Why no battling gods?

Troy, the movie version of Homer’s The Iliad, is out today. Here is one report, from the May 14 Entertainment Weekly:

While Pitt’s character got tweaked, the rest of The Iliad went pretty darn Hollywood. Briseis, a slave girl captured by the Greeks — speechless in Homer’s tale — becomes a royal priestess and love interest for Achilles…More notably, no gods interfere with battles in Troy. “I didn’t want them in,” says screenwriter Benioff.

The screenwriter notes that activist gods would make the movie too much like The Clash of the Titans. My rhetorical question for the day is why clashing polytheistic gods make for a less broadly saleable story than do human heroes. And does this help explain why monotheistic religions have been growing at the expense of polytheism for some time now?

Thanks to Yana for the pointer to the EW article.

The Train from Nowhere

New book, 233 pages, quite dull, no economics. French of course. More here.

Prices versus Costs

Why do we favor free trade? Is it because prices are lower in other countries? No. It’s because costs of production are lower in other countries. Prices and costs are not the same.

Consider, for example, the issue of drug reimportation. Why do politicians and some consumers want to reimport drugs from other countries? Is it because costs of production are lower in other countries? No. It’s because prices are lower in other countries. Once one realizes this it should become obvious why drug reimportation is not “free trade” and promises little or no net benefits – drug reimportation doesn’t lower costs and thus there are few efficiency gains to be had by reimportation.

Addendum: A more complete analysis of reimportation would look at the effects on consumption (slight increase in the US, potentially large reduction in the “exporting” countries) and the effects on innovation (reduced).

Outsourcing: the death of us all?

Wherein lie the limits to outsourcing?

[German] families have to pay for either a cemetery plot or for cremation. Here, too, Woite has found a way to avoid the high price Germany’s cities and towns charge for such services. He sends corpses for cremation to the neighboring Czech Republic, where costs are significantly lower. Or customers can have their deceased buried in a Czech cemetery.

Three times a week Woite’s employees drive back and forth between Germany and the Czech Republic. And although German law requires corpses and ashes to be kept in graveyards, Woite takes advantage of a loophole in the law so his customers can take their loved ones home in an urn.

“Earth mixed with ashes, there’s no law about that in Germany,” Woite explained. “We bury over there and bring back the earth mixed with ashes, and that’s what I hand over to the people.”

Woite has been heavily criticized by competitors for his Czech business. They say he’s irreverent, and they call the journeys to the Czech Republic “corpse tourism.” But that hasn’t stopped the undertaker. He’s planning an organized bus trip to the Czech Republic in April so customers can see for themselves where they or their loved ones may one day be cremated.

Here is the full story. Thanks to Michael Ward for the pointer.

The optimal gas needle

I learned yesterday that my gas needle is broken. It moves rather quickly to three-quarters of a tank, but is very sticky once it gets to half a tank. It used to be very sticky when it started on full. I could drive for two hours and it would remain on full the entire time.

I started wondering (actually I’ve been wondering this for years now) how an optimal gas needle should be structured. Assume that if a buyer has a bad experience with a car, such as running out of gas, he blames the car manufacturer with some probability. You might then expect that a car needle will stand on “Empty” long before the tank is empty. The needle makes you prematurely fearful and you are less likely to run out of gas.

You also might expect that the needle will be sticky at the top end of the register. Why?

When you fill your tank with gas, you have the clearest idea of exactly how much is in the tank. You are most likely to use observations from that point to gauge the fuel efficiency of the car. All other observations will be noisier. So the automaker wants to make a good impression about fuel efficiency right off the bat. This doesn’t require driver irrationality, only that you measure fuel efficiency with some imperfection. You’re never sure if the car gets great mileage or if the needle is just biased. But you attach some probability to the former. Economists call this a “signal extraction” problem. You suspect the needle is biased but you never know quite how much. (The technically-minded will note that once you introduce these information asymmetries, the assumption of rational expectations no longer rules out all kinds of errors; I first learned this from reading Joe Stiglitz.)

Furthermore some people refill their gas tank well before it gets to the bottom; they are just nervous nellies. These people will rarely observe the needle when it is on its path of swiftest descent. They observe how much they pay at the pump, but of course gas prices change all the time. They too will face a signal extraction problem and may overestimate the fuel efficiency of their car.

Some people will see through this entire business. But for them it doesn’t matter how the needle is structured. So a “sticky at the top” needle is most likely to induce a repeat purchase of the same kind of car.

Is this good? It may slightly limit competition in the car market. People stick with a brand because they think it offers better gas efficiency, when in fact it doesn’t. On the other hand, the practice makes the buyer feel good about his purchase. People think they bought a car with good mileage. The nervous nellies can rest easy. And the more irresponsible types are less likely to run out of gas.

So don’t forget the subtitle of this blog: Small ideas for a much better world.

