Category: Uncategorized

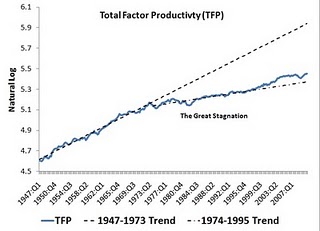

Total Factor Productivity

Assorted links

1. One measure of the value of computers.

2. Karl Smith on Garett Jones and TARP.

3. Photograph taken from Borders, a theory of optimal bundling, and yet the restroom in my house works just fine. They even let me take books into it for reading.

4. “Everything is obvious once you know the answer,” a new Duncan Watts book.

Assorted links

1. National serviceman needs maid to carry his backpack (Singapore, Adam Smith, decline of martial virtue, via Chris F. Masse).

2. Paul Krugman on the 1921 recovery.

3. Robin Hanson and Brian Christian.

4. Unemployment duration still going up.

5. Brad DeLong, slouching toward recalculation. And his response.

China price request of the day

Unilever, the Anglo-Dutch consumer goods group, has bowed to pressure from Beijing to delay planned price increases, highlighting a new regulatory risk in an inflationary climate.

…Chinese consumers, increasingly alarmed at the rising cost of living, cleared supermarket shelves this week of shampoos, soaps and detergents after state media said four consumer goods companies – including Unilever and Guangzhou Liby Enterprise Group – would raise prices by between 5 per cent and 15 per cent.

The full story is here.

Seminal books for each decade

Andrew asks a tough question:

what do you think is more or less the equivalent of the great gatsby in every decade after the 20s?

Here are my picks:

1930s: The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck.

1940s: Farewell, My Lovely, by Raymond Chandler.

1950s: Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison, with Kerouac’s On the Road as a runner-up.

1960s: Catch-22, by Joseph Heller, with The Bell Jar and Herzog as runners-up.

1970s: This is tough. There is Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions, Stephen King, and even Peter Benchley’s Jaws. I’ll opt for Benchley as a dark horse pick, note that these aren’t my favorites but rather they must be culturally central. Jonathan Livingston Seagull is another option, as this truly is an era of popular literature.

1980s: Tom Wolfe, The Bonfire of the Vanities.

1990s: The Firm, by John Grisham, or Barbara Kingsolver, The Poisonwood Bible. Maybe Brokeback Mountain.

2000s: Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point.

The Hayek Twitter game

The game: Take a sentence or two on Hayek’s clause and qualification ridden Germanic prose, and turn it into a 144 character twitter feed.

Example. Here’s a brief passage from Hayek 1976 essay “Socialism and Science” posted a few days ago in the comments by Richard Ebeling:

“A society in which everyone is organized as a member of some group to force government to help him get what he wants is self-destructive. There is no way from preventing some from feeling that they have been treated unjustly — that feeling is bound to be wide spread in any social order — but arrangements which enable groups of disgruntled people to extort satisfaction of their claims — or in the recognition of an ‘entitlement’, to use the new-fangled phrase — make any society unmanageable.”

And here it is as a 144 character twitter feed:

When everyone is organized to force government to get them what they want, many will be left feeling that they have been treated unjustly.

Ho hum! I would have done “Rent-seeking groups lead to perceptions of unfairness.”

When did the big gains in agricultural productivity come?

I had the general and indeed correct impression that U.S. agricultural productivity has been rising for a long time. It’s less commonly known how big was the productivity acceleration in agriculture in the 1940s. Between 1880 and 1940, agricultural productivity in this country rose at the rather modest rate of about one percent a year. After World War II, the trend rate of growth jumps to 2.8 percent annually. Multi-factor productivity in agriculture skyrockets in the mid-1930s, not earlier.

The information is from Bruce Gardner’s American Agriculture in the Twentieth Century: How it Flourished and What it Cost, pp.20-21, p.44.

My favorite things South Africa

Torr writes to me:

Please will you consider doing a “favorite things South Africa” on Marginal Revolution. I’m also curious: have you ever visited South Africa?

I have yet to go, but here is what I admire so far:

1. Visual artist (you can’t quite call him a painter): William Kentridge. He is one of the contemporary artists who is both a realist and has a lot of the emotional power of the classics. His extraordinary body of work spans film, drawings, prints, and mixed media. Here are some images.

2. Home design: I am an admirer of the Ndebele, some photos of their colorful homes are here. They are better represented in picture books than on the web.

3. Movies: I don’t know many. I enjoyed The Gods Must be Crazy, even though some might find it slightly offensive. Nonetheless I hand the prize to District 9 for its interesting take on ethnic politics, its deconstruction and mock of Afrikaaner settler myths, and its commentary on how South Africans view Zimbabwean immigrants to their country.

4. Movie, set in: Zulu, 1964 with Michael Caine.

5. Novels: My favorite Coetzee is Disgrace, though I like most of them very much, including the early Life and Times of Michael K and Waiting for the Barbarians and the later semi-autobiographical works. Nadine Gordimer I find unreadable, call the fault mine. Same with Alan Paton. A dark horse pick is Trionf. Agaat sits in my pile, waiting for the trip of the right length.

6. Music: Where to start? Malanthini, for one. As for mbqanga collections, The Indestructible Beat of Soweto series is consistently excellent. Singing in an Open Space, Zulu Rhythm and Harmony 1962-1982 is a favorite. Random gospel and jazz collections often repay the purchase price and in general random CD purchases in these areas bring high expected returns.

7. Economists: Ludwig Lachmann was an early teacher of mine and I owe him my interest in post Keynesianism and also financial fragility hypotheses. G.F Thirlby remains underrated. W.H. Hutt was one of the most perceptive critics of Keynes and his insights still are not absorbed into the Keynesian mainstream. His book on the economics of the colour bar remains a liberal classic. Who am I forgetting?

