Category: Web/Tech

Ask ChatGPT o1-preview, fiscal theory of the price level edition

Question: An economist once said that the fiscal theory of the price level was true, or became more true, as governments approached insolvency. But otherwise it is not true. Can you reconstruct analytically why the economist might have held this view?

The economist’s view hinges on the relationship between a government’s fiscal position and the determination of the price level, as articulated by the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL). The FTPL posits that the price level is determined by the government’s fiscal policy—specifically, the present value of its future primary surpluses relative to its outstanding debt—rather than solely by monetary factors such as the money supply.

Here’s an analytical reconstruction of why the economist might have held the view that the FTPL becomes more true as governments approach insolvency:

- Government’s Intertemporal Budget Constraint (GIBC):The GIBC states that the current real value of government debt (BB) must equal the present value of future primary surpluses (PV(S)PV(S)):B=PV(S)B = PV(S)This equation implies that the government must eventually generate enough primary surpluses (budget surpluses excluding interest payments) to repay its debt.

- Normal Circumstances—Solvent Government:

- When a government is solvent, it has the capacity to adjust its fiscal policy—by increasing taxes or reducing spending—to ensure that PV(S)PV(S) matches BB.

- In this scenario, the central bank’s monetary policy is the primary determinant of the price level. The government doesn’t need the price level to adjust to satisfy its budget constraint because it can adjust fiscal variables.

- The Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) or other monetary theories are more relevant here, linking the money supply and velocity of money to the price level.

- Approaching Insolvency—Fiscal Limitations:

- As a government approaches insolvency, its ability to generate sufficient future primary surpluses diminishes. It may face political, economic, or structural barriers to raising taxes or cutting spending.

- In this case, the GIBC cannot be satisfied through adjustments in fiscal policy alone.

- Price Level Adjustment Necessity:

- To satisfy the GIBC when PV(S)PV(S) is insufficient, the only remaining variable that can adjust is the price level (PP).

- An increase in the price level reduces the real value of nominal government debt (BB), effectively lowering the debt burden.

- This inflationary adjustment allows the GIBC to hold despite the government’s inability to generate adequate primary surpluses.

- Dominance of Fiscal Policy in Price Determination:

- When the government is near insolvency, fiscal considerations become paramount in determining the price level.

- Monetary policy may become subordinate or even impotent because the central bank might be compelled to accommodate the government’s fiscal needs (e.g., by monetizing debt).

- The FTPL becomes the relevant theory, as it explains how fiscal imbalances necessitate price level adjustments to satisfy the GIBC.

- Conclusion—Conditional Validity of the FTPL:

- Under normal, solvent conditions, the FTPL does not primarily determine the price level because the government can adjust fiscal policy, and monetary policy remains effective.

- As insolvency looms, fiscal constraints force reliance on price level adjustments, making the FTPL increasingly accurate in explaining inflation dynamics.

- Therefore, the economist argues that the FTPL becomes “more true” as a government approaches insolvency because fiscal limitations leave the price level as the main adjustment mechanism to restore fiscal balance.

Summary:

The economist believed that the FTPL’s applicability depends on the government’s fiscal health. In solvency, fiscal adjustments can maintain balance without affecting the price level, keeping monetary policy as the main determinant of inflation. Near insolvency, fiscal adjustments are constrained, necessitating price level changes to satisfy the government’s budget constraint—thus, the FTPL becomes more accurate in explaining the price level under these conditions.

Answer:

Because when a government is solvent, it can adjust taxes and spending to ensure its debts are covered, so fiscal policy doesn’t determine the price level—the central bank’s monetary policy does. But as a government nears insolvency and can’t generate enough future surpluses to repay debt, the only way to satisfy its budget constraint is through a higher price level (inflation reducing the real value of debt). So the fiscal theory of the price level becomes more applicable—the price level adjusts to ensure the real value of government debt equals the present value of future surpluses. Thus, the economist believed the fiscal theory is “more true” as governments approach insolvency because fiscal limitations force the price level to adjust to restore fiscal balance.

TC again: Here is the link to the chat. What percent of professional economists would have come up with a better answer? Here is an article on the o1 model beating the experts.

