Results for “duflo” 69 found

Sunday assorted links

1. “As of Wednesday, women and men in Panama are under different quarantine schedules.”

2. Banerjee and Duflo give their take.

3. On the decline of “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” (I myself prefer “Cloudy,” among many other S&G songs.)

4. Does financial stress spur entrepreneurship?

5. “We find that firms that had more connections on the eve of the 1929 financial market crash have higher 10-year survival rates during the Great Depression. Consistent with a financing channel, we find that the results are particularly strong for small firms, private firms, cash-poor firms, and firms located in counties with high bank suspension rates during the crisis. Moreover, connections to cash-rich firms are stronger predictors of survival, overall and among financially constrained firms.” Link here.

6. Is classical music becoming culturally more central under the lockdown?

7. 1957 flu memories, that was then this is now.

8. Roger Congleton model of the pandemic, the link downloads it rather than opening it up.

9. Maybe shaky as evidence, but this paper argues that thinking about coronavirus makes people more right-wing.

10. New site/model on estimating the number of infections.

The Advance Market Commitment

NBER: Ten years ago, donors committed $1.5 billion to a pilot Advance Market Commitment (AMC) to help purchase pneumococcal vaccine for low-income countries. The AMC aimed to encourage the development of such vaccines, ensure distribution to children in low-income countries, and pilot the AMC mechanism for possible future use. Three vaccines have been developed and more than 150 million children immunized, saving an estimated 700,000 lives. This paper reviews the economic logic behind AMCs, the experience with the pilot, and key issues for future AMCs.

That’s Kremer, Levin and Snyder. Definitely deserving of a Nobel and kudos to Bill and Melinda Gates for being early and major supporters.

Poor Economics

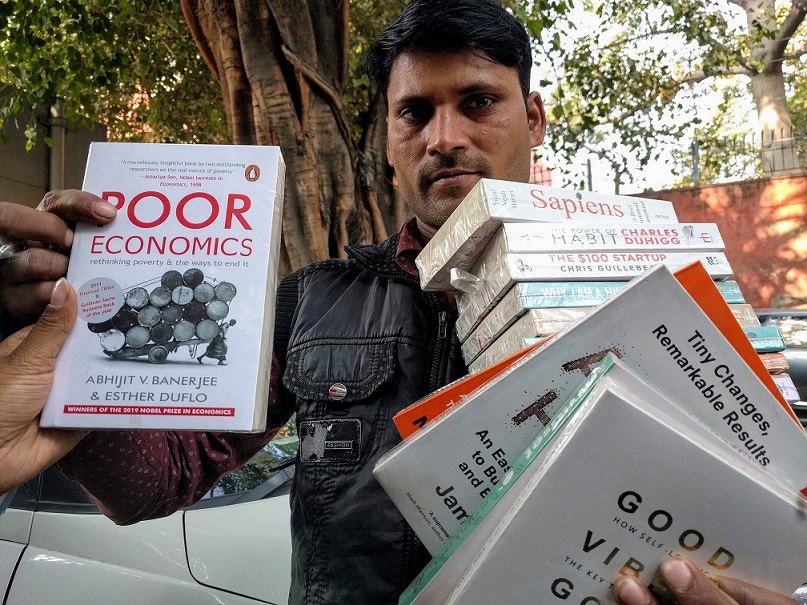

In Delhi, street hawkers will sell food, flowers, and balloons to cars paused at an intersection and, sadly, small children will dance for alms. My favorites are the book hawkers. I suspect Banerjee and Duflo would approve of my choice of both title and seller. Good price also.

Is it harder to become a top economist?

Mathis Lohaus writes to me:

Thanks for doing the Conversations. I greatly enjoyed Acemoglu, Duflo, and Banerjee in short succession after the Christmas break. Your question about “top-5 journals” and the bits about graduate training reminded of something I’ve had on my mind for a while now:

For the average PhD student, how hard is it to become a tenured economist — compared to 10, 20, 30, 40 … years ago? (And how about someone in the top 10% of talent/grit?)

