It Wasn’t Me

As finance minister, Mr Cowen was responsible for a startling 13 per cent rise in government spending last year, which turned a budget surplus of 2.9 per cent of gross domestic product in 2006 into a forecast deficit of 1.2 per cent this year.

“It was an election year, but if you increase spending that much, you will make some mistakes,” says Alan Barrett, senior economist at Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute.

“I do not think anyone would say from the state of public services that it was worth it.”

Cowen is now confirmed as Irish prime minister, here is one story.

Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow America

That’s the subtitle, the title is Bound for Freedom and it is by Douglas Flamming. This book is a good antidote to libertarians who assign too much blame to state governments, and not enough blame to voluntary norms, when it comes to Southern segregation and Jim Crow. Early in the twentieth century, Los Angeles was devoid of the oppressive Jim Crow laws that were so common in the South. In fact California had some (unenforced) laws prohibiting discrimination according to race. Yet according to one survey only three of two hundred saloons would serve blacks. Most hotels did not accept blacks either and that was in direct contradiction to state law. Both Hollywood and the petroleum industry for the most part refused to hire blacks, even for jobs of unskilled labor. On the positive side, many of the businesses along Central Avenue were fully integrated, serving Latino and Japanese customers as well. Blacks did have, overall, a much better existence in LA than in the South but this volume shows that Jim Crow cannot simply be blamed on oppressive government regulations.

Here is my earlier post on Jim Crow in sports.

Antiquity was richer than we think

George Grantham writes:

In recent decades the conventional dating of the origins of Western Europe’s economic ascendancy to the tenth and eleventh centuries AD has been called in question by archaeological findings and reinterpretations of the early medieval texts indicating significantly higher levels of material prosperity in Antiquity than conventional accounts consider plausible. On the basis of that evidence it appears likely that at its peak the classical economy was almost as large as that of Western Europe on the eve of the Industrial Revolution.

Here is sixty pages more, noting that every single page of this paper has interesting material, a remarkable achievement. Here is one bit:

Between 1300 and 900 BC three innovations turned out to be crucial for the eventual integration of Europe’s economic space. The earliest was the improvement in ship construction and sailing technique. As will be discussed in more detail below, the decisive changes in rigging and hull construction that permitted larger and more robust ships were achieved before the Aegean collapse in response to the growing bulk trade in timber and agricultural produce. The perfection of ferrous metallurgy by Cypriot and Aegean smiths was the second decisive innovation. Unlike the changes in naval architecture, the metallurgical innovations of the Aegean Dark Age were an unexpected by-product of economic collapse. The third major development affecting the later expansion of trading networks was the transformation of Proto-Canaanite syllabaries into a true alphabet consisting of approximately two dozen phonetic signs. The triumph of the alphabet was also a consequence of the Aegean collapse, which destroyed the earlier and slightly more cumbersome cuneiform script employed to document administrative and commercial transactions outside Egypt.

The pointer is from Razib. Here is Grantham on the agricultural revolution.

The burdens of fame

Germany’s celebrity polar bear Knut has triggered a new controversy

by fishing out 10 live carp from his moat and killing them in front of

visitors. Critics say Berlin Zoo should not have put live fish inside Knut’s enclosure…The Frankfurter Allgemeine news website reports that Knut "senselessly

murdered the carp", fishing them out, playing with them and then

leaving the remains.

And it seems that the Green Party has complained. Um….HE’S A POLAR BEAR!

Addendum: The story is here. You can survey the German-language press here. The FAZ article is here. While I can imagine valid criticisms of zoos, this is not one of them. It also should be noted that Knut’s normal diet does not consist of tofu.

Assorted Links

- Keith Chen (of monkey sex fame) says cognitive dissonance may be an artifact of an unappreciated Monty Hall problem.

- Brad DeLong is an "optimist" on housing. Even if wrong this puts him in good company.

- The economics of Barack Obama Senior is upsetting some people.

Why is monogamy associated with economic development?

Eric Gould, Omer Moav and Avi Simhon offer a new answer in the March 2008 American Economic Review: female inequality. Economic growth means that some women have higher human capital than others and thus they are better suited at producing and rearing high quality children. Wealthy men with lots of human capital will start to bid for these women and they will have to offer them exclusive status; these men also wish to invest in a smaller number of higher quality children.

In other words, male inequality encourages polygamy while female inequality discourages it. Apparently female inequality has been winning that race.

The hypothesis also helps explain why polygamy unravels so decisively at some point. Since monogamy itself encourages children (including daughters) with higher human capital, initial tendencies toward monogamy are self-reinforcing.

Here is an earlier ungated version of the paper. Or buy the new version here for $7.50. Here are previous MR posts on polygamy.