The dominance of large factor models in finance

This is less news to the private sector traders on the frontier, but the idea now has reached academia and the NBER working paper series:

We introduce artificial intelligence pricing theory (AIPT). In contrast with the APT’s foundational assumption of a low dimensional factor structure in returns, the AIPT conjectures that returns are driven by a large number of factors. We first verify this conjecture empirically and show that nonlinear models with an exorbitant number of factors (many more than the number of training observations or base assets) are far more successful in describing the out-of-sample behavior of asset returns than simpler standard models. We then theoretically characterize the behavior of large factor pricing models, from which we show that the AIPT’s “many factors” conjecture faithfully explains our empirical findings, while the APT’s “few factors” conjecture is contradicted by the data.

That is from a new paper by

My podcast with Brian Chau

I appear on his show, he describes it as follows:

Tyler Cowen: No Such Thing As Talent Decline

Here is the link.

Newsom vetoes AI bill

California Gov. Gavin Newsom has vetoed a controversial artificial-intelligence safety bill that pitted some of the biggest tech companies against prominent scientists who developed the technology.

The Democrat decided to reject the measure because it applies only to the biggest and most expensive AI models and leaves others unregulated, according to a person with knowledge of his thinking. Smaller models could prove just as problematic, and Newsom would prefer a regulatory framework that encompasses them all, the person added.

Had Newsom signed the bill into law, it would have laid the groundwork for how AI is regulated across the U.S., as California is home to the top companies in the industry. Proposals to regulate AI nationally have made little progress in Washington.

The governor is hoping to work with AI researchers and other experts on new legislation next year that could tackle in a more comprehensive way the same concerns of the bill he vetoed—about AI acting in ways its designers didn’t intend and causing economic or societal damage, the person with knowledge of his thinking said.

Here is more from the WSJ.

How tenure should be granted, circa 2024

Not just on the basis of what you publish, but on what you contribute to the major AI models. So if you go to a major archive and, in some manner, turn it into AI-readable form, that should count for a good deal. It is no worse than publishing a significant article, though of course depending on the quality of the archive. As it stands today, you basically would get no credit for that. You would instead be expected to turn the archive into articles or a book, even if that meant unearthing far less data for the AIs. Turning data into books takes a long time — is that always what humans should be doing?

Articles still count under this standard, as jstor seems to be in the literary “diet” of the major AI models. Wikipedia contributions should count for tenure, and any “hard for the AI to access data set” should count for all the more. Soon it won’t much matter whether humans read your data contribution, as long as the AIs do.

So we’re all going to do this, right? After all, “how much you really contribute to science” is obviously the standard we use, right? Right?

The Rapid Adoption of Generative AI

This paper reports results from the first nationally representative U.S. survey of generative AI adoption at work and at home. In August 2024, 39 percent of the U.S. population age 18-64 used generative AI. More than 24 percent of workers used it at least once in the week prior to being surveyed, and nearly one in nine used it every workday. Historical data on usage and mass-market product launches suggest that U.S. adoption of generative AI has been faster than adoption of the personal computer and the internet. Generative AI is a general purpose technology, in the sense that it is used in a wide range of occupations and job tasks at work and at home.

That is from a new paper by Alexander Bick, Adam Blandin, and David J. Deming, ungated copy here, blog post about it here.

Deep Learning for Economists

Deep learning provides powerful methods to impute structured information from large-scale, unstructured text and image datasets. For example, economists might wish to detect the presence of economic activity in satellite images, or to measure the topics or entities mentioned in social media, the congressional record, or firm filings. This review introduces deep neural networks, covering methods such as classifiers, regression models, generative AI, and embedding models. Applications include classification, document digitization, record linkage, and methods for data exploration in massive scale text and image corpora. When suitable methods are used, deep learning models can be cheap to tune and can scale affordably to problems involving millions or billions of data points. The review is accompanied by a regularly updated companion website, EconDL, with user-friendly demo notebooks, software resources, and a knowledge base that provides technical details and additional applications.

By Melissa Dell. And here is my earlier CWT with Melissa Dell.

Mercor

Mercor is solving global labor matching with models that understand human ability.

@mercor_ai raised a $30M Series A at a $250M valuation, led by @victoralazarte and @bgurley at @benchmark, with participation from @peterthiel, @jack, @adamdangelo, and @LHSummers.

