Headlines

As Price of Lead Soars, British Churches Find Holes in Roof

It is described as the most serious assault on British churches since the Reformation; the roofs of course are made partly of lead. And here are stories from the U.S. In some cases entire neighborhoods are being rendered uninhabitable by the boom in commodities prices and the induced theft.

More on Bartels

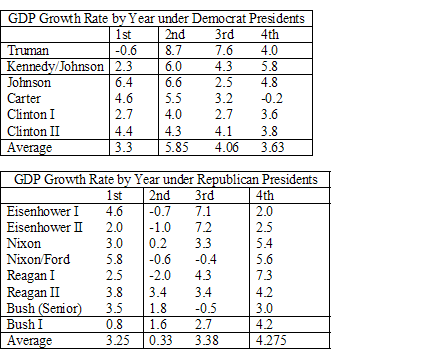

I’m a little surprised that the Bartels result is receiving so much attention because the result, in slightly different form, has long been known to political economists under the rubric of partisan business cycle theory. In a nutshell, the theory of partisan business cycles says that Democrats care more about reducing unemployment, Republicans care more about reducing inflation. Wage growth is set according to expected inflation in advance of an election. Since which party will win the election is unknown wages growth is set according to a mean of the Democrat (high) and Republican (low) expected inflation rates. If Democrats are elected they inflate and real wages fall creating a boom. If Republicans are elected they reduce inflation and real wages rise creating a bust. Notice that in PBC theory neither party creates a boom or bust it’s uncertainty which drives the result – if the winning party were known there would be neither boom nor bust.

Ok, there’s plenty to question about the theory but let’s look at the data.

Notice that in the second year of just about every Democratic Presidency there is a boom. Interestingly, the boom is biggest for Truman whose reelection was highly uncertain (remember Dewey wins!) thus expected inflation would have been low and the boom big. Similarly the boom is smallest (relative to the surrounding years) for Clinton II a relatively certain reelection.

Now look at Republicans in just about every second year of a Republican Presidency there is a bust. The one major exception being Reagan II where uncertainty about the outcome was low.

It’s pretty clear that this result can explain Bartels’s result which is exactly Tyler’s point in his post. It’s equally clear that when we consider Presidents there aren’t many data points. (PBC does appear to hold somewhat in other countries).

Notice that the reason for the result, according to PBC, is sticky wages and the business cycle and not some nefarious story about taxes, oligarchies and political conspiracies.

Haitian prison

If international minimum standards of about four square metres for

every prisoner were met, the National Penitentiary would hold a little

more than 400 inmates. On the day Maclean’s visits the prison, there

are 3,331 men jailed inside. Most, at least 90 per cent, have not had a

trial. They are held under the euphemistic term "preventative

detention," and because of a lack of judges, proper evidence, and even

vehicles to transport them to court, it is unlikely many will be tried

any time soon.

"People sleep on top of people in here," one prisoner says through

the bars of a bathroom-sized cell that holds 43 people. Most are

standing. Others have fashioned hammocks out of scraps of cloth and

have suspended themselves from the bars of the cell’s high window,

where they can get more light and air…

Here is more. And that is not all:

There is a punishment cell, perhaps four feet tall, where no one can

stand. The punishment cell is crowded, but less so than other cells,

and some inmates prefer it. "You have people who do things wrong just

so they have a place to lie down or to be safe from gangs," Cadet says.

Here is a video about recent food riots in Haiti, and no those are not in the prisons.

Assorted links

2. The demise of the semi-colon?

3. Jason Furman on fixing our fiscal problems

4. More proposals for limiting chess draws

Larry Bartels, and how Republican Presidents drive income inequality

He writes:

In any case, the largest partisan differences in income growth, by far, occur in the second year of each administration.

The link, by the way, answers many objections to his basic thesis. View this graph if you don’t already know the argument. The core claim is that Republican Presidents are better for the rich and Democratic Presidents are better for the poor, and to a striking degree.