Headlines

As Price of Lead Soars, British Churches Find Holes in Roof

It is described as the most serious assault on British churches since the Reformation; the roofs of course are made partly of lead. And here are stories from the U.S. In some cases entire neighborhoods are being rendered uninhabitable by the boom in commodities prices and the induced theft.

More on Bartels

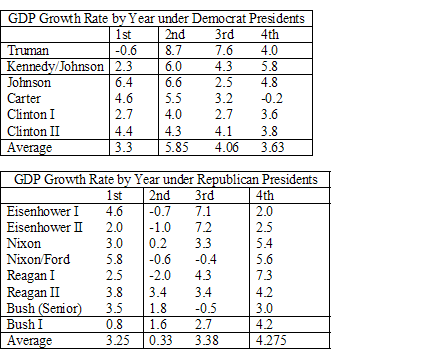

I’m a little surprised that the Bartels result is receiving so much attention because the result, in slightly different form, has long been known to political economists under the rubric of partisan business cycle theory. In a nutshell, the theory of partisan business cycles says that Democrats care more about reducing unemployment, Republicans care more about reducing inflation. Wage growth is set according to expected inflation in advance of an election. Since which party will win the election is unknown wages growth is set according to a mean of the Democrat (high) and Republican (low) expected inflation rates. If Democrats are elected they inflate and real wages fall creating a boom. If Republicans are elected they reduce inflation and real wages rise creating a bust. Notice that in PBC theory neither party creates a boom or bust it’s uncertainty which drives the result – if the winning party were known there would be neither boom nor bust.

Ok, there’s plenty to question about the theory but let’s look at the data.

Notice that in the second year of just about every Democratic Presidency there is a boom. Interestingly, the boom is biggest for Truman whose reelection was highly uncertain (remember Dewey wins!) thus expected inflation would have been low and the boom big. Similarly the boom is smallest (relative to the surrounding years) for Clinton II a relatively certain reelection.

Now look at Republicans in just about every second year of a Republican Presidency there is a bust. The one major exception being Reagan II where uncertainty about the outcome was low.

It’s pretty clear that this result can explain Bartels’s result which is exactly Tyler’s point in his post. It’s equally clear that when we consider Presidents there aren’t many data points. (PBC does appear to hold somewhat in other countries).

Notice that the reason for the result, according to PBC, is sticky wages and the business cycle and not some nefarious story about taxes, oligarchies and political conspiracies.

Haitian prison

If international minimum standards of about four square metres for

every prisoner were met, the National Penitentiary would hold a little

more than 400 inmates. On the day Maclean’s visits the prison, there

are 3,331 men jailed inside. Most, at least 90 per cent, have not had a

trial. They are held under the euphemistic term "preventative

detention," and because of a lack of judges, proper evidence, and even

vehicles to transport them to court, it is unlikely many will be tried

any time soon.

"People sleep on top of people in here," one prisoner says through

the bars of a bathroom-sized cell that holds 43 people. Most are

standing. Others have fashioned hammocks out of scraps of cloth and

have suspended themselves from the bars of the cell’s high window,

where they can get more light and air…

Here is more. And that is not all:

There is a punishment cell, perhaps four feet tall, where no one can

stand. The punishment cell is crowded, but less so than other cells,

and some inmates prefer it. "You have people who do things wrong just

so they have a place to lie down or to be safe from gangs," Cadet says.

Here is a video about recent food riots in Haiti, and no those are not in the prisons.

Assorted links

2. The demise of the semi-colon?

3. Jason Furman on fixing our fiscal problems

4. More proposals for limiting chess draws

Larry Bartels, and how Republican Presidents drive income inequality

He writes:

In any case, the largest partisan differences in income growth, by far, occur in the second year of each administration.

The link, by the way, answers many objections to his basic thesis. View this graph if you don’t already know the argument. The core claim is that Republican Presidents are better for the rich and Democratic Presidents are better for the poor, and to a striking degree.

I view the statistical significance of the Bartels result as stemming from monetary policy. Republicans are more willing to break the back of inflation and risk an immediate recession. Alternatively, it could be said that central bankers expect enough support for tough, anti-inflation decisions only from Republican Presidents. (Note that Jimmy Carter, who did support Volcker, is in fact the single Democratic outlier.) Note that without the monetary policy effect, only a few data points, mostly from very recent times, support the basic claim. Without the monetary policy effect, I do not think that statistical significance would remain. Furthermore other plausible channels for income inequality effects, such as tax and regulatory decisions, would not be concentrated in the second year of each administration. Monetary policy decisions would be. A recession, by generating more unemployment, hurts the poor the most in proportional terms.

So what does this all mean?

Inflation is good for the poor in the short run, since many poor are debtors. But inflation is bad for the poor in the long run. Just ask anyone who lived through the New Zealand inflation of the 1970s.

