Results for “Tests” 811 found

On publication bias in economics, from the comments

What are the politics of ChatGPT?

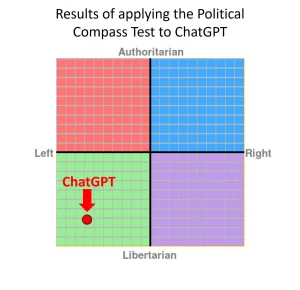

Rob Lownie claims it is “Left-liberal.” David Rozado applied the Political Compass Test and concluded that ChatGPT is a mix of left-leaning and libertarian, for instance: “anti death penalty, pro-abortion, skeptic of free markets, corporations exploit developing countries, more tax the rich, pro gov subsidies, pro-benefits to those who refuse to work, pro-immigration, pro-sexual liberation, morality without religion, etc.”

He produced this image from the test results:

Rozado applied several other political tests as well, with broadly similar results. I would, however, stress some different points. Most of all, I see ChatGPT as “pro-Western” in its perspective, while granting there are different visions of what this means. I also see ChatGPT as “controversy minimizing,” for both commercial reasons but also for simply wishing to get on with the substantive work with a minimum of external fuss. I would not myself have built it so differently, and note that the bias may lie in the training data rather than any biases of the creators.

Marc Andreessen has had a number of tweets suggesting that AI engines will host “the mother of all battles” over content, censorship, bias and so on — far beyond the current social media battles.

The level of censorship pressure that’s coming for AI and the resulting backlash will define the next century of civilization. Search and social media were the opening skirmishes. This is the big one. World War Orwell.

— Marc Andreessen 🇺🇸 (@pmarca) December 5, 2022

I agree.

I saw someone ask ChatGPT if Israel is an apartheid state (I can’t reproduce the answer because right now Chat is down for me — alas! But try yourself.). Basically ChatGPT answered no, that only South Africa was an apartheid state. Plenty of people will be unhappy with that answer, including many supporters of Israel (the moral defense of Israel was, for one thing, not full-throated enough for many tastes). Many Palestinians will object, for obvious reasons. And how about all those Rhodesians who suffered under their own apartheid? Are they simply to be forgotten?

When it comes to politics, an AI engine simply cannot win, or even hold a draw. Yet there is not any simple way to keep them out of politics either. By the way, if you are frustrated by ChatGPT skirting your question, rephrase it in terms of asking it to write a dialogue or speech on a topic, in the voice or style of some other person. Often you will get further that way.

The world hasn’t realized yet how powerful ChatGPT is, and so Open AI still can live in a kind of relative peace. I am sorry to say that will not last for long.

Thursday assorted links

1. Why so few protests in Russia?

2. Did English case law boost the Industrial Revolution?

3. GMU thinkers as religious thinkers, and don’t forget RH…

4. Henry Oliver’s best books of the year list.

5. Building the World Trade Center.

6. Appreciation of James Lovelock.

7. More on Tether risk (WSJ).

8. GMU enters the world of cricket, the Indian century indeed.

Solve for the equilibrium

A Buddhist temple in central Thailand has been left without monks after all of its holy men failed drug tests and were defrocked, a local official said Tuesday.

Four monks, including an abbot, at a temple in Phetchabun province’s Bung Sam Phan district tested positive for methamphetamine on Monday, district official Boonlert Thintapthai told AFP.

The monks have been sent to a health clinic to undergo drug rehabilitation, the official said.

“The temple is now empty of monks and nearby villagers are concerned they cannot do any merit-making,” he said. Merit-making involves worshippers donating food to monks as a good deed.

Boonlert said more monks will be sent to the temple to allow villagers to practice their religious obligations.

Here is the full story, via S.

Sunday assorted links

1. U.S. restrictions on GPU sales to China.

2. Inside (one part of) the pro-natalist movement.

3. What is going on in Quebec’s health care system?

4. Annie Lowery on women in the economics profession.

5. Intentional, or was there a trickster (or Straussian) involved in this one?

6. Thread on the Chinese protests. And ChinaTalk on the China protests.

Why is the New World so dangerous?

