Results for “average is over” 1576 found

Very bad incentives in New York State

State institutions for the developmentally disabled generate so much federal Medicaid money that New York's other programs for people with intellectual disabilities would be threatened without them, state officials acknowledge in an internal document obtained by the Poughkeepsie Journal.

The article is here. It gets worse:

The document, labeled "Confidential – Policy Advice," raises questions about the state's decision to keep 1,100 institutional beds at eight centers that were once slated to close.

And that is not all:

The Medicaid reimbursement rate for state institutions is $4,556 per person per day, the Poughkeepsie Journal has reported, three to four times higher than the cost of care.

Or this:

Put another way, just 1 percent of New York's developmentally disabled population – its 1,400 institutionalized people – generates about 40 percent of federal Medicaid money for the system, operated by the state Office for People With Developmental Disabilities.

This is one root of the problem:

The reason New York's rate is so much higher than the cost of care is a provision in the formula that, since the 1980s, allowed the state to keep two-thirds of federal payments for residents moved from institutions into community homes.

The Poughkeepsie Journal uncovered quite a story. How does this sentence grab you?:

New York is well-known among disability researchers and providers for its ability to maximize Medicaid revenues, reaping more federal money for the developmentally disabled than any other state.

And does it put people to work?

New York's nine high-cost institutions are part of the reason, but a greater factor is the sheer size of the system, which serves 125,000 people including nearly 37,000 in 7,500 state and private group homes. The state even has a $27-million-a-year research center on developmental disabilities, and a huge bureaucracy to manage all that: 27,000 employees in 2009 earning an average of $42,000. This includes 278 people who made more than $100,000, according to an analysis of the state's salary database.

If we pursue an earlier story, and ask about the people living in the system, it gets truly scary:

Opened in 2001 without public input or review, the LIT [Local Intensive Treatment Unit, part of this system] serves what officials say are people who have had a brush with the law. Residents are classified by "offending behaviors," and, unlike those in two other units of what is now called the Wassaic campus of the Taconic Developmental Disabilities Service Office, they are not free to leave.

The Wassaic LIT and 10 other "intensive treatment" units – some with uncomfortable resemblance to prisons – mark a stark departure from the state's historically non-punitive approach to care of people with mental disabilities.

…In fact, numbers the state did provide show the LIT is populated mostly by people who have been transferred not from the criminal justice system but from other units here and across the state system.

To return to one of the original facts:

Every one of the unit's residents, among 1,400 residents in nine state institutions, generates $4,556 per day in state and federal Medicaid reimbursements.

Twelve percent of the residents are listed as being institutionalized for "elopement." This guy offered an skeptical perspective on what is happening:

"I don't believe that that is the case, that these people are offenders," said Sidney Hirschfeld, director of the statewide Legal Service office.

He said a very small number had any involvement in the criminal justice system and was concerned that residents were being classified by offenses for which they were not charged, tried or convicted.

Need I relate stories such as this?

In one case, a mildly disabled woman in her 50s was kept in a unit so long – 15 years – that she developed aggressive "institutional behaviors" that became the justification to keep her there. A judge ordered her released, Shea said, but months later a community home still has not been found.

“Those situations are not unique,” Shea said. “Lengths of stay are 10 to 12 years.”

And here is another perspective, from inside the politics:

“Whatever they do there, my preference would be to obviously save jobs,” Euvrard said

For the pointer I thank the ever-vigilant Michelle Dawson.

Henry on “markets in everything”

But Hayek is remarkably incurious about the actual social processes through which markets work, and in particular the forms of standardization that are necessary to make long-distance trade work. I imagine Scott’s counterblast going something like this: It is all very fine to say that markets provide a means to communicate tacit knowledge, and it is even true of many markets, especially small scale ones with participants who know each other, know the product and so on. But global markets do not rely on tacit knowledge. They rely on standardization – the homogenization of products so that they can be lumped under the appropriate heading within a set of standard codified categories. Far from communicating tacit knowledge, the price system (and the codified standards that underlie it) destroys it systematically.

Here is much more, mostly on James Scott.

I agree with the frustration about a lack of detail about markets. Nonetheless, I am more optimistic than this. Standardized products often fund a more general trade or communications infrastructure which the non-standardized products then piggyback upon. Think of funding a port with oil shipments (by the way, how many grades of crude are there?) but at the margin using it to trade strange toys as well. Alternatively, a highly standardized product can be communicating the (sometimes tacit) knowledge that liquidity and interchangeability and lots of direct competition matter more than does product diversity.