Here is the tweet from Brendan Foody. My only tie to Mercor is that I was sitting next to someone on a plane from the company, we got to chatting, and I was very impressed. Here is a FAQ about the company and how it will vet talent using AI.

My Conversation with the excellent Tobi Lütke

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is the episode summary:

Tyler and Tobi hop from Germany to Canada to America to discuss a range of topics like how outsiders make good coders, learning in meetings by saying wrong things, having one-on-ones with your kids, the positives of venting, German craftsmanship vs. American agility, why German schooling made him miserable, why there aren’t more German tech giants, untranslatable words, the dividing line of between Northern and Southern Germany, why other countries shouldn’t compare themselves to the US, Canada’s lack of exports and brands, ice skating to work in Ottawa, how VR and AI will change retailing, why he expects to be “terribly embarrassed” when looking back at companies in the 2020s, why The Lean Startup is bad for retailers, how fantasy novels teach business principles, what he’s learning next, and more.

Excerpt:

COWEN: Are Canadians different in meetings than US Americans?

LÜTKE: Yes, as well. Yes, that’s true. It’s more on the side of American, definitely on a minimum quality bar. I think Canadians are often more about long term. I’ve seen Canadians more often think about what’s the next step after this step, but also just low ambition. That’s probably not the most popular thing to say around here, but Canada’s problem, often culturally, is a go-for-bronze mentality, which apparently is not uncommon for smaller countries attached to significantly more cultural or just bigger countries.

Actually, I found it’s very easy to work around. I think a lot of our success has been due to just me and my co-founder basically allowing everyone to go for world class. Everyone’s like, “Oh, well, if we are allowed to do this, then let’s go.” I think that makes a big difference. Ratcheting up ambition for a project is something that one has to do in a company in Canada.

COWEN: Is there something scarce that is needed to inject that into Canada and Canadians? Or is it simply a matter of someone showing up and doing it, and then it just all falls out and happens?

LÜTKE: I don’t know. Inasmuch as Shopify may be seen as something that succeeded, that alone didn’t do it. It would’ve been very, very nice if that would’ve happened. Now there’s another cohort of founders coming through. Some of them have been part of Shopify or come back from — I believe there are some great companies in Calgary, like NEO, that are more ambitious.

I think it’s a bit of a decision. The time it worked perfectly was when Canada was hosting the Winter Olympics, which is now a little bit of ancient history. There was actually a program Canada-wide that’s called Own the Podium. That makes sense. It’s home. We have more winter than most, so therefore let’s do well. And then we did. It’s just by far the best performance of Canada’s Olympic team of all times. I think to systematize it and make it stick — changing a culture is very, very difficult, but instances of just giving everyone permission to go for it have also been super successful.

And this:

COWEN: Say we compare Germany to the Netherlands, which is culturally pretty similar, very close to Koblenz. They have ASML, Adyen. Netherlands is a smaller country. Why have they done relatively better? Or you could cite Sweden, again, culturally not so distant from Germany.

LÜTKE: You’re asking very good questions that I much rather would ask you. [laughs] I don’t know. I wish I knew. I started at a small company in Germany; it didn’t do anything. So, it’s not like people didn’t do this. I came to Canada, again, this time it worked. Then I was head down for a very long time, building my thing because it was all-consuming, so I didn’t pay too much attention to — I wasn’t even very deliberate about where to start a company. I started in Ottawa because that’s where my wife and I were during the time she was studying there. We could find great talent there that was overlooked, it seemed, and gave everyone a project to be ambitious with, and it worked.

I think that if you create in geography a consensus that you’re a company really, really worth working for because it’s interesting work, great work, it might actually lead to something — then you can build it. I don’t quite understand why this is not possible to do in so many places in Germany because, again, Germany does have this wonderful appreciation of craftsmanship, which I think is actually underrepresented in software. I think it’s only recently — usually by Europeans — being brought up. Patrick Collison talks about it more and more, and certainly I do, too.

Making software is a craft. I think, in this way, Germany, Czech Republic, other places, Poland, are extremely enlightened in making this part of an apprenticeship system. I apprenticed as a computer programmer, and I thought it was exactly the right way to learn these things. Now, that means there’s, I believe, a lot of talent that then makes decisions other than putting it together to build ambitious startups. Something needs to be uncorked by the people who have more insight than I have.