So Bartels could have entitled his key graph: "Democratic Presidents live for the short run and we need a Republican President every now and then."

Addendum: Even Paul Krugman wonders about the basic mechanism driving the result.

World Wide Losses are the Best Losses

From the frozen lands of Norway’s Arctic Circle to the hot sands of the Middle East and the booming metropolis of Shanghai the losses from America’s subprime crisis are popping up around the world like angry whac-a-moles. The losses are large and appear larger by being found in the most unexpected of places. Today the focus is on these world-wide losses but I think future historians will focus on how the crisis demonstrated to everyone the power of integrated capital markets to diversify risk.

The losses, of course, are regrettable and the desire to find and apportion blame for the crisis among investors, home buyers, mortgage brokers, credit analysts and regulators is understandable. We should and will learn lessons. And yet, despite problems with transparency one of those lessons ought to be that the crisis would have been worse if the losses had been more concentrated.

From this perspective, world-wide losses are perhaps the best losses of all.

How free trade affects thievery, part II

Yes commodity prices are high:

A thief sneaked under the sport utility vehicle with a battery-powered

saw, slicing from the Toyota’s underbelly what may be one of the most

expensive small parts of the auto world: the catalytic converter, an

essential emissions-control device made with small amounts of metals

more precious than gold. Who knew?…Theft of scrap metals like copper and aluminum has been common here and

across the country for years, fueled by rising construction costs and

the building boom in China. But now thieves have found an easy payday

from the upper echelon of the periodic table. It seems there may not be

an easier place to score some platinum than under the hood of a car…The catalytic converter is made with trace amounts of platinum,

palladium and rhodium, which speed chemical reactions and help clean

emissions at very high temperatures. Selling stolen converters to scrap

yards or recyclers, a thief can net a couple of hundred dollars apiece.

Here is the story. Here is part I in the series. Here is a man who died trying to extract gold from his computer.

The erotics of investing

When young men were shown erotic pictures, they were more likely to

make a larger financial gamble than if they were shown a picture of

something scary, such as a snake, or something neutral, such as a

stapler, university researchers reported.The arousing pictures lit up the same part of the brain that lights up when financial risks are taken.

…The study conforms with recent research that indicates men shown a

pornographic movie were more likely to make riskier sexual decisions.

Another suggests straight men think less about their financial future

after being shown pictures of pretty women.

Here is more. One question — and perhaps a more direct test of the hypothesis — is whether traders in more sexually integrated firms do in fact behave differently. Or how about companies located next to modeling agencies? I suspect in real social settings the effect washes out, for reasons identified by Freud (among others) some time ago. The more literally minded among us might also question whether a stapler is in fact a neutral image. It isn’t for me.

Jeff Sachs on biodiversity

His new book Common Wealth devotes an entire chapter to this important topic. Sachs writes:

The main lesson of ecology is the interconnectedness of the various parts of an ecosystem and the dangers of abrupt, nonlinear, and even catastrophic changes caused by modest forcings…It is a basic finding that biological diversity increases the productivity and resilience of ecosystems. With more species filling more niches in a given location, a biodiverse ecosystem is better buffered against external shocks in is more adept at cycling nutrients, capturing solar radiation, utilizing water resources, and preventing the takeover of the system by single predators, weeds, or pathogens. In other words, preserving biodiversity helps to preserve all aspects of ecosystem functions. Removing one or more species from an ecosystem, for example, by selective harvesting of trees or fish or hunted animals, can lead to a cascade of ecological changes with large, adverse, and nonlinear effects on the functioning of the ecosystem.

Now, loyal MR readers may remember that I am genuinely uncertain how much we should worry about the loss of biodiversity. I do know the following:

1. Many smart people who know much more science than I do are very worried about the loss of biodiversity.

2. Given that the human population has ballooned for the foreseeable future, massive losses in biodiversity are inevitable. The question is how bad the marginal losses will be, if we do not adapt policy accordingly.

3. If I had to conduct a debate and argue that the marginal loss of biodiversity was going to be a tragedy for human beings (obviously, I can see the loss to animals, and yes I do count that for something), I would not do very well. Yes Yana’s children won’t eat tuna and then I would sputter something about carbon and nitrogen cycles.

So OK readers, help me out. I’ve read Sachs’s passage and I don’t think I disagree with any of the claims in it. But I still cannot articulate to a skeptic exactly what marginal disaster will come if we do not take drastic action to preserve biodiversity.

Please use the comments to set me straight. What exactly will go wrong? And do not compare seven billion humans to pristine nature. Compare seven billion humans with bad biodiversity policy to, say, five billion humans with a pretty good biodiversity policy. What exactly is the difference? What are these costs as a percentage of gdp?

Please be as specific as possible; I genuinely would like to learn more.