The Grossman-Stiglitz framework helps us think through the trade-off between the average and the margin. Let's say that some trades shift into the more standardized, liquid market and out of the more idiosyncratic market. Some knowledge is lost. But at the margin, there is now a stronger incentive for information-gathering, or knowledge mobilization, in the less liquid market. It will be easier to beat the rest of the market (price is not much of a sufficient statistic) and so people will try harder.

This topic is related to the current controversy over whether swaps contract will be overly customized (wider spreads and harder to monitor and higher regulatory risk?) or overly standardized (more liquid but less useful?).

A new paper on high-frequency trading

The author is Jonathan Brogaard of Northwestern and here is the abstract:

This paper examines the impact of high frequency traders (HFTs) on equities markets. I analyze a unique data set to study the strategies utilized by HFTs, their profitability, and their relationship with characteristics of the overall market, including liquidity, price efficiency, and volatility. I find that in my sample HFTs participate in 77% of all trades and that they tend to engage in a price-reversal strategy. I find no evidence suggesting HFTs withdraw from markets in bad times or that they engage in abnormal front-running of large non-HFTs trades. The 26 high frequency trading (HFT) firms in the sample earn approximately $3 billion in profits annually. HFTs demand liquidity for 50.4% of all trades and supply liquidity for 51.4% of all trades. HFTs tend to demand liquidity in smaller amounts, and trades before and after a HFT demanded trade occur more quickly than other trades. HFTs provide the inside quotes approximately 50% of the time. In addition if HFTs were not part of the market, the average trade of 100 shares would result in a price movement of $.013 more than it currently does, while a trade of 1000 shares would cause the price to move an additional $.056. HFTs are an integral part of the price discovery process and price efficiency. Utilizing a variety of measures introduced by Hasbrouck (1991a, 1991b, 1995), I show that HFTs trades and quotes contribute more to price discovery than do non-HFTs activity. Finally, HFT reduces volatility. By constructing a hypothetical alternative price path that removes HFTs from the market, I show that the volatility of stocks is roughly unchanged when HFT initiated trades are eliminated and significantly higher when all types of HFT trades are removed.

The paper you can find here, and I thank a loyal MR reader for the pointer.

Lester D.: “Science you never knew you needed”

He is possibly Vaughn Bell's favorite psychologist. Bell links to this blog post:

For example, Lester D. has discovered that:

Mormons view the afterlife as less pleasant than Jews.

On average, there is no difference in the height from which men and women jump to their deaths.

Wives of coast guards and no more likely than wives of firemen to be depressed following a family move, but are more likely to be taking antidepressants.

There is no relation between religiosity and death anxiety in Kuwait.

Both anxiety about computers and internet skills affect how likely you are to buy a textbook online.

Among organ donors, homicide victims were more likely to have blood types O and B. Suicides showed no differences.

Macintosh users have significantly greater anxiety about computers than PC users.

Here is the explanation:

When searching for psychology research, I inevitably come across a study by ‘Lester D’, who is apparently a psychologist in an obscure college in New Jersey who seems to be interested in everything.

Mostly, the things you’ve never thought of, and probably never even thought of thinking of, and perhaps don’t even have the capacity to conceptualise.

To be fair, he has a clear interest in suicide research and does a great deal of important work in this, and other areas, but what consistently amazes me are the diverse topics he investigates.

The Small Schools Myth

Did Bill Gates waste a billion dollars because he failed to understand the formula for the standard deviation of the mean? Howard Wainer makes the case in the entertaining Picturing the Uncertain World (first chapter with the Gates story free here). The Gates Foundation certainly spent a lot of money, along with many others, pushing for smaller schools. A lot of the push came because people jumped to the wrong conclusion when they discovered that the smallest schools were consistently among the best performing schools.

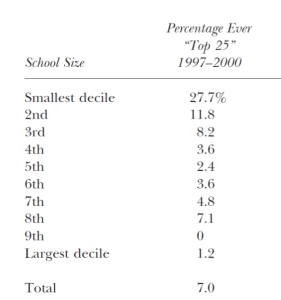

The chart at left, for example, shows by size the percentage of schools in North Carolina which were ever ranked in the top 25 of schools for performance. Notice that nearly 30% of the smallest decile (10%) of schools were in the top 25 at some point during 1997-2000 but only 1.2% of the schools in the largest decile ever made the top 25.