COWEN: I think part of a hypothesis is that the Netherlands, and also Sweden, are somewhat happier countries than Germany. People smile more. At least superficially, they’re more optimistic. They’re more outgoing.

LÜTKE: I think it’s optimism.

COWEN: It’s striking to me that Germans, contrary to stereotype — I think they have a quite good sense of humor, but a lot of it is irony or somewhat black. Maybe that’s bad for tech. I wonder: people in the Bay Area — do they have a great sense of humor? I’m not sure they do. Maybe there’s some correlations across those variables.

Definitely recommended. Can you guess which is the one question Tobi refused to answer, for fear of being cancelled?

Scholars in support of the Moraes Brazil decision against X

Here is the link, in Portuguese, here is part of a Claude translation:

We, the undersigned, wish to express our deep concern about the ongoing attacks by Big Tech companies and their allies against Brazil’s digital sovereignty. The Brazilian judiciary’s dispute with Elon Musk is just the latest example of a broader effort to restrict the ability of sovereign nations to define a digital development agenda free from the control of mega-corporations based in the United States. At the end of August, the Brazilian Supreme Federal Court banned the X platform from Brazilian cyberspace for failing to comply with court decisions that required the suspension of accounts that instigated right-wing extremists to participate in riots and occupy the Legislative, Judicial, and Governmental palaces on January 8, 2023. Subsequently, President Lula da Silva made clear the Brazilian government’s intention to seek digital independence: to reduce the country’s dependence on foreign entities for data, AI capabilities, and digital infrastructure, as well as to promote the development of local technological ecosystems. In line with these objectives, the Brazilian state also intends to force Big Tech to pay fair taxes, comply with local laws, and be held accountable for the social externalities of their business models, which often promote violence and inequality.

These efforts have been met with attacks from the owner of X and right-wing leaders who complain about democracy and freedom of expression. But precisely because digital space lacks internationally and democratically decided regulatory agreements, large technology companies operate as rulers, deciding what should be moderated and what should be promoted on their platforms. Moreover, the X platform and other companies have begun to organize, along with their allies inside and outside the country, to undermine initiatives aimed at Brazil’s technological autonomy. More than a warning to Brazil, their actions send a worrying message to the world: that democratic countries seeking independence from Big Tech domination risk suffering disruptions to their democracies, with some Big Tech companies supporting far-right movements and parties.

The Brazilian case has become the main front in the evolving global conflict between digital corporations and those seeking to build a democratic and people-centered digital landscape focused on social and economic development. Technology companies not only control the digital world, but also lobby and operate against the public sector’s ability to create and maintain an independent digital agenda based on local values, needs, and aspirations. When their financial interests are at stake, they work happily with authoritarian governments. What we need is sufficient digital space for states to direct technologies by putting people and the planet ahead of private profits or unilateral state control.

All those who defend democratic values must support Brazil in its quest for digital sovereignty. We demand that Big Tech cease their attempts to sabotage Brazil’s initiatives aimed at building independent capabilities in artificial intelligence, public digital infrastructure, data governance, and cloud services. These attacks undermine not only the rights of Brazilian citizens but the broader aspirations of all democratic nations to achieve technological sovereignty. We also call on the Brazilian government to be firm in implementing its digital agenda and to denounce the pressures against it. The UN system and governments around the world should support these efforts.

Signed by Acemoglu, Zucman, Varoufakis, Cory Doctorow, Morozov, Mazzucato, Piketty, and many others. Somehow no one is talking about this petition and its embrace of censorship?

Via Pedro. And you will find some media coverage in Portuguese here.

China estimate and debate of the day

A major sign of Chinese economic malaise: In 2018, 51,302 new startups were founded in China. Last year, that number dropped to 1,202.

Here is one link, leading to others. Here is an attempt to talk down the relevance of those numbers. I would mention that initially there were far too many Chinese start-ups, in part because of government largesse, and so this change is not as bad as it sounds. Nonetheless it is bad.