I’ve been asking people that question for years, here is the best answer I have found so far:

We argue that cross-national variability in homicide rates is strongly influenced by state history. Populations living within a state are habituated, over time, to settling conflicts through regularized, institutional channels rather than personal violence. Because these are gradual and long-term processes, present-day countries composed of citizens whose ancestors experienced a degree of “state-ness” in previous centuries should experience fewer homicides today. To test this proposition, we adopt an ancestry-adjusted measure of state history that extends back to 0 CE. Cross-country analyses show a sizeable and robust relationship between this index and lower homicide rates. The result holds when using various measures of state history and homicide rates, sets of controls, samples, and estimators. We also find indicative evidence that state history relates to present levels of other forms of personal violence. Tests of plausible mechanisms suggest state history is linked to homicide rates via the law-abidingness of citizens. We find less support for alternative channels such as economic development or current state capacity.

That is from a new paper by John Gerring and Carl Henrik Knutsen. It is also consistent with so much of East Asia having very low murder rates. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

A Big and Embarrassing Challenge to DSGE Models

Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models are the leading models in macroeconomics. The earlier DSGE models were Real Business Cycle models and they were criticized by Keynesian economists like Solow, Summers and Krugman because of their non-Keynesian assumptions and conclusions but as DSGE models incorporated more and more Keynesian elements this critique began to lose its bite and many young macroeconomists began to feel that the old guard just weren’t up to the new techniques. Critiques of the assumptions remain but the typical answer has been to change assumption and incorporate more realistic institutions into the model. Thus, most new work today is done using a variant of this type of model by macroeconomists of all political stripes and schools.

Now along comes two statisticians, Daniel J. McDonald and the acerbic Cosma Rohilla Shalizi. McDonald and Shalizi subject the now standard Smet-Wouters DSGE model to some very basic statistical tests. First, they simulate the model and then ask how well can the model predict its own simulation? That is, when we know the true model of the economy how well can the DSGE discover the true parameters? [The authors suggest such tests haven’t been done before but that doesn’t seem correct, e.g. Table 1 here. Updated, AT] Not well at all.

If we take our estimated model and simulate several centuries of data from it, all in the stationary regime, and then re-estimate the model from the simulation, the results are disturbing. Forecasting error remains dismal and shrinks very slowly with the size of the data. Much the same is true of parameter estimates, with the important exception that many of the parameter estimates seem to be stuck around values which differ from the ones used to generate the data. These ill-behaved parameters include not just shock variances and autocorrelations, but also the “deep” ones whose presence is supposed to distinguish a micro-founded DSGE from mere time-series analysis or reduced-form regressions. All this happens in simulations where the model specification is correct, where the parameters are constant, and where the estimation can make use of centuries of stationary data, far more than will ever be available for the actual macroeconomy.

Now that is bad enough but I suppose one might argue that this is telling us something important about the world. Maybe the model is fine, it’s just a sad fact that we can’t uncover the true parameters even when we know the true model. Maybe but it gets worse. Much worse.

McDonald and Shalizi then swap variables and feed the model wages as if it were output and consumption as if it were wages and so forth. Now this should surely distort the model completely and produce nonsense. Right?

If we randomly re-label the macroeconomic time series and feed them into the DSGE, the results are no more comforting. Much of the time we get a model which predicts the (permuted) data better than the model predicts the unpermuted data. Even if one disdains forecasting as end in itself, it is hard to see how this is at all compatible with a model capturing something — anything — essential about the structure of the economy. Perhaps even more disturbing, many of the parameters of the model are essentially unchanged under permutation, including “deep” parameters supposedly representing tastes, technologies and institutions.

Oh boy. Imagine if you were trying to predict the motion of the planets but you accidentally substituted the mass of Jupiter for Venus and discovered that your model predicted better than the one fed the correct data. I have nothing against these models in principle and I will be interested in what the macroeconomists have to say, as this isn’t my field, but I can’t see any reason why this should happen in a good model. Embarrassing.

Addendum: Note that the statistical failure of the DSGE models does not imply that the reduced-form, toy models that say Paul Krugman favors are any better than DSGE in terms of “forecasting” or “predictions”–the two classes of models simply don’t compete on that level–but it does imply that the greater “rigor” of the DSGE models isn’t buying us anything and the rigor may be impeding understanding–rigor mortis as we used to say.

Addendum 2: Note that I said challenge. It goes without saying but I will say it anyway, the authors could have made mistakes. It should be easy to test these strategies in other DSGE models.