Addendum: Of course as in most game theory you can spin alternate stories. Does this tempt you to switch disciplines? Just read Thomas Nagel’s recent essay on why there is something rather than nothing. Nagel is extraordinarily bright, but this is enough to bring you back into the fold.

Cognitive Liberty

Freedom of thought is the most fundamental right. Fortunately, it has been nearly impossible to invade the mind. New technologies, however, do threaten freedom of thought, raising many difficult problems. Should children diagnosed with ADHD who refuse to take Ritalin be refused an education? Should a mentally-ill person be drugged so that they can stand trial? Is hypersonic advertising an invasion of mental privacy?

Here’s an interesting interview on these and related issues with Richard Glen Boire co-founder of the Center for Cognitive Liberty and Ethics.

Index funds, still the way to go

If the market is efficient then without an information advantage (non-public information) you can’t expect to beat the market and thus index funds are a good way for the average investor to invest. Behavioral finance has put some dents in efficient markets theory but just because a market is inefficient that doesn’t mean that beating the market is easy. Even if you knew that firm X was way overvalued, for example, shorting the stock would expose you to great risk – the price could become irrationally higher before the bubble bursts, unexpected events could increase the fundamental value to match the bubble, your capital could run out before the price drops and, of course, you could be wrong.

When you hear the term inefficient market don’t think $500 bills lying on the sidewalk, think $500 bills swirling around you in a vortex of wind…at night. Inefficiency is out there but it’s hard to find.

The bottom line remains that most professional money managers don’t beat the market. Here’s a recent reminder from James Glassman of this fact:

Charles Allmon points out that last year the poorly rated stocks of many research services outperformed their highly rated stocks. For example, Standard & Poor’s one-star stocks returned 57 percent while its five-star stocks returned 43 percent. Merrill Lynch’s sell-rated stocks returned 46 percent while its buy-rated stocks returned 30 percent. Schwab’s F-rated stocks returned 70 percent while its A-rated stocks returned 66 percent. The biggest discrepancy came with Value Line, whose 5-rated stocks (the 100 companies with, supposedly, the worst prospects for the year ahead) returned an incredible 90 percent while the 1-rated stocks (the top prospects) returned 40 percent.

The latest hypothesis about sexual selection

Read here, to learn why many women prefer prominent cheekbones.

Radical Prescription

A recent Rand study of 25 large firms found that raising the co-pay for pharmaceutical claims by just $5 reduced yearly drug costs per worker by $163.*

An interesting piece in the WSJ (“A Radical Prescription,” May 20, 04, R3) suggests that this logic does not always hold. Higher co-pays can cause consumers to cut back on prophylactic and maintenance medicines. Pitney Bowes, for example, found that high-prices caused their diabetic and asthmatic workers to take their medicines irregularly resulting in sudden and expensive attacks. So Pitney Bowes took a counter-intuitive strategy – to save money they would pay for more of their workers prescriptions.

On the new plan workers began to switch to more expensive but more convenient and thus easier to maintain drugs and within a year the company was saving money.

the company was paying more for maintenance medications… [but] it was spending significantly less on rescue medicines…

[S]ignficant saving has come from fewer emergency room visits, which dropped 35% among diabetes patients and 20% among asthma patients…there were also fewer hospital admissions and doctor’s office visits.

The strategy won’t work for all drugs but it shows how much care must be taken in devising optimal insurance plans.

* Originally, I had said this implies a cost to benefit ratio in excess of 30 (163/5). Robert Ayers pointed out, however, that the co-pay is per drug while the savings are per year. Thus the cost-benefit ratio must be lower than 30. The original source doesn’t provide the data to calculate it exactly, however. Thanks Robert!

Indian voters reject high-tech

India appears to take a turn for the worse:

The government in Andhra Pradesh state, headed by the coalition’s second-largest member and a leading proponent of India’s technology revolution, was routed by the Congress party, which is also the main opposition on the national stage.

Besides signalling that high-tech prowess had not impressed the millions of rural poor, the result suggested the national election could end in a hung parliament and likely political turmoil as parties searched for new allies.

Votes from the marathon national election will be counted on Thursday but financial markets have already tumbled on fears that India’s crucial economic reforms could be delayed if a weak government comes to power.

Here is the full story.

Let us not forget that India remains a badly messed-up economy. I found the following passage, from William Lewis’s The Power of Productivity, illuminating:

…India has a special problem. It is not clear who owns land in India. Over 90 percent of land titles are unclear…Unclear land titles most affect industries which use a lot of land. These industries are housing construction and retailing. The result is that there is huge demand for the very little land with clear titles. Not surprisingly, the ratio of land costs to per capita income in New Delhi and Bombay is ten times that ratio in the other major cities of Asia…Also not surprisingly, India has very few supermarkets and large-scale single-family housing developments.