I view the statistical significance of the Bartels result as stemming from monetary policy. Republicans are more willing to break the back of inflation and risk an immediate recession. Alternatively, it could be said that central bankers expect enough support for tough, anti-inflation decisions only from Republican Presidents. (Note that Jimmy Carter, who did support Volcker, is in fact the single Democratic outlier.) Note that without the monetary policy effect, only a few data points, mostly from very recent times, support the basic claim. Without the monetary policy effect, I do not think that statistical significance would remain. Furthermore other plausible channels for income inequality effects, such as tax and regulatory decisions, would not be concentrated in the second year of each administration. Monetary policy decisions would be. A recession, by generating more unemployment, hurts the poor the most in proportional terms.

So what does this all mean?

Inflation is good for the poor in the short run, since many poor are debtors. But inflation is bad for the poor in the long run. Just ask anyone who lived through the New Zealand inflation of the 1970s.

So Bartels could have entitled his key graph: "Democratic Presidents live for the short run and we need a Republican President every now and then."

Addendum: Even Paul Krugman wonders about the basic mechanism driving the result.

World Wide Losses are the Best Losses

From the frozen lands of Norway’s Arctic Circle to the hot sands of the Middle East and the booming metropolis of Shanghai the losses from America’s subprime crisis are popping up around the world like angry whac-a-moles. The losses are large and appear larger by being found in the most unexpected of places. Today the focus is on these world-wide losses but I think future historians will focus on how the crisis demonstrated to everyone the power of integrated capital markets to diversify risk.

The losses, of course, are regrettable and the desire to find and apportion blame for the crisis among investors, home buyers, mortgage brokers, credit analysts and regulators is understandable. We should and will learn lessons. And yet, despite problems with transparency one of those lessons ought to be that the crisis would have been worse if the losses had been more concentrated.

From this perspective, world-wide losses are perhaps the best losses of all.

How free trade affects thievery, part II

Yes commodity prices are high:

A thief sneaked under the sport utility vehicle with a battery-powered

saw, slicing from the Toyota’s underbelly what may be one of the most

expensive small parts of the auto world: the catalytic converter, an

essential emissions-control device made with small amounts of metals

more precious than gold. Who knew?…Theft of scrap metals like copper and aluminum has been common here and

across the country for years, fueled by rising construction costs and

the building boom in China. But now thieves have found an easy payday

from the upper echelon of the periodic table. It seems there may not be

an easier place to score some platinum than under the hood of a car…The catalytic converter is made with trace amounts of platinum,

palladium and rhodium, which speed chemical reactions and help clean

emissions at very high temperatures. Selling stolen converters to scrap

yards or recyclers, a thief can net a couple of hundred dollars apiece.

Here is the story. Here is part I in the series. Here is a man who died trying to extract gold from his computer.

The erotics of investing

When young men were shown erotic pictures, they were more likely to

make a larger financial gamble than if they were shown a picture of

something scary, such as a snake, or something neutral, such as a

stapler, university researchers reported.The arousing pictures lit up the same part of the brain that lights up when financial risks are taken.

…The study conforms with recent research that indicates men shown a

pornographic movie were more likely to make riskier sexual decisions.

Another suggests straight men think less about their financial future

after being shown pictures of pretty women.

Here is more. One question — and perhaps a more direct test of the hypothesis — is whether traders in more sexually integrated firms do in fact behave differently. Or how about companies located next to modeling agencies? I suspect in real social settings the effect washes out, for reasons identified by Freud (among others) some time ago. The more literally minded among us might also question whether a stapler is in fact a neutral image. It isn’t for me.