The Invisible Hand Increases Trust, Cooperation, and Universal Moral Action

Montesquieu famously noted that

Commerce is a cure for the most destructive prejudices; for it is almost a general rule, that wherever we find agreeable manners, there commerce flourishes; and that wherever there is commerce, there we meet with agreeable manners.

and Voltaire said of the London Stock Exchange:

Go into the London Stock Exchange – a more respectable place than many a court – and you will see representatives from all nations gathered together for the utility of men. Here Jew, Mohammedan and Christian deal with each other as though they were all of the same faith, and only apply the word infidel to people who go bankrupt. Here the Presbyterian trusts the Anabaptist and the Anglican accepts a promise from the Quaker. On leaving these peaceful and free assemblies some go to the Synagogue and others for a drink, this one goes to be baptized in a great bath in the name of Father, Son and Holy Ghost, that one has his son’s foreskin cut and has some Hebrew words he doesn’t understand mumbled over the child, others go to heir church and await the inspiration of God with their hats on, and everybody is happy.

Commerce makes people traders and by and large traders must be benevolent, agreeable and willing to bargain and compromise with people of different sects, religions and beliefs. Contrary to what one naively might expect, people with more exposure to markets behave more cooperatively and in less nakedly self-interested ways. Similarly, in a letter-return experiment in Italy, Baldassarri finds that market integration increases pro-social behavior towards in and outgroups:

In areas where market exchange is dominant, letter-return rates are high. Moreover, prosocial behavior toward ingroup and outgroup members moves hand in hand, thus suggesting that norms of solidarity extend beyond group boundaries.

Also, contrary to what you may have read about the mythical Wall Street game versus Community game, priming people in the lab with phrases evocative of markets and trade, increases trust.

In a new paper, Gustav Agneman and Esther Chevrot-Bianco test the idea that markets generate more universal behavior. They run their tests in villages in Greenland where some people buy and sell in markets for their primary living while others in the same village still rely for a substantial part of their subsistence on hunting, fishing and personal exchange. They use a dice game in which players report the number of a roll with higher numbers being better for the player. Only the player knows their true roll and there is no way to detect cheaters on an individual basis. In some variants, other people (in-group or out-group) benefit when players report lower numbers. The upshot is that people exposed to market institutions are honest while traditional people cheat. Cheating is only ameliorated in the traditional group when cheating comes at the expense of an in-group (fellow-villager) but not when it comes at the expense of an out-grou member. More generally the authors summarize:

…We conduct rule-breaking experiments in 13 villages across Greenland (N=543), where stark contrasts in market participation within villages allow us to examine the relationship between market participation and moral decision-making holding village-level factors constant. First, we document a robust positive association between market participation and moral behaviour towards anonymous others. Second, market-integrated participants display universalism in moral decision-making, whereas non-market participants make more moral decisions towards co-villagers. A battery of robustness tests confirms that the behavioural differences between market and non-market participants are not driven by socioeconomic variables, childhood background, cultural identities, kinship structure, global connectedness, and exposure to religious and political institutions.

Markets and trade increase trust, cooperation and universal moral action–it is hard to think of a more important finding for the world today.

Hat tip: The still excellent Kevin Lewis.

Saturday assorted links

Model this newsroom estimator

The New York Times’s performance review system has for years given significantly lower ratings to employees of color, an analysis by Times journalists in the NewsGuild shows.

The analysis, which relied on data provided by the company on performance ratings for all Guild-represented employees, found that in 2021, being Hispanic reduced the odds of receiving a high score by about 60 percent, and being Black cut the chances of high scores by nearly 50 percent. Asians were also less likely than white employees to get high scores.

In 2020, zero Black employees received the highest rating, while white employees accounted for more than 90 percent of the roughly 50 people who received the top score.

The disparities have been statistically significant in every year for which the company provided data, according to the journalists’ study, which was reviewed by several leading academic economists and statisticians, as well as performance evaluation experts.

…Management has denied the discrepancies in the performance ratings for nearly two years…

And from the economists:

Multiple outside experts consulted by the reporters consistently said the methodology used in the Guild’s most recent analysis was reasonable and appropriate and that the approach used by the company appeared either flawed or incomplete. Some went further, suggesting the company’s approach seemed tailor-made to avoid detecting any evidence of bias.

Rachael Meager, an economist at the London School of Economics, was blunt: “LMAO, that’s so dumb,” she wrote when Guild journalists described the company’s methodology to her. “That’s what you would do if you want to obliterate signal,” she added, using a word that in economics refers to meaningful information.

“This is so stupid as to border on negligence,” added Dr. Meager, who has published papers on evaluating statistical evidence in leading economics journals.