Publication requirements have clearly become tougher in absolute terms. But how difficult is it to write a few “very good” papers in the first place? On twitter, people will sometimes say things like “oh, it must have been nice to get tenure back in 1997 based on 1 top article, which in turn was based on a simple regression with n = 60”. I wonder if that criticism is fair, because I imagine the learning curve for quantitative methods must have been challenging. And what about the formal models etc.? Surely those were always hard. (I vaguely remember a photo showing difficult comp exam questions…)

More broadly, early career scholars now have tons of data and inspiring research at their fingertips all the time. Also, nepotism and discrimination might be less powerful than in earlier decades…? On the other hand, you have to take into account that many more PhDs are awarded than ever before. I suspect that alone is a huge factor, but perhaps less acute if we focus only on people who “really, really want to stay in academia”.

A different way to ask the question: When would have been the best point in time to try to become an econ professor (in the USA)?

I would love to hear about your thoughts, and/or input from MR readers.

I always enjoy questions that somewhat answer themselves. I would add these points:

1. The skills of networking and finding new data sets are increasingly important, all-important you might say, at least for those in the top tier of ability/effort.

2. Fundraising matters more too, because the project might cost a lot, RCTs being the extreme case here.

3. Managing your research team matters much more, and the average size of research team for influential work is much larger. Once upon a time, three authors on a paper was considered slightly weird (the claim was one of them virtually always did nothing), now four is quite normal and the background research support is much higher as well.

Recently I was speaking to someone on the job market, wondering if he should be an academic. I said: “In the old days you spent a higher percentage of your time doing economics. Nowadays, you spend a higher percentage of your time managing a research team doing economics. You hardly do economics at all. So if you are mainly going to be a manager, why not manage for the higher rather than the lower salary?”

That was tongue in cheek of course.

On the bright side, learning today through the internet is so much easier. For instance, I find YouTube a good way to learn/refresh on new ideas in econometrics, easier than just trying to crack the final published paper.

What else?

Most Popular Posts of 2019

Here are the top MR posts for 2019, as measured by landing pages. The most popular post was Tyler’s

1. How I practice at what I do

Alas, I don’t think that will help to create more Tylers. Coming in at number two was my post:

2. What is the Probability of a Nuclear War?

Other posts in the top five were 3. Pretty stunning data on dating from Tyler and my posts, 4. One of the Greatest Environmental Crimes of the 20th Century,and 5. The NYTimes is Woke.

My post on The Baumol Effect which introduced my new book Why are the Prices So Damned High (one of Mercatus’s most downloaded items ever) was number 6 and rounding out the top ten were a bunch from Tyler, including 7. Has anyone said this yet?, 8. What is wrong with social justice warriors?, 9. Reading and rabbit holes and my post Is Elon Musk Prepping for State Failure?.

Other big hits from me included

- Air Pollution Reduces IQ, a Lot (Mostly a Patrick Collison post)

- The Nobel Prize in Economic Science Goes to Banerjee, Duflo, and Kremer

- Bitcoin is Less Secure than Most People Think

- Active Learning Works But Students Don’t Like It

- Sex Differences in Personality are Large and Important

Tyler had some truly great posts in the last few days of 2019 including what I thought was the post of the year (and not just on MR!) Work on these things.

Also important were:

- “What will you do to stay weird?”

- Joker

- Amazon and Taxes a Simple Primer

- Best Non-fiction books of 2019.

Happy holidays everyone!

Sunday assorted links

1. Technological progress in rock climbing.

2. Technological progress in bowling alleys, which are making a comeback (Bloomberg).

3. Duflo and Banerjee on incentives and economic policy (NYT).

The O-Ring Model of Development

Michael Kremer’s Nobel prize (with Duflo and Banerjee) reminded me of his important paper The O-Ring Theory of Development. I also rewatched my video on this paper from Tyler’s and my online class, Development Economics. This was from our powerpoint and iPad days so there are no fancy graphics but the video holds up! Mostly because it’s a great model with lots of interesting implications not just for development but also for the structure of the US economy. See also Jason Collins on Garett Jones’s extension of the model.