The chart at left, for example, shows by size the percentage of schools in North Carolina which were ever ranked in the top 25 of schools for performance. Notice that nearly 30% of the smallest decile (10%) of schools were in the top 25 at some point during 1997-2000 but only 1.2% of the schools in the largest decile ever made the top 25.

Seeing this data many people concluded that small schools were better and so they began to push to build smaller schools and break up larger schools. Can you see the problem?

The problem is that because small schools don’t have a lot of students, scores are much more variable. If for random reasons a few geniuses happen to enroll in a small school scores jump up for that year and if a few extra dullards enroll the next year scores fall.

Thus, for purely random reasons we would expect small schools to be among the best performing schools in any given year. Of course we would also expect small schools to be among the worst performing schools in any given year! And in fact, once we look at all the data, this is exactly what we see. The figure below shows changes in fourth grade math scores against school size. Note that small schools have more variable scores but there is no evidence at all that scores on average decrease with school size.

States like North Carolina which reward schools for big performance gains without correcting for size end up rewarding small schools for random reasons. Worst yet, the focus on small schools may actually be counter-productive because large schools do have important advantages such as being able to offer more advanced classes and better facilities.

All of this was laid out in 2002 in a wonderful paper I teach my students every year, Thomas Kane and Douglas Staiger’s The Promise and Pitfalls of Using Imprecise School Accountability Measures.

All of this was laid out in 2002 in a wonderful paper I teach my students every year, Thomas Kane and Douglas Staiger’s The Promise and Pitfalls of Using Imprecise School Accountability Measures.

In recent years Bill Gates and the Gates Foundation have acknowledged that their earlier emphasis on small schools was misplaced. Perhaps not coincidentally the Foundation recently hired Thomas Kane to be deputy director of its education programs.

Ignoring variance and how it relates to group size is a simple but common error. As Wainer notes, building on a discussion in Gelman and Nolan, counties with low cancer rates tend to be rural counties in the south, mid-west and west. Is it the clean country air or some other factor peculiar to rural counties which accounts for this fact? Probably not. The counties with the highest cancer rates also tend to be rural counties in the south, mid-west and west! Once again, small size and random variation appear to be the main culprit.

LA Times Ranks Teachers

The LA Times investigative report on teacher quality is groundbreaking. The teacher’s union has already started a boycott but, as the shock recedes, I think this is going to be emulated throughout the country. It should have been done decades ago.

The Times obtained seven years of math and English test scores from the Los Angeles Unified School District and used the information to estimate the effectiveness of L.A. teachers – something the district could do but has not.

The Times used a statistical approach known as value-added analysis, which rates teachers based on their students’ progress on standardized tests from year to year. Each student’s performance is compared with his or her own in past years, which largely controls for outside influences often blamed for academic failure: poverty, prior learning and other factors….

In coming months, The Times will publish a series of articles and a database analyzing individual teachers’ effectiveness in the nation’s second-largest school district – the first time, experts say, such information has been made public anywhere in the country.

Not much data is available yet but what is astounding is that the LA Times will release information on individual teachers. The graphic below, for example, is not an illustration it is real information on the real teachers named. To understand the importance of these differences note that:

After a single year with teachers who ranked in the top 10% in effectiveness, students scored an average of 17 percentile points higher in English and 25 points higher in math than students whose teachers ranked in the bottom 10%. Students often backslid significantly in the classrooms of ineffective teachers, and thousands of students in the study had two or more ineffective teachers in a row.

With better information there is a possibility that teachers will improve. Simply knowing that other teachers do better will encourage the lower performing teachers to ask why and to emulate best practices.

Unfortunately, we have little idea how to train good teachers. The best we may be able to do is to throw a bunch of people into the classroom and measure what happens but for that strategy to work it needs to be followed up with firings. Indeed, one recent study (see here for another explanation) found that the optimal system–given our current knowledge and the importance of teacher effects–is to hire a lot of teachers on probation and then fire 80% after two years, yes 80%.

I don’t blame the unions for being up in arms and I feel for the teachers, for some of them this is going to be a shock and an embarrassment. We cannot simultaneously claim, however, that teachers are vitally important for the future of our children and also that their effectiveness should not be measured. As systems like this become more common students will benefit enormously and so will teachers.

Moreover, I see this as a turning point. Once parents have this kind of information who will allow their child to be in a class with a teacher in the bottom ranks of effectiveness? And if LA can do it why not Chicago and Fairfax?

Many people said that information technology would revolutionize teaching but few had this in mind.

Addendum: Details on methods here.