The bottom line: There’s a lot here. Here are previous MR posts about South Africa.

Assorted links

Assorted links

1. Facebook and TGS, and Robin Hanson reviews TGS. Mike Mandel responds to Karl Smith.

2. Is envy a stronger motivator than admiration?

3. Passing to yourself off the backboard (video).

4. Yet another way of viewing our labor market troubles, or in other words, start-ups have suffered too (NYT blog).

5. Via Chris F. Masse, when will China overtake the U.S. in science? (NB: I’m not convinced by this article).

The fallacy of mood affiliation

Recently I wrote:

It seems to me that people are first choosing a mood or attitude, and then finding the disparate views which match to that mood and, to themselves, justifying those views by the mood. I call this the “fallacy of mood affiliation,” and it is one of the most underreported fallacies in human reasoning. (In the context of economic growth debates, the underlying mood is often “optimism” or “pessimism” per se and then a bunch of ought-to-be-independent views fall out from the chosen mood.)

Here are some further examples:

1. People who strongly desire to refute those who predicted the world would run out of innovations in 1899 and thus who associate proponents of a growth slowdown with that far more extreme view. There’s simply an urgent feeling that any “pessimistic” view needs to be countered.

2. People who see a lot of net environmental progress (air and water are cleaner, for instance) and thus dismiss or downgrade well-grounded accounts of particular environmental problems. There’s simply an urgent feeling that any “pessimistic” view needs to be countered.

3. People who see a political war against the interests of the poor and thus who are reluctant to present or digest analyses which blame some of the problems of the poor on…the poor themselves. (Try bringing up “predatory borrowing” in any discussion of “predatory lending” and see what happens.) There’s simply an urgent feeling that any negative or pessimistic or undeserving view of the poor needs to be countered.

4. People who see raising or lowering the relative status of Republicans (or some other group) as the main purpose of analysis, and thus who judge the dispassionate analysis of others, or for that matter the partisan analysis of others, by this standard. There’s simply an urgent feeling that any positive or optimistic or deserving view of the Republicans needs to be countered.

In the blogosphere, the fallacy of mood affiliation is common.

Assorted links

2. Why you should ride escalators.

3. There is no Great Stagnation (video).

Assorted links

1. Secrets of success in Singapore.

2. The Art of Theory, a new on-line political philosophy quarterly; first issue has a symposium on Adam Smith.

3. Review of the new Peter Chang outlet in Chartlottesville.

4. Scott Winship’s statistical adjustment to male median wage estimates.

5. Actor Farley Granger dies at 85 (NYT).

Assorted links

1. How to avoid a gendered conference; at first I thought this was a Straussian satire by a confirmed chauvinist.

2. Yakuza step forward with relief supplies.

3. Zero marginal product Frank Lloyd Wright homes?

4. Persistent wage disparities in Britain are due to people rather than place.

How much productivity growth was there during 2007-2009?

Michael Mandel has a long and excellent blog post on this question. He claims that the supposed productivity gains were concentrated in a small number of sectors (one of which, by the way, was financial services ha-ha) and that they are mostly illusory when cross-checked with other sources of data. Here is his final conclusion:

However, the effect of the adjustment on the 2007-2009 period is spectacular. Productivity growth, which had been 1.6% annually in the original data, basically disappears. The decline in real GDP is twice as large (-1.3% per year in the original data, -2.9% in the adjusted data). And economists are no longer presented with the confounding puzzle of why unemployment rose so much with such a modest decrease in GDP–it’s because the decrease in GDP was not so modest. (see a piece here on Okun’s Law, which links GDP changes with unemployment changes).

His redone figures, by the way, are based on the assumption that intermediate inputs are growing and shrinking roughly at the rate of final product (Mandel believes we are mismeasuring these intermediate inputs and thus finding illusory productivity gains over that period.) Think of his alternative numbers as illustrative rather than necessarily his best estimate. The implications of his analysis include:

1. Productivity statistics aren’t well set up to cover outsourcing.

2. Beware of measured productivity gains, reaped over short periods of time, based on supposed drastic declines in intermediate inputs. We’re probably mismeasuring those inputs. Mike’s examples on these points are pretty convincing, walk through what he does for instance take a look at his numbers on mining: “Mining, for example, combines a 10% drop in real gross output with an apparent 46% drop in real intermediate inputs, leading to a reported 23% gain in real value-added and a 26% gain in productivity. It’s very hard to understand how intermediate inputs decline four times as fast as output!”

3. During the crisis, output fell more than we thought and thus our recovery isn’t going as well as we think. (By the way, this is the most effective critique of the ZMP hypothesis, since the implied decline in true output now comes much closer to matching the measured decline of employment.)

4. Issues of “international competitiveness” are much more important than either economists or the Obama administration have been thinking. Excerpt:

…the mismeasurement problem obscures the growing globalization of the U.S. economy, which may in fact be the key trend over the past ten years. Policymakers look at strong productivity growth, and think they are seeing a positive indicator about the domestic economy. In fact, the mismeasurement problem means that the reported strong productivity growth includes some combination of domestic productivity growth, productivity growth at foreign suppliers, and productivity growth ”in the supply chain’. That is, if U.S. companies were able to intensify the efficiency of their offshoring during the crisis, that would show up as a gain in domestic productivity.

5. Read #4 directly above, think about who captures those gains, and you can see that the Mandel productivity hypothesis is broadly consistent with some of the data on income inequality.

6. There really is a structural unemployment problem and it stems from ongoing low productivity growth.

7. At the risk of sounding self-congratulatory, if you combine Mike’s estimates with the new Spence paper, and the reestimation for male median wages (down 28 percent since 1969), in my view the TGS thesis is looking stronger than it did even two months ago when the book was published.