Michael Kremer, Nobel laureate

To Alex’s excellent treatment I will add a short discussion of Kremer’s work on deworming (with co-authors, most of all Edward Miguel), here is one summary treatment:

Intestinal helminths—including hookworm, roundworm, whipworm, and schistosomiasis—infect more than one-quarter of the world’s population. Studies in which medical treatment is randomized at the individual level potentially doubly underestimate the benefits of treatment, missing externality benefits to the comparison group from reduced disease transmission, and therefore also underestimating benefits for the treatment group. We evaluate a Kenyan project in which school-based mass treatment with deworming drugs was randomly phased into schools, rather than to individuals, allowing estimation of overall program effects. The program reduced school absenteeism in treatment schools by one-quarter, and was far cheaper than alternative ways of boosting school participation. Deworming substantially improved health and school participation among untreated children in both treatment schools and neighboring schools, and these externalities are large enough to justify fully subsidizing treatment. Yet we do not find evidence that deworming improved academic test scores.

If you do not today have a worm, there is some chance you have Michael Kremer to thank!

With Blanchard, Kremer also has an excellent and these days somewhat neglected piece on central planning and complexity:

Under central planning, many firms relied on a single supplier for critical inputs. Transition has led to decentralized bargaining between suppliers and buyers. Under incomplete contracts or asymmetric information, bargaining may inefficiently break down, and if chains of production link many specialized producers, output will decline sharply. Mechanisms that mitigate these problems in the West, such as reputation, can only play a limited role in transition. The empirical evidence suggests that output has fallen farthest for the goods with the most complex production process, and that disorganization has been more important in the former Soviet Union than in Central Europe.

Kremer with co-authors also did excellent work on the benefits of school vouchers in Colombia. And here is Kremer’s work on teacher incentives — incentives matter! His early piece on wage inequality with Maskin, from 1996, was way ahead of its time. And don’t forget his piece on peer effects and alcohol use: many college students think the others are drinking more than in fact they are, and publicizing the lower actual level of drinking can diminish alcohol abuse problems. The Hajj has an impact on the views of its participants, and “… these results suggest that students become more empathetic with the social groups to which their roommates belong,.” link here.

And don’t forget his famous paper titled “Elephants.” Under some assumptions, the government should buy up a large stock of ivory tusks, and dump them on the market strategically, to ruin the returns of elephant speculators at just the right time. No one has ever worked through the issue before of how to stop speculation in such forbidden and undesirable commodities.

Michael Kremer has produced a truly amazing set of papers.

*Good Economics for Hard Times*

Yes, that is the new and forthcoming book by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, and it tells you what they really think about everything. Everything in mainstream economic policy debate, at least.

So far I have read only the first chapter, on migration, but I found it informative, highly readable, and (unlike many other popular books) subtle. I am excited to read the rest of the book, in the meantime here is one short excerpt:

Mahesh found these would-be [Nepali] migrants were in fact somewhat overoptimistic about their earnings prospects. Specifically, they overestimated their earning potential by around 25 percent, which could be for any number of reasons, including the possibility the recruiters who go to them with job offers lie to them. But the really big mistake they made was that they vastly overestimated the chance of dying while they were abroad. A typical candidate for migration thought that out of a thousand migrants, over a two-year stint, about ten would come back in a box. The reality is just 1.3.

Here is the table of contents:

1. MEGA: Make Economics Great Again

2. From the Mouth of the Shark

3. The Pains from Trade

4. Likes, Wants and Needs

5. The End of Growth?

6. In Hot Water

7. Player Piano

8. Legit.gov

9. Cash and Care

Due out November 12, you can pre-order here.

Who should receive a cash transfer?, or the paradox of micro-credit

Let’s say you send regular money to a poorer individual in another country. You might wonder what are the possible rates of return on those funds, and furthermore does that analysis shape to whom you should give the money?

I don’t quite believe the argument I am about to write out, but I can’t yet find the flaw in it either.

Let’s say you find an individual borrowing micro-credit. It is well-known that rates of interest on these loans often run between 50 to 100 percent, annualized, and furthermore many individuals/families dip into these markets frequently. Furthermore, very high quality RCTs by Duflo et.al. and Dean Karlan show that micro-credit is not on average harming the families who borrow.