Jeff Sachs on biodiversity

His new book Common Wealth devotes an entire chapter to this important topic. Sachs writes:

The main lesson of ecology is the interconnectedness of the various parts of an ecosystem and the dangers of abrupt, nonlinear, and even catastrophic changes caused by modest forcings…It is a basic finding that biological diversity increases the productivity and resilience of ecosystems. With more species filling more niches in a given location, a biodiverse ecosystem is better buffered against external shocks in is more adept at cycling nutrients, capturing solar radiation, utilizing water resources, and preventing the takeover of the system by single predators, weeds, or pathogens. In other words, preserving biodiversity helps to preserve all aspects of ecosystem functions. Removing one or more species from an ecosystem, for example, by selective harvesting of trees or fish or hunted animals, can lead to a cascade of ecological changes with large, adverse, and nonlinear effects on the functioning of the ecosystem.

Now, loyal MR readers may remember that I am genuinely uncertain how much we should worry about the loss of biodiversity. I do know the following:

1. Many smart people who know much more science than I do are very worried about the loss of biodiversity.

2. Given that the human population has ballooned for the foreseeable future, massive losses in biodiversity are inevitable. The question is how bad the marginal losses will be, if we do not adapt policy accordingly.

3. If I had to conduct a debate and argue that the marginal loss of biodiversity was going to be a tragedy for human beings (obviously, I can see the loss to animals, and yes I do count that for something), I would not do very well. Yes Yana’s children won’t eat tuna and then I would sputter something about carbon and nitrogen cycles.

So OK readers, help me out. I’ve read Sachs’s passage and I don’t think I disagree with any of the claims in it. But I still cannot articulate to a skeptic exactly what marginal disaster will come if we do not take drastic action to preserve biodiversity.

Please use the comments to set me straight. What exactly will go wrong? And do not compare seven billion humans to pristine nature. Compare seven billion humans with bad biodiversity policy to, say, five billion humans with a pretty good biodiversity policy. What exactly is the difference? What are these costs as a percentage of gdp?

Please be as specific as possible; I genuinely would like to learn more.

Car patrol vs. foot patrol

Car patrol eliminated the neighborhood police officer. Police were pulled off neighborhood beats to fill cars. But motorized patrol — the cornerstone of urban policing — has no effect on crime rates, victimization, or public satisfaction. Lawrence Sherman was an early critic of telephone dispatch and motorized patrol, noted, "The rise of telephone dispatch transformed both the method and purpose of patrol. Instead of watching to prevent crime, motorized police patrol became a process of merely waiting to respond to crime."

That is from Peter Moskos’s Cop in the Hood: My Year Policing Baltimore’s Eastern District; here is my previous post on the book.

Why economics was late in starting

I’ve already posed the question, I’d like to add two points. First, sustained economic growth in the Western world starts in 17th century England, as shown by Greg Clark. Interest in economic reasoning then comes rapidly, first from the mercantilists, then in Adam Smith and some earlier free trade thinkers, such as Dudley North and Nicholas Barbon.

Second, the idea of "private vices, publick virtues" was central for eighteenth century economic thought and for social science more generally. This came from Bernard Mandeville (drawing upon the French Jansenists) in 1720. It’s no accident that Mandeville lived in the Dutch Republic, which had very little censorship. No, I am not a Straussian but the merits of that viewpoint are often overlooked.

The School of Salamanca had an excellent marginal utility theory in 17th century Spain, the framework simply did not go anywhere. For that matter we can look later and see that Samuel Bailey, Mountifort Longfield (1834), and others had critical components of Marshall. But no one really cared because they could not yet see how important those contributions would turn out to be. This is a central theme in why the growth of economic thought took so long.

It also suggests that today we might have some very important ideas amongst us, we simply cannot yet see how fruitful they will be. Their own proponents may not even know it.

Assorted links

2. Satire of a Tyler Cowen book review, via Bamber

3. Japanese barcodes, via David Zetland

4. Leonhard Euler, via www.geekpress.com

Predictions about 2008

A typical vacation in 2008 is to spend a week at an undersea resort,

where your hotel room window looks out on a tropical underwater reef, a

sunken ship or an ancient, excavated city. Available to guests are two-

and three-person submarines in which you can cruise well-marked

underwater trails.