Dean Ball on AI and prediction markets

What if an LLM read all my writing, listened to all my podcast appearances, and perhaps even to some of my private or semi-private conversations, and then placed hundreds of micro-bets for me, updating them as my own thinking evolved? What if LLMs did this for everyone who cares about AI, or any other topic? The income I would gain or lose needn’t be significant. If the bets were small, it could be a modest income stream, similar to what most artists get from streaming royalties, or what many mid-sized X accounts receive in revenue sharing. That way, any losses would not be the end of the world for most people. The real value would be the knowledge society could construct.

What if the debate over the capabilities trajectory of AI, for example, was also operationalized in 1000s of prediction markets, thickly traded in micro-bets made on behalf of millions?

And what if other LLMs also surveyed the broader media environment and placed their own bets? If you think of my writing and thinking (or yours) as a kind of one-man intellectual hedge fund, these latter groups would be something like funds of funds.

What if we could simulate financial markets for every question about the future that concerns us? And what if it cost next to nothing to do? What if, after the work of setting it up was complete, all this just carried on each day, in a way that few humans had to devote much time to maintaining or thinking about?

Here is the full piece.

“four percent of humanity subscribes to OnlyFans” (from my email)

Andrew Cedotal writes me:

This issue came up with the post where someone claimed that N% of Americans were active OnlyFans content creators, here it is again!

For software services, total accounts ever created is a vanity metric. It’s not used by serious operators or investors of consumer-tech companies (the fact that it shows up in public financial reports so often thus has interesting implications).

The social impact/business value of a software service is about flow (e.g. monthly active users and monthly revenue), not stock. 100 real human signups means many, many fewer actual monthly active users (MAU) at any point, because users churn out. Even the best-retaining services around (e.g. Snap) only have 90% yearly retention, which then compounds downward.

Then there’s the issue that for any public software service, many accounts are bots, throwaways, people who forgot their password, etc.

Rather than make a truly wild guesstimate, let’s look at a frontier based on the report of $6.6B gross payments made by users in 2023 (so average revenue / month is $0.55B). All of the following are possible points on the frontier of paying MAU (paying monthly active users) vs. monthtly APPPU (monthly payments per paying user):

* 10 million paying MAU, $55 monthly APPPU

* 30 million paying MAU, $18.33 monthly APPPU

* 50 million paying MAU, $11 monthly APPPU

* 100 million paying MAU, $5.5 monthly APPPU(Industry standard is to look at ARPPU–average revenue per paying user–and not average payments, but I think here we’re more interested in determining how much money users are putting into it and ignoring platform take rate, not a financial analysis of the company.)

Now, OnlyFans might have ~300M total signups ever, but let’s assume half of those are dupes and bots. So 150M real human signups. It’s unlikely that more than 20% of people who have ever created an account have ever entered a credit card, so that’s 300 * 0.5 * .2 = 30M as a cap on people who have ever paid. Take into account userbase churn, and a guess is ~12M monthly paying accounts right now (0.15% of humanity, not 4%), which would put them at $45.83 monthly APPPU or a yearly APPPU of ~$550. About the annual cost of a gym membership in the U.S.

Strawberry Alarm Clock!

Deep Prasad writes:

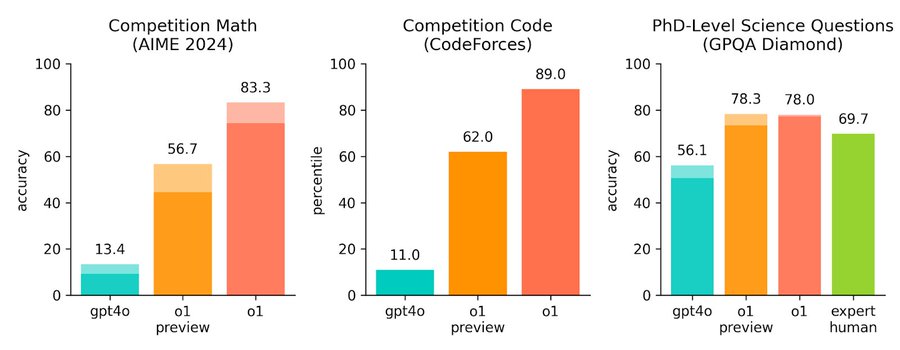

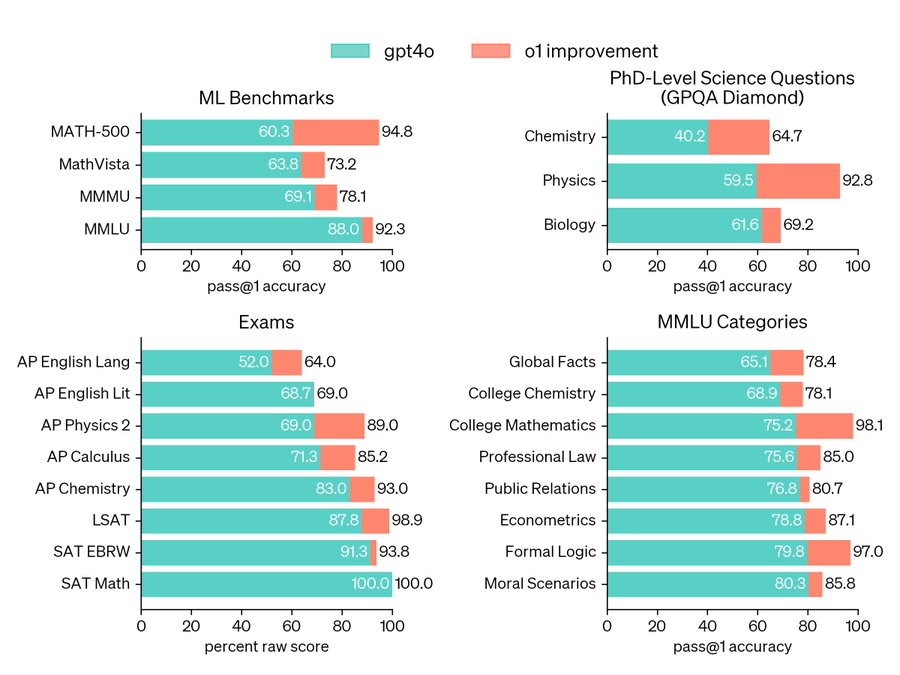

OpenAI just released an AI as smart as most PhDs in physics, mathematics and the life sciences. Wake up. The world will never be the same and in many ways, it will be unrecognizable a decade from now.

Mckay Wrigley is enthusiastic:

o1’s ability to think, plan, and execute is off the charts.

Ethan Mollick says:

There are a lot of milestones that AI passed today. Gold medal at the Math Olympiad among them.

Like Ethan, however, I agree the model is not necessarily better at a lot of non-reasoning tasks. Ethan also notes that AGI will be jagged and uneven.

Subbarao makes guesses as to how it works. Here is some other guy saying a bunch of stuff. And yet further commentary.

Whatever you think of those specific claims, there is a lot of room, as with the John Lennon “Strawberry Fields Forever” demo, to get a lot better yet. For one thing, it can think for longer yet! Whole new doors have been opened, and if you are reading some lukewarm commentary that is probably what the person does not grasp. It is the people who think “…if they can do this…” who have been most successful in predicting the course of AI.

Shital Shah remarks:

This is truly a game changer and step change. It takes us out of slow progress constrained by compute capital and training tokens to rather open world where time is the only limit.

I would love to have one of these (with some tweaks) as my agent.

Taelin claims AGI is achieved. Here is the closest Gary Marcus ever will come to eating crow. Here is how I would troll OpenAI.

Meanwhile, the status of people who do energy policy is due to rise.

Brian Chau recommends it for looking up citations.

Matt Clifford says “crosswords!”

“Model this!”, he demanded of the new fruit. That is Benjamin Manning, economics graduate student at MIT. He got his wish.

Is it “It’s happening!”, or rather “It has happened!”?

Here is another song by Strawberry Alarm Clock, sadly no one got the reference the first time around. It is from the album “Wake Up, It’s Tomorrow”…

Addendum: For context and background, my two previous introductory posts are here and here.

OpenAI announces “Strawberry”

From the great Noam Brown, the link to the more detailed OpenAI page is here. And a preview page here. Step by step advanced reasoning, now a reality, with some pretty incredible benchmark achievements. Too much to say, right?

Here is the accompanying John Lennon demo.