That implies these economies — at least in some their corners — have investments and/or liquidity deployments worth at least fifty percent per annum. For simplicity, I will use an estimate of fifty percent.

Go to a borrowing individual and give him/her some money for free. If micro-credit is no longer necessary, you have given that individual a high return. If it was a cash-free loan, the return to that person would be fifty percent. By simply giving the money away, it would seem the rate of return would be at least 2x that, or at least one hundred percent. That is pretty good too. Of course that individual might stay in the micro-credit market (post-gift), but that implies there are still worthwhile additional uses for the marginal liquidity. And we’ve already seen that micro-credit does not usually harm those who use it.

So you’ve generated returns of one hundred percent or more with your cash transfer. This does not require heroic acts of entrepreneurship, merely that the individual was previously a responsible user of micro-credit.

It also requires that these individuals be reasonably conscientious, and do not simply squander their new-found wealth.

But the core recipe is to give to conscientious current borrowers, for very high rates of return.

What is wrong with this argument?

Who will win the Nobel Prize in economics this year?

I’ve never once gotten it right, at least not for exact timing, so my apologies to anyone I pick (sorry Bill Baumol!). Nonetheless this year I am in for Esther Duflo and Abihijit Banerjee, possibly with Michael Kremer, for randomized control trials in development economics.

Maybe they are too young, as Tim Harford points out, so my back-up pick remains an environmental prize for Bill Nordhaus, Partha Dasgupta, and Marty Weitzman.

What do you all predict?

Tuesday assorted links

1. How much parsimony is there in behavioral economics?

2. The last time a foreign power successfully intervened in an American presidential election.

3. Beatrice Cherrier is a new and noteworthy figure in the economics blogosphere.

4. Arnold Kling on economics and culture.

5. Scalpers with Trump event tickets are getting burned. In fairness, it should be noted that the returns to scalpers are not distributed normally across events.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Esther Duflo’s Ely lecture, “The economist as plumber.”

2. Disappearing markets in everything: the last disco ball maker (there is noisy sound at the link). And how bad is authoritarianism really? And David Brooks on Bannon vs. Trump, I am always happy to see actual analysis of the Trump administration.

3. The best economic history works in the last decade? (pt. I)

4. AI now wins in heads-up, no-limit Texas hold’em poker. That is a game of asymmetric information.

5. The books some Australian guy is looking forward to.

6. If they had served this up as parody, I would have thought it too exaggerated. Did Darwinian processes really produce this? I guess so.

7. Long Piketty blog post on productivity in Germany and France. It does seem he is now blogging in English (and French) for Le Monde.

Who will win the Nobel Prize in Economics this coming Monday?

I’ve never once nailed the timing, but I have two predictions.

The first is William Baumol, who is I believe ninety-four years old. His cost-disease hypothesis is very important for understanding the productivity slowdown, see this recent empirical update. Oddly, the hypothesis is most likely false for the sector where Baumol pushed it hardest — music and the arts.

Baumol has many other contributions, but the next most significant is probably his theory of contestable markets, plus his writings on entrepreneurship.

The other option is a joint prize for environmental economics, perhaps to William Nordhaus, Partha Dasgupta, and Martin Weitzman. A prize in that direction is long overdue.

The “Web of Science” predicts Lazear, Blanchard, or Marc Melitz, based on citation counts. Other reasonable possibilities include Robert Barro, Paul Romer, Banerjee and Duflo and Kremer (joint?), David Hendry, Diamond and Dybvig, and Bernanke, Woodford, and Svensson, arguably joint. I still am of the opinion that Martin Feldstein is deserving, don’t forget he did empirical public finance, was a pioneer in health care economics, and built the NBER. For a dark horse pick, how about Joseph Newhouse (RCTs and the Rand health care study)?

There are other options — what is your prediction?

Nobel Prize poll results

The MRUniversity booth at the AEA meetings polled economists on a walk-by basis, as to who should win the next Nobel Prize. The top five on the list were:

Robert Barro

Paul Romer

Esther Duflo

Partha Dasgupta

William Nordhaus

Do check out the whole list at the link. Yoram Bauman was perhaps the dark horse candidate.