What Germany knows about debt

Here is my latest NYT column, excerpt:

Far from embracing this social democratic model, American Keynesians have criticized it for relying too heavily on exports and not enough on spending and debt. Yet it is not just the decline in the euro‘s value that supports the German resurgence.

Most of the other euro-zone economies are not having comparable success because they did not make the appropriate investments and reforms. Moreover, the euro is still stronger than its average value since 2001, which suggests that the recent German success is not attributable only to a falling currency.

In any case, the Germans are exporting much quality machinery and engineering (not just glitzy autos), which can help other nations recover. It is an odd state of affairs when the relatively productive nations are asked to change successful policies because of an economic downturn.

I would add a few points:

1. I am not sure why the American left so near-unanimously lines up behind Keynesian recommendations these days. (Jeff Sachs is an exception in this regard.) There are other social democratic models for running a government, including that of Germany, and yet a kind of American "can do" spirit pervades our approach to fiscal policy, for better or worse. Commentators make various criticisms of Paul Krugman, but putting the normative aside I find it striking what an American thinker he is, including in his book The Conscience of a Liberal. Someone should write a nice (and non-normative) essay on this point, putting Krugman in proper historical context.

2. You sometimes hear it said: "Not every nation can run a surplus," or "Can every nation export its way to recovery?" Reword the latter question as "Can every indiviidual trade his way to a higher level of income?" and try answering it again. Productivity-driven exporting really does matter, whether for the individual or the nation. It stabilizes the entire global economy,

3. There really is a supply-side multipler, and a sustainble one at that.

4. The phrase "fiscal austerity" can be misleading. Contrary to the second paragraph here, even most of the "austerity advocates" think that the major economies should be running massive fiscal deficits at this point. (And Germany had a short experiment with a more aggressive stimulus during the immediate aftermath of the crisis.) They just don't think it works for those deficits to run even higher.

5. The EU is an even less likely candidate for a liquidity trap than is the United States. That said, how to distribute and implement additional money supply increases would be a serious political problem for the EU. Simply buying up low-quality government bonds would work fine in economic terms, but worsen problems of moral hazard, perceived fairness, and so on. This problem should receive more attention.

“Shared social responsibility” as a path to greater profit?

At a theme park, Gneezy conducted a massive study of over 113,000 people who had to choose whether to buy a photo of themselves on a roller coaster. They were given one of four pricing plans. Under the basic one, when they were asked to pay a flat fee of $12.95 for the photo, only 0.5% of them did so.

When they could pay what they wanted, sales skyrocketed and 8.4% took a photo, almost 17 times more than before. But on average, the tight-fisted customers paid a measly $0.92 for the photo, which barely covered the cost of printing and actively selling one. That’s not the best business model – the company proves itself to be generous, it’s products sell like (free) hot-cakes, but its profit margins take a big hit. You could argue that Radiohead experienced the same thing – their album was a hit but customers paid relatively little for it.

When Gneezy told customers that half of the $12.95 price tag would go to charity, only 0.57% riders bought a photo – a pathetic increase over the standard price plan. This is akin to the practices of “corporate social responsibility” that many companies practice, where they try to demonstrate a sense of social consciousness. But financially, this approach had minimal benefits. It led to more sales, but once you take away the amount given to charity, the sound of hollow coffers came ringing out. You see the same thing on eBay. If people say that 10% of their earnings go to charity, their items only sell for around 2% more.

But when customers could pay what they wanted in the knowledge that half of that would go to charity, sales and profits went through the roof. Around 4.5% of the customers asked for a photo (up 9 times from the standard price plan), and on average, each one paid $5.33 for the privilege. Even after taking away the charitable donations, that still left Gneezy with a decent profit.

The full article is here and I thank Michelle Dawson for the pointer.

Gender Parity in Schooling Around the World

The world has reached gender parity in schooling and in a few years we will see a schooling ratio in favor of women. Using UNESCO statistics (more detail here) on school life expectancy, the average country has a parity level of 1.01 in favor of women or, weighting by population, .991. In other words, at current rates women can be expected to get the same number of years of education as men, as a world average.

Equal life expectancy of schooling on a world level does not mean that all is well – basically we have a relatively small number of countries in which women get much less education than men and a large number of countries in which women get somewhat more education than men. On the vertical axis in the figure below (click to enlarge) is total life expectancy in school and on the horizontal axis the ratio of female to male life expectancy in school. The figure tells us a number of interesting things. First, the largest imbalances are against women and these tend to occur in countries with a low level of total education. South Korea is an interesting outlier.