But many of the predictions are good, at least in part. Get this:

The single most important item in 2008 households is the computer.

These electronic brains govern everything from meal preparation and

waking up the household to assembling shopping lists and keeping track

of the bank balance. Sensors in kitchen appliances, climatizing units,

communicators, power supply and other household utilities warn the

computer when the item is likely to fail. A repairman will show up even

before any obvious breakdown occurs.Computers also handle travel reservations, relay telephone messages,

keep track of birthdays and anniversaries, compute taxes and even

figure the monthly bills for electricity, water, telephone and other

utilities. Not every family has its private computer. Many families

reserve time on a city or regional computer to serve their needs. The

machine tallies up its own services and submits a bill, just as it does

with other utilities.

Via www.geekpress.com. As usual, it is presumed that traffic and transportation problems will have seen a lot of progress when in fact they have not. Nor was it understood how unevenly the benefits of progress would be distributed and how possible it would be to continue a life basically devoid of these advances.

Capital requirements smackdown watch

Eric Falkenstein writes:

How much capital for derivatives? Good question. Should it be weighted by risk? If so, how does one measure risk? Considering that risk is a function of the collateral, which comes in many different flavors (traded debt, pools of mortgages, pools of bank lines), and then are structured very differently, with differing levels of subordination, differing rules for the waterfalls of cashflows depending on various metrics of collateral quality. It’s a mess.

…You may think this is no different than regular lending, but you would be wrong. For example, lets say you have two swaps, but they both offset each other almost exactly for interest rate risk, but as they have different counterparties, they have differing credit risk. How about swaps from the same counterparty, but differing interest rate exposures, partially netted. How much should capital be netted? And if the US banks have capital requirements greater than economically necessary, how many seconds before all swaps would move offshore?

I take him to be saying that financial institutions can never be transparent in their risk-taking, or at least not in the sense that can be made accountable to a regulator. Read the whole thing. Read also Doug Colkitt’s comment here. Note by the way that Bear Stearns, at the time of its collapse, had met Basel capital requirements.

Mark Thoma writes:

I’d argue that even though Basel was not perfect it was much better than having no regulation at all…If the regulations under Basel caused banks to move assets off the books, then without regulation they wouldn’t have needed to move them, but the assets still could have been used in the same way, financial institutions could have taken the same risks and would have had the same or more incentive to do so without regulatory oversight, and they could have caused the same troubles. I don’t see how the regulations themselves caused the risk taking. Regulation caused evasion of regulation, and Basel II is trying to deal with that problem, but the regulations did not cause the risk-taking itself.

Currently my view is closer to Thoma’s. The case against regulation requires that derivatives risk is observable (by the bank itself, and of course if it is not observable to anyone run the other way!) but not verifiable to an outside regulator (otherwise it could be controlled by regulation). Even in that case, however, more informal systems of regulation should work, albeit imperfectly. Yes banks will sometimes lie and trick the regulators but at least another layer of protection is in place.

There’s lot of talk about the government buying up mortagages. Even if you favor that plan, it’s a one-off measure, not a long-term solution to stop a future crisis. There is in fact a paucity of good regulatory proposals on the table. There are plenty of ideas for how to stop what went wrong "last time" but fewer good ideas for how to stop the next version of a financial crisis.

The future of economics

In a nutshell, foreigners and empirical work:

This short paper collects and studies the CVs of 112 assistant professors in the top-ten American departments of economics. The paper treats these as a glimpse of the future. We find evidence of a strong brain drain. We find also a predominance of empirical work.

Three-quarters of the bachelor degrees were obtained from abroad. Macro, econometrics, and labor economics are the most popular fields, see p.8 for the full list. Here is the paper, hat tip to Pluralist Economics Review.