism of the 1850s, exemplified by Know-Nothingism and bigoted anti-Catholicism, the Union now moved in the direction of welcoming — indeed, encouraging — foreign arrivals.

That is all from the new book by Jay Sexton, A Nation Forged by Crisis: A New American History.

Why is the news cycle getting shorter and shorter?

Remember the anonymous Op-Ed from within the Trump administration? We’re hardly talking about it any more, and indeed so many “major” stories from just a few weeks ago seem to be slipping from our grasp. Why?

The naïve hypothesis is that we keep turning our attention to the very latest events because so much is happening so quickly. But there have been periods in the past when a lot was happening, such as the financial crisis of a decade ago, and the news cycle seemed “stickier” then. So this can’t be the entire story.

An alternate theory is that there are actually very few “true events” happening, but there is lots of froth on the surface. Maybe there is only one “big event” happening, one major transformation underway: a change in the willingness of American political leaders to break with previous norms. If the change is mostly in one direction, then maybe it’s enough to debate only the most recent news.

That may sound abstract, so here is a concrete analogy. Let’s say you are on a sinking ship. You might focus more on the current water level than on where it was in the recent past, except maybe to help you estimate the rate of flooding. In more technical terms, talking about the event of the day is a “sufficient statistic” for talking about the last two years.

The shorter news cycle also may result from greater political polarization. If people don’t frame events in a common way, then a discussion of those events might not last very long. Conversation will return very quickly to the underlying differences in worldviews, and discussion of any particular event will get trampled by a much larger philosophical debate. It does seem like we have been repeating the same general arguments about Trump, populism, gender and governing philosophy for some time now, and we are not about to stop.

Possibly the shorter news cycles are also a result of greater general disillusionment with politics and especially with elites, a theme outlined in Martin Gurri’s forthcoming book “The Revolt of the Public.” The really fun stuff might instead be watching mixed martial arts, debating social norms about gender and browsing the Instagram feeds of your friends.

Finally, maybe we’re all just better at digesting news events more quickly. Perhaps every possible observation, insight and argument gets put on Facebook and Twitter within a day or two, and much of this material is archived. What’s the point of repeating these debates every few months?

That is from my latest Bloomberg piece. I am thankful to Anecdotal for a related point and insight.

Thursday assorted links

1. Why Eastern Europe is not about to turn pro-immigration.

2. Next week: Ben Sasse has a new book out: Them: Why We Hate Each Other — And How to Heal.

3. Five facts about the new NAFTA.

4. Larger cities are also more unequal.

5. Do the most important artists make the most expensive paintings?

6. “The museum of accidents offers a glimpse into Japanese introspection.”

The funnel of human experience

So humanity in aggregate has spent about ten times as long worshiping the Greek gods as we’ve spent watching Netflix.

We’ve spent another ten times as long having sex as we’ve spent worshiping the Greek gods.

And we’ve spent ten times as long drinking coffee as we’ve spent having sex.

Furthermore:

It turns out that if you add up all these years, 50% of human experience has happened after 1309 AD. 15% of all experience has been experienced by people who are alive right now.

This should cheer you all up, yes indeed there is no great stagnation no wonder the rate of productivity growth has been so high:

FHI reports that 90% of PhDs that have ever lived are alive right now.

That is from eukaryote at LessWrong. Hat tip goes to the always-excellent The Browser.

Wednesday assorted links

My Conversation with Paul Krugman

Here is the audio and transcript, here is part of the summary:

Tyler sat down with Krugman at his office in New York to discuss what’s grabbing him at the moment, including antitrust, Supreme Court term limits, the best ways to fight inequality, why he’s a YIMBY, inflation targets, congestion taxes, trade (both global and interstellar), his favorite living science fiction writer, immigration policy, how to write well for a smart audience, new directions for economic research, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: In your view, how well run is New York City as an entity?

KRUGMAN: Not very. Compared to what? Actually, I like de Blasio. I actually think he’s done some really good things. What he’s done on education, and even on affordable housing, is actually quite substantial. But the city is so big and the problems are so large that people may not get it.