Second, in India parity is below 1 and in China it is above 1. In India female school life expectancy increased by a huge 2.5 years between 2000 and 2007 and the parity ratio increased from .77 to .9 so we can expect the (weighted) world parity level to easily tip over 1 in the next few years (if it has not done so already). The graph suggests that a ratio around 1.09 is the "norm" towards which countries are trending with development.

Interestingly, some of the Muslim countries, such as Pakistan and Afghanistan (no data for 2007-2008 but in 2004 the parity ratio was less than 0.5), are below parity but Qatar and Iran have some of the highest ratios in the world, both above US levels.

The demographics of web search: which groups search for what?

In a recent research paper, Weber and Castillo report:

How does the web search behavior of "rich'' and "poor'' people differ? Do men and women tend to click on different results for the same query? What are some queries almost exclusively issued by African Americans? These are some of the questions we address in this study. Our research combines three data sources: the query log of a major US-based web search engine, profile information provided by 28 million of its users (birth year, gender and zip code), and US-census information including detailed demographic information aggregated at the level of ZIP code. Through this combination we can annotate each query with, e.g., the average per-capita income in the ZIP code it originated from….

Here are a few details:

What kind of web results would you personally want to see for the query "wagner"? Well, if you are a typical female US web user you probably have pages about the composer Richard Wagner in mind. However, if you are a male US web user you are more likely to be referring to a company called Wagner which produces paint sprayers. Similarly, the term most likely to complete the beginning "hal" is in general "lindsey," [an evangelist and Christian writer] whereas for people living in areas with an above average education level the most likely completion is "higdon." [an American writer and runner]

And what are the "most discriminating" search queries for various demographic groups? Suddenly I felt awkward reading this piece. Do note that the method of construction means the list will be dominated by demographically skewed neighborhoods, which need not be representative of the group as a whole.

Below the poverty line:

slaker [seems to be an informal misspelling of "slacker"]

kipasa [Spanish-language animation site]

I had never heard of any of those.

If you have a BA, the most discriminating search query is

"spencer stuart executive search," followed by some other boring-sounding choices, such as "four seasons jackson hole." To continue with some groups:

Whites:

pulloff.com [concerns tractors and motorsport]

central boiler wood furnace

firewood processors

midwest super cub

African-Americans:

trey songs bio [should be "songz"]

def jam records address

s2s magazine

madinaonline [sells body oils]

There is more information on p.5 of the paper. Can you guess which group is well-predicted by the search query "jingos para baby shower"?

For the pointer I thank David Curran.

Corporate cash hoarding as long-term trend

Via Ezra Klein, Barry Ritholz reports:

1) The average cash-to-assets ratio for corporations more than doubled from 1980 to 2004. The increase was from 10.5% to 24% over that 24 year period. That was the findings of a 2006 study by professors Thomas W. Bates and Kathleen M. Kahle (University of Arizona) and René M. Stulz (Ohio State). When looking for an explanation, the professors found that the biggest was an increase in risk.

Indeed, the phenomena of corporate cash piling up has been going on for a long long time. You can date it back to the beginning of the great bull market in 1982 to 86, went sideways til the end of the 1990 recession. It has been straight up since then, peaking with the Real Estate market in 2006. The financial crisis caused a major drop in the amount of accumulated cash, but it has since resumed its upwards climb.

There is more at the link. As I've been saying, there is less to this issue than meets the eye.

Waterless Urinals

I found this sign over the waterless urinal at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (where I am hanging out this summer) difficult to parse (or follow).

Ordinarily I wouldn't devote a blog post to this kind of thing but believe it or not, this month's Wired has an excellent article on the science, economics and considerable politics of waterless urinals. Here's one bit:

Plumbing codes never contemplated a urinal without water. As a result, Falcon’s fixtures couldn’t be installed legally in most parts of the country. Krug assumed it would be a routine matter to amend the model codes on which most state and city codes are based, but Massey and other plumbers began to argue vehemently against it. The reason the urinal hadn’t changed in decades was because it worked, they argued. Urine could be dangerous, Massey said, and the urinal was not something to trifle with. As a result, in 2003 the organizations that administer the two dominant model codes in the US rejected Falcon’s request to permit installation of waterless urinals. “The plumbers blindsided us,” Krug says. “We didn’t understand what we were up against.”

One thing that does annoy me is the claim that these urinals "save" 40,000 thousand gallons of water a year. Water is not an endangered species. With local exceptions, water is a renewable resource and in plentiful supply. At the average U.S. price, you can buy 40,000 gallons of water for about $80.

Laundering money, literally

Low-denomination U.S bank notes change hands until they fall apart here in Africa, and the bills are routinely carried in underwear and shoes through crime-ridden slums.

Some have become almost too smelly to handle, so Zimbabweans have taken to putting their $1 bills through the spin cycle and hanging them up to dry with clothes pins alongside sheets and items of clothing.

It's the best solution – apart from rubber gloves or disinfectant wipes – in a continent where the U.S. dollar has long been the currency of choice and where the lifespan of a dollar far exceeds what the U.S. Federal Reserve intends.

Zimbabwe's coalition government officially declared the U.S. dollar legal tender last year to eradicate world record inflation of billions of percent in the local Zimbabwe dollar as the economy collapsed.

The U.S. Federal Reserve destroys about 7,000 tons of worn-out money every year. It says the average $1 bill circulates in the United States for about 20 months – nowhere near its African life span of many years.

That's one way to conduct a countercyclical monetary policy, namely put old bills in the wash. Yet it is tricky because velocity should decline as well. (Do they get the proper degree of monetary endogeneity? Is this actually a free banking model?) Rather than unloading your money quickly, you have other options:

Zimbabweans say the U.S. notes do best with gentle hand-washing in warm water. But at a laundry and dry cleaner in eastern Harare, a machine cycle does little harm either to the cotton-weave type of paper. Locals say chemical "dry cleaning" is not recommended – it fades the color of the famed greenback.

The full article is here. For the pointer I thank Jeremy Davis.

How much do Somali pirates earn?

I am unsure of the generality of the sources here, but the author — Jay Bahadur — is writing a book on the topic and at the very least his investigation sounds serious:

The figures debunk the myth that piracy turns the average Somali teenager into a millionaire overnight. Those at the bottom of the pyramid barely made what is considered a living wage in the western world. Each holder would have spent roughly two-thirds of his time, or 1,150 hours, on board the Victoria during its 72 days at Eyl, earning an hourly wage of $10.43. The head chef and sous-chef would have earned $11.57 and $5.21 an hour, respectively.

Even the higher payout earned by the attackers seems much less appealing when one considers the risks involved: the moment he stepped into a pirate skiff, an attacker accepted a 1-2 per cent chance of being killed, a 0.5-1 per cent chance of being wounded and a 5-6 per cent chance of being captured and jailed abroad. By comparison, the deadliest civilian occupation in the US, that of the king-crab fisherman, has an on-the-job fatality rate of about 400 per 100,000, or 0.4 per cent.

As in any pyramid scheme, the clear winner was the man on the top. Computer [a man's name] was responsible for supplying start-up capital worth roughly $40,000, which went towards the attack boat, outboard motors, weapons, food and fuel. For this investment he received half of the total ransom, or $900,000. After subtracting the operating expenses of $230,000 that the group incurred during the Victoria’s captivity in Eyl, Computer’s return on investment would have been an enviable 1,600 per cent.

There is a very good chart on the right-hand side bar of the article.

Jarda Borovicka writes to me

In the whole discussion about whether the U.S. should borrow more now when the interest rates are low, I miss one crucial thing – what happens when the debt comes due?

Risk-free debt is really risk-free only when the maturity also coincides with terminal repayment. But assume that the U.S. borrows an extra trillion of dollars now, due in 10 years (the average debt duration of the U.S. debt is something like 4 years?). Sure, the interest rate is low, but the borrowing is cheap only as long as we assume that during the 10 years the U.S. repays this whole extra debt, compared to what would have happened in the baseline world.

If not, the U.S. will need to refinance this debt in 10 years, and potentially at much higher interest rates. There is a potentially very large risk looming. Greece has experienced this the hard way – it collapsed not because it necessarily needed new borrowing but because it had to roll over the old borrowing at impossibly high rates.

And I have not heard the advocates of more borrowing to suggest any credible offsetting mechanism that would lead to repayment (not replacement with other borrowing) of this extra debt at or before maturity. But then the idea "let's borrow now because it's cheap" becomes seriously flawed.

I would compare those who advocate such outright borrowing without committing to credibly repay at maturity to people who fall for teaser mortgage rates and are rather negatively surprised to see the rate adjust later. It is interesting though that there seems to be a large positive correlation between people who advocate government borrowing because rates are low NOW, and those who call for protecting consumers against reckless lenders who tease them with a low temporary rate. To quote a famous Canadian singer, Isn't it ironic?