But it gets worse: Stamp taxes on land sales run at least ten percent. Furthermore you are often expected to pay real estate taxes, even if you will never be granted title to the actual land. It is said that the money is accepted “without prejudice.” Here is a short article on how to make things better.

Question of the day

Click here, from the ever-effervescent Jane Galt.

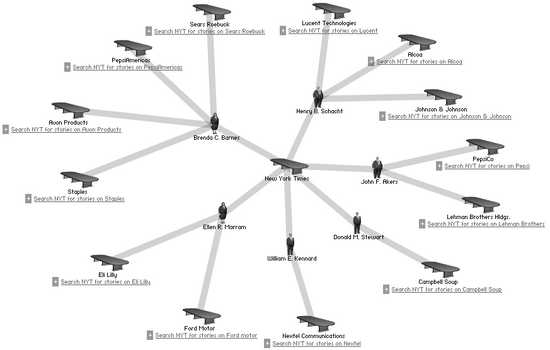

Map the Power Elite

They Rule is a very cool website that uses flash player as a front-end to a database on corporate boards. Find out who is on the board of any of the largest publicly held corporations, choose two firms and find the connections between their boards (ala six degrees of separation), map the power-elites. The map below (click to expand) gives an idea of what the site is all about.

The author, Josh On, is an odd-mix of old-style lefty and cutting edge technologist. When he’s not putting together websites like this what does he do?

Twice a week I stand outside on a street corner and try to engage strangers in conversations about politics. This would be much harder without a copy of Socialist Worker in my hand.

Hat tip to Boing Boing Blog.

Will Google’s Dutch auction go well?

It sounds great: cut out the investment banking fees and just offer a straight Dutch auction on the stock. After all, aren’t auctions the perfect market institution?

Co-blogger Alex thinks that the investment banks have had a comeuppance due for a long time; he may well be right.

Under standard practice, the underwriters give underpriced shares to favored investors and executives. The value of those shares rises on opening day. The insiders are happy but the company has left money on the table. In extreme and indeed pathological cases the discount can be as high as eighty percent. So why have companies tolerated this practice for so long?

Under one apologetic view, the kickbacks, underpriced shares, and payola are necessary. Someone has to produce reputation for the stock. The investment bank is paid to do this. The underwriter, in turn, gives insiders good deals to get them to boost the stock. If you own some shares you will do your best to talk up the issue. The efficient markets hypothesis? Well, it may be true at the margin, but how do we get to this margin in the first place?

I heard another point from one industry insider. Investors feel better about a stock if it goes up on day one. For the long-run good of the stock, it is important to have a price rise in the beginning. If investors sour on the stock in its early days, it may never recover its reputation.

Other skeptics wonder how the results of the auction can be predicted? How many people will show up with bids? What if we gave an auction and nobody came? Other worriers fear the temptation for untutored investors to bid too high at first, pushing the shares to unsustainable levels. After all, no single investor will have the final price much with his or her bid.

There is yet another fear. If the auction is fair, the stock will sell at roughly the same price on day one and day two. So if there is some uncertainty surrounding the initial auction, why not just hold off your buying until day two? But then how do liquid markets get established in the first place? How can you get concentrated buying interest on day one, but without violating either fairness or the efficiency of markets?

The resolution: …will have to wait for the facts and thus the actual auction. But my suspicion is the following. Some percentage of the original underpricing, but by no means all, is in fact a legitimate return to the investment banks. I thus worry that Google will not see strong demand on day one. On top of that, there is a puzzle. Unless you think all of the initial share underpricing is an legitimate fee for services rendered, why have markets tolerated this practice for so long?

By the way, David Levy informs me that used book dealer ALibris will try a share auction as well. For whatever reasons, except for Google, only small companies have shown an interest in these alternative institutions. France uses such auctions more commonly; it seems that the first-day price run-up is smaller but still present. On one hand, these other examples suggest that the auctions are a viable institution. On the other hand, it makes you wonder why the practice is not used more often.

Addendum: Here is a very good piece on the auction of Salon.com stock.

Opening at Cannes

The Cannes film festival starts this week, despite a threatened labor disruption. Yesterday I learned that the term Asia Extreme, the hot style in world cinema right now, has been copyrighted. “Asia Extreme” movies view John Woo as a quaint forefather and go much further in terms of throwing the book away. Are you interested? I’ll recommend Battle Royale for horrific Hobbesian violence, and The Audition for shocking sexual drama. Both are Japanese, and neither is for the fainthearted. But if you feel jaded by most movies, a bit bored, and are looking for something conceptual, this is definitely the next step.

The most popular names

For 2003, the most popular baby names were Jacob and Emily, here is the whole list, including a comparison with 1903. Here is an earlier post by Alex (the link is now fixed), on how names affect our earning potential.