I will say, it is crazy that you have a city that is so dependent on public transportation, and yet the public transportation is not actually under the city’s control and has clearly been massively neglected. I don’t suffer the full woes of the subway, but I suffer some of them, even myself.

The city could be run better than it is, but it’s certainly not among the worst-managed political entities in the United States, let alone in the world.

And:

COWEN: Will there ever be interstellar trade in intellectual property? You send your technology to a planet far away. It arrives much later, of course. Or you trade Beethoven to the aliens in return for a transporter beam? Can this work? You’ve written a paper that seems to indicate it can work.

KRUGMAN: I wrote a paper on the theory of interstellar trade when I was an unhappy assistant professor. Are there any happy assistant professors? [laughs] I was just blowing off steam. But it’s an interesting question.

COWEN: It could become your most important paper, right? [laughs]

KRUGMAN: We could imagine that there would be some way. We’d have to find somebody to trade with, although it’s the kind of thing — if you try to imagine interstellar trade for real in intellectual property — it’s probably the kind of thing that would be more like government-to-government exchanges.

It sounds like it would be really, really hard, although some science fiction writers are imagining that something like Bitcoin would make it possible to do these long-range . . . I don’t think something like Bitcoin is even going to work here.

Krugman also gives his opinions on Star Wars and Star Trek and Big Tech and many other matters. Interesting throughout…

Indian airport police are going to smile less

Airport police in India are being instructed to smile less.

This is over concerns cheerfulness could lead to a perception of lax security and a threat of terror attacks.

The country’s Central Industrial Security Force, which is in charge of aviation safety, wants its staff to be “more vigilant than friendly”.

They will move from a “broad smile system” to a “sufficient smile system”, the Indian Express says.

Officials are said to believe that excessive friendliness puts airports at risk of terrorist attacks.

The organisation’s director general, Rajesh Ranjan even said the 9/11 attacks had taken place because of “an excessive reliance on passenger-friendly features”.

Here is the full story, via Anecdotal.

Assorted Tuesday links

1. Old Paul Romer talk, which even presents the Nordhaus graph on the price of light, see for instance 5:45. Via Kari Kohn.

2. New criticism of charter cities, and Mark Lutter’s response.

3. Lambda School.

4. Larry Summers road trip. Or try this link.

5. How Ray Fair is modeling running, and aging (NYT).

6. Why is the William Nordhaus optimal carbon tax so modest? And A Fine Theorem on Romer and Nordhaus.

Preference for realistic art predicts support for Brexit

Here is part of the abstract from Noah Carl, Lindsay Richards, and Anthony Heath:

Controlling for a range of personal characteristics, we found that respondents who preferred all four realistic paintings were 15–20 percentage points more likely to support Leave than those who preferred zero or one realistic paintings. This effect was comparable to the difference in support between those with a degree and those with no education, and was robust to controlling for the respondent’s party identity.

Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Assorted Monday links

William Nordhaus and why he won the Nobel Prize in economics

These are excellent Nobel Prize selections, Romer for economic growth and Nordhaus for environmental economics. The two picks are brought together by the emphasis on wealth, the true nature of wealth, and how nations and societies fare at the macro level. These are two highly relevant picks. Think of Romer as having outlined the logic behind how ideas leverage productivity into ongoing spurts of growth, as for instance we have seen in Silicon Valley. Think of Nordhaus as explaining how economic growth interacts with the value of the environment. Here is their language:

- 2018 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences is awarded jointly to William D Nordhaus “for integrating climate change into long-run macroeconomic analysis” and Paul M Romer “for integrating technological innovations into long-run macroeconomic analysis”.

Both are Americans, and both have highly innovative but also “within the mainstream” approaches. So this is a macro prize, but not for cycles, rather for growth and long-term economic prospects. Here is the Prize committee citation, always well done.

Both candidates were considered heavy favorites to win the Prize, sooner or later, and these selections cannot come as a surprise. Perhaps it is slightly surprising that they won the Prize together, though the basic logic of such a combination makes good sense. Here are previous MR mentions of Nordhaus, you can see we have been mentioning him for years in connection with the Prize.

Here is the home page of Nordhaus. Here is Wikipedia. Here is scholar.google.com. Here is Joshua Gans on Nordhaus.

Nordhaus is professor at Yale, and most of all he is known for his work on climate change models, and his connection to various concepts of “green accounting.” To the best of my knowledge, Nordhaus started working on green accounting in 1972, when he published with James Tobin (also a Laureate) “Is Growth Obsolete?“, which raised the key question of sustainability. Green accounting attempts to outline how environmental degradation can be measured against economic growth. This endeavor is not so easy, however, as environmental damage can be hard to measure and furthermore gdp is a “flow” and the environment is (often, not always) best thought of as a “stock.”

Nordhaus developed (with co-authors) the Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy Model, a pioneering effort to develop a general approach to estimating the costs of climate change. Subsequent efforts, such as the London IPCC group, have built directly on Nordhaus’s work in this area. The EPA still uses a variant of this model. The model was based on earlier work by Nordhaus himself in the 1970s, and he refined it over time in a series of books and articles, culminating in several books in the 1990s. Here is his well-cited piece, with Mendelsohn and Shaw, on how climate change will affect global agriculture.

Nordhaus also was an early advocate of a carbon tax and furthermore note that his brother Bob wrote part of the Clean Air Act, the part that gave the government the right to regulate hitherto-unmentioned pollutants in the future. The Obama administration, in its later attempts to regulate climate, cited this provision.

I would say that much of Nordhaus’s work has its impact through being “done,” rather than through being “read.” Few economists have read through this model, which has computer programs and spreadsheets at its core. But virtually all economists read about the results of such models and have a general sense of how they work. The most common criticism of such models, by the way, is simply that their results are highly sensitive to the choice of discount rate.

In recent years, Nordhaus has shifted his emphasis to the risks from climate change, for instance in his book The Climate Casino: Risk, Uncertainty, and Economics for a Growing World. Marty Weitzman offers a good review, as does Krugman.

Assorted pieces of information on Nordhaus:

Nordhaus was briefly Provost at Yale. He also ended up being co-author on Paul Samuelson’s famous textbook in economics.

He co-authored a recent paper arguing we are not near the economic singularity; in this area his work intersects with Romer’s quite closely.

Here is a good NYT profile of Bill Nordhaus and his brother Bob, an environmental lawyer:

Bill Nordhaus, 72, a Yale economist who is seen as a leading contender for a Nobel Prize, came up with the idea of a carbon tax and effectively invented the economics of climate change. Bob, 77, a prominent Washington energy lawyer, wrote an obscure provision in the Clean Air Act of 1970 that is now the legal basis for a landmark climate change regulation, to be unveiled by the White House next month, that could close hundreds of coal-fired power plants and define President Obama’s environmental legacy.

Bob, Bill’s brother, once said: ““Growing up in New Mexico,” he said, “you’re aware of the very fragile ecosystem.””

Perhaps my personal favorite Nordhaus paper is on the returns to innovation. Don Boudreaux summarized it well:

In a recent NBER working paper – “Schumpeterian Profits in the American Economy: Theory and Measurement” – Yale economist William Nordhaus estimates that innovators capture a mere 2.2% of the total “surplus” from innovation. (The total surplus of innovation is, roughly speaking, the total value to society of innovation above the cost of producing innovations.) Nordhaus’s data are from the post-WWII period.

The smallness of this figure is astounding. If it is anywhere close to being an accurate estimate, the implication is that “society” pays a paltry $2.20 for every $100 worth of welfare it enjoys from innovating activities.

There again you will see a complete intersection with the ideas of Romer. Another splendid and still-underrated paper by Nordhaus is on the economics of light. Nordhaus argues that gdp figures understate the true extent of growth, and shows that the relative price of bringing light to humans has fallen more rapidly than gdp growth figures alone might indicate. Check out this diagram. Here is a BBC summary of what Nordhaus did, in other words rates of price inflation have been lower than we thought and thus rates of real gdp growth higher.

Again, you will see Nordhaus and Romer intersecting on this key idea of economic growth.

Last but not least, Nordhaus was a pioneer on the theory of the political business cycle, namely the idea that politicians deliberately manipulate the economy, using monetary and fiscal policy, so as to boost their chances of reelection. Dare I suggest that this idea might be making a comeback?

Addendum: From Margaret Collins by email: “I’d like to call your attention to Professor Nordhaus’ longstanding association with the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), the international science and policy research institution located just outside Vienna. He worked at IIASA shortly after the institute’s creation in 1972, and his work there is closely bound to the issues the Nobel Committee cites in the award — he was employed for a year in 1974-75, doing pioneering work on climate as part of IIASA’s Energy Program, and producing a working paper entitled “Can We Control Carbon Dioxide?”. That was perhaps the first economics treatment of of climate change — and Nordhaus dates his work on climate as having begun there. He has visited IIASA numerous times in the intervening years, and remains a close collaborator, particularly with Nebojsa Nakicenovic, the Institute’s Deputy Director.”

And, from the comments: “Nordhaus also helped pioneer the use of satellite imagery of night time lights as a tool for measuring economic growth, where we’ve played around with some of the publicly available tools to support various analysis.”

Is the speed of skyscraper construction declining?

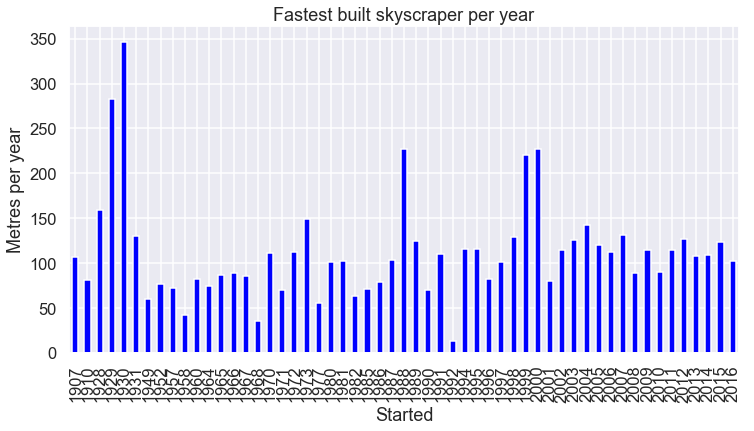

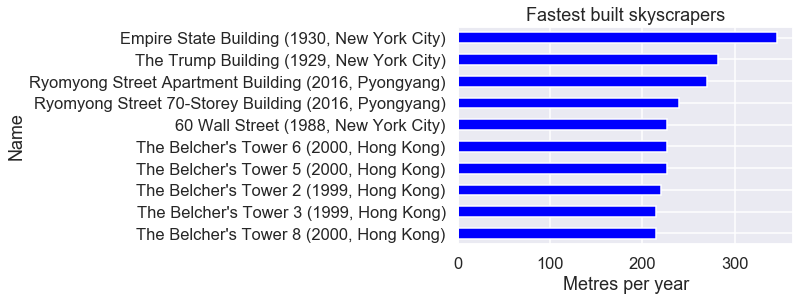

…taking not averages but just the fastest building built every year (again taking out Pyongyang and Broad Group), regardless of country. This seems to indicate that with the exception of The Belcher’s tower(s) in HK and 60 Wall St, in general construction speed has remained stagnant for almost a century, and has actually declined since its peak in the Great Depression.

The early 1930s look pretty amazing. The data on meters built per year, and the fastest built buildings by that standard are interesting too:

There is much, much more in this post, which I consider to be one of the best things written this year. Here is Artir’s conclusion:

…the Empire State Building was an impressive achievement compared to the present, but it’s not true that the past has been better than the present; rather, the skyscrapers built during the Great Depression were.

Highly recommended, via Patrick Collison. And here is Artir on Twitter.