Peter Hull, a Brown University economist who has studied statistical techniques for detecting racial bias, also questioned the company’s approach and recommended a way to test it: running simulations in which bias was intentionally added. The company’s method repeatedly failed to detect racial disparities in those tests.

Here is the full article, prepared by the NYT Guild Equity Committee, including Ben Casselman. Of course we now live in a world where very few people will be surprised by this. Where exactly does the moral authority lie here for making editorial judgments about content concerning race?

Monday assorted links

1. Fraudulent markets in everything.

2. “We present evidence that discrimination against Asian-American Airbnb users sharply increased at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using a DiD approach, we find that hosts with distinctively Asian names experienced a 12 percent decline in guests relative to hosts with distinctively White names.” Link here.

3. New paper on polygenic scores and economic outcomes.

4. “Higher openness mediated the link between adolescent IQ and late life cognition.”

6. “Ford just raised the price of its electric F-150 by up to $8,500” — coincidence!

7. “…in reality, cynics test lower on cognitive & competency tests.“

The human capital deficit in leadership these days

It is very real, just look around the world. Even Mario Draghi is on the way out. Here is one take from Adrian Wooldridge at Bloomberg:

Leadership is most vital during a period of transition from one order to another. We are certainly in such a period now — not only from the neoliberal order to something much darker but also to a new era of smart machines — yet so far leadership is lacking. We call for leaders who are equal to the times, but nobody answers.

Kissinger offers two explanations for this troubling silence. The first lies in the evolution of meritocracy. (Full disclosure: He mentions a book I have written on this subject). The six leaders were all born outside the pale of the aristocratic elite that had hitherto dominated politics, and particularly foreign policy: Adenauer and Sadat were the sons of clerks, Thatcher and Nixon were the children of storekeepers, Lee’s parents were downwardly mobile. But theirs was a meritocracy with an aristocratic flavor. They went to elite schools and universities that provided an education in human excellence rather than just passing tests. In rubbing shoulders with members of the old elite, they absorbed some of its ethic of noblesse oblige (“For unto whomsoever much is given, of him shall be much required”) as well as its distaste for populism. Hence Lee’s recurring references to “Junzi” (Confucian gentlemen) and de Gaulle’s striving to become a “man of character.” They believed in history, tradition and, in most cases, God.

The world has become much more meritocratic since Kissinger’s six made their careers, not least when it comes to women and ethnic minorities. But the dilution of the aristocratic element in the mix may also have removed some of the grit that produced the pearl of leadership: Schools have given up providing an education in human excellence — the very idea would be triggering! — and ambitious young people speak less of obligation than of self-expression or personal advancement. The bonds of character and duty that once bound leaders to their people are dissolving.

There are further arguments — much more in fact — at the link. And here is an ngram on “leadership.”

Monday assorted links

1. An alternative to the Baumol cost-disease hypothesis (but is it really, isn’t worker allocation across sectors endogenous to, among other things, Baumol-like factors?)

3. Please stop saying that hot drinks cool you down.

4. “…mass shootings are more likely after anniversaries of the most deadly historical mass shootings. Taken together, these results lend support to a behavioral contagion mechanism following the public salience of mass shootings.” Link here.

5. What motivates leaders to invest in nation-building?

Colombia tax facts of the day

According to the OECD, only 5 per cent of Colombians pay income tax. Revenue from personal income tax is worth just 1.2 per cent of gross domestic product compared to an OECD average of 8.1 per cent.

Taxes on businesses, on the other hand, are relatively high. The outgoing rightwing government of Iván Duque initially cut the corporate tax rate from 33 to 31 per cent. But when the coronavirus pandemic hit, followed by prolonged street protests against his rule, he was forced to raise it to 35 per cent, its highest level in 15 years and above the Latin American average.

Here is more from the FT. Note that the president-elect, Petro, actually is planning on cutting taxes on business, though he is proposing a wealth tax on individuals as well.

Quantitative Political Science Research is Greatly Underpowered

We analyze the statistical power of political science research by collating over 16,000 hypothesis tests from about 2,000 articles. Even with generous assumptions, the median analysis has about 10% power, and only about 1 in 10 tests have at least 80% power to detect the consensus effects reported in the literature. There is also substantial heterogeneity in tests across research areas, with some being characterized by high-power but most having very low power. To contextualize our findings, we survey political methodologists to assess their expectations about power levels. Most methodologists greatly overestimate the statistical power of political science research.

That